The sky is boundless, and the thoughts are endless.

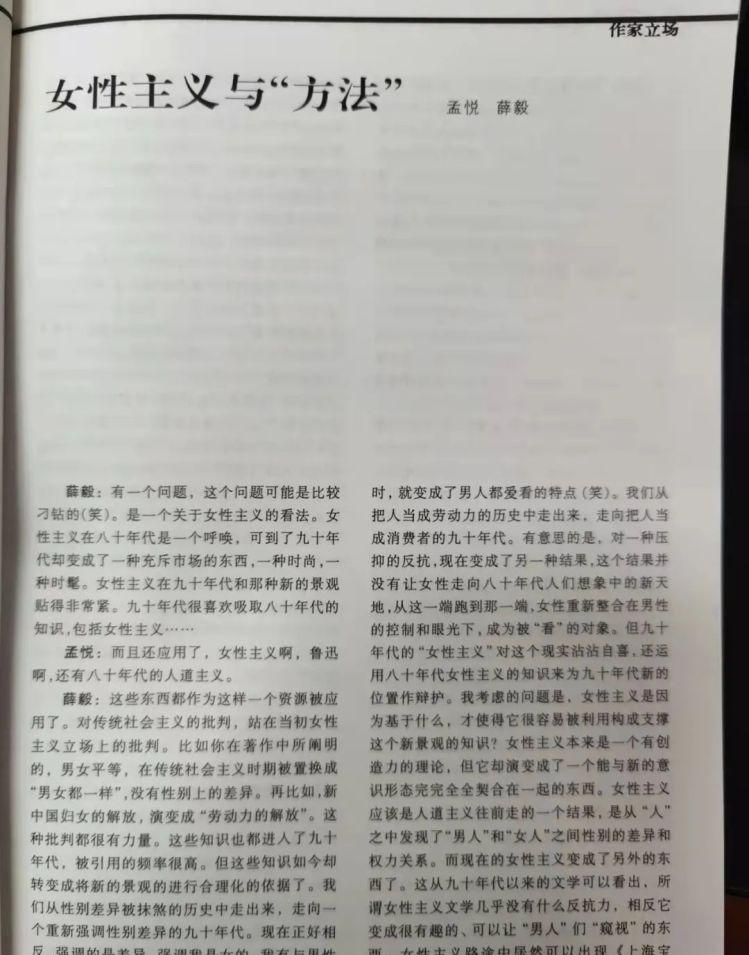

Feminism and the "Method"

Meng Yue Xue Yi

Xue Yi: There is a problem, this question may be quite tricky (laughs). It's a feminist view. Feminism was a call in the eighties, but in the nineties it became something that flooded the market, a fashion, a fashion. Feminism stuck very closely to that new landscape in the nineties. The nineties loved to absorb the knowledge of the eighties, including feminism...

Meng Yue: And it has been applied, feminism, Lu Xun, and the humanitarianism of the eighties.

Xue Yi: These things are applied as such a resource. The critique of traditional socialism stands on the original feminist standpoint. For example, as you explained in your writings, equality between men and women was replaced by "men and women are the same" in the traditional socialist period, and there is no gender difference. For example, the liberation of women in New China evolved into the "liberation of labor force." This criticism is very powerful. This knowledge also entered the nineties and was cited very frequently. But this knowledge has now been transformed into a rationalization of the new landscape. We have come out of a history of gender differences that have been erased and moved towards a nineties that re-emphasized gender differences. Now the opposite is the emphasis on differences, emphasizing that I am a woman, that I have different characteristics from men, but eventually when attached to such a landscape, it becomes a feature that men love to see (laughs). We have come out of the history of treating people as labor force to the nineties, when people were treated as consumers. Interestingly, the revolt against one kind of repression has now become another result, and this result has not led women to the new world imagined in the eighties, from one end to the other, and women are reintegrated under the control and eyes of men and become the object of "watching". But the "feminism" of the nineties was complacent about this reality and used the knowledge of feminism in the eighties to justify the new position of the nineties. The question I considered was, what is the basis of feminism that makes it easy to use the knowledge that underpins this new landscape? Feminism was supposed to be a creative theory, but it evolved into something that fit perfectly into a new ideology. Feminism should be a result of the humanitarian forward, and it is from the "people" that the gender differences and power relations between "men" and "women" are discovered. Now feminism has become something else. As can be seen from the literature since the nineties, the so-called feminist literature has little resistance, but instead it becomes something very interesting and allows "men" to "peek". On the way to feminism, "Shanghai Baby" can actually appear.

