The taking of the character of Ruan Ming in "Camel Xiangzi" has always been a puzzling topic. First of all, he is an indispensable and important character in the work, which influences the direction of Shoko's life for a long time; at the same time, he seems to be a dispensable character, and after the 1955 People's Literature edition of "Camel Xiangzi" completely eliminated this character, the plot of the novel is still coherent.

Regarding this strange phenomenon that has been ignored for many years, in my limited reading horizon, Professor Wu Yongping of the Hubei Academy of Social Sciences gave a very valuable interpretation evidence in his paper "Camel Xiangzi: Unfinished Ideas: Text Perusal and Cultural Sociological Analysis" (Jianghan Forum, No. 11, 2003). He introduced the historical facts of the 1929 Beiping Yang coachman riot, believing that the lack of the key plot of the foreign coachman riot, which did not have time to be written into the novel "Camel Xiangzi", "led to ambiguity in the ideological connotation of the work".

As we all know, Lao She's novel creation adheres to the literary tradition of realism, especially in the works depicting the low-level citizens of Beijing, it is even more exquisite to the seasons, geography, folklore, etc., no matter how big or small, as fine and accurate as line drawing. That being the case, it is highly doubtful why "Camel Xiangzi", a work about the life of Peking coachmen in the late 1920s, did not write about the huge coachman riots in 1929. What's more, Lao She once made it clear in his work that he was aware of the coachman's rebellion: the short story "Black and White Lee", written before "Camel Xiangzi", was written entirely based on this riot as the prototype event. Wu Yongping's paper, cited above, also raises this confusion. I believe that readers who are familiar with "Camel Xiangzi" and know about the 1929 Peking Coachman Rebellion will have the same confusion.

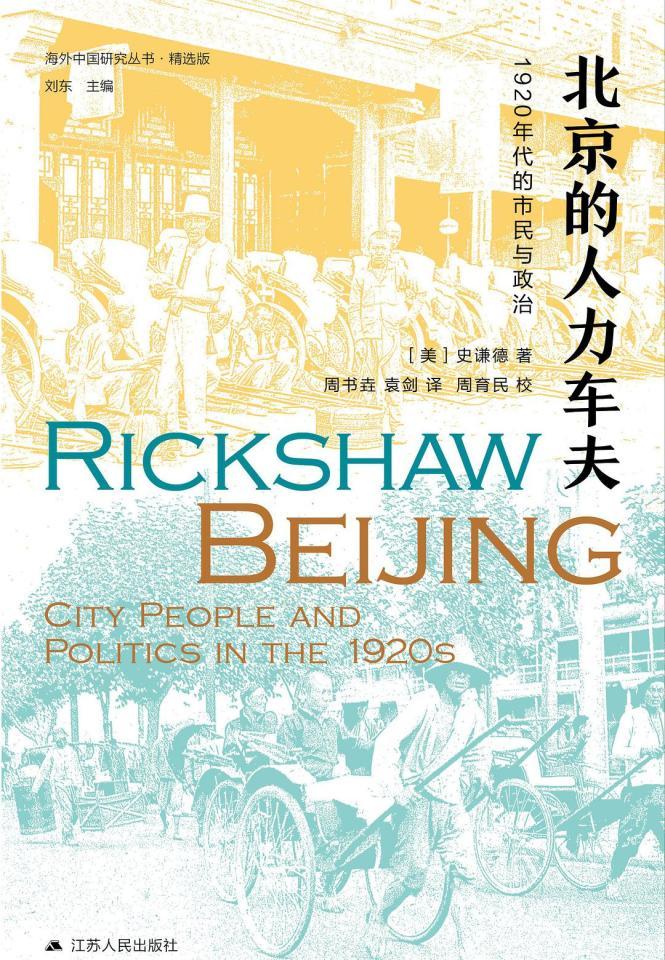

Recently, I read the American literary historian David Strand's "Rickshaw Beijing: City People and Politics in the 1920s, translated by Zhou Shuyao and Yuan Jian, Zhou Yumin School, Jiangsu People's Publishing House, the first edition in October 2021), on this issue.

