Text/Sophia Goodfriend; trans/ Gong Siliang

Editor's note: In July, several news outlets uncovered how the Pegasus software service of an Israeli company, NSO, was used by different people or organizations to spy on opposition and dissidents, journalists, and ordinary people in many countries. However, after interviewing a number of employees of Israeli cyber espionage companies, the author found that the criticism from the international community did not attract the attention of Israel's high-tech community. For veterans working in Tel Aviv's high-tech community, they have become accustomed to ignoring the moral consequences of their work and enjoying the rewards of their work. Veterans have shifted "surveillance skills in the name of national security" through the "fast track" established by the Israeli government in the military and high-tech sectors to the largely unregulated private sector, which has also been conducting surveillance without the consent of the masses. Journalists, civil society organizations and politicians are now working together to demand that the private surveillance industry comply with international human rights standards, which could bring about change. But more importantly, employees and the public need to be aware of the significant dangers behind Israel's private surveillance industry and stop seeing these jobs as "harmless" high-paying occupations. Originally published in the Boston Review of Books, this article is written by Sophia Goodfriend, a ph.D. student in cultural anthropology at Duke University. Her PhD research is at the intersection of scientific and technological research, surveillance research, and digital rights.

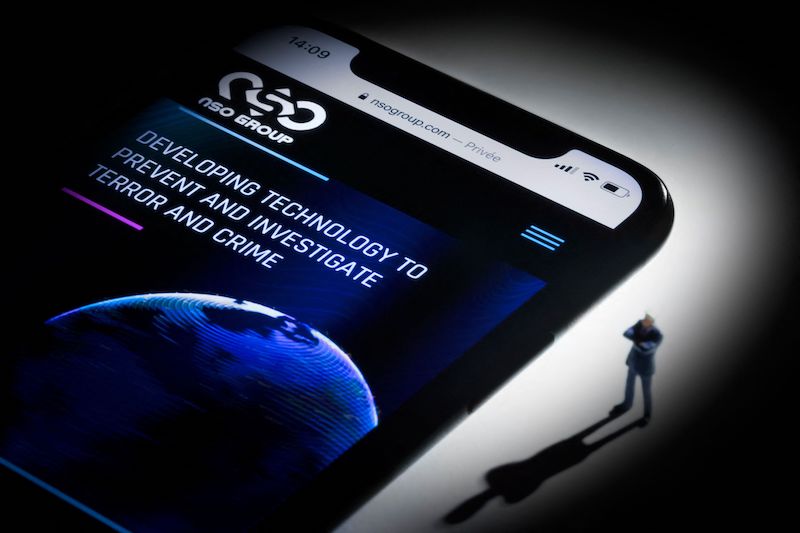

Pegasus

This summer, a coalition of 17 media organizations published a series of articles accusing Israeli cyberespionage firm NSO Group. The coalition of journalists, in partnership with civil society groups, claims that thousands of dissidents, human rights workers and opposition politicians around the world have been targeted by the NSO's Pegasus spyware. A U.S. White House spokesman denounced the act as "extrajudicial surveillance," which sparked outrage around the world. However, almost no one in Israel's isolated high-tech community was shocked by the news.

Last month, J, who worked for a spyware company in Tel Aviv, told me over coffee in downtown Tel Aviv: "Here, the whole ethical issue is downplayed. "I asked J why, in Israel's high-tech ecosystem, so few people seem to care about a new round of criticism of the NSO Group. J, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said it was a cultural issue: Most employees at private monitoring companies "get attracted to a variety of conditions: salaries, holidays, cool work atmospheres and offices." "It's not uncommon in Tel Aviv," he says, "you may be selling software to a company that doesn't respect human rights, but people don't think deeply about it because they make a lot of money and spend all day working in nice offices." ”

NSO Group is one of the "few small spy software companies" that has entered Israel's high-tech space over the past 10 years, selling espionage features that were once the preserve of military superpowers. Most of these companies have offices around the world, such as the National Security Agency or the Israel Defense Forces' Unit 8200, and include developers and analysts poached from the world's top intelligence agencies. These companies sell their ability to invade the privacy of anyone, anywhere in the world, to the highest bidders: whether it's a dictatorship like Saudi Arabia or a private criminal like Harvey Weinstein, and they make millions of dollars. Revelations this summer revealed his crimes: An investigation report found NSO's Pegasus software on the phones of some 50,000 unsuspecting civilians, including journalists and their teenage children, prominent politicians such as Emmanuel Macron, and political dissidents in Bahrain.

