The 1830s and 1860s were the "golden age" in the history of Russian literature, during which a large number of influential writers and intellectuals stood out. In 1825, with the failure of the aristocratic revolution represented by the "Decembrist Uprising", the harsh era of the reactionary rule of Tsar Nicholas I became a new reality. Pushkin, now known as the "founder of modern Russian literature," took the lead in the stage of the times, and his work was a mirror of Russian society at that time, but it also became the object of close scrutiny by the Tsarist government. As the thinker Herzen said: "Only pushkin's loud and vast song resounds in the valley of slavery and misery, a song that inherits the times of the past, enriches the present day with a brave voice, and sends its voice to that distant future." ”

For a new generation of literary youth, Pushkin was their common guide. The poet Lermontov was deeply influenced by it, and his early works drew on Pushkin's style and often portrayed in his poems a Byronian hero—appearing as a banished and avenger, determined and indifferent against the world. In 1837, Pushkin was wounded and died in a duel with Dantes, an officer of the Tsar's Janissaries. At that time, Lermontov had not yet entered the circle of closest relations with Pushkin, and the two did not know each other. However, the Death of the Poet, which he wrote immediately after learning of Pushkin's death, caused a sensation. In the poem, Lermontov bluntly stated that the nobility was the real culprit in Pushkin's death, portraying high society as a group of selfish villains who were "executioners who killed freedom, genius, and glory." Afterwards, Lermontov was arrested and exiled to the Caucasus. But at the same time, he also rose to fame as "Pushkin's heir."

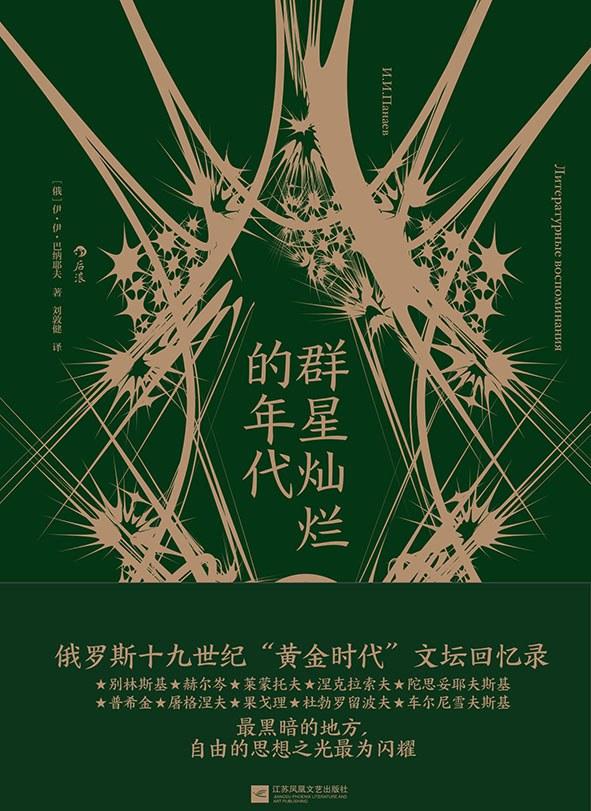

In a way, Lermontov and Pushkin had similar life experiences. They were both from aristocratic backgrounds and well-educated, but dissatisfied with the drunken and death-dreaming life of the aristocratic class and the blind obedience to the tsarist autocracy; they both explored the direction of society through poetry, but they were exiled, and their works were difficult to publish; more coincidentally, both died in duels with others. The Russian writer I.I. Banayev, in his literary memoir The Age of the Stars, pointed out that although Lermontov realized that Pushkin's death stemmed from his high-society habits, the former could not escape the attraction of high society, "he is exactly the same as Pushkin, and if anyone regards him as a literary man, he feels insulted." ”

This high-society habit was widespread in literary circles in the 1830s, and Banayev, then a rising literary talent, began to realize the enormous harm it did to writers and their works. His literary friend Belinsky also noticed that there was a "pitiful, naïve reverence for authority" in the literary world, and that people did not dare to publicly criticize the nobility. Banayev was also born into an aristocratic family, but from a young age he was fascinated by literature and had no interest in official promotion. In 1834, through his published works, he came into contact with the literary circle with Pushkin as the core, witnessing the legendary past of the literary masters of this period such as Lermontov, Gogol, Herzen, Turgenev, Dostoevsky, etc., and also saw their unknown character qualities and daily life.

