Abstract: The ornaments or shapes of the combination of man and beast are often found in the bronzes of the late Shang Dynasty and the early Western Zhou Dynasty, this paper attempts to analyze the age and geographical distribution of bronzes related to this ornament or shape, and proposes that this ornament may form and follow the development context of the Huai River Basin to the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and spread north before the second period of the Yin Xu culture. This type of ornament was later transformed and integrated in the Yin Ruins cultural area, and then absorbed by craftsmen in the early Western Zhou Dynasty and further developed in vehicles and weapons.

Keywords: combined ornaments of man and beast; dragon and tiger of The Moon River; bronze ornaments of Yin Ruins; tiger devouring of people; Western Zhou car tool modeling

On the bronzes of the late Shang Dynasty and the early Western Zhou Dynasty, there are many exquisite ornaments or shapes that combine humans and beasts, which have attracted much attention from the academic community. Most of the beasts combined with humans were tigers in the early days, but the artifacts excavated from the tombs of The Yin Ruins and the Western Zhou Dynasty were mostly replaced by dragons; and "combination" means that the images of humans and beasts are inseparable, so this article collectively refers to this mother title as the combination of man and beast ornamentation [1]. In recent years, some scholars believe that such ornaments or shapes are closely related to the bronze culture in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, and have been recognized by a considerable number of scholars[2], but there is still a lack of in-depth discussion and analysis of details such as their modeling and artistic expression methods. Secondly, further discussion is needed on how such ornamentation confirms the importance of bronze culture in the Yangtze River Basin. In addition, the bronze age and geographical span related to this ornament or shape are wide, which should provide important clues for the exchanges between various bronze cultures in the late Shang and early Zhou dynasties.

Based on the above three points, the following first examines the age and geographical distribution of artifacts related to the combination of human and animal type ornaments, discusses the similarities and differences between their modeling characteristics and design techniques, and discusses the direction and significance of their dissemination accordingly. Since the earlier bronzes related to this ornament were excavated in the Huai River and Yangtze River basin areas, and the archaeological and cultural sequences in the area are relatively loose, for the convenience of writing, the following will use the archaeological chronology framework of the Anyang Yin Ruins area as the base point for the generation, and the dating of the related artifacts will refer to the dates suggested by scholars [3].

First, the age and morphological characteristics of the Dragon and Tiger Zun unearthed in the Yue'er River in Funan Province

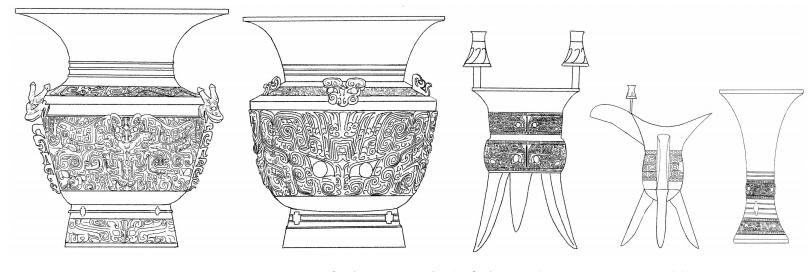

In 1959, villagers in Yue'erhe, Funan County, Anhui Province, recovered eight bronze artifacts from the riverbed, including the Dragon and Tiger Zun (Fig. 1), which were decorated with different ornaments from the same artifacts. This large-mouth folded shoulder is 50.5 cm high and weighs 26.2 kg, which is larger than similar types of utensils. The large-mouth folded shoulder zun appeared in the late Erligang upper culture and became popular until the second phase of the Yin Xu culture.[5] From the late upper culture of Erligang to the large-mouth folded shoulder figure of the second phase of the Yinxu culture, according to the evolution of its neck and mouth edge system, it can be roughly divided into five forms (Figure 2, 1).

Compared with the zuns of the second phase of the upper culture of The Erligang and the first and second phases of the YinXu culture, although the curvature of the mouth of the Dragon and Tiger Zun has increased, the neck is carefully examined from the root upwards, first slightly introverted, and then the large curvature near the middle of the neck is stretched out (Figure 2, 2). Therefore, its shape should be close to the above-mentioned folded shoulder large mouth zun III. to IV. Belonging to the III. style of Xiaotun M333: R2059 Zun's mouth width is not as good as that of Zhengzhou Xiangyang Hui Food Factory Niu Shouzun, but its neck and mouth edge of the outer tension system is basically the same, in this regard, it can also be roughly classified into the III. type, Xiangyang Food Factory Niu Shouzun age in the Erligang upper phase II. section II, and Xiaotun M333 has entered the first phase of Yin Xu culture, so the age of the III. style folded shoulder zun lasts for a period of time, the lower limit may be as late as the Yin Ruins Phase I. The chronology of Long Hu Zun ranges from the second stage of the upper stage of Erligang to the first phase of the Yin Xu culture, and may also be as late as the first phase of the Yin Hui culture [6].