Despite international media and regulatory bodies such as the United Nations condemning human rights abuses by the NSO, no one in Israel's high-tech ecosystem seems to be concerned about these disclosures. To many in Israel's tech community, NSO is just another high-tech company that "performs military-grade espionage" in an industry known for its military espionage skills. In Tel Aviv, the capabilities of IT specialists with military training backgrounds are sought after by global tech giants, emerging startups and small cyber espionage companies. The work they do, including professional data analytics, cybersecurity, digital espionage, is more or less the same, except that it has shifted from the military to the civilian field. The difference is in the impact of the work: Critics accuse the cyberespionage industry of fueling massive human rights abuses around the world by silenceing journalists and suppressing political dissent.

NSUI activists holding placards and chanting slogans protesting the Modi government's use of pegasus, the military-grade spyware of Israel's NSO group, Pegasus, to spy on political opponents, journalists and activists, on Aug. 2, 2021.

Like many Israeli cybersecurity companies, NSO Group was founded by alumni of the 8200 Cyber Force. The force is the elite intelligence unit responsible for monitoring Israel and the Palestinian territories. The operations of Unit 8200 remained secretive for decades until 2000 and mid-2010, when Israel's private high-tech sector made its way to the global market. It was the dawn of the post-9/11 surveillance nation, and Israel's military establishment was updating its often-lauded espionage capabilities to meet the demands of the digital age. The Israeli military has invested millions of dollars in cybersecurity, and its surveillance of Palestinian territories has facilitated experiments with new forms of cyber espionage. In response, Israel has trained a cadre of IT experts who can translate their military experience into the emerging digital economy.

At the time, to borrow words from Dan Senor, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and Saul Singer, editor of the Jerusalem Post, Israel was reinventing itself as an innovative "startup nation." Startups responsible for cybersecurity proliferated, and lucky startups were soon acquired for millions of dollars by one of the global tech groups that opened branches in Israel. Skyscrapers rise to the ground in downtown Tel Aviv, and their open-plan floor design mimics the image of Silicon Valley: offices are filled with bean bag chairs, cask beer and mini oat bars. Like the Bay Area, Tel Aviv attracts young, highly educated, high-tech employees, mostly men. But unlike in the Bay Area, most of the high-tech workforce comes directly from the Israel Defense Forces. Few people can turn down the opportunity to apply espionage techniques learned in the military to the booming private sector and make millions of dollars.

Shoshana Zuboff describes this era as the dawn of "surveillance capitalism." This is an era when global tech giants gain economic and social power by expropriating users' data for advertising and their own analysis and programming. Sometimes, tech companies share that data with the government, which outsources some of the state's surveillance to companies like Google. Over the past few decades, the lines between corporate and state surveillance have become almost indistinguishable: tech platforms have produced unregulated databases of user behavior that governments often mine for national security purposes. In this way, some programmers at Google are doing the same job as programmers at cyberspionage companies: tracking users and sharing their data with the highest bidder.

The overlap between state surveillance and the digital economy explains why many countries have set up a "fast revolving door" between the military and high-tech sectors to switch industries. In countries like the United States, internal dissent over such collusion is growing, at least nominally. In Israel, however, veterans of the IDF's combat or technical forces make up 60 per cent of the high-tech workforce. These forces offer a unique culture that permeates Israel's high-tech sector: a common set of values, references and standards of practice that are intertwined in a given environment. To borrow the words of Israeli politicians and military generals who now sit on the boards of lucrative tech companies, the culture is "risk-taking" and at the same time "positive, some would say it's a blind belief that things will all be okay." As Inbal Arieli, head of business and Unit 8200 alumnus, put it in her book Cheeky: Why Israel is a Hub for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2019). This culture fosters highly skilled, motivated engineers and developers who can devote themselves to long hours of work, efficiently solve complex problems, and lead large teams to perform sensitive tasks.

Today, this culture also discourages many people from exploring the moral implications of their work. Intelligence veterans are eager for a six-figure starting salary to apply the offensive cybersecurity skills they learned in the military to the private sector. They are less willing to question the moral consequences of outsourcing military intelligence capabilities to the highest bidder. In an interview in Tel Aviv in early September, G, a veteran of Unit 8200 and CEO of Cybersecurity, confessed to me: "We really don't need to think about the ethics of this work, and we certainly don't get used to it." "Many veterans are well educated and can even oppose the occupation, but still sell their skills to authoritarian regimes operating in Congo or elsewhere," people continue to work for companies like NSO, G said, because "they earn huge salaries at the age of 22." ”

Intelligence veterans aren't used to parsing the chaotic ethics of cyber espionage either. The services of the intelligence services are largely seen as free from the moral dilemma of combat; technical skills are considered more politically neutral than military conduct. In fact, many of the intelligence officers come from the wealthy and liberal strata of Israeli society and work hard to work in the intelligence services to avoid carrying out tasks such as raids on Palestinian homes in the West Bank. According to Unit 8200 veteran M, whom I spoke to over coffee in Jerusalem, the intelligence agency "is more like a professional organization and more like a startup than the military." Soldiers enjoy a clean, well-equipped, well-perked base: weekly game of Thrones screenings, private lessons with for-profit industry leaders, and regular socializing in Tel Aviv's skyscrapers. As M puts it, all of these perks "make it easier for people to feel like , 'I'm not serving the profession, I'm just writing code for people who serve that profession'".

Hiring a network also leads young veterans to think that working as cyberespionage is no different than working in other high-tech industries. For example, those who served in Unit 8200 made connections through the "Alumni" page on Facebook. One of my interviewees allowed me to browse the site. Join the Boutique Monitoring Company's ads sandwiched in the recruitment of startups that develop dating apps and financial management. Both types of ads are often accompanied by images of young people in their 20s wearing matching company shirts, smiling, and rooms piled high with modular furniture. A "digital identity solutions organization" needs a research analyst who is "proficient in English/Arabic" and "has a deep understanding of radical Islam." Look further down, a spyware company investigated for human rights abuses is beckoning to graduates who crave "exoticism" and whose salaries will surprise you ("rub your eyes"). Below that, a mobile gaming app calls on "creative coders" to join a company with "great culture and incredible benefits."

A woman in Nicosia, Cyprus, on July 21, 2021, is viewing a website where Israel makes Pegasus spyware.

Lists of cyberespionage jobs are regularly posted to the point that they look mediocre, advertising a trendy, high-tech model of affluence that is desirable but not out of line. In fact, cyber espionage companies are no different from the lifestyles offered by the less evil high-tech sector. In Tel Aviv, privatized surveillance companies are located in office buildings carrying dating apps, gaming platforms and biomedical imaging equipment. Developers from Microsoft or WAZE go out drinking with developers from Black Cube or NSO. Together, they discuss career stress, dramatic events in the workplace, and strategic career development. Every day, they collect data from individual users or find out what's missing in their operating system to produce better products for their customers. Of course, the difference is in the product.

When cyber espionage is normalized like any other high-tech service, even those who want to stay away from the industry will find themselves caught up in private surveillance. In late September, when I was drinking at a roadside bar in Jerusalem, former intelligence analyst S told me how she joined a fintech startup directly from the military. It was late 2019, and at a time when news of regimes like Saudi Arabia using Israeli spyware was revealed, she was excited to work in a less shady high-tech industry. When joining the company, S hopes to spend his time researching global financial markets. Instead, she found herself conducting research for the Israeli arms group and editing files of supporting BDS activists. "Surveillance is inevitable, but it's all caught between normal research on global investment trends," she stressed. If you want, it's easy to overlook how different one task is from another. ”

Most of the intelligence personnel I spoke to familiar with Israel's cyber espionage industry agreed that Israel's closed culture of high-tech is unlikely to change anytime soon, especially as international anger at the NSO group fades in the media. "Bad companies aren't going to stop recruiting Israeli talent," former developer J assured me, "and most people I know will continue to be drawn to the job because the pay and benefits offered by the job are getting better and better." From this point of view, criticism is a bit like background noise. ”

So rather than pointing out the ethical issues of a company, the NSO Group scandal illustrates the decay of digital economy culture, which is a problem for Israel and the world. In this case, in a sense, such a scandal is inevitable. Those who equip and manage Israeli high-tech companies come from military intelligence; veterans effortlessly transfer surveillance skills in the name of national security to the largely unregulated private sector, which has also been conducting surveillance without the consent of the masses. Journalists, civil society organizations and politicians have banded together to demand that the private surveillance industry comply with international human rights standards, which could bring about change. But to really rein in the industry, we need to make sure cyber espionage is no longer seen as just "another kind of office work."

Editor-in-Charge: Han Shaohua

Proofreader: Liu Wei