Text | Whoops

"How much is the endurance of electric vehicles enough?" Discussions on this topic Chinese the Internet abound. The positive and negative are long and short, how to say it, and the axiom is said to be reasonable. But this latest time, the speaker's coffee position is a bit unusual.

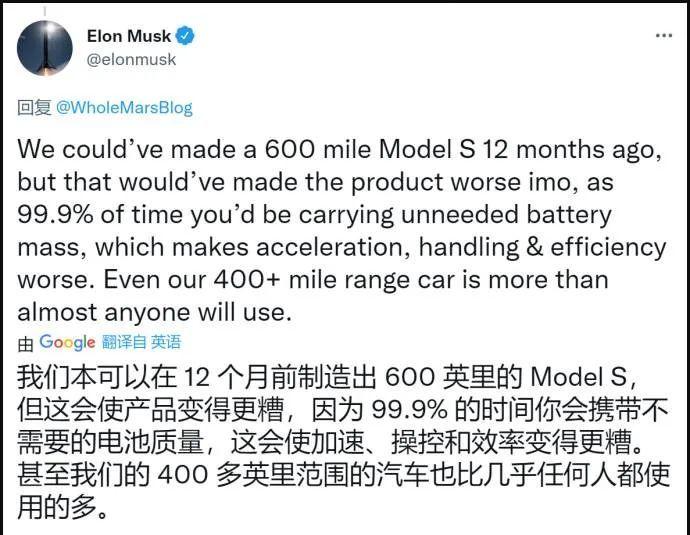

Musk stormed on a social networking site the other day: 1000km endurance? Oh, we were able to build it last year, but I don't think it's necessary, you can't use it.

This sentence has a Versailles-style harshness for the domestic car market that has just begun to appear sporadically with "1000km" electric vehicles. If it is Volkswagen and Toyota that speak, most of them will be buckled with titles such as "Traditional Car Companies Are Anxious to Eat Grapes and Say Grape Sour". However, Musk said that people have Teslas with long endurance and are famous in the industry, and no one can say what is not.

Large horse-style Versailles scene

The speaker title is heavy, but the reason is nothing new: because the battery is too heavy, too heavy will affect this and that, and now 400 miles (644km) are far enough...

Interestingly, Musk's argument is in response to a question from netizens: "Lucid was the first to make a 500-mile electric car, what do you think of Yuanfang?" And just last October, Lucid Motors' CTO just published a "violent square": electric vehicle endurance? 150 miles (241 km) is enough.

At 600 mph/1000 km (approximate, the same below), 400 mph/640 km, and 150 mph/240 km, we already have three potential answers.

This 1000km, not the other 1000km

Before continuing the topic of "not enough", it is necessary to clarify the "standard" issue. Because the "CLTC standard 1000km endurance" that domestic independent car companies have achieved, the 400 miles, 500 miles, and 600 miles that Musk and Lucid are competing with are not a different thing at all.

By 600 miles/966 kilometers, Musk clearly refers to 600 miles under U.S. EPA standards. The Model S has a maximum battery of 100 kWh to date, and its longest endurance version has an EPA range of 405 mph/652 km. The background board Lucid Air is equipped with a maximum of 118kWh battery pack, and the longest endurance version of the EPA has a range of 520 miles/837km, which is also the first model with an EPA life of more than 500 miles (which triggered this discussion).

Tesla's current limit, the maximum difference is 400 miles

As we all know, among the major endurance standards in the world's major markets, the US EPA is the most stringent one.

If you don't limit the endurance under EPA cycle conditions, as early as 2017, a Model S ran a single charge endurance of 1080km. And such an extreme attempt is successful, obviously can not be considered to really have a "1000km endurance" capability. The news event that we often hear about "so-and-so electric vehicle successfully drove xx km" is mostly a similar "deliberate" endurance.

Such extreme endurance attempts are often used by car companies for publicity purposes. Originally, this was beyond reproach, but it could not withstand the rumors of the carless common sense viewers. In 2020, Hyundai ran a single endurance of > 1000km with three Kona (domestically called Onsino EV), which seems to be insufficient, and take three to prove it.