Meng Yue: I think several of these problems cannot be said to be related to feminism. Some things are difficult to call feminism, such as "Shanghai Baby", how can it be called feminism? This can be analogous to commercialization, when we talk about cultural identity, cultural identity can become a selling point, and "ethnic minorities" can be such a selling point, of course, feminism can also be so. This is related to the commercialization of cultural mechanisms, and anything that is different and visible may be commercialized because it has a popular effect. And for true feminism, to find out what is marginalized, repressed, deprived of power, what is being deprived? Whether or not female subjects rebel and in what way they rebel is not easy to see in an era of abnormal commercialization of gender. Seriously, I haven't thought about this clearly, and I've even been running away from this question.

Xue Yi: Then I would like to investigate this question more (laughs). You could argue that "Shanghai Baby" has nothing to do with feminism and is the result of commercialization. However, one can also use feminist knowledge from the 1980s to defend "Shanghai Baby".

Meng Yue: This is also an opportunity to think clearly about this issue. I think there are several problems here. First, and perhaps for some, Shanghai Baby is a feminist because it's a definition of women, or a appropriation of women. The feminist critique that Dai Jinhua and I made in the 1980s may be seen as an attempt to fight for women's right to define themselves, from a cultural perspective, focusing on how the overly politicized writing of women's liberation over the past few decades has stripped women of their own voices. One of the biggest differences from the self-written "Shanghai Baby" is first of all the difference in historical times: the society of the 1980s was still a socialist society in change, while the Chinese city at the end of the century was already a new stage for globalization and postmodern commerce. Feminism in the 1980s recognized the premise that in China, the issue of women's economic emancipation and political rights had been solved, and had been solved before Western societies. Whether there is this premise is very important, otherwise we will still be in Lu Xun's era of "what happens after Nala is gone". It enables women to continue to solve the problems of psychological and cultural inequality and undemocraticity that have not been raised by socialist society after they have initially attained equal status in economic and political society. The actual situation of socialist women in the 1980s ensured that the demand for female particularity would not degenerate into a kind of historical regression, that is, a retrogression to the era of "Nala leaving" where women were "used as playthings" and commodities. The problem, however, is that not all definitions of women have anti-gender oppression and the meaning of helping women achieve physical and mental liberation and equal status. In this postmodern post-socialist era, nothing can guarantee that women, their self-definition and self-expression, are not incorporated into commodity logic. In just a few years, hasn't the economic equality of women that generations of people have fought for been sold? This makes the definition and task of feminism suddenly face a postmodern, specious situation. This brings us to the second issue I would like to address, the definition of feminism. Here I look at feminism as a critical discourse. The complexity here is that, on the one hand, any definition and description of women, if it is a violation of another woman, cannot be said to be feminist. On the other hand, women are not a unified unit of analysis, and women are not a social group because they are connected with non-gender concepts such as peasants, urban people, and lower classes. Therefore, I think that the question of what feminism is is very big, and it is difficult to define in the social and cultural and political senses, and it needs to be defined according to each specific situation. Because things are changing all the time. For example, the peasant group suddenly became the edge of the city,—— and such a change of course also happened to women, but at the same time, not all women have the experience of peasant women. When peasant women are spoken of from a feminist point of view, it is sometimes not possible to speak purely from the point of view of gender hierarchy, but to look at its relationship with the power of various societies. And when you look at it when you tie it all together, it gets too complicated (laughs). Therefore, women have become such a relation-dependent concept that it is difficult to treat women as a unit independent of other groups and independent of other social and cultural relations. However, in different social groups, there is indeed a problem of women. This can only be said in particular concreteness.

Xue Yi: Is there such a situation: feminism in the eighties may not have properly dealt with its own equal relationship with other types of groups; women are gender-oppressed, but women's relationship with other oppressed groups is not well explained, as if women's problems are extracted from the problems of other oppressed groups?

Meng Yue: Right. Talking about women as a unified unit can easily create such problems. In addition, the social structure of the eighties was simpler than that of today, and when women were talked about as a unit, the problems that could not be expressed at that time would appear when the social structure was slightly more complicated. It's also a big challenge. I think that for today's feminist researchers, the first thing to do is to set a context to talk about feminism. It's very important in what context you're talking about feminism.

Xue Yi: In this way, you can integrate other things into this context.

Meng Yue: So be sure to use such a method to bring in other related phenomena. When analyzing a work, it is necessary to pull in the text related to it,—— not just the text. For example, when you are talking about a boudoir woman, you must not only bring the men related to the boudoir, but also the relationship between women, that is, the relationship between the boudoir and other women, as well as the relationship between men and men, all at the same time, becoming a panoramic structure, with the panorama to determine the part. Only in this way can we grasp the meaning in which this girl show is oppressed. Because feminism originally wanted to solve a problem of oppression, but if you don't bring this panorama out, it's hard to say who is oppressed in what way. When you talk about women like Boudoir, would anyone say it's an oppressed woman? Because she has a lot of privileges than non-boudoir women. But at the same time, she also has the inequality she suffers. So, it becomes such a debate. But will continue to argue, then her question is important? There's the more important issue of oppression (laughs). Therefore, we must have a good overall positioning before we can talk about this issue, of course, it is difficult to do so.

