Very few philosophers have had a great impact like Leo Strauss, but at the same time have a layer of mystery, which is constantly misunderstood while being discussed.

Philosophical protests have been waged around Strauss, believing that he was secretly introducing statism from Heidegger and Schmitt under the guise of a traditional teaching of natural law. The more common philosophical accusations are that Strauss was trying to "impart some sort of secret teaching that contained dangerous anti-democratic sentiments, his preference for the rule of the philosophical elite, and his belief that religion and other 'noble lies' should be used wisely to control the populace." An interesting phenomenon is that a whole bunch of articles claim that Strauss was surrounded by a group of like-minded followers who occupied important positions in many U.S. government agencies during the Reagan and Bush administrations. The allegation was pushed to its peak after 9/11.

In the 1990s, Strauss was translated into the Chinese academic community, but also suffered from the misinterpretation of the importers and translators. For a long time, he was considered a figure who thoroughly criticized and repudiated modern civilization and its knowledge system, and became an intellectual tool for ideological competition.

The Chinese edition of Modernity and Its Dissatisfaction has recently been published, and the following excerpts on Strauss are excerpted with permission from the book. The book is divided into two parts, one is the birth of "modernity", and the other is the criticism and reflection of "modernity". Strauss was naturally included in the second part.

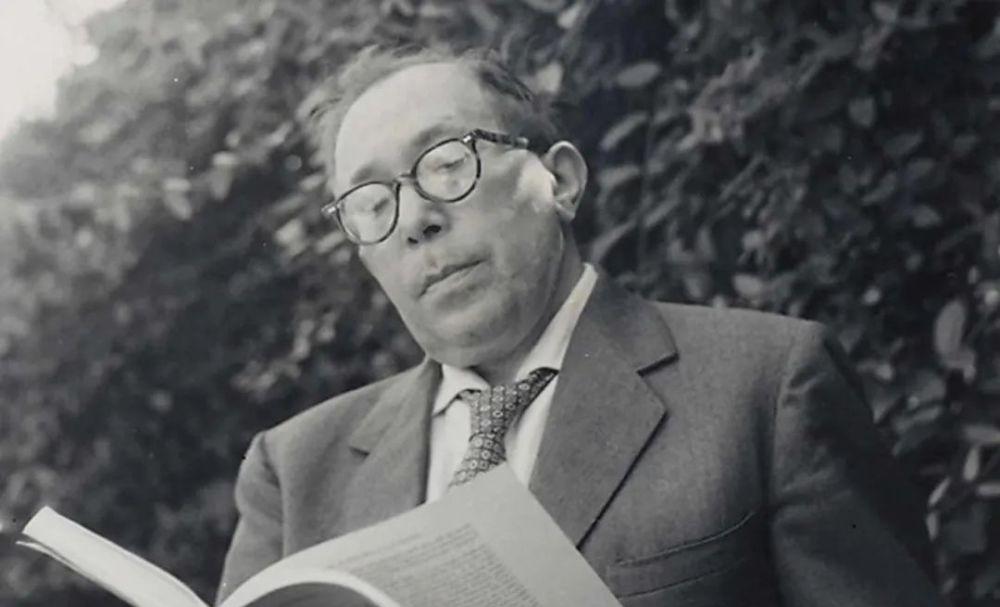

Leo Strauss (20 September 1899 – 18 October 1973) was a 20th-century Jewish German philosopher.

Strauss witnessed and foresaw the problems of modern civilization, arguing that some pre-modern traditional authority was necessary if it were to remain viable and immune from destruction. Much of his criticism and misreading stems from this.

Strauss's understanding of philosophy is not a constructive or constructive activity, but more of a skeptical activity, that is, philosophy is "doubt in the original sense", knowing that it does not know, or knowing the limitations of knowledge. He pursues holistic knowledge, not to get concrete answers, but to pursue the process. Understanding this makes it more likely to understand Strauss's critiques of "positivism" and "historicism," both of which are the basis of knowledge of modernity, and which, in his view, have created a kind of man-made cave, under Plato's natural cave. In natural caves, people see shadows projected onto walls rather than the real world. And man-made caves make it impossible for people to reach even natural caves. According to the understanding and analysis of Modernity and Its Dissatisfaction, Strauss's basic attitude toward positivism and history is reflection rather than denial.