The Yue'er River bronze ware group counts Ascetic 2, Jue 2, Yao 2 and the above 2 figures, the paired Jue, Xue, and Yao are of the same system, and there are five later recovered bristles, which should also be excavated at the same site[7], and the combined form of this bronze is very close to the combination of burial bronzes seen in Yin Xu Xiaotun M331 (Ding 2, Xue 2, Jue 2, Yao 2, and Zun 2). This shows that the Yue'erhe Bronze Ware Group is likely to come from the same tomb, and its owner is closely related to the Shang culture. The casters were apparently familiar with the craftsmanship and shapes derived from the Yin Xu shang culture, but the ornamentation of the Dragon and Tiger Zun was more likely to be related to the local area of the middle reaches of the Huai River.

Compared with the bronze statues excavated in the Yin Ruins area, the two bronze statues unearthed in the Yue'er River account for a large proportion of the abdomen, and the abdominal wall is straight and long. According to Buckley's observation, Yin Ruins craftsmen paid more attention to the bronze shaped lines, so they often added gluttonous stripes to the shoulders, abdominal diameters, and hoop feet; placed three-dimensional animal heads on the shoulder lines; and designed edges along the sides of the vessels, etc., and the main purpose of these techniques was to highlight the lines and visually enhance the ornamentality of the bronze ceremonial vessels[10]. However, the craftsmen who cast the Yue'er River Dragon and Tiger Zun modified the shape of the zun and increased the area of the zun abdomen while considering whether the main ornament was complete and eye-catching. At this point, it is clear that the craftsmen of the two places handled the merchant bronze ceremonial vessels.

The ornamentation on the Yue'er River Dragon and Tiger Statue is commonly known as "Tiger Devouring Man", the high-relief tiger head is placed in the center and above the human head, and the two tiger bodies are opened to the left and right sides instead of the side, and the tiger head and the tiger body form an unnatural 90-degree angle. Depictions of unnatural movements are a common form of artistic expression that effectively prolongs attention and imagination, thereby enhancing the appeal of patterns. The tiger's back is slightly bent down near the center, in the shape of a swooping swoop; the person is squatting, the forearm is bent inward, and the fist is curled, and it is raised to the height of the shoulder. The depiction of the human and tiger figures is profound and interactive, different from the ornamentation of typical merchant vessels. The casting of this figure uses the rare concave and convex corresponding pottery inner and outer fans, Su Honor once pointed out that this method can stabilize the distribution of copper and reduce the possibility of bronze surface fracture, but the operation is also more difficult, more common in the Bronze excavated in the Jianghuai region, it is likely to be a technology developed in the region [12]. The "tiger devouring man" ornament should have other effects in addition to ornamentality for casters. When the craftsman designed this drawing, it is likely that he had touched the same type of pattern on bronze or other carriers and arranged what he saw and knew on this figure; another possibility is that the craftsman witnessed or even closely participated in the ritual activities related to this pattern and was more familiar with the content of this ritual.

The bronze drum from the Izumiya Hirokokan collection in Japan (Fig. 3, 1), 81.5 cm high, is crippled, and the remaining half of the drum has fortunately retained a full-body portrait in a posture almost the same as that seen on the Dragon and Tiger Statue, which is worth noting. The copper drum excavated in 1977 in Baini Town, Chongyang, Hubei Province, is 75.5 cm high and weighs 47.5 kg, which is well preserved.[14] The characteristics of the two drums are similar, and the academic community may think that the place of origin may be similar. The bronze drum of Izumiya has a cloud thunder pattern as a shading, which is close to the so-called "three-layer flower", which is a craft technique developed since the second phase of the YinXu culture, while the Chongyang drum has no shading pattern, so the casting age of the Izumiya drum may be slightly later [15].

