Once, Gorky had a profound insight into the situation and society after the October Revolution, expressed strong indignation at evil in the name of "revolution", and had a persistent belief in the personality, dignity and freedom of thought of intellectuals; ten years later, he returned from overseas and plunged into the chorus of praise for Stalin's system. Soon after his return to China, he led the writing of "the shameful book in the history of Russian literature that praises slave labor for the first time in history" (Solzhenitsyn) – "The History of the Construction of Stalin's White Wave Canal".

Text/Golden Goose

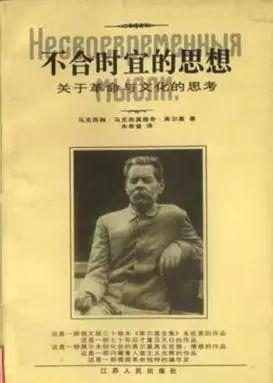

The Gorky anthology at hand, The Ill-timed Thoughts, puzzled me. From a historical point of view I have come to know something about the "difficult journey" of Gorky and his generation of Russian intellectuals, and before I read it I knew that in this book I would read of a "humanitarian Gorky", perhaps even a "liberal Gorky", who was different from the "petrel of the proletariat" before him and from the royal master of "socialist realism" that followed.

But when I actually started perusing the book, I was still confused. I marvel at the author's profound insight into the situation and society after the October Revolution, the strong indignation expressed in the name of "revolution", the understanding and persistence of the idea of democracy, the persistent belief in the personality, dignity and freedom of thought of intellectuals, the sharp comments on the dark side of the Russian people's national nature and its performance in the revolution, and the foresight in those unfortunate cases. Of course, his act of stepping up to the rescue of the politically displaced, regardless of his personal safety, during this period, was even more shocking to his solemn protest at the time when the Bolsheviks dispersed the Constituent Assembly that "the rifles dispelled the dreams for which the best Russian elements had struggled for nearly a hundred years."

It was precisely because he was so "out of place" that he finally had to embark on the road of wandering abroad. Up to this point, this Gorky is still something we can read, and this Gorky does not even contradict the "petrel of the proletariat"—because the "petrel" was also an "untimely" rebel in that era, and the "ill-timed ideas" of sympathizing with the weak, upholding justice, upholding humanity, protesting against the might, and so on can logically become the soul of the "petrel". After all, both the "petrel" and the "out of date" are playing the role of social critics or "dissidents", acting as a symbol of the hearts and minds of society, of human conscience and reason, and of the typical character of the so-called "intellectuals" of the Russian tradition.

Ten years later, however, he returned from overseas, plunged headlong into the chorus of praise for the Stalinist system, and behaved so "brilliantly" that he was no longer "opportune" in general, but slashing at the "untimely" instead of being a dissident in general; he was no longer a general dissident to a "dissident", and he was the first to shout bloodily at dissidents, suspected dissidents, and even those designated as dissidents so that other dissidents could climb up his corpse: " If the enemy does not surrender, he will perish! It was this Gorky who, soon after returning to China, led the writing of "the shameful book in the history of Russian literature that praises slave labor for the first time in history" (Solzhenitsyn) - "The History of the Construction of stalin's White Wave Canal", and the humanitarians of that year praised the labor reform project: "It is many times more difficult to process the raw materials of man than to process wood!" As for Gorky's performance in touting Stalin, it is not to be said that it is too meaty.

Of course, it has been explained that all this was imposed on Gorky. This explanation makes Gorky's later years almost like a prisoner, and even the cause of his death seems unclear: the authorities declared that the red literary hero seemed to have been assassinated by the "enemy of the people" during the Soviet purge. In the era of "thawing", some people invited the king into the urn and put the charge of the assassin on the head of the Stalin authorities.

If so, Gorky does not seem to be "difficult to read", but serious historians seem to support this argument very little, just as they do not support stalin's tyranny because he was a secret agent of the Tsar.

So we have to admit, at least until there is no new evidence, that Gorky did undergo an inexplicable transformation.

Consistent idealist?

As mentioned earlier, Gorky's journey from "Petrel" to "The Untimely" is not difficult to explain, because the two can be strung together in a humanitarian spirit. If Gorky had not been an "out-of-date" (as we had before the reforms), his journey from the "proletarian petrel" to the "red literary magnate" is not difficult to explain, for the two can be strung together with the beliefs of "socialism". In the former case, Gorky's image is like that of The Noble Revolutionary Guo Wen, described in Hugo's "Ninety-Three Years", who let go of the nobility out of a more noble humane spirit than the revolution. In the latter case, his image is like that of the Q-style "revolutionary" who firmly believes in "the poor and lower-middle peasants fight in the country and sit in the country".

