In the modern era of "intellectual and institutional transformation", a large number of Western imports were transmitted to China either directly or through Japan. The explosion of knowledge is in line with the urgent needs of the Chinese people to transform; the transition between the old and new systems also provides space for new knowledge to play. As a result, the state, society and individual accept and even create new knowledge to varying degrees, leaving a large number of specific topics for future generations to discuss.

Stimulated by the crisis of the times, "lucky" imports were rapidly promoted with official support, such as education, Western medicine, and agronomy. In contrast, some imported products are not so "lucky", such as hypnosis. Hypnosis spread to China, around the same time as the introduction of other new knowledge, but was on the fringes of national attention and even resisted and suppressed. "Hypnosis and Popular Science in Modern China" returns to the historical scene, combing and reflecting the embarrassment faced by this new knowledge in the dissemination. The author, Mr. Zhang Bangyan, keenly finds the angle, and since hypnosis has been ignored by the upper echelons, it provides an opportunity to examine how the "public" plays the main role "from the bottom up". The author cares about "popular science", has a strong sense of problems, carefully lays out historical facts, adds relevant theories, and constructs a historical narrative of how "the public" shapes "science", which not only reproduces the historical ups and downs of modern hypnosis, but also for today's readers, it also has the role of unveiling the mystery of hypnosis in the historical vision, making the reading process full of harvest.

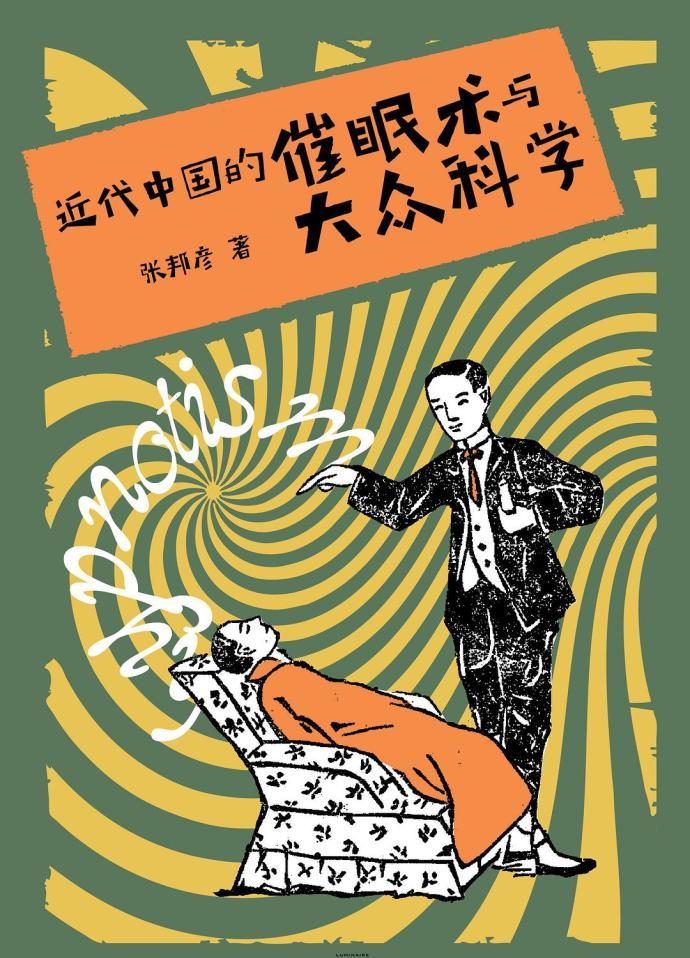

Zhang Bangyan, "Hypnosis and Popular Science in Modern China," Shanghai People's Publishing House, November 2021

The author's impression of reading and learning this book is that the embarrassment of hypnosis is that "learning" is not as good as "technique". This is from the perspective of the parties, in contrast, the author is more interested in the actual words and deeds of the hypnotic advocates of that year. There should be some criteria for judging whether a new knowledge is "learning", such as whether there is a mature knowledge system, an academic community organization, a specialized practitioner, and whether it can purely (at least pursue) the pursuit of accumulation and renewal within the knowledge system. According to this point of view, hypnosis in the late Qing Dynasty and early Ming Dynasty is indeed inherently insufficient, as the author points out in the introductory section, the development of Western hypnosis has undergone more than a century of intellectual evolution, while East Asian hypnosis has been compressed in the second half of the 19th century. Those pioneers who actively engaged in hypnosis were not academics, most of them only had the experience of studying in Japan, and even the experience of studying was no longer available; the ideas they relied on to spread were mostly second-hand knowledge from Japanese referrals; their activities lacked official, university, and other support, and could only organize themselves, until 1937, when individual groups were officially filed.

They made positive efforts to "endow new poems", such as spontaneously establishing societies and writing books to distinguish them from the "jianghu warlocks", and actively standardized the forms and procedures of hypnosis experiments and case reports to strengthen their "scientific" appearance. In particular, in the fourth chapter, the author traces the interaction and co-evolution of hypnosis, spirituality and psychology, rising to the height of interdisciplinary influence, trying to prove that hypnotic advocates try to establish an explanatory framework that integrates hypnosis and spirituality, and their claims and spirituality are both blended and demarcated, which in turn affects "academic science", and in the polarization of "science" and "spirit", they even "vaguely speak of a third voice".