The craftsmen of Izumiya Drum shape the human face in a bas-relief manner, which is very conspicuous, wearing a large C-shaped hair crown, a wide and narrow face shape, large round eyes, protruding cheekbones, open mouth and teeth, slightly fierce. And most importantly, the same human face is also seen on the bronze double-faced mask excavated in Xingan Oceania, Jiangxi Province, which is similar in age to the Izumiya Drum. The latter is 47 cm tall and of unknown use, but its design is exquisite, and the canine teeth are also made into a square hook shape like a crown (Fig. 3, 2). The portrait ornamentation on the above bronzes is very similar, which seems to indicate that there was a closer exchange of bronze cultures between the three places.[17]

Second, the use of man-beast combination ornamentation in bronze vessels of the Yin Ruins period

Several bronzes related to the "Tiger Devouring Man" motif have been excavated from the tombs of the late Shang Dynasty in Yin Ruins, and the age is relatively clear. E (Simu E) Da Fangding [18] (Fig. 4, 1) and Xiaotun Women's Good Tomb M5:799 bronze 钺 (Fig. 4, 2) [19] belong to the second phase of the Yin Xu culture, the positive human head in the middle of the pattern has no hair and no crown, and the human face features are highly true, different from the Jianghuai River Basin; the tigers on the left and right sides are presented in a sideways manner, making a semi-squat, the tiger's mouth is open, toothless, and it is swallowing human heads. This kind of "tiger devouring man" ornament appeared at the peak of the development of Yin Ruins culture, although it is related to the highest level of royalty, but its application is limited to more inconspicuous parts or utensils, indicating that although such ornaments are rare, their importance should not be high.

The Yin Ruins craftsmen seem to be imitating the "Tiger Devouring Man" ornament similar to the "Tiger Devouring Man" on the Dragon and Tiger Statue of the Yue'er River, but many changes were made:the human body was omitted, leaving only the head, appearing small, losing the momentum of standing in the middle of the two tigers and fighting against it. The design of the tiger is also unusual, unlike the humanoid kneeling postures such as the R001757 stone tiger and stone beast excavated from the M1001 funerary pit in Northwest Gang, and the small jade tiger and the small jade bear excavated from the Tomb of Lady Hao (Fig. 5), which is similar to the characters representing humanoid figures in the Yin Ruins Oracle bone and the Shang Jin text. The tiger's rear legs and tail in the "Tiger Devouring Man" ornament are used as three support points, and its design should be to imitate the carving shape of stone birds and jade birds, and the bronze owl excavated from the tomb of the woman is also this design. Most notably, the tiger's mouth part is more commonly used to depict the thick lips of fish or dragons. In the understanding of the Yin Xu Shang culture, this tiger-shaped beast has complex characteristics, has the ability of various animals, and can also swallow people. But what is certain is that in their impression, this beast is not a real tiger that belongs to nature as seen by the Yue'er River Dragon Tiger Zun.

The Friar Art Museum has a bronze four-cone footpiece covered with various convex "three-layered flower" bird and beast ornaments, which belong to the late fourth period of the Yin Ruins culture, providing information on the last use of the "beast-eating" style ornaments in the Yin Ruins area (Fig. 6, 1) [21]. The tiger is not seen here, and the dragon head behind the devouring body looks like a female villain on the left hind foot. Her hands clasped around her abdomen, her body seemed to be wrapped in a snake's body, and her shape was very secretive, which contrasted strongly with the ornamentation of birds and beasts (Fig. 6, 2). In Yin Ruins, this design is currently only seen in this second period, and before the late stage of the fourth phase of the Yin Ruins culture, although such ornaments continued to be used by Yin Ruins bronze craftsmen, they were only used in rarer vessels.

The bronze culture in Hunan developed late, and the excavated bronze age mostly belonged to the late Yin Ruins culture, but the high relief ornamentation and semi-three-dimensional shape were its obvious features. [24] The "Tiger Devouring Man" of the Izumiya Bokokan (Fig. 7, 1) and the French Senuchi Museum (Fig. 7, 2) [22][23] were originally intended to be a pair, and were transmitted from Anhua, Hunan Province, belonging to the Ningxiang bronze group that unearthed a number of animal-shaped bronzes. The body of the man and the tiger are surrounded, and the tiger is squatting[25], hugging the villain, the tiger's head is slightly tilted, and the eyes are far away, without a sense of ferocity. On the contrary, although the human body is relatively small, it is fearless, the eyes are firm, the hair is neatly combed behind the ears, wearing a large collared top, barefoot, wearing trousers, and the neckline is carved with a row of diamond-shaped checkered patterns, which is obviously not the clothing and decoration of the Yin Ruins area. This person seems to have a certain status, which should be a portrayal of the local and sacrifice-related figures in the Ningxiang area. The feeling of attachment between people and tigers is closer to the "tiger devouring people" ornament on the Dragon and Tiger Zun of Funan, and its creative ideas may be inherited from the earlier bronze cultures in Anhui and Hubei. However, the craftsmen of the Ningxiang Bronze Group have used a strong three-dimensional sense of modeling, which is likely to be a major breakthrough in the bronze culture of Ningxiang and its neighbors.

