In October 2016, in the face of the upcoming Big Billion Days Sale, employees of Indian e-commerce platform Flipkart rushed to prepare for it. The conference room at the headquarters in Bangalore was also renamed the "War Room". Employees sometimes wake up from their beds or lazy couches for days on end to complete app redesigns, stress test systems, and make last-minute blasty calls with brands, sellers, and warehouse workers.

2016 was undoubtedly a pivotal year for Flipkart. As a valuable startup in India, Flipkart's series of missteps allowed Amazon, the overseas retail giant in the Indian market at the time, to catch up.

As the sales season approaches, everyone is watching the battle closely – Amazon and Flipkart are running big promotions at the same time. Investors, analysts and executives in the e-commerce industry believe Amazon's victory could kick-start Flipkart's irreversible decline.

In an effort to turn the tide, Flipkart's investors went against the founder's wishes by parachuting an executive, Kalyan Krishnamurthy, four months before the sale. He was given broad terms of reference and needed to carry out an urgent order - to defeat Amazon.

"2016 was more of a war for us." Krishnamurthy, now CEO of the Flipkart Group, said in a recent interview.

Krishnamurthy's sales strategy is also simple: go all out on the smartphone track, the company provides interest-free loans to consumers, and Krishnamurthy even personally visits mobile phone brands to reach exclusive sales agreements. A Flipkart executive who worked with him at the time recalled begging a phone maker to "give him a chance."

Sure enough, his strategy worked. Data from market research firm RedSeer shows that in terms of total value of goods (GMV), Flipkart achieved 50% market share during the promotion, compared to Amazon's 32%.

This makes Amazon sit still.

A former executive at Amazon's payments business said that within the company, some leaders still believe they missed the opportunity to kill Flipkart. Despite its success, Flipkart did not get out of the woods and continued to suffer huge losses. If you want to stay ahead of Amazon, you need to keep injecting new capital into yourself.

Luckily, Flipkart piqued the interest of another American retail giant.

01 In the midst of doubts, the capital frequently favors it

U.S. retail giant Walmart has been looking for a foothold in the Indian retail market for some time and has previously discussed its willingness to invest in Flipkart. Later, Walmart considered acquiring it. In May 2018, after more than half a year of negotiations, Walmart agreed to pay $16 billion to acquire a 77% stake in Flipkart. It was Walmart's biggest deal ever.

Analysts generally see the acquisition as a risky attempt on the grounds that Walmart, which has not yet tasted success in the e-commerce industry, is shelling out a huge sum of money for a potentially unprofitable company in a tough market regulatory environment. As a result, on the day of the announcement, Walmart's stock price fell 3%.

Abhishek Goyal, a former executive at Accel Partners and one of Flipkart's earliest backers, has said that Walmart paid "sky-high" for Flipkart, but it was a deal they "had to do." Amazon has also been showing interest in acquiring its competitors.

"If Amazon buys Flipkart, Walmart will be in trouble because there are no such assets in the world to resupply." He said.

Nearly five years later, Walmart's bets have been revived — Flipkart has nearly doubled in value and secured its position at the top of the market. At the same time, despite the company's desire to go public, it is still far from profitable, and the expansion of online shopping platforms in India has failed to maintain the pace of the pandemic. At the same time, competition from local groups enjoying government support is intensifying.

In fact, Flipkart has been inextricably linked to Amazon from the beginning. Flipkart's founders, Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, worked in Amazon's India office in the mid-2000s. When Amazon decided not to launch an e-commerce service in the country, they, like many of their colleagues, left to start their own businesses. In 2007, they founded Flipkart based on Amazon.

Initially, Bansal faced skeptical investors. Goyal, co-founder of financial data platform Tracxn Technologies, believes that engineers like Bansals are not suitable for running complex retail businesses, and that e-commerce is not viable in the Indian market for the following reasons. The country lacks good road conditions, suitable warehouse operations, and trained delivery drivers. It is widely accepted that it takes fifteen years to set up a large e-commerce business, not five to six years.

Meanwhile, Lee Fixel, a young fund manager at U.S. investment firm Tiger Global, saw an opportunity at Flipkart to expand his firm's portfolio in India. Unable to find another way to get in touch, Fixel called Flipkart's customer support line. Flipkart founder Bansals initially thought it was just a hoax.