Feminism later expanded a methodology and field into a research perspective, rather than being limited to the immediate gender equality issues it originally sought to address. Like any field, it can generate a bunch of cultural garbage, and it can also produce meaningful research. For example, DorothyKo's study of women's history in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties shows that women played a very important role in the reproduction of what is generally considered to be a male-dominated scholar-doctor culture. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, a large number of women of the good family were literate and hyphenated, and because they taught their husbands and children at home, the culture of scholars and doctors was continued. Many of the later achievements were related to their mothers. Here, feminist work is to re-evaluate the erased historical and cultural role of women. This valuation not only enriches women's own histories, but also reveals the missing omissions caused by gender ideologies in our historical memory. In addition, there is also a good study of women's special work, labor. Women are usually not counted as productive at home, their labor includes caring for family members, embroidery, and children, where is the surplus value to use? But things like their embroidery slowly spread elsewhere, and even some of the household decorations and handicrafts they created "went abroad", and some of these techniques were later imitated by industrial production. Through such research, this seemingly unproductive labor of women has also been brought into people's historical memory, and the meaning of some concepts of labor creativity has been expanded. In short, to solve the problem of an oppressed group, it is possible to conduct both political and discourse analysis and cultural history analysis, further expanding the repressed cultural memory, and perhaps even to other aspects, including social and economic levels. Expanding and looking at what is really politically oppressed, we may have more and better views of it. The study of women's work just mentioned shows not only the inequality of women's identity, but also the inequality of the division of labor. The inequality of the division of labor involves a broad problem of cultural civilization. What is primary labor and what is secondary labor? This has to do with mental and manual labour, the labour which creates industrial wealth and the labour which creates the wealth of handicrafts, the labour which creates art and the labour that creates science, and the distinction between various labours and the artificial hierarchy. Expand these levels to get a richer panorama. The issue of women's equality should unfold on this panacea. For example, how should women's labor be viewed? Under the hierarchy of labor, you can say that her labor belongs to the lower class, it is not to create scientific results, nor to create technological breakthroughs, let alone profits. But what kind of thing did she create? This needs to be redefined, you have to dig out the value she creates, in order to pull down the things above the level (laughs). We can say that her labor creates a relationship that is far from profit and more direct with life and with people. I think that's the definition of what makes sense for women, what defines feminism. This redefinition goes beyond a simple critique of male power. For if we focus only on how she is oppressed, then the problem of women's labor will be covered up. And when the value of women's labor is dug out, it is more useful to re-examine this problem of oppression and oppression. This definition of women's labor is compared with the set of "Shanghai Baby", and the depth and authenticity are naturally very clear.

Xue Yi: Makes sense!

Meng Yue: Does it make sense? I didn't think much about it either. I sometimes wonder, if you were a woman from the country, where would you feel worth you other than earning money? In addition to earning money for your brother to go to college, are you creative in all this? It's really a matter of division of labor. If we say that the creativity of her labor is relatively small, and the value of scientific and intellectual production is greater, then we are still repeating a hierarchy, thinking that the value of the creation of knowledge or wage earners is greater, while the value of the labor of migrant workers is smaller. Only by finding out the value of the labor of the little nannies of the migrant girls can you eliminate the concept of a labor hierarchy.

Xue Yi: This work is very interesting.

Meng Yue: This work should be done. This includes topics such as what seventeenth-century women did at home, because otherwise she would have no labor, she would have been a well-bred wife. At this point, we can ask what kind of labor her labor is, or what kind of work is the text she writes, and what role does it play in the process of cultural production and reproduction? Recognize these problems in order to find a possibility to pull down the high level of labor (laughs)? The hierarchy of culture is to be broken in a cultural way.

Xue Yi: Right. What impressed me more was that feminism, when dealing with an idea of a side class theory, generally deals with it in this way: class theory suppresses the problem of differences between men and women. Feminism says that in an oppressed group, there are both men and women, and men oppress women. Logically, this should be a deepening, a deepening of feminism in a class conception, but in fact it will in turn become a weapon of criticism of Marxism, because it takes away the relationship between women and men and women from class relations. This brings me to a similar thing. Semiotic analysis that emerged in the eighties has a tendency to go forward alone, and today, semiotics has become a method that people can manipulate alone, text, interpretation, deconstruction, method is very easy to operate. Logically, structuralism and semiotics should go hand in hand, but people forget about structuralism, pull out semiotics, and then take the problem out of context, rather than putting it into an effective structure. Now, this method of withdrawal is very common in literary studies, and feminism has been withdrawn in this way, becoming a test-and-test method, rather than considering problems in some structure. At the same time, literature is also extracted from other problems, becoming an independent pure literary world, an independent symbolic space, an independent text, and then doing a reductive inter-text study, that is, from this text to that text, and the other things that connect the two are not discussed, which becomes a kind of "short-circuit" research.