Another piece of dragon and tiger statue (Fig. 8) was unearthed in the No. 1 pit of Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan, with a height of 43.3 centimeters and a large body, but its artistic technique was slightly inferior. According to the above-mentioned Zunkou along the arc, sanxingdui dragon and tiger zun adopts the mouth edge of the above-mentioned Yin Ruins Culture III. and IV. style zun instruments, but the Zun body is connected to the middle reaches of the Yangtze River to imitate the high circle foot that is popular in the second phase of the Yin Ruins culture, indicating that its age is later than that, and it should belong to the second phase of the Yin Ruins culture. The bronze pendants and zuns unearthed from the Sanxingdui sacrifice pit display similar artifact shapes, and scholars believe that they should come from the Ningxiang bronze group in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River or the bronze workshops closely related to them. Therefore, the excavation of the Sanxingdui Dragon and Tiger Zun not only proves the inheritance relationship between the bronze workshops in the Huai River Basin and the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, but also indicates that this ornament was handed down in the southern region for at least a hundred years, and the source is likely to come from the middle reaches of the Huai River where the Yue'er River Dragon and Tiger Zun is located, and its lower limit of use is similar to the age of the "Tiger Devouring Man".

Most scholars believe that the people on this ornament represent wizards and reflect the scene of religious sacrifices with beasts. The Dragon and Tiger Zun associated with this ornament, the bronze human face drum in the Izumiya Bogu Collection, and a pair of bronze statues in the Ningxiang Bronze Ware Group represent the peak of development in different regions, and also reflect that the religious ideas related to this ornament were once circulated in the relevant areas, and its development is parallel to the northern Shang culture. The Yangtze River Basin area has not yet found a huge civilization system such as the Shang culture, but from the characteristics of excavated bronzes, it can be seen that from the Huai River Basin to the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, as well as the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and parts of the upper reaches of the Han River, various bronze cultures have established links including exchanging bronzes and borrowing ornamental designs from each other, and at the latest, the second phase of the YinXu culture or a little earlier has formed a cultural circle that is not close but has a large geographical scale. In the process of the development of the world's major civilizations, this situation is relatively rare.

Third, the combined image of man and beast appearing in the bronzes of the Western Zhou Dynasty and its geographical distribution

In the Western Zhou Dynasty, the shape of the combination of man and beast ornaments showed more obvious changes, the shape was relatively uniform, and it was almost only used on bronze vehicles and weapons, and it was found in the early tombs of the Western Zhou Dynasty excavated in different regions.[29] The British Museum's collection of bronze carriages and horses is about 20 centimeters high (Fig. 9), and the lower part is mutilated and indistinct, but the upper part still retains a kneeling little man with a fluttering tiger on the top of his head, and his front palate is tightly wrapped around the human head. Other examples are commonly found on bronze drapes, also in the form of people wearing animal-faced hats (Fig. 10). The animal face mostly follows the design of Shang-style bronzes, but the human face has no fixed features, which shows that when the bronze craftsmen of the Western Zhou Dynasty used such ornaments, it is likely that they only imitated a certain class or group related to the operation of carriages and participation in wars at that time.

Bronze tufts excavated from no. 1 chema pit in Baojijiazhuang, Shaanxi Province (Fig. 11)[32] retain much information about such "crowds". The man had a shaved forehead, his hair was over the shoulders, combed back into a pointed cone; he wore a long-sleeved tunic and trousers with a wide belt, two symmetrical looking deer patterns on the back of the tunic, a neat row of diamond checks at the waist, two small carved rings on the sleeves and trousers as decorations, and his pointed boots seemed to imply that he came from the steppe region.