"The Rickshaw Driver in Beijing: Citizens and Politics in the 1920s", by Shi Qiande, translated by Yuan Jian, Zhou Shuyao and Zhou Yumin, published by Jiangsu People's Publishing House in September 2021, 392 pages, 88.00 yuan

One

"The Rickshaw Pullman of Beijing - Citizens and Politics in the 1920s" (below the subtitle) was first published in 1989, according to the proofreader Zhou Yumin's "Afterword", the book was basically completed in 2014, and it was only now officially released Chinese edition, which is also out of various helplessness; making trade-offs and integrations in the translations of the two translators will inevitably increase the loss of a certain translation. However, in any case, this book is finally published, and we can finally straighten out the relationship between Xiangzi, Wang Wu, Ruan Ming, Bai Li Yiganren and the 1929 Peking Coachman Rebellion, which is still a gratifying harvest.

This is a long-awaited book of details related to modern Chinese history. Because the "coachman" group is one of the earliest citizens to enter modern Chinese literature, it is also a long-awaited historical reference book related to modern Chinese literature. As a historical monograph, before the exhibition, I intuitively felt that the book might list various data and documentary evidence and be relatively boring; after the cover-up, the strongest impression was that the book made the life in Beijing (/Beiping) nearly a hundred years ago because of the detailed display of the book, especially the laying out of the 1929 coachman riot incident, not hurried, telling the story, and the climax, which was beautiful.

Little is known about the 1929 Peking Coachman Rebellion, which should have been included in the field of 1929 as an important interpretation clue for Lao She's important works such as "Camel Xiangzi" and "Black and White Li". On this point, Wu Yongping said:

Fan Jun's article "On the Realism of "Camel Xiangzi"" is accurate in grasping the chronology reflected in the work, but he does not take into account the historical events of the "riot" of the foreign coachman; while Sun Yongzhi's "New Evidence of the Age Reflected by the Camel Xiangzi" believes that the age reflected in the work should be from the spring of 1928 to the autumn of 1931, and completely regards the "riot" of the foreign coachman as a fiction of the novel.

(Wu Yongping, "'Camel Xiangzi': Unfinished Ideas: Text Perusal and Cultural Sociological Analysis", Jianghan Forum, No. 11, 2003; Fan Jun: "On the Realism of 'Camel Xiangzi'", Literary Review, No. 1, 1979; Sun Yongzhi: "The New Chronological Evidence Reflected by 'Camel Xiangzi'", Literary Review, No. 5, 1980)

Sydney Gambaugh photographs a rickshaw puller in Beijing

Two

So, what happened to the Peking Coachman Riots in 1929? The Rickshaw Driver in Beijing has a special chapter detailing the ins and outs of the incident (see Chapter 11 of the book, "The Machine Destroyer: The October 22, 1929" Car Boom). The reason for the riot is just like the simple cognition of the coachman Wang Wu in the novel "Black and White Lee": "Do you know that the tramway is almost finished?" As soon as the tram opened, we finished pulling the car! Schiend summarized the riots that culminated in October 22, 1929, as "tens of thousands of rickshaw pullers who premeditated attacks on the tram system and became machine destroyers." (277 pages)

The riot underwent protracted brewing, the seeds of collective opposition to the machine had been planted in the spring of the same year, fueled by the pseudo-federation of trade unions, during which several clashes between peasants, monks, engineering team workers and tram workers were triggered, and finally the ultimate confrontation and the greatest destructive force were reached among the groups of coachmen who had the deepest grievances and the greatest hidden dangers with the tram workers. As a result of the driver's rebellion, sixty of the company's ninety trams were destroyed, and the leader of the riot side, Zhang Yinqing, fled, but his cousin Chen Zixiu and three other union leaders were shot at the Tianqiao execution ground. (pp. 314-316)

From the above historical facts, it is not difficult for us to see the prototype of the story of white Lee escaping and black Lee killing in "Black and White Lee". Shi Qiande also made a natural analogy:

...... This younger brother of a radical, who is old and sophisticated, close to poor workers, has a cunning and cold appearance, and has the ability to deceive executioners, which is very similar to Zhang Yinqing's personality. (321 pages)