Original author | Steven Smith

Excerpts | Rodong

Modernity and Its Dissatisfaction, by Steven Smith, translated by Zhu Chentuo, Houlang 丨 Kyushu Publishing House, November 2021. (Click on the book cover to purchase)

1

Philosophy, a career

Strauss is best known for his status as a researcher of political philosophy. But his understanding of political philosophy does not omit the usual interpretation of philosophy.

Philosophy, he explains, is the search for "universal knowledge," or knowledge about the "whole." By wholeness, he does not mean some kind of encyclopedic list, a category of all things that exist; he means a knowledge of the "nature of things", that is, the basic category of beings of such a category, for which we can ask "What is...?" "Such a question. We understand a thing by knowing its nature or the category to which it belongs. Philosophy seeks knowledge of categories, not knowledge of special things. With regard to such categories, Strauss gave the example of the knowledge of God, man, and the world.

Philosophy emerged as a unique undertaking because knowledge of this nature was not immediately available. We have more or less reliable opinions about various things, but such opinions often show inherent inconsistencies and may even contradict each other. In Strauss's formulation, philosophy is "a conscious, coherent, and unremitting effort to replace opinions on fundamental political principles with knowledge of the fundamental principles of politics."

Natural Rights and History, by Strauss, translated by Peng Gang, Life, Reading, and Xinzhi Triptych Bookstore, July 2016.

But even if philosophy seeks knowledge of the whole, the whole is fundamentally elusive. We may have knowledge about parts, but the whole remains mysterious, and in the absence of knowledge of the whole, knowledge of parts remains incomplete. Strauss acknowledges that the inconsistency between the lofty ambitions and the negligible results of consistency and integrity "may appear philosophically futile or ugly like Sisyphus," but he goes on to affirm that philosophy "must necessarily be accompanied, sustained, and uplifted by eros." In other words, philosophy is first and foremost an activity of love, consisting more of the pursuit and desire for knowledge than of the completion or realization of wisdom.

Sometimes Strauss associated philosophy with a certain type of causal knowledge. "The dominant passion of the philosopher is the desire for truth, that is, the desire for knowledge of the eternal order, the eternal cause, or the cause of the whole." Strauss again emphasized that desire or passion (i.e., love) constitutes a characteristic of philosophy. This passion is the passion for the knowledge of the cause of the whole, not the passion for the knowledge of anything particular. In fact, this passion for knowledge makes philosophers dismiss human things, which appear "insignificant and ephemeral" in comparison with the eternal order. Since philosophy is primarily concerned with the cause of things—and the form of things (eidos), this makes philosophy seem unconcerned about the particularity of things, including human beings.

Strauss knew—and knew—that there was a clear objection to this philosophical concept. The ancient or Socratic conception of philosophy as "knowledge of the whole" or a knowledge of an "eternal order" seems to presuppose an "outdated cosmology" in which the world behaves like an ordered universe in which humans and other species have their own predetermined roles. Such a concept is completely inconsistent with the modern scientific concept of species evolution and the infinite expansion of the universe.

2

The possibility of holistic knowledge

If everything is constantly changing, then the idea of holistic knowledge becomes incoherent. Is there a whole that can gain knowledge about it? The teleological conception of nature now seems as obsolete as the ideas of creationism and other pseudoscience. Did Strauss reply to this very sharp objection?

Strauss offers a very interesting response to this modern critique of ancient philosophy. He denied that the classical concept of human nature presupposed any particular cosmology or underlying metaphysics. For example, the claim that classical ethics and classical political philosophy are distorted by a teleological physics or a metaphysical biology is completely biased. It imposed on the past the rhetoric of the modern Enlightenment, which held that natural science knowledge was the basis or premise of all forms of knowledge. Strauss argues that the desire for total knowledge remains just as it is—it is only a desire. It does not dogmatically presuppose one or a particular cosmology of one kind or another, let alone claim to indicate a certain cosmology.

