Text/James Morris

The marketing of hydrogen fuel is heating up, though not as effective as the Hindenburg of 1937. (The Hindenburg airship was a large German passenger-carrying airship fueled by hydrogen that burned on May 6, 1937, while attempting to land over lake-Navy Terminal in Manchester, New Jersey.) In britain, there are even ads for this fuel on the London Underground, and their posters, posted next to the latest iPhones and vitamin supplements, look rather strange. After all, the average company employee doesn't rush out to buy some hydrogen fuel on the way to work or before they get to the office. No, it's more of a signal that there's a PR campaign that's embedding hydrogen fuel into the public imagination as a savior for all of our lifestyles in the face of climate change.

For consumers who like to read tabloids, this is already in effect: there are already many who claim that they will not buy pure electric vehicles because they are "waiting for hydrogen fuel cars". But a bigger problem is that governments are also listening to these opinions, and that is not necessarily a good thing. Recently, the EU pledged to use 2.6 percent renewable fuels, such as green hydrogen (produced from renewable sources such as wind and solar), and replace 50 percent grey hydrogen (produced from methane) with green hydrogen. It would be nice if we had enough renewable energy to use, but we didn't. Transport & Environment, a research institute, has found that doing so would put undue pressure on the wind and solar energy we own, which are urgently needed and urgently needed for other applications.

The UK government also places a lot of emphasis on hydrogen energy, even giving some staggering figures about how many jobs the industry will create by 2050 and how much the sector is worth (specifically, 100,000 jobs and £13 billion/$17 billion). The UK has shifted many of its power generation networks to renewable sources, especially wind, and now more than half of the country's electricity comes from wind. But that doesn't mean there will be a lot of surplus electricity for hydrogen energy production. Optimistic job opportunity and market value forecasts seem to hide some of the main obstacles.

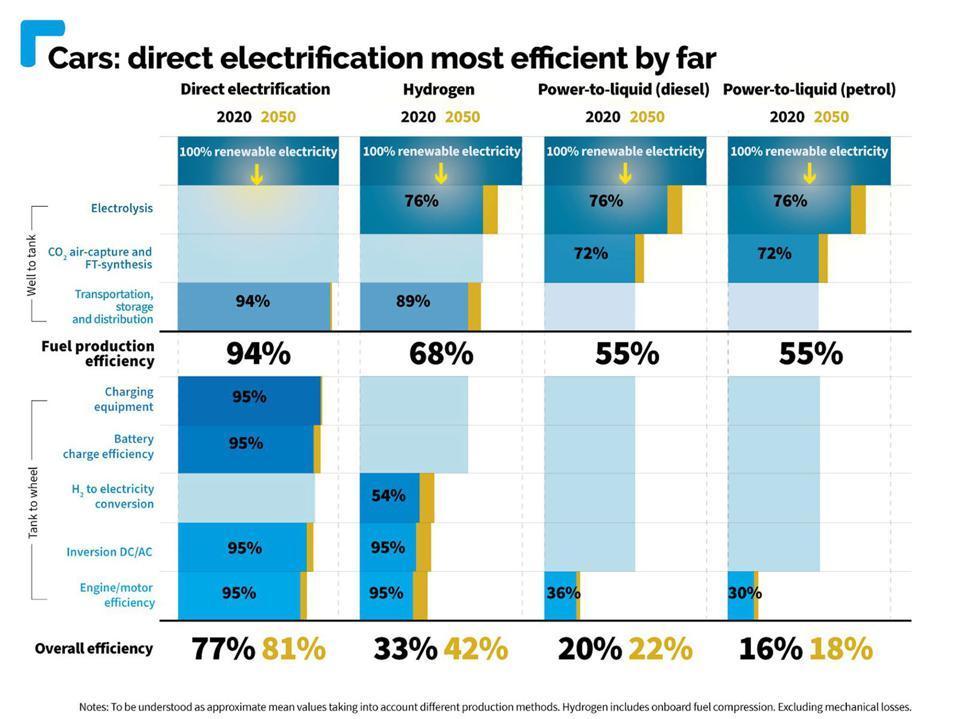

The laws of physics don't support hydrogen energy very much, because the energy efficiency of hydrogen fuels is really low compared to batteries. Image credit: Transport & Environment