Therefore, we have reason to believe that although Lao She eventually evolved the story of the two riot leaders who died and fled into the tragic story of Li Daitao in the style of "A Tale of Two Cities", we can still see the strong intertextuality between it and the 1929 Peking Coachman Rebellion from the plot direction and character relationship of "Black and White Lee". We also know that although "Black and White Lee" was written in 1933, it was born out of "Daming Lake", which was destroyed by the cannon fire of the Songhu War in January 1932. So there is only one truth: Lao She learned the basic facts of the 1929 Coachman Riot early on, and tried to write this incident into the novel, which led to the death of Black Li in "Black and White Lee" and ruan Ming in "Camel Xiangzi".

Three

The above events allow us to focus on a name that is still quite unfamiliar to the study of modern Chinese literature: Zhang Yinqing.

Zhang Yinqing was the head of the Beiping Federation of Trade Unions, which was founded in July 1928. In December 1928, the Beiping Municipal Party Department removed the party members, and Zhang Yinqing was demoted to the director of the Leather Pants Hutong Civilian Art Factory, but in fact still controlled a considerable part of the trade union (Du Lihong: "The Beiping Labor Tide in the Early Period of the National Government in Nanjing and the Transformation of the Kuomintang", Modern History Research, No. 5, 2016). As mentioned above, the 1929 Beiping Rickshaw Pullman Rebellion was planned by Zhang Yinqing and organized by his cousin Chen Zixiu.

When the question of Zhang Yinqing and He Xuren also surfaced, we were one step closer to accurately interpreting Lao She's "Black and White Lee" and "Camel Xiangzi", two novels with foreign coachmen as the main writers and stories in the 1920s.

Lao She once said that when he wrote "Daming Lake", he wrote "many ×× and ..." ("How I Write "Daming Lake"), and we usually think that this "×× and ..." refers to the sentences that were forbidden in the era of white terror (to reiterate that these contents were destroyed by the "One/ Twenty-Eight" war, and Lao She later perfunctorily took this part of the content into "Black and White Lee"); combined with the isomorphic relationship between "Black and White Lee" and "Camel Xiangzi", we take it for granted that these contents became Ruan Ming in "Camel Xiangzi"" It was further fermented when he participated in the work of organizing the foreign coachmen" ("Camel Shoko", para. 24), which constituted what must be deleted when it was republished in 1955.

Now we have finally restored the prototype of Bai Li/Ruan Ming to Zhang Yinqing, at this time, we found that there was a huge dislocation hidden here. Because when Zhang Yinqing launched the Coachman's Rebellion, it was at the lowest tide of our Party's revolution after the "April 12" counter-revolutionary coup, and whether it was the Federation of Trade Unions itself or the Coachman's Rebellion, including the various demonstrations before the Coachman's Rebellion, it was basically launched by the Kuomintang in power, and it was a series of events that occurred in the process of infighting among the Kuomintang factions. (Zhuang Shanman's April 2007 master's thesis, "A Study of the 1929 Rickshaw Pullers' Trend in Beiping," p. 15: "As Zhang Yinwu said in a press reception on October 24, 1929, 'the motive was the overthrow of the old and new factions in the party, and the result was that the rickshaw drivers destroyed the trams.'" Pages 315-316 of The Rickshaw Puller in Beijing: "The pro-Nanjing Party believes that Zhang Yinqing and his henchmen conspired to plan the riot. At this moment, is the true face of Bai Li/Nguyen Minh wrapped in the ambiguity of "revolution" clearer?

But there is another problem here, and it must be pointed out by the way, that is, whether it is the criticism of Nguyen Minh from the left in the 1940s and 1950s, or the drastic deletion of Nguyen Minh in the 1955 people's literature edition of "Camel Xiangzi" after Lao She himself accepted this criticism, it all points to the same misreading. As for what Lao She himself thought at first, whether he knew that Ruan Ming's prototype Zhang Yinqing was originally a city scoundrel, he did not say; because the novel itself certainly allows the reintegrate of the archetypal events from the author's point of view, we have no way to speculate.