However, from the perspective of actual performance, hypnosis behavior is more inclined to become "art", that is, the application and instrumentality of hypnosis overwhelm academic rationality. On the one hand, the nature of hypnosis itself for treatment is due to the nature of therapy; on the other hand, there are also the active construction and last resort of these advocates, who may not be able to immerse themselves in research, but must consider the practical factors such as attracting audiences, self-packaging, and catering to commercial needs, such as borrowing professional titles such as "doctor", reflecting their need to move closer to professional identity; they will also cooperate with the government to serve hypnosis as a national tool, such as on page 70, Bao Fangzhou was commissioned by the Shanghai military authorities to use hypnosis to obtain confessions. In the eyes of others, hypnosis is often related to political means, criminal means, performance, and supernaturality, which strengthen the "magic" attribute of hypnosis at the audience level. The superiority of "magic" sometimes depends on the character action machine of the person who uses the skill, and it is no wonder that hypnosis was once suppressed and rejected. It is said that "the truth is more and more clear", hypnosis in the ko-occult controversy "continued to be present", but "absent from the debate", as the author points out, hypnosis advocates "often use scientific concepts imprecisely, and many speculations and experiments are untenable", and the subsequent decline of hypnosis is probably inseparable from the hard wounds of their own knowledge system.

The three illustrations on pages 110-111 are interesting and may reflect this problem. The three figures are from the pages of three hypnotic literature, namely "Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis" by Tetsushi Furuya in Japan, "Lecture Notes on Correspondence In Hypnosis" by Bao Fangzhou, and "Lecture Notes on the Latest Experimental Hypnosis" by Tang Xinyu. It can be seen that these three pages are very similar. In this regard, Hypnosis and Popular Science in Modern China points out that domestic hypnosis advocates are "good at systematically translating Japanese resources into self-made lecture notes of the society, and imitating the usual japanese textbook style... Sometimes we may even find that there is a high degree of overlap in the content of the lecture notes of the two societies."

However, the author does not seem to compare the text further, mentioning only the sentence "it is likely to be all references". In fact, Bao Fangzhou and even others are not only "references", but also a large probability of copying. The full text of the second volume of Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis can be found on the Library of Japan Digital Collection website, as well as the table of contents of the sixth volume. Comparing the table of contents and some pages, it can be inferred that Bao Fangzhou collected the multi-volume lecture notes of The Ancient House into a book during his time in Japan, and published it under his own name. Furuya Tetsushi's lecture notes were published in 1912 and Bao Shu in 1915, and the distribution address was in Kobe, Japan, and the time and place logic is also consistent.

Title page of the second volume of Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis (from the National Diet Library)

Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis Volume II (from the National Diet Library)

Bao Fangzhou's "Correspondence Lecture Notes on Hypnosis" cover and copyright page

Bao Fangzhou's original book "Lecture Notes on Hypnosis" has no catalog, and there is a text version of the catalog on the ancient books online, which can be seen in comparison, which basically coincides with the catalog of "Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis" by Furuya Tieshi

Some pages of Bao Fangzhou's "Correspondence Lecture Notes on Hypnosis" on "Principles of Hypnosis" are highly similar to those in Furuya Tieshi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis

It can also be seen in the catalogue of the sixth volume of Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis that the original book is accompanied by a "Collection of Member Experiment Reports", that is, experimental reports of personal participants from various parts of Japan. This practice is probably also an abuse of the "experimental report" mentioned in pages 135-143 of Hypnosis and Popular Science in Modern China. The "References" of the book only lists the second volume of Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis, and there is no sixth volume.

Furuya Tetsushi's Lecture Notes on Higher Hypnosis, Volume VI, Partial Catalogue (from the National Diet Library page)

The above situation reflects the situation of domestic hypnosis advocates in the early days of "giving new poetry". Bao Fangzhou's book is only one of many Chinese works that refer to Japanese literature, and if we can make further textual comparisons of these documents, we may enlighten other questions: Have these domestic hypnotist advocates transformed or innovated when referring second-hand knowledge of Japan, and whether there are any efforts to localize and localize them? Are these highly overlapping cases in the early stages, or are they always present, and are there any significant changes in their knowledge structure in the early and late stages? We can even think about whether these advocates in China have made a contribution to or abandonment by these advocates in China in the process of transmitting Western hypnosis doctrines from Japan to China or directly to China. These details, if fleshed out, should be helpful in enriching and refining the narrative of "lower" efforts. As the author mentions in Chapter IV, pages 158-159, after the 1920s, the Hypnotic Society remained in contact with Japan, but relied less and less on Japanese theories, and some institutions began to actively contact European and American spiritual institutions.

"Hypnosis and Popular Science in Modern China" can piece together the historical materials that "lack systematicness, coherence, and consistency", overcome the shortcomings of the historical materials themselves, and paint a picture of hypnosis in modern China. Some historical materials themselves are doubtful, and the author himself has also mentioned it, such as the "Chinese Spiritual Research Association" claiming to have nearly 100,000 members, which is quite suspicious, and the author has analyzed this on pages 105-106. This may reflect the problem that the material left by hypnotist advocates inevitably has self-proclaimed intentions, and if there is not enough other historical data to circumstantial evidence, the "lower" efforts cobbled together by these "self-statements" will be somewhat discounted between the "real". In addition, the vast majority of these hypnotic advocates are no longer known, and little is known about their lives, which leaves some regrets. Like in modern times, there are many advocates of rural educators, but the knowledge structure and behavior motivation of the participants are quite different, resulting in uneven activity levels. By analogy, different individuals who advocate hypnosis and even deduce "popular science" will inevitably have similar situations. For example, Bao Fangzhou, Yu Pingke and several other key characters are from Zhongshan County, Guangdong Province, whether the regional factors behind this have played a role, in addition to their specific motivations, whether there are conceptual differences between them, these have left room for imagination.

The representation of chronology in the whole book does not seem to be uniform, such as "1880s" on page 28 should be "1880s", and other pages 68, 101, 138, 139, 153, 220, 221, etc.

The