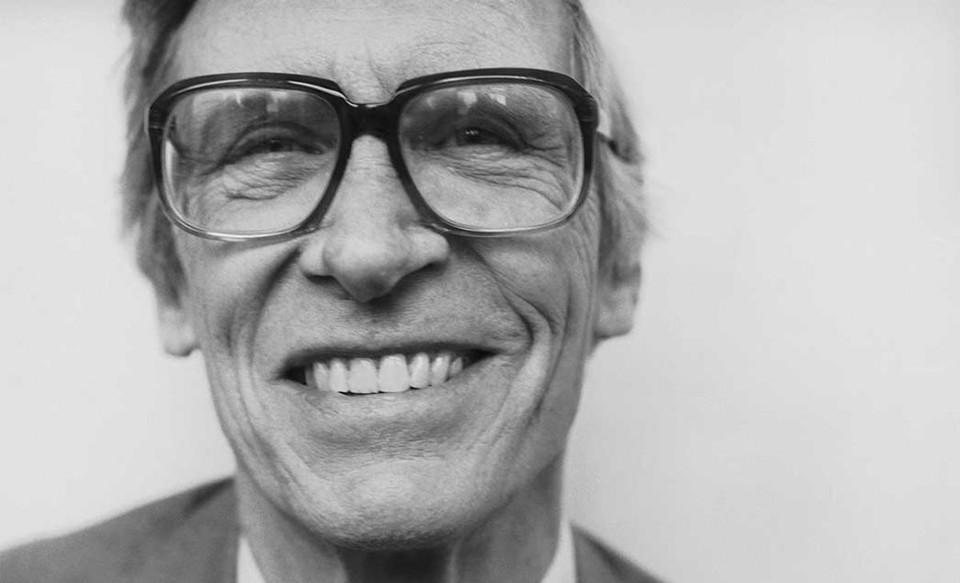

Rawls (above), one of the most famous political philosophers of the twentieth century, was humble to Kant like a schoolboy.

What is a classic? Philosophers, intellectuals, and university teachers usually tell us that the classics are the great works left by great thinkers, the essence of the legacy of human thought that we cannot bypass or miss in our lifetime. Therefore, classic works are often included in the required reading lists of university teachers. A few years ago, the Quartz website published a list of required reading books for top U.S. universities. The top ten required reading items are: 1. Plato's "Republic"; 2. Hobbes's "Leviathan"; 3. Machiavelli's "Monarch"; 4. Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations and the Reconstruction of World Order"; 5. Strönck's "Elements of Style"; 6. Aristotle's "Nicomachean Ethics"; 7. Kuhn's "Structure of the Scientific Revolution"; 8. Tocqueville's "On Democracy in America"; 9. Marx's "Communist Manifesto"; 10. Aristotle's "Political Science". In addition to the fifth-ranked English writing tool book", "Elements of Style", the other nine are all classics of humanities and social sciences.

However, the impression of ordinary people is that the classics are those heavenly books that must be read but do not want to read, and even if they read, they read in vain. Why? First, the classics are not easy to read. Most of these books are old and have little direct relevance to our time, and we do not have sufficient background knowledge of those distant pasts, so it is often difficult for us to enter the context of their texts and the context of the times. We don't necessarily know what questions the author is trying to answer, and how important the questions the author wants to answer are. It is in this way that we wonder if our IQ is so low that we can't even read it. Second, the classics cannot be read. Even if we make great efforts to read these classics in peace and quiet, we may enter the treasure mountain and return empty-handed. These books are often obscure, there may be multiple interpretations in a sentence, and it is difficult for scholars to give accurate conclusions, so beginners are often discouraged. Third, classics are not practical. Even if we understand it, we still feel that these days the book is useless, and it is a waste of time to read or not to read a sample. We can certainly console ourselves by saying that we are relentlessly pursuing "free and useless souls." However, the souls of our ordinary people are often settled on the chai rice oil and salt, and we have to ask: Can reading these books help me find a job? Can you help me with three meals a day? Can you help me repay the loan?

So, how should we read the classics that cannot touch the heart?

The attitude of reading the classics should be humble, not arrogant. Just because we cannot understand the classics, we cannot assume that the classics are fallacies and heresies and nonsense. Let's also look at how Rawls, the greatest political philosopher of the twentieth century, read the classics: "I always take it for granted that the thinkers we study are much smarter than I am. Otherwise, why would I waste my time with my students studying them? If I see an error in their argument, I assume that the thinkers themselves have seen it, and must have dealt with it. But where? What I'm looking for is their way of thinking about solving the problem, not my own. Sometimes their thinking is historical: in their time, the issue did not need to be raised, or had not yet been raised, and therefore could not be fully discussed at that time. Or maybe I've overlooked or haven't read a part of the text yet. I assume they never make obvious mistakes, at least not major ones. ”(John Rawls, “Afterword: A Reminiscence,” in Juliet Floyd and Sanford Shieh (eds.), Future Pasts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 427.)

About a decade ago, when I was visiting Harvard, I consulted the Rawls Archives of Harvard University, which contained Rawls's collection of books from his lifetime. Rawls has a collection of four of Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, one in German and three in English, and three identical. Why did he buy three identical books? Because the other two books had already been read by him, he made a lot of side comments in the book with several different colored pens. When I saw these books, I really couldn't believe it, and I couldn't imagine how many times he had read them like this. Rawls is recognized as the greatest political philosopher of the twentieth century. In front of Kant, he was humble like a schoolboy, listening respectfully to Kant's teachings, listening to lectures and taking notes at the same time, and he took seriously the ideological legacy of his predecessors with a learning mentality.