<h3>

The Age of the Stars (excerpt</h3>).

Text | I. I. Banayev translated | Liu Dunjian

Some literary activists of the twenties, thirties and forties were susceptible to the so-called habits of high society, a tendency that was very unfavorable to themselves and to their work. Even such influential geniuses as Pushkin and Lermontov often fell into this tendency.

At all costs, Lermontov's first gain was his reputation as a high-society figure. He was exactly like Pushkin, and if anyone saw him as a writer, he felt insulted. By the way, although he realized that Pushkin's death was due to his high-society habits, and although Lermontov sometimes wanted to throw iron verses at the people of high society, he could not get rid of the prejudices of high society, which was still very attractive to him.

Lermontov was famous for his poem "The Death of the Poet", but before that, when he was still a student at the Non-Commissioned Officer's School, his outstanding poetic talent was rumored to be circulated in the form of a manuscript. It was only after his story about the merchant Karashnikov was published in the Literary Supplement of the Russian Newspaper Leon Jung, edited by Mr. Krajevsky, that literary critics began to pay attention to him.

<h3>01 A naughty boy who always takes others as victims</h3>

I first met Lermontov at a gala at the house of Duke Ordoevsky.

Lermontov's appearance is outstanding.

He was not tall, of muscular body, with a large head and face, a broad forehead, and deep, intelligent, and sharp black eyes. When he stares at others for a long time, it will make people feel embarrassed. Lermontov understood the power of his eyes and liked to use his persistent and sharp gaze to embarrass those who were timid and nervous. Once he met my friend Miya Yazekov at Mr. Krajevsky, and Yazekov was sitting opposite Lermontov, and they did not know each other at the time, and Lermontov stared at him intently for a few minutes, and Yazekov felt for a moment that his nerves were strongly stimulated, and he could not bear the look in his eyes, so he got up and went to another room. He still hasn't forgotten it.

I have heard Lermontov's classmates and teammates talk about him many times. According to them, there were not many people who liked him, except those who were close to him, and he rarely talked to them. He liked to look for something ridiculous in each of his acquaintances, for some kind of weakness, and once he found it, he repeatedly pestered that person, often making fun of him until others couldn't stand it. When others finally started the fire, he felt very comfortable.

"Strange to say," one of his companions once said to me, "he is not a bad man: drinking and having fun," he did not fall behind everyone in any way, but he was not at all gentle with people, and he always took others as victims, otherwise he would not be at peace; whoever was chosen to be a victim, he would cling to them. He inevitably suffered this tragic end: even if Martinov did not kill him, he would be killed by others. ”

In terms of the scope of acquaintance and communion, Lermontov belonged to high society, and he met only literary figures belonging to this class, only literary authorities and well-known figures. I first met him at Odoevsky's house, and later I often saw him at Mr. Krayevsky. I do not know where and how he befriended Mr. Krayevsky, but he was quite close to him, even commensurate with you.

Lermontov usually came to Mr. Krajvsky in the morning (in the early days of the Chronicle of the Fatherland, in 1840 and 1841) and brought him his new poems. Krajski's studio was lined with oddly styled tables and shelves of books and newspapers, neatly arranged with books and newspapers, while the editor-in-chief sat at a desk and looked down at the proofs, looking solemn and dressed in an alchemist's costume. Lermontov always went into his studio with loud noise, came to his desk, scattered his proofs and manuscripts all over the floor, and made a mess on the table and in the room. On one occasion he even knocked the learned editor-in-chief out of his chair to the floor, causing him to scramble through a pile of proofs. Mr. Kraevsky, who has always behaved in a steady manner, is accustomed to an orderly, careful and meticulous style, and should not like such jokes and naughty moves, but he has to endure the actions of this great genius whom he is worthy of you, and always says with a half frown and a half smile:

"Alas, enough, enough... Don't make a fuss, dude, don't make a fuss. Look at you naughty boy..."

In such moments, Mr. Krayevsky is very much like Goethe's Wagner (note: the doctor in the poetry "Faust"), and Lermontov is like a little ghost that Mephistopheles (note: the demon in the poetry "Faust") secretly sent to Wagner's side and deliberately disturbs his deep thoughts.