However, the transformation from "untimely" to "red literary hero" is really puzzling, because it is like Guo Wen becoming Ah Q, and its incredible degree is far better than the Transformation of Marquis Landenac into Guo Wen, and also far better than Ah Q becoming Zhao Taiye. The point is that, according to people's usual opinions, a change in beliefs and even a change in "class position" is easier to explain than a change in personality. It would not be surprising if one believed in liberalism before one converted to socialism after much deliberation, or vice versa; one believes in socialism and then in liberalism. It is not surprising if one is originally loyal to the "feudal dynasty", re-takes sides in the face of social changes and instead serves the "bourgeois republic". But if Guo Wen becomes A Q, it is as unacceptable as Prometheus becoming a city thief – although from the perspective of "ism", perhaps Prometheus's "stealing" fire and thieves stealing money can be interpreted as some kind of "ism" that flouts property rights.

In order to avoid confusion about this interpretation, many people try to find "the consistency behind the two extremes of Gorky" (press: "inappropriate" and the royal master) from the "isms", trying to prove that "it was the factors that prompted him to oppose the October Revolution that led him to embrace the Stalinist system". (Reading, No. 11, 1997, pp. 70-71, Cheng Yinghongwen.) These commentators also argue that "this twist and turn of Gorky is to some extent quite representative of the intellectual friends or fellow travelers of the radical revolution, those who coincide with the revolutionary time and time, although they have a disagreement, but still agree with it in the end, but not as dramatically as Gorky." ”

I can't agree with that. The problem is precisely that those people are "not as dramatic as Gorky". I am afraid that this difference cannot be easily "stopped". Indeed, there were many intellectuals who sympathized with the revolution but found it "excessive", who agreed with change but feared that its "cost" was too high, who agreed with its aims but disliked its bloody methods. It is true that they are "in tune with the times" of the revolution, but as long as their personalities are not distorted, they will not be "in harmony" so "dramatic". It is conceivable that they will tolerate the blood in front of them for the rainbow of the future, but they may not be able to exalt blood. And in the process that follows, they often find it difficult to escape the choice between the two: either they are "divided" because they refuse to praise blood or even because the praise is not high, or they sacrifice their personality against their hearts—and in the latter case it can no longer be said that it is "the noble human spirit that "leads" to this praise.

Moreover, judging from Gorky's "untimely thinking", his attack on the October Change has become more than just criticizing its means and agreeing with its direction, sympathizing with its purpose and worrying about its "excesses". He accused the Bolsheviks of firing rifles for dispelling the dream that Russia's best had fought for for nearly a hundred years, rather than accusing it of paying too much of the price it paid to realize it. Under the title "January 9 and January 5", he equates the 1918 crackdown on demonstrators who supported the Constitution with the Tsar's suppression of petition workers in 1905, apparently not to think that the revenge for the 1905 massacre was too intense.

Indeed, if it is true that the idealistic identity caused Gorky to abandon the opposition position regardless of the differences of means, then it is only logical that this should have happened in lenin's time. Indeed, even those who oppose the October Revolution tend not to deny that there is a certain degree of idealistic passion in the revolution, and from Lenin to Stalin there is an undeniable tendency for this passion to fade and to give way more and more to the pragmatism of vested interests. It was on the basis of this "fellow traveller's ideal" that menshevik scholars such as the Menshevik scholar П.П. Maslov, the bender chieftain Д.И. Zaslavsky, and a large number of "fellow travelers" such as B.B Ivanov, П.А. Piliniac, А.Н. Tolstoy, etc. completed the transition from "dissent" to "identity" in lenin's time. By the 1930s, such a turning point was hard to come by. The tide of intellectual "repentance" that occurred at this time was the same as the "submissive" trend of the opposition within the Party, and if it were not forced to survive under pressure, selling arguments, or being insensitive and accompanying the market, I am afraid that there would be a more metaphysical component. Of course, it cannot be said that the society of this era is not idealistic at all, but if this residual "idealism" can inspire Gorky and make him turn, how could he have insisted on not getting along with Lenin in the first place?

Gorky and Stalin.

Infected by Soviet achievements?

Or, in other words, what "inspired" Gorky was not the idealistic passion, but the achievements of Soviet construction. "Seeing That Russia become a large factory in an orderly manner," Gorky fulfilled his "dream of a great power," and he was convinced to abandon the values for which "the best russian elements have struggled for the past hundred years." But if Gorky was such a "power-maker", he should have been loyal to the Tsar in the time of Stolypin, because Russia, which had suppressed the petitioners of "January 5", also had unprecedented economic prosperity that year.