Meng Yue: "Short circuit", the word is well used.

Xue Yi: In this way, it has created an independent and self-contained imagination about literature, which is independent and self-sufficient, without considering other aspects. This is very much in line with the imagination of feminism as an independent socio-cultural relationship from others.

Meng Yue: Right. Indeed, in a sense, when people treat everything as a method, it is easy to have such problems. In this way, the original starting point is "shifted" by the lateral shift of this method, and finally there is no more. Therefore, being bound by methods is also very scary.

Xue Yi: It's terrible. Under an academic rule, it is easy to become such an abstract method, and then do so, and can be reproduced.

Meng Yue: However, it is necessary to find this primary problem in order to make meaningful research. There is indeed such a problem. This goes back to what I first talked about, and it was precisely because I wanted to see what kind of problems there were that I finally went to the history department. However, the history department has its own methods, which becomes a strange circle for me. So, the question is actually at the level of experience and thinking. Experience alone is not enough, because experience is a process of accumulation, which must go through the level of thinking and, finally, ask questions at the level of thinking. For intellectuals, it is not to repeat the method, but to find problems.

Xue Yi: Is it possible to establish the possibility of being able to identify and point out the abstract application of this method at the theoretical level? Is there such a possibility within the scope of the knowledge you are exposed to? Because of this problem I think it is very big.

Meng Yue: Is there any possibility in this regard? We haven't seen it yet. Because the theory itself is a matter of framework, and you establish this framework, then from this framework you can see what you don't see in other frameworks, or you see a series of concepts and categories. But when you're going to break out of this framework, you're leaving it. I don't know what kind of possibilities you're talking about? Is it to talk about it as a question?

Xue Yi: Right. It is discussed as a problem, not as an abstract method. In this regard, one of my feelings is that Marxism is effective, does it offer this possibility? Because it places a lot of emphasis on analyzing from a historical, concrete level, rather than an abstract level.

Meng Yue: Marx and Engels' Marxism itself has some problems. The Marxist "problem" I am talking about is not in the sense of value but in the sense of doctrine. As a doctrine, it also has some problems. Some people say that it is invalid, and I am not quite sure what this "effect" refers to. I think many contemporary thinkers see Marxism not as a prophecy, but as a critique of capitalism. Whether it works or doesn't work, it still hits some of the fundamental questions of the world. Although Marxism itself does not talk about the Internet and globalization and 9/11, because it still hits the major issues of modern society and history, such as capital, commodities, labor, class, ideology, history, revolution, human alienation and human liberation, etc., its own limitations are also very meaningful and enlightening if anyone dares to dialogue. I think the most interesting theories at the moment are all in dialogue with Marxist theory. The cultural study of Marxism itself has many descendants. From the Frankfurt School, the British Marxists, to Hall, Bourdieu, Jameson, etc. Many of them also talk about abstraction, but of course it is connected with such a big question as the critique of capitalism.

Xue Yi: In his dialogue with various contemporary currents of thought and methods such as semiotics and structuralism, Jameson seems to have adopted such a step, he constantly puts the problem into a larger relationship, rather than extracting it, he can constantly dialogue with various theories. His dialogue is to put the other party in the absolute historical vision of Marxism and reinterpret it, and the reinterpretation is not negative, but in such a structure, in the historical situation, to rediscover the effectiveness and limitations of the other party's method, which is a critical inheritance of Marxism. Otherwise Jameson wouldn't have existed. Is it possible that Jameson's approach provides a theoretical basis for preventing the abstract use of methods, such as feminism, humanitarianism, etc., as just mentioned, and to make the methods become a concrete problem again to talk about and think further?

Meng Yue: Your generalization is quite to the point. Jefferson's ultimate vision of history, and of treating all words expressed in symbols as a deeper causal syndrome analysis, is very useful and can constantly lead us back to the concreteness and problematicity of history. For me, he offers a connection between apparent symbols and real problems that individual theories do not explicitly provide. Indeed, Jameson's theory has this effect on the abstract use of blocking methods. In fact, feminist discourse and humanitarianism can also be used as objects of analytical research. Of course, how to grasp the problem of history and how to explain the relationship between doctrine after the connection is still a more complex and specific judgment. Moreover, the historicized problematic analysis of feminism and the study of feminism are two different kinds of work. The former can make the method a problem again, but it should not replace the latter. As with any study, the study of feminism, as long as it is problematic and not limited to the inertia of the mind, can itself resist the abstract use of what you call the method.

Meng Yue, a scholar, lives in the United States. His major works include History and Narrative, And Strategies for This Article.

Xue Yi, a scholar, lives in Shanghai. His major works include "Words Without Words" and so on.