Strauss claimed that ancient philosophy understood the human condition in the name of "cosmology-seeking" without giving any specific answer to the question of cosmology. It is the openness or skepticism of ancient philosophy to knowledge as a whole that saves it from accusations of dogmatism and naïveté:"Whatever the importance of modern natural science, it cannot affect our understanding of what humanity is in man." For modern natural science, to understand man with a holistic eye means to understand man from the perspective of a sub-human. But from this point of view, man as a human being is completely incomprehensible.

Stills from the film Socrates (1971).

Classical political philosophy sees people differently. This began with Socrates. Socrates never obeyed a particular cosmology, so his knowledge was about ignorance. Knowledge about ignorance is not ignorance. It is knowledge about the truth and the elusiveness of the whole. ”

Strauss's understanding of philosophy is that it begins with a desire for knowledge of the whole and ends with an awareness of "characteristics of truth that are difficult to grasp." Before the knowledge of the whole is necessarily the knowledge of the part. Since it is impossible for us to acquire knowledge of the whole at once, as if "shot out of the barrel of agun" (this is Hegel's famous metaphor), we must reach the whole in a form of "ascension," a process of movement from what we know at once—the world of "pre-philosophical" experience—to things that are still obscure and shrouded in mystery.

Philosophy must proceed "dialectically" from the premise of universal agreement. This process of ascension proceeds from the opinions we share, which are "in the first place for us", that is, these opinions concern the foundations of the political community, the rights and duties of its members, the relationship between law and freedom, and the laws relating to war and peace.

It is "politics" that provides the clearest starting point for this upward process. Why is that?

3

Political philosophy is the first philosophy

Political philosophy is not just a branch of philosophy as a whole, like ethics, logic, or aesthetics. For Strauss, political philosophy is some sort of first philosophy. The inquiry into political affairs requires us to first explore opinions about the better and the worse, about justice and injustice, which shape and give meaning to political life. All politics is governed by opinions, and political philosophy takes the study of opinions that rule a community— which is usually authoritative opinion written into laws, regulations, and other official documents— as its starting point. At its core, our opinion contains a central assumption about the nature of political life. Without making specific assumptions about law and authority, one does not see the police as a policeman. It is only from the point of view that we can begin this process of ascension to political philosophy.

If all politics is ruled by opinion, then all opinion is concerned with maintaining the status quo or making changes. Change is the desire to make things better; maintaining the status quo is the desire to prevent things from getting worse.

Stills from the movie Metropolis (1927).

Thus it follows that all politics presupposes certain opinions about good and bad and judges change accordingly. "By its very nature," Strauss writes, "political things are objects of support and opposition, choice and resistance, praise and accusation ... If a person does not take them seriously or implicitly or explicitly, then he does not understand what political things are, and he does not understand that political things are political things. ”

But the judgment of good and bad presupposes some kind of idea about goodness, some idea of goodness about community or society. Although not philosophical in themselves, these opinions still share something with philosophy, namely, the goodness of politics, the goodness of the community. But what distinguishes political philosophers from the best citizens or politicians is not a concern for the happiness of this or that political community, but a specific perspective that political philosophers seek to shape the "true standards" of a "good political order."

From one point of view, the political community is a category of existence, which is only one or part of the whole, but from another point of view it is the epitome of the whole. Politics is the most complete way to group human beings within the natural order. Thus, the political order provides the basic structure for all other orders, or determines their order. Of all the perishable things, the heterogeneity of the political order is the closest expression of the heterogeneity of the eternal order. Knowledge of the whole must begin with political philosophy. Whether political philosophy becomes the end point itself or a means of understanding metaphysics, Strauss does not explicitly address this question.