I therefore believe that it was by no means the "factors that prompted him to oppose the October Revolution" that led Gorky to "embrace the Stalinist system", or even the factors that made him the "petrel of the proletariat". (Chinese translation of "Untimely Thoughts" by Jiangsu People's Publishing House, 1998 edition.) The back cover contains the editor's words: "Gorky is a forest with trees, shrubs, flowers, and wild beasts, and now all we know about Gorky is that we have found mushrooms in this forest." ”

The question is where did this "mushroom" grow? Is it on a robust "tree", or in a decaying wood?

Among those who have changed from "discord" to "identity", there are various types of people who originally sympathized with the revolution and then forgave the bloodiness of the revolution because of the "ideals of fellow travelers". For example, some people, from the standpoint of nationalism and patriotism, believe that no matter what "ism" and what means are used, it is good to make Russia strong and defeat the enemy. Many of the Belarusian diaspora during World War II included many such people, and even the former commander of the White Army, Denikin, paid tribute to Stalin and asked him to resist Germany.

Others are motivated by a kind of "peaceful evolution" and "curve transformation", which is typical of the "signpost shifters" represented by the former Cadet H.B Ustrialov. Just as the Stolypin reforms of that year made many opponents of the Tsarist authorities think that external resistance was not as good as internal advancement, and thus published a collection of "Road Signs" announcing a change of course and reconciliation with the authorities, in 1921 the Soviet government abandoned "wartime communism" and switched to a new economic policy, and a certain degree of economic liberalization occurred, which also gave some opponents of the regime the idea of changing external resistance to internal advancement, so the "Road Signs Conversion" collection and the magazine of the same name appeared among the Belarusian diaspora. Among them, Ustrialov and others returned to China in 1935 to serve Stalin, completing another process of "discord to identity".

Gorky's journey is clearly different from all of these people. His "transformation" is neither out of "fellow traveler ideals" nor nationalist or "signpost shifting" consciousness, so what is the reason? Researchers accustomed to looking for "motives" from metaphysical perspectives have so far failed to provide a credible explanation.

Not complicated by the truth

Why, however, do we have to drill the tip of the bull's horn on a metaphysical level? Until there is no new evidence to support these metaphysical "motivational theories," we might as well imagine: Maybe things aren't that complicated in the first place? Maybe the way of thinking of ordinary people understands all this better than the way of thinking of scholars? Maybe our great writer doesn't live in the metaphysical world all day, and he will also have metaphysical considerations? Maybe the transition from Guo Wen to Ah Q is not so incredible, but maybe it is not as "intellectual history" or more "academic" as "from Langdenak to Guo Wen" or "from Ah Q to Zhao Taiye"? Maybe Gorky's mechanism of transformation is not a question of thought, but more of a question of personality?

It wasn't "maybe", as early as when Gorky was still an "outdated man", he had already revealed his bitterness in a letter to his ex-wife: he was "tired of text protests that had no practical effect". Gorky is not Lu Xun, and he will not indulge in the "desperate war of resistance"; if he knows it, why should he do it; tragedy is difficult to perform, how can comedy be? Given the "practical effect", Gorky had to be "in time". Of course, maybe he didn't want to be "fit" to that extent later, but that's up to him! In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stalin had already tried his way against "fellow travelers" before he went on a killing spree against the opposition (or "opposition suspects") within the Party. From the Shacht case to the "underground party" prisons such as the "Industrial Party," the "Toil peasant party," and the "Menshevik League Bureau," the "fellow travelers" have long since changed their minds, let alone "out of date." Gorky's return at this time may not be purely for "reasons in the history of ideas", but since he returned, with his identity and performance in that year, can he not "fit the time" and "fit" to the maximum?

Of course, one of the criticisms that such an explanation is likely to provoke is: Would the great writers be so subservient to power? Look at how righteous and awe-inspiring he was in the face of tsarist despotism! But on this point, Solzhenitsyn has already made a convincing explanation in his writings: that kind of despotism is too pediatric than the "gulag"! It is not surprising that the personality that has been tested in pediatrics is now distorted.

As a result, the book "Untimely Thoughts" gives people too much emotion. This book undoubtedly enriches Gorky's image as a profound thinker, but it also gives us a glimpse of a caricature of personality. Without these ideas, Gorky, from "Haiyan" to "Red Literary Hero", gives the impression of a simple leftist writer, like an "old poor peasant with a bitter vendetta", although it is not profound, it is a little cute and naïve. After knowing these thoughts, it is inevitable that people will take a breath of cool air while being amazed: Do we still need to be careful to oppose the "Left"? These people originally understood everything, but we fooled people seemed too stupid and too stupid!