My friend Professor Zhou Baosong, who is famous for his research on Rawls Chinese academia, once recounted a similar experience of his. When he was a student, he listened to G. Curchen at Oxford University. A. Cohen) in a class, he said: "On the first day of class, I sat next to Cohen and saw on his desk a copy of The Theory of Justice, the first Oxford edition, and the writing was in tatters. He carefully opened the book, and I saw that the six-hundred-page book was completely scattered, the book was not a book, and each page was densely packed with notes. At that moment I was stunned, and I knew that the book should be read like this. At that time, I thought that even Ke Heng, a philosophical person of the contemporary analytical Marxist school, should study the "Theory of Justice" with such an attitude, how could I not do it?! (See The Politics of Equality of Free People, Second Edition, Beijing Sanlian Bookstore, 2017, pp. 302-303.) )

A classic without activation is not a classic. Classics are hard to read because we didn't activate classics. If the classic is not activated, then the classic is not our classic, but someone else's classic, which for us is equivalent to a pile of useless waste paper. So, how do you activate Classic? I personally think there are two ways to do it. The first is to restore the context of the author's time to activate. If we are to truly understand Plato's Republic, we are required to understand the background of the Republic. For example, who was Plato? What is his upbringing and personality traits? Why did Plato write in a dramatic way? When was Republic created? What was the social, political, and economic situation in Greece when Plato wrote the Republic? Are the characters in "Republic" really have their own people, what is the background of the lives of those people, and are there any discrepancies with the personality characteristics of the people in the play? We can't read The Republic in large part because we lack this background knowledge. The more background knowledge you have, the more likely you are to read it.

The second is to activate the classics with the reader's sense of the problem. Readers do not blindly read the classics for the sake of reading the classics, but read the classics with questions, and the reading feeling is completely different. You have confusion in your heart, you have thoughts, you have ideas, and you hope to answer the confusion in your heart from the classic reading, and respond to what you think in your heart. In this way, when the question discussed by the author and the problem that the reader is thinking about meets, the two will collide with each other. If you are particularly concerned with the issue of educational equity, you will wonder whether plato's approach to education promotes educational equity. If you are particularly concerned about the status of women, you will worry about the situation of women in the Republic. You activate the problem consciousness of the Republic with your problem awareness.

After activating the classics, we also need important second-hand literature to assist us in reading, which is the best way to get started with the classics. Many scholars have spent a lifetime of painstaking study of one or two classics, and the interpretations they have written are undoubtedly the best guides for us to enter the world of classics. If you can't understand Aristophanes's Clouds, try reading Rhetoric, Comedy, and the Violence of Language in Aristophanes' Clouds, which is a book that sorts out and explains the entire structure of the play in the order of the text of The Cloud, making it very convenient for us to grasp the textual context of the Cloud. Classic works in the history of Western thought basically have similar guides, such as the Routledge Philosophy Guidebook series. Reading Plato's Republic can be accompanied by Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Plato and the Republic, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics can be paired with a Philosophy Guidebook to Aristotle on Ethics, and Locke's Treatise on Government can be paired with Routledge philosophy guidebook to Locke on government, Rousseau's Social Contract can be paired with Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Rousseau and The Social Contract. This set of books is also characterized by the gradual combing of the classical logical structure according to the order of the texts. Reading alone may end up with half the effort; and this kind of reference book to assist reading may be more effective with half the effort.

If you study alone and have no friends, you are lonely and unheard, so you may wish to organize a reading club to read the classics together. I personally recommend that book clubs do not take the approach of reading in advance + live discussion. In my previous experience of organizing book clubs, this book club model is often unsustainable. At the beginning, everyone will read carefully, after reading a few times, many people simply do not read, directly come to the scene to listen, and finally even do not come. The book club mode I recommend is that the live takes turns reading word by word, then combing through the text structure and discussing difficult issues. The advantage of this approach is that people can come to the book club without burden. Read in advance, and you may have forgotten a lot of important content after coming to the scene. Live reading, all feelings are alive, there will be no problem of forgetting. Moreover, the participants in the book club should preferably be peers of similar level. If there is a teacher or a specialized researcher who is intellectually enough to crush others, the end result is that the book will become a lecture. He said that others listened, and there was simply no equal opportunity for discussion. No discussion is equal to no participation.

If you exhaust the above methods and still can't read those classics, or have no feeling for those heavenly books, then give up. No book has to be read. Someone once asked me, if I can't read the classics, what should I do? My answer was, "If you can't read it, you can stop reading it." Books and people also pay attention to fate. Although some books are classic, the problems they study are not your concerns, and you may not be able to enter the inner path of these books. In the future, when your research is carried out to a certain extent, your problem awareness and the problem awareness of these books have a certain overlap, and perhaps you will suddenly be enlightened. Frankly, I also read the Dialectics of Enlightenment a few years ago, and I didn't know German, so I read the English version first, completely unaware. Then, I looked for Chinese book to compare, or I didn't know what to do. Later, I was directly shelved. I thought in a few years to finish my research and start really studying the enlightenment problem, and I would read it again. Another example is Habermas's "Crisis of Legalization", which I do not know. Many classics are not related to me. I was frustrated at first, and then I figured it out. In fact, everyone has three or four classics in their hearts, and these three or four classics, you have to read them repeatedly and become familiar with them. In the future, every time you think about a problem, you can get inspiration and inspiration from these three or four classics. So, what you're looking for is these three or four classics. These three or four classics, when you look at them, you have a sense of seeing each other and hating the evening, and you can't put them down when you pick them up, and many of them hit your heart. You think in your heart, this is what I've been thinking about, this is where my confusion lies. As for the other classics, they may not be your dish, and they will be waiting for the next day. I'm not afraid of your jokes, and so far I haven't turned over Kant's three major criticisms. Because the problem he studied was not one of concern to me. But one day my question is linked to his question, and I will be eager to open his book. That's my idea. ”

Marwalin