This could undermine our path to decarbonization rather than make it easier. Arguments against hydrogen fuel as our savior are becoming increasingly well known, and mostly revolve around the laws of physics. There may be a lot of hydrogen in the universe, but it's not easy to harness it. While there are ways to obtain hydrogen as a by-product of other processes, it usually has to be extracted from fossil fuels or electrolyzed water. The latter is a truly eco-friendly option, but requires a lot of energy and loses about a third of the power input compared to sending it through the grid. The losses are greater if fuel cells are used to convert hydrogen into electricity, and even worse if hydrogen-derived synthetic fuels are used. Efficiency is expected to improve only slightly over the next few decades.

The main advantage of hydrogen fuel is convenience, which seems to be the core reason to trumpet it. Hydrogen fuel fans are concerned that hydrogen fuel cars, like fuel cars, only take 5 minutes to fill up energy. Even more enticing, hydrogen messengers are being fed a story that they will soon be able to use hydrogen-based synthetic fuels in the cars they now drive without having to make any changes.

The spread of these ideas seems to be aimed at delaying the spread of pure electric vehicles. Still, at least in Europe, it doesn't seem to be working yet, as EV sales here are rising every month. In the UK, pure electric vehicle sales in November this year were doubled from November 2020, while pure electric vehicle sales in November 2020 were doubled in November 2019. By comparison, there are only a few hundred hydrogen-fueled cars in the UK. Of course, at least in the automotive industry, if hydrogen fuel can save us, it's better to hurry up, so as not to be too late.

Hydrogen applications will be essential in some areas, and the focus should be on those areas – not on transport. Image credit: LIEBREICH ASSOCIATES

The problem with all the unrealistic positive rhetoric about the use of hydrogen fuel in cars is that this fuel type does have a place in a decarbonized energy economy, but its inefficiency must be balanced with its convenience, as well as focusing on where direct electrification can't be achieved. Michael Liebreich of the Bloomberg New Energy Foundation (BloombergNEF) has created a pyramid of relative value for convenient different hydrogen use scenarios, where scenarios like fertilizers are essential for the use of hydrogen energy, but any form of transportation, from trucks and coaches to short-haul aviation, is best served by batteries or other forms of electrification. German think tank Agora Energiewende coined a term to refer to the basic application of hydrogen fuel as a "no regrets" scheme because the demand for hydrogen fuel is uncontroversial, and batteries have been shown to serve transportation more efficiently.

The frenzy about the future of hydrogen fuels has only provoked a huge negative reaction from those who are already driving pure electric vehicles, because they realize that pure electric vehicles are not just the future, but the here and now. This reduces the use of hydrogen energy, for example as a portable energy source in areas where there is no grid. The "Extreme E" racing series uses a hydrogen generator as a clean way to generate electricity, charging its battery-powered SUV racing cars.

The problem is that the fundamental struggle is between two types of energy suppliers – grid providers and oil and gas companies. The latter generally leans toward hydrogen fuels, as most hydrogen fuels are currently made from methane or coal. They also want to maintain their own financial model, forcing consumers and industrial customers to source fuel elsewhere, rather than supplying it to their homes and businesses. Electricity providers, by contrast, want to sell more electricity wherever they can supply it.

Sales of fuel cell vehicles currently lag behind pure electric vehicles. Image credit: LIEBREICH ASSOCIATES

The real question should be: "Which energy source is the greenest?" The answer to this question lies primarily in the need for governments to recognize which are the best use scenarios for hydrogen energy and invest accordingly. The European Union, for example, is re-shifting the focus of hydrogen fuel applications away from personal mobility, but not entirely away from transportation. There are some possible effective use cases, but except for some very special cases, in all cases, there is little reason to use hydrogen fuel in the transportation sector. Cars are largely not one of these possible effective use cases, which is why the words that are still preaching hydrogen-fueled vehicles today sound like cults. As Agora Energiewende's report concludes: "Just a decade ago, fuel cell electric vehicles seemed like the future of the automotive industry. Today, this dream is over."

Translated by Vivian School Li Yongqiang

The author of this article is a Forbes contributor and the content of this article represents the views of the author only.