Eventually, after an acquaintance, Fixel agreed to invest $10 million to fuel Flipkart's explosive growth. With its English-language website, Flipkart targets young, affluent urban groups. Superior customer service and a more reliable delivery system have enabled the startup to beat local challengers. Official Indian documents show that Flipkart's main brick-and-mortar store sales quadrupled in the first full fiscal year following Fixel's investment.

02 The intensifying e-commerce war

Amazon also took notice of Flipkart's rise, making its first attempt to acquire the startup in 2011, but was deterred by Flipkart's founder's bid.

Amazon also launched its own India site in 2013, which then-CEO Jeff Bezos made at the top of its list. According to a former executive at Amazon's India team, Bezos asked his team to go ahead without worrying about burning money. Amazon lost ground in China, but Bezos seemed reluctant to let another billion potential consumers slip through his fingers.

On July 29, 2014, Flipkart raised a record $1 billion, a record high in India – an event that also fueled an unprecedented funding boom for Indian startups. Then-CEO Sachin Bansal predicted that his business also generated $1 billion in annual GMV a few months ago and would grow rapidly.

"We believe India can have a $100 billion company in the next five years, and we want to be like that." He said at a news conference.

Few find this ambition unbelievable. If China can produce giants like Alibaba and JD.com, why can't India? A day later, Bezos raised the ante, promising Amazon would invest $2 billion to expand its India operations.

It was also during this time that Flipkart went awry, according to an executive who requested anonymity at the time, that Flipkart went awry, and they signed a nondisclosure agreement. Sachin Bansal, obsessed with transforming Flipkart from a retailer to a tech company, cut back on internal logistics and shifted resources from website building to apps, but both proved costly mistakes.

In January 2016, Binny Bansal replaced Sachin Bansal as CEO of Flipkart, but he couldn't stop the decline. According to media reports based on the company's internal data, Amazon briefly surpassed Flipkart in GMV in mid-2016.

Tiger Global's Fixel stepped in and put Krishnamurthy in the role of head of Flipkart's category design organization.

It proved to be a successful move.

Krishnamurthy grew rapidly in Flipkart. By 2017, in addition to its eponymous e-commerce platform, Flipkart owned fashion retail sites Myntra and Jabong, as well as a payment app, PhonePe. In January of the same year, Binny Bansal became Group CEO and Krishnamurthy was appointed CEO of Flipkart, a valuable asset, for his performance in Big Billion Days. Although he still needs to report to Bansal, the board has given him a lot of autonomy.

Krishnamurthy began reinventing the company in his style. He quickly ousted most of the big-name leaders hired by Bansal and handed over power to managers he had mentored. In addition, according to a former Flipkart executive, he began pushing Flipkart to compete fiercely with his own subsidiary, Myntra, to prove that he should control all of the Flipkart Group's e-commerce assets.

Among the changes, Sachin Bansal also left Flipkart. Sachin Bansal, who was executive chairman at the time and led negotiations with Walmart and Amazon, left the company abruptly in May 2018 just as the Walmart deal was being finalized. According to several Flipkart executives, he had wanted to become group CEO after the acquisition, but Flipkart's board backed Krishnamurthy. Sachin Bansal was eliminated from the game and netted about $1 billion from his 5.5 percent stake.

Months later, Binny Bansal resigned after an internal investigation into an "aggravated personal misconduct" charge related to alleged incidents that Bansal had not disclosed during negotiations with Walmart. Nervous Walmart executives asked Krishnamurthy to take over as group CEO, adding fashion sites Myntra and Jabong to his area of responsibility.

Krishnamurthy said the acquisition by Walmart was the smartest thing Flipkart has done in the past decade.

"Startups are in the early stages of development and need to be constantly funded," he said. Meanwhile, Walmart's ownership has stabilized Flipkart's position without sacrificing its innovative edge.

"Over time, we've made our business more sustainable and predictable." He said.