4

Caves and caves under them

In his various works, Strauss emphasized that his method of studying philosophy is best expressed in the works of Plato and Aristotle. This is not only because their works are in chronological order at the top of the list, but also because the ancients were in a superior position over the political opinions that shaped their communities.

These opinions,which Strauss called them constituting "natural consciousness" or "pre-philosophical consciousness"—shaped the moral horizon from which the basic concepts and categories of political philosophy arose and by which they could also be examined. Classical political philosophy, as Strauss presents, is directly related to political life, and all subsequent philosophies are equivalent to a revision of this tradition and therefore can only experience their world indirectly, that is to say, to see the world in secret through a piece of glass. Natural experience is further distorted through philosophical traditions that have intertwined with theology, science, and, more recently, with history, at different times. Thus, we now experience the world through a prism of concepts that prevents us from reaching the vis-à-vis of philosophy as opposed to the city-state– to borrow John Rawls's expression , "primordial position."

Strauss sought to explain the natural condition of philosophy through Plato's famous metaphor for the cave. Strauss believed that Plato's cave was not just a state of darkness and superstition. It represents a natural vision of everyday life, a world in which we all live and act. The "prisoner" in the cave, Plato's idea that there are still some primitive pre-philosophical underpinnings of experience, derives from Husserl's idea of the "living world," but it is still not fully theorized here in Strauss.

That's how they are—bound to each other and can only see the heads projected on the wall, and the fire burns behind them. Socrates said that these people—passive and intoxicated—were "just like us." This metaphor is similar to the modern cinema or television screen, in which the observer passively accepts the images he sees in front of his eyes, but is never allowed to see the causes of those images. The images, in turn, are controlled by "puppet manipulators", who only allow the inhabitants of the caves to see what they are allowed to see. The puppet manipulators were first and foremost legislators of the city-state, the founders, statesmen and legislators of the city-state, the ones who brought laws and codes of justice. Alongside them were poets, mythologists, historians and artists, while below them were craftsmen, architects, urban planners and designers. All these craftsmen contributed their part in decorating the various caves that made up political life.

The novelty of our situation—and the originality of Strauss in the use of cave metaphors—is that we no longer dwell in Plato's cave, but dig ourselves a cave under the natural cave, which creates further obstacles to the pursuit of philosophy. It's as if:

People may become very afraid of ascending to a place where there is sunshine and will be tempted to make it impossible for any of their descendants to achieve this ascent. So they dug a deep pit under the cave where they were born and retreated into it. If a descendant wants to ascend to a place where there is sunlight, he must first reach a height parallel to the natural cave, and in order to do so, he must invent a new, thoroughly artificial tool that the people who live in the natural cave do not know, and this tool is unnecessary to them. If this man stubbornly believes that by inventing new tools, he has surpassed his caveman ancestors, then he is a fool who will never see the sun and will lose the last bit of memory of the sun.

What is the cause of this new pit, the cave under this cave?

Strauss image.

5

The limits of positivism

As for the causes of this new and unprecedented situation, Strauss traces the wrong path that modern philosophy itself has experienced, as well as the wrong path that its "twin sisters" science and history have experienced.

It must be said that he is not opposed to science and history itself. He was opposed to the transformation of science and history into two pseudo-philosophies that unfolded in the name of positivism and historicism, which constituted the greatest obstacle to the restoration of philosophy.

Positivism is the belief that "the kind of human knowledge that modern science possesses or aspires to is the highest form of knowledge." Positivism necessarily devalues the value of all non-scientific forms of knowledge, whether it is traditional beliefs, folk wisdom, or simple common sense. Only things that can withstand the test of scientific scrutiny and control can be regarded as knowledge.

In the social sciences, positivists usually insist on the fundamental distinction between facts and values, arguing that true knowledge is concerned only with facts and the relationships between facts. Values and "value judgments" are purportedly matters of personal choice and are therefore outside the scope of knowledge. Thus, attempts to rank or evaluate different political systems and different claims to justice were considered impossible from the outset.