In a test cycle with lower pressure than north American EPA in Europe's WLTP, the Kona EV's endurance performance is only about half of 1026km. In official information, Hyundai is also frank: the test was conducted in a simulated environment of heavy urban traffic. In this "1000km endurance", there is basically no high-energy high-speed driving, and it is likely that there are few brake actions that are not conducive to kinetic energy recovery.

Since the beginning of November last year, the energy consumption test of electric vehicles in China has officially switched from the previous working condition method of approximately NEDC cycle to the CLTC cycle standard. Before and after the switchover, it is obvious that the mileage number marked by domestic electric vehicles has increased out of thin air. For example, the Model 3 Performance has changed from the original 605km to 675km, while its cruising range in the EPA test is 507km.

The 1000km endurance under the domestic CLTC standard is not comparable to the "600 miles" (or 1000km) in Musk's mouth (in North America) and the EPA test standard. Tesla's longest endurance Model S on sale, the domestic label endurance temporarily follows the North American standard of 652km (405 miles), and when the CLTC test is completed, its CLTC endurance will be much higher than the number of "652km" (although the probability is not 1000km).

To be more durable is to be less anxious

Back to the question of how much is enough. According to the rough calculation of the approximate proportion of experience, Musk said that the "not worthy" is the EPA standard 600 miles, CLTC standard about 1200 ± km; and he believes that Tesla has met and exceeded the need for EPA standard 400 miles, if the endurance test according to the CLTC standard, will fall about 850 ± km (roughly calculated according to proportional experience, inaccurate).

The CLTC that has been achieved in China has a range of 1000km, which may indeed exceed the Tesla that currently has the longest battery life.

Musk's refusal to "thousand (gong) mile endurance" is full of reasons and old-fashioned, in addition to the inevitable problems caused by weight gain, it is more important that it is almost impossible to run such a long mileage on a single charge. Even if other endurance standards have "moisture", then EPA battery life can also explain the problem. Even if the EPA standard is not harsh enough, 400 miles and a 20% discount is about 500km, close to the daily limit of normal drivers (fatigue driving does not count).

But accounts don't always work that way.

The endurance of most fuel family cars is roughly in the range of 400-600km. If the electric vehicle actually has a range of 500-600km (which may require CLTC range of 700-800km), it has been achieved to keep pace with fuel vehicles. However, if the winter battery life is discounted, if it is still necessary to maintain the same level as the fuel vehicle, it is necessary to go further, perhaps reaching the CLTC standard of more than 800km.

Even if Tesla already has a dense and fast self-operated supercharging network, it does not dare to pat its chest at the moment to ensure that charging can be equivalent to refueling in terms of overall efficiency. This "overall" also needs to include the difference in the time between refueling and charging - gas stations may occasionally catch up with the queue, but the average refueling time is still much lower than the 30-40 minute charging time.

Home charging, slow charging, etc. can be used as a supplement, but at least for China, "one car and one pile" is still unrealistic in the near future. Then electric vehicles hope to become more mainstream, or rely on public fast charging facilities. Under such a premise, since the "overall efficiency" of charging is still not as good as (refueling), it is natural to make up for it with a longer single endurance.

From this point of view, at least at this stage, the single (actual) endurance required by electric vehicles is actually higher than that of fuel vehicles. The latter adds fuel every 400-600km, even if you count the occasional queue, the average time is difficult to exceed 10 minutes; the former charging even if it is not queued up to half an hour away, then the ideal single endurance needs to be significantly larger than the fuel vehicle, such as more than 600km (in order to be roughly equal in the whole).

CLTC standard 1000km, in a relatively bad reality, the actual endurance is likely to fall around 500km. If it is 1000km under the EPA standard, the above requirements are basically enough. So at least at this stage, the pursuit of 1000km endurance has practical significance: with a longer single endurance than a fuel vehicle, to make up for the disadvantages of energy replenishment facilities and energy efficiency. In this way, we will reduce the purchase threshold of electric vehicles, improve the experience of using electric vehicles, and attract more people to actively choose electric vehicles.