When the scholar cut his hair, patted his clothes, and returned to normal, the poet began to tell interesting stories about himself in high society, read his new poems, and then got up and left. His visits were always very short.

<h3>02 Lermontov as an ordinary man and Lermontov as a writer</h3>

On the day of Lermontov's duel with the son of the French Minister in Petersburg, Mr. Barante, I also met Lermontov with Monsieur Krajev... Lermontov drove straight to Mr. Krayevsky after the duel and showed us a wound on his arm. They fought with long swords. That morning Lermontov was unusually cheerful and spoke incessantly. If I remember correctly, Belinsky was also present.

Belinsky frequently met Mr. Krajevsky at mr. Lermontov. On more than one occasion, Belinsky tried to talk to him seriously, but it was never fruitless. Each time, Lermontov used a joke or two to perfunctory, and then simply interrupted him, which embarrassed Belinsky.

"Lermontov is smart. It would be strange if anyone doubted that. "But I have never heard Lermontov say a reasonable, clever word. He seemed to be deliberately showing off the emptiness of high society. ”

Indeed, Lermontov always seems to flaunt this emptiness, sometimes adding a little Satanic or Byronic: a keen point of view, a vicious joke and a laugh, trying to show his contempt for life, and sometimes even the mood of a combatant to provoke trouble. There is no doubt that even if he did not portray himself as the protagonist of Lermontov's novel "Contemporary Heroes"), then at least this was an ideal character who disturbed him at the time and he was eager to emulate.

When he was imprisoned in the confinement cell after a duel with Barante, Belinsky visited him; he talked face-to-face with Lermontov for almost four hours, and then came straight to me.

I glanced at Belinsky and immediately saw that he was in a very happy mood. As I have already said, Belinsky does not hide his feelings and impressions, nor does he ever disguise them. He is the exact opposite of Lermontov in this respect.

"Do you know where I'm from?" Belinsky asked.

"From where?"

"I went to the confinement room to meet Lermontov and had a very successful conversation. He didn't have a single person there. Hey, man, for the first time I saw the true face of this man!! You know me: neither clever nor high-society. As soon as I got to him, I was immediately embarrassed, just like I usually do... To be honest, I felt very frustrated and decided to stay with him for a maximum of fifteen minutes. I felt uncomfortable for the first few minutes, but then we somehow talked about English literature and Walter Scott... 'I don't like Walter Scott,' Lermontov said to me, "his work is rarely poetic and dry." So he began to exert this insight, and the more he talked about it, the more he talked about it. I looked at him and couldn't believe my eyes and ears. The expression on his face became very natural, and he showed his true face at this moment... There was so much insight in his words, so profound and simple! It was the first time I saw the real Lermontov, and that has always been my wish. His topic shifted from Walter Scott to Cooper, and he spoke passionately about Cooper, arguing that the poetry in Cooper's work was much more than that of Walter Scott, and arguing very thoroughly and insightfully. Oh my goodness! How rich this man's beauty should be! What a delicate, sensitive poetic heart he had! ...... But he's a strange man! I think he's regretting it now, feeling that he shouldn't have exposed his truth, even for a moment— I'm sure of that..."

How can the concepts of Lermontov as an ordinary man and Lermontov as a writer be linked together?

As a writer, Lermontov was first and foremost astonished by his bold, astute, enterprising intellect: his worldview was much broader and deeper than Pushkin's—almost universally recognized. He offers us some works that show his great future. He aroused hope in people's hearts that he would not deceive him, and that if death had not caused him to shelve his pen prematurely, perhaps he would have come to the fore in the history of Russian literature... Why, then, do most people who know him think he is an empty man, almost a mere mundane man, and has a bad mind? At first glance, this may seem incomprehensible.

Yet most of those who know him are high-society people who see everything from a rash, narrow and superficial point of view, and some are shallow moral gentlemen who grasp only superficial phenomena and make arbitrary, conclusive conclusions about man on the basis of these superficial phenomena and deeds.

Lermontov was many times taller than the people around him, and he could not have taken such people seriously. It seems that what particularly displeased him was the latter group of people, namely the slow-headed upright gentlemen, who put on a posture of a very rational head, but in fact they were blind. It is abundantly clear that dressing up in front of these gentlemen as the most empty man, or even as a mischievous schoolboy, can bring about a certain spiritual enjoyment.