Early short film "Grandmother's Magnifying Glass" (1900).

The problem with positivism is not only that it distrusts all pre-scientific forms of knowledge and tries to break with it, but also that, through complex scientific means, it merely confirms what "every ten-year-old with a normal IQ" already knows.

The reductionist theory of science ("knowledge from the far-reaching to the microscopic") may be valuable in some fields, but it is not when applied to the social and political world: "Some things can only be seen in the eyes of citizens who are very different from the observers of science. In homage to Swift, he declared that demanding scientific accuracy would not make things clearer but only distorted, but would only lead to "research projects of the kind that shocked [Gulliver] on the floating islands of Laputa."

6

The limits of historicism

The second and more significant cause that leads us to descend beneath natural caves comes from historicism. We should not confuse historicism with history, a discipline that Strauss admired; on the contrary, historicism is concerned with the corruption of history. Historicism is the belief that all knowledge—scientific or philosophical—is historical knowledge, that is, an expression of the time, place, and circumstance in which it is located. Positivism insists that there is a kind of knowledge, scientific knowledge, as the source of truth. Positivism still has at least a modicum of connection to the philosophical tradition, no matter how fragile it may be. Historicism, on the other hand, holds that even the question of truth, the question relating to the "permanent character of human nature," is a relapse of the old disease of a certain "decaying Platonism", which has the idea of eternal truth and the idea that society has a correct order.

According to Strauss, historicism, by its own standards, has also failed. Historicism is the belief that all ideas are products of their time.

But if all ideas are products of their time, this must be true for historicism itself. Historicism, however, paradoxically excludes itself from the judgment of history. All ideas seem to be historical, except for the historicist idea, which is the notion that all thought is historical. Also problematic is that historicism fails to provide a full explanation for the ideas of the past.

The modern method of history requires an understanding of the past as it really happened, the eigentlich, or as it actually understood itself. But if we read works such as Plato's Republic or Rousseau's Social Contract as a product of their time, they cannot be understood in the same way that Plato and Rousseau understand themselves. They are not historicists, so imposing historicism on their work is a distortion of the understanding of true historicity. The imposition of some form of historicism in the history of ideas is itself a modern construction.

How can we extract ourselves from these dogmas that make up the caves beneath Plato's caves?

7

Ascend towards the "natural cave"

Strauss admits that we can no longer know directly the original meaning of experience, the original meaning of the city-state and its gods, which are pre-theoretical conditions of philosophy. It is overshadowed by layers of frozen traditions that have managed to obscure it from our vision.

But ironically, Strauss argues that this isn't exactly a bad thing. Since historicism destroyed all previous philosophies, we live in an era in which the disillusionment of tradition makes it possible to reflect on tradition. If we want to emerge from the second basement and ascend to the natural caves that make up all the philosophical premises, such a reflection would require the creation of "new tools that are completely man-made."

Strauss and his study.

Paradoxically, these new tools were taken out of the same toolbox of historicism, which Strauss seemed to oppose. Although historicism may dogmatically confine philosophy to the circumstances of its time and place, it can also be used against itself. Strauss argues that there is the possibility that, by focusing on the circumstances in which philosophy finds itself, historicism may unconsciously lead to self-destruction: "Historians may believe that the true understanding of human thought is to understand each doctrine according to a particular epoch, or to understand each doctrine as an expression of its particular epoch.

If the historian begins his inquiry from this conviction, he must be intimately familiar with the idea that his initial conviction was unfounded. In fact, it was the subject he explored that kept stressing this to him. Not only that, but he was forced to realize that it was impossible to understand past thoughts if he was guided by that initial belief. This self-destruction of historicism is not entirely an unexpected result. ”

Strauss's answer is that it is only through historical study that we can remind ourselves of the original situation of philosophy. Ironically, in order to become more historic, we must first free ourselves from the confusion of historicism. Only by regaining the skill of careful reading will we be able to begin this slow and painful ascent from the man-made cave in which we now inhabit, towards the "natural cave" on which future philosophies are based.