Of course, things are constantly evolving. If you look at the problem from the perspective of development, with the acceleration of charging rate, the increase in charging network density, and the increase in the proportion of charging parking spaces (including the popularity of public slow charging piles, which is very important), the pressure on the single endurance of electric vehicles will gradually decrease.

Talking about endurance away from infrastructure is all hooliganism

Peter Rawlinson, CTO of Lucid Motors, mentioned earlier, has a more extreme idea: a compact electric car of about $25,000 (probably the rumored Tesla Model 2 level), with only a 25kWh battery and an EPA life of 240km.

Because the battery is smaller and cheaper, such a compact electric vehicle is easy to afford, and the price can be equal to or even lower than that of the same level of fuel vehicles; because the battery is smaller, even the existing charging pile can be replenished in a short period of time (such as 10 minutes); although the single endurance is short, but with the density of charging facilities that increase with the popularity of electric vehicles, the convenience of daily use is easier to improve.

Peter Rawlinson's specific vision also includes some of the more stringent performance requirements that currently seem to be more stringent, but this does not prevent the idea from being discussed as a future option.

We know that driving for 4 consecutive hours requires a 20-minute break, which is based on human physiology. Combined with the needs of the human body to eat and drink Lhasa, for passenger car drivers, the rhythm of high-speed 2-hour ride rest for 10 minutes will not delay the trip more than the existing large battery electric vehicles. The 25kWh battery is combined with the existing 100kW charging pile, and it is not difficult to achieve 200km/10min (actual endurance) energy replenishment efficiency.

In fact, the pressure is shifted to the side of the charging network: such small battery electric vehicles require very dense fast charging facilities as support. This "very dense" means that the high-speed speed has at least one fast-charging station every 200 km; even, given the large increase in the number of electric vehicles envisaged, the density of fast-charging stations may be higher than the current density of gas stations. This is true at high speeds, especially in cities with fast and slow pile densities.

The idea of this idea is to "use a single endurance that is much lower than that of a fuel vehicle in exchange for at least not significantly higher than the cost of a fuel vehicle; and then use a charging facility density that is much higher than the density of gas stations to make such a short-endurance, low-cost electric vehicle still not inferior to the energy efficiency of existing electric vehicles." If you follow this line of thinking to the extreme, it will develop into what some people envision: all roads are paved with wireless charging, and family cars become "trolleybuses" without batteries.

On the one hand, this requires breaking through the dilemma of "chicken or egg first" and transforming into an infrastructure maniac who does not change his face; on the other hand, 25kWh achieves EPA endurance of 240km and peter Rawlinson calculates the low cost, which also needs more investment and time than the current technical conditions.

It is not that I agree with this idea of "as long as I am full of fast charging piles, I don't need batteries", but from this idea we can see again: the single endurance demand of electric vehicles is highly linked to the overall efficiency of the charging environment. This "overall efficiency" includes both fast charging networks and home charging penetration; both the density of charging facilities and the advancement of charging speed.

Under the overall efficiency, because in reality, there are charging barriers between brands, and the battery life requirements of different brands of electric vehicles are different. Tesla and Weilai are good examples, a charging network with the best comprehensive performance (density, speed, stability, etc.), a replacement power station with a rate reduction and dimensionality reduction, the former can rely on the 450km endurance of the standard version of the Model 3 to sell the blockbuster, the latter can still list the original 75kWh battery as standard.

For Tesla, with the best supercharging network support at present, 1000km or even longer endurance, it is really not worth putting high priority at all - not to mention that the 1000km they are talking about is EPA endurance. However, for those brands that are far less than the self-operated charging network, such as Lucid, the first to achieve EPA battery life of more than 500 miles, such as most of the domestic independent, joint venture, and new car brands, the battery life is still more and better at this stage.

The fact that others can does not mean that "I can too"; the future may be possible does not mean that "now can be".