03 Flipkart after the change of owners

As an independent startup, Flipkart has been focused on rapid expansion. Walmart denied the failure of a previously Indian company after being accused of violating investment laws and mismanagement, ensuring that the company continued to grow on track, and then immediately set about strengthening Flipkart's finance, legal and accounting departments and investing in a large compliance team.

In 2020, a former executive recalled, Flipkart wanted to launch health products and services, but the investment committee, made up of senior Walmart leaders, refused to approve them because of unclear regulations. In 2021, Flipkart finally announced the launch of its Flipkart Health+ program.

"I wouldn't say we didn't worry about the law before, but under Walmart, our risk appetite has decreased." The former executive said.

Overall, Walmart has little involvement in Flipkart's logistics, sales and technology departments. According to two consultants who have worked with Flipkart, Krishnamurthy rejected Walmart's proposal to hire more accomplished executives, stepped down some key leadership positions, such as chief commercial officer and chief operating officer, and ran Flipkart with a lean, low-key management team.

According to former employees, Krishnamurthy's favorite approach is to delegate new projects and key operations to younger managers and set high-growth goals for them to play freely. The employees said that because he cared less about rank, he often bypassed the senior vice president to interact directly with the managers who oversaw the company's day-to-day operations, and regularly shuffled and promoted them.

Krishnamurthy's leadership style has also earned him the respect and loyalty of his employees – and unshakable control over the company. Meena, the company's e-commerce consultant, said Walmart gave Krishnamurthy a high degree of autonomy in running Flipkart. However, Flipkart did not respond to a request for comment on Krishnamurthy's management style at the company. Walmart also did not respond to a request for comment.

Three former executives who worked closely with Krishnamurthy said Krishnamurthy's prominence also risks making the company overly dependent on him and lacking potential replacements. Meena said that like many large Indian internet companies, Flipkart has no deputy who can replace Krishnamurthy.

04 Flipkart's survival

In the city of Corral, northeast of Bangalore, stands one of the largest warehouses in Flipkart, covering an area of about 6 football fields. Such warehouses have been key to Flipkart's strategy from the start, meaning that the company can guarantee on-time deliveries, giving them an edge over competitors who outsource logistics.

Today, control of the supply chain continues to give Flipkart and Amazon an edge. There is little difference between the two companies in terms of products and services. Analysts say Amazon leads in larger cities in India, while Flipkart is more popular elsewhere. According to research firm Bernstein, Flipkart's GMV, including that of its Myntra fashion platform, reached $23 billion in 2021, while Amazon's GMV was around $18 to $20 billion.

Bernstein and Meena attribute much of Flipkart's continued success to its one-and-two punch in fashion, which Amazon has so far failed to contend with. Flipkart focuses on basic clothing, accessories, and brand discounts, while Myntra attracts more fashion-conscious consumers. Bernstein and other analysts estimate that Flipkart and Myntra already monopolize about 60 percent of India's online fashion market.

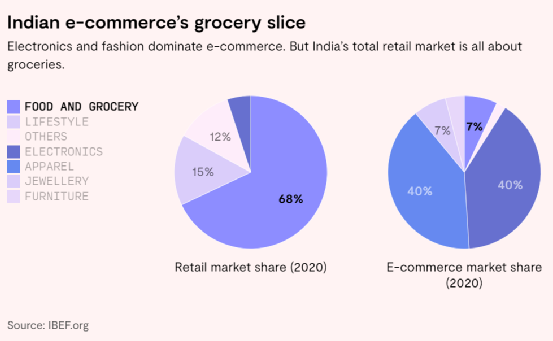

Flipkart has also experimented in other areas, acquiring online pharmacy platform SastaSundar and travel app Cleartrip in 2021, both of which offer the services Amazon is offering. But Krishnamurthy's biggest bet is the key to India's e-commerce — the grocery category.

Until 2020, Flipkart offered grocery and convenience store merchandise in a handful of cities. In 2022, the company expanded its services to 1,800 cities, covering more than half of the country. The category, although currently small, is considered essential for the future of the company, so much so that in May 2022, the company divided its application into two sections: groceries and other products.

Source/ IBEF.org

As the grocery business continues to grow, Flipkart's prospects hinge on its operational ability to increase the number of regulars. Both Flipkart and Amazon claim to have about 1 billion app downloads. At the same time, India has more than 800 million internet users, and these companies seem to have huge growth potential.