The early Bronze Swords of the Western Zhou Dynasty in the collection of the Friar Museum also find ornaments that combine humans and beasts (Fig. 12, 1). The knife is 45 cm long, and the dragon's mouth above the back of the knife is open and tightly wrapped around the human head. The obvious difference from the previous example is that the human head is presented in a sideways manner, the hairstyle is also seen for the first time, the left and right sides are shaved, the middle bundle is combed backwards, and a small ball is formed in the back of the head, wearing a feather crown, the legs are bent, and crouching on the other dragon head. According to the records of the Friar Art Museum, the knife was excavated in Xin Village, Xun County ,Henan Province (present-day Hebi City). In 2014, the Tomb of M2 of the Western Zhou Dynasty in Qibin District, Hebi City, unearthed a semi-circular bronze cymbal similar to the "Beast Devouring Man" ornament (Fig. 12, 2), and the human hair was raised upwards, as if in a gallop.

In the early Western Zhou Dynasty, there were several important changes in the use of such ornaments, which can be summarized as follows: the combination of human and animal ornaments has not yet appeared in the bronze containers of the Western Zhou Dynasty, but has been widely used in chariots, horses, and weapons, and has spread widely; the image of people on such ornaments is likely to reflect the ethnic groups that have recently migrated into the previous Shang cultural area; on the M1:21 carriage excavated from the cemetery of the Sanmenxia State in Henan (Figure 13), the human head is hidden in the cone-shaped ornament. Its technique is very similar to that seen on the late Shang bronze foot in the collection of the Friar Art Museum, and combined with the bronze casting process of the same era, the Zhou people's use of human and animal combination ornamentation is closer to the practice of the Yin Ruins culture.

The ornamentation on ancient Chinese bronzes is often referred to as the "motif", derived from the English word "motif". According to the Hanyu Da Dictionary, Zhu Ziqing was one of the first scholars to propose a translation of the word and discuss its meaning, and his Chinese Ballads yun: there are many similarities and differences that are their original purpose, called "motif" in literary terms; the small differences are the details of the branches and leaves that can be added at any time.[36] Visible ornamentation can be subdivided into two categories: the first is the "motif", which is an artistic theme that has been practiced and precipitated over the years, and is not prone to abrupt changes, and there are various cultures[37]; the second type is a relatively general pattern, non-mainstream, and is more likely to change with factors such as age, region or cultural exchange [38]. The combination of human and animal ornaments continued to appear in the bronze cultures of various regions during the Shang and Western Zhou Dynasties, but the YinXu culture was obviously not used on a large scale, and the areas south of the Huai River Basin paid relatively high attention to it, and tried to integrate it into the highly developed bronze craft for a long time, indicating the importance of such ornaments. After entering the Western Zhou Dynasty, the types of instruments that used this motif in various places changed, and also added individuals with distinct images, and the Zhou people's understanding of this ornament seems to have a set of their own statements. The combination of human and animal ornaments witnessed cross-regional and cross-cultural exchanges from the late Shang Dynasty to the early Western Zhou Dynasty, and provided important information for the study of the way the Shang and Zhou civilizations absorbed foreign cultures.

Fourth, the aftermath

In the early stages of the development of many ancient civilizations, human-animal interaction was a common motif [39] (Fig. 14). [40] The double orc statue stone box, now in the British Museum, was unearthed in the city of Hafayeh in eastern Baghdad, Iran, dating back about 2600 BC, depicting a woman reaching left and right to control a snake and beast, presumably the image of a witch at that time. [41] The bronze ware group unearthed in the Luristan region of western Iran, dating from 1000 to 600 BC, has preserved a large number of images of males driving animals, commonly known as "animal masters" in academic circles, and believed to be related to shamanic religious ideas introduced into the steppe regions. Li Xueqin quoted the American scholar Douglas Fraser as a North American ethnological survey, pointing out that the shape of a human being swallowed by a bear or tiger beast was a totem commonly used by the Indians, implying to combine with the beast and gain a new and larger natural force in rebirth. To this day, there are still a large number of traditional works of art that use a combination of man, beast, or man and bird in North America[43] and Polynesians in the Pacific.[44] It can be seen that such ornaments are the common reaction of ancient humans in the face of natural capabilities. The previous article supplemented some research materials on this aspect of the early Bronze Age in China, and it should be pointed out that although the subject matter is the same, the imprints of culture and ethnicity are often reflected in the details of the design and use of ornaments, which is an indispensable link in archaeological research.

(Author: Li Wanxin, Center for Chinese Archaeology, Peking University; School of Archaeology, Peking University.) In addition, the annotation is omitted here, for the full version, please check "Jianghan Archaeology", No. 2, 2021)

Editor-in-charge: Duan Shushan

Audit: Diligence

Chen Lixin

——Copyright Notice——