Of course, partly because of the prejudices of the circle in which Lermontov grew up and educated, and partly because of his youth, which gave rise to a desire to put on a Byronic coat and show off—factors that made many people with really serious thoughts feel very unpleasant, and also made Lermontov appear pretentious and repulsive. But can Lermontov be blamed for this? ...... He was so young when he died. When death forced him to put his pen down, he was engaged in a fierce struggle with himself in the depths of his heart, and as a result he might win, and instead associate with people with a simple attitude and establish a firm and firm faith...

<h3>03 Literature should be separated from the isolated artistic highs</h3>

Lermontov's work was published in the first few issues of the Chronicle of the Fatherland, which undoubtedly contributed greatly to the success of the journal, but a journal, no matter how well its literary column is, cannot develop without a comment column...

The literary and periodical publishing worlds in St. Petersburg were once attractive to me when I was on the sidelines, but as I got closer to them, this charm faded. When I rose behind the scenes of the literary scenes, I saw what a despicable human greed was motivated by those who I once worshipped as gods—vanity, money, jealousy... Belinsky's articles in The Telescope and The Group, Gogol's novels in Milgorod and Lermontov's poems began to expand my horizons slightly, to give me a new breath of life, and to give my heart a premonition that something better would emerge. Belinsky's essay began to shake my blind faith in some literary authorities and my cowardice toward them. From time to time I have pondered carefully the phenomena which have not aroused any thoughts in the past, and I have begun to observe people more attentively, to observe the real life around me, and I have begun to feel doubtful and uneasy in my heart; because of the stereotypes of my family and school, I have taken all kinds of life affairs for granted and have no objection to them since childhood, but now I seem unwilling to believe in these facts of life and accept them unconditionally. But all these signs of increasingly awakened consciousness are still very vague and very faint in my mind...

Art should serve itself, art is a separate, independent world, and the more indifferent the artist is in his work, or the more objective he is, as it was said at the time, the more noble he is—this idea was most prominent and prevalent in the literary world of the thirties. Pushkin developed this idea with his sonorous and harmonious poem, and in the poem "The Poet and the Gangster" it was used to an intolerable degree of egoism, but when we first recited the poem, we were overjoyed that it was almost Pushkin's best lyric poem. After Pushkin, all the eminent literary activists of the time and the youth who were active around them were dedicated and passionate defenders of art for art's sake.

Kukolnik is also an appreciator of this theory. We have seen that in the years before Pushkin's death, and especially after his death, he repeatedly preached that true art should not pay attention to everyday, contemporary, vulgar life, but that art should soar in the clouds, and that it could only depict heroic figures, historical figures and artists. This leads to the long and extremely tedious, cold inside, but enthusiastic depiction of the artist's drama and the huge, chiaroscuro contrasts between light and dark — and the more lengthy and tedious the play, the larger the base cloth of a painting, the more surprised the poet or painter. ...... Through these works, he fostered a very absurd self-confidence, as if the Russians could subdue the whole world without much effort, and this self-confidence later cost us dearly.

There is already a vague sense of the need for a new perspective in society, and a desire has been expressed that literature should be detached from the isolated altar of art and close to real life, and should be more or less concerned with social interests. The bombastic artists and protagonists bore everyone extremely bored.

What we want to see are ordinary people, especially Russians. At such a moment, Gogol suddenly appeared, and Pushkin was the first to see his great talent with his artistic discernment, but Bollevoy did not understand him at all, and at that time everyone still regarded Boljevoy as an advanced figure.

Gogol's Chancellor of Chincha was a great success, but in the beginning, no one, even among Gogol's most ardent admirers, fully understood the significance of the work, nor did they foresee how significant a change the author of the comedy would bring. Kukolnik only responded with a sneering laugh after watching the performance of "The Chancellor of Chincha", he did not deny Gogol's talent, but at the same time said: "This is only a farce after all, not an art." ”

After Gogol came Lermontov. With his sharp and bold commentaries, Belinsky infuriated the literary aristocracy and the outdated literary scholars, but fascinated the new generation.

A breath of fresh air has blown into the literary world...

The excerpt of this article is selected from the eighth chapter of the book "The Age of The Brilliant Stars", which has been deleted from the original text, and the subtitle is the editor's own draft, and it is published with the authorization of the publishing house.