In fact, users outside of big cities are rarely used to online shopping, in part because of their lack of trust in online platforms – cash on delivery is still more popular than online payments. Jeyandran Venugopal, chief product and technology officer at Flipkart, said the company is aware that there are barriers to trust and platform access for the next 300 million to 500 million users.

Over the past three years, Flipkart has launched a series of initiatives to attract these users, including a new app called Shopsy, which offers ultra-low-priced products from small sellers — watches for $1.50 and shirts for $3. The company also offers its app in 11 Indian regional languages and has machine-translated reviews originally written in English.

E-commerce consultant Meena said that most of Flipkart and Amazon's business still comes from urban consumers, and it may still take the next three to four years for the number of online consumers to reach 100 million.

Meanwhile, Flipkart continues to defend its e-commerce crown, but one of its biggest rivals may not come from its peers, but from the Indian government. As part of a broader push for Hindu nationalism, Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed support for homegrown businesses in certain sectors. Even before it was acquired by Walmart, some government officials and bureaucrats viewed Flipkart as a foreigner-owned business, not a homegrown company.

In 2019, the Indian government imposed a series of restrictions on foreign online retailers, including a ban on exclusive brand collaboration. Flipkart, Amazon and similar platforms have previously found ways to circumvent earlier regulations by building close relationships with some of the major sellers, building complex corporate structures, adjusting commission rates and other mechanisms to support partner discounts.

But their troubles are far from over. In January 2020, India's antitrust regulator announced an investigation into Amazon and Flipkart, which is still ongoing.

Against this backdrop, Indian competitors have been eager to take advantage of the favorable environment for domestic e-commerce platforms. India's two largest conglomerates, Reliance Industries and Tata Group, are both working to break the monopoly of two e-commerce oligarchs, Flipkart and Amazon.

Abhishek Maiti, director of research firm PGA Labs, estimates that Flipkart and Amazon together control about 70 percent of India's e-commerce market share, about the same figure as four years ago.

Goyal, a former Accel Partners investor, said PhonePe, the payments app in which Walmart has a stake, has always been a "savior-like presence." PhonePe is already well ahead of Google Pay as the largest app on India's major digital payment networks. PhonePe was completely separated from Flipkart in December 2022, in part to position itself as a "homegrown" company run by Indian entrepreneurs and conduct an independent IPO, of which Walmart remains the majority shareholder. A funding round in January valued PhonePe at more than $12 billion, signaling a huge gain on Walmart's books.

Since the end of 2020, Reuters and Indian newspapers have reported that Flipkart is in the process of an IPO. According to two people involved in the preparations, the company wants to list in the United States and has begun taking measures under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which regulates public companies in the United States. But they say Flipkart isn't ready to go public.

Krishnamurthy has said the company has discussed an IPO with its board, but they have not yet proposed a specific timing for it. In July 2021, Flipkart raised $3.6 billion in financing, which at the time was valued at $37.6 billion, about one-tenth of Walmart's current market capitalization.

While Flipkart is ahead of Amazon in terms of market share, official Indian documents show that its losses have soared since striking deals with Walmart, and the outlook for the broader e-commerce market is uncertain. According to PGA Labs, e-commerce in India grew at an impressive 35% rate in the fiscal year ending March 2022 due to the pandemic. Inflation is dampening spending as India's economic growth slows, forecasts say. In India, e-commerce share remains a single-digit percentage of the total retail market share, compared to 14% in the US and 24.5% in China. The slowdown in early-stage growth, if not reversed soon, could hurt Flipkart's valuation and prospects.

Krishnamurthy said the Flipkart craze has subsided, but the overall trend looks solid. During the pandemic, he believes that everyone thinks that e-commerce growth has suddenly accelerated significantly, but it is actually partially exaggerated. Over the past four to five years, e-commerce in India has continued to grow slowly but steadily. There is no negative trend change, which is actually a positive trend change.

In January 2023, the Economic Times, an Indian newspaper, reported that Walmart planned to buy about $1.5 billion worth of shares from a handful of Flipkart investors, further increasing its stake in the company.

Cover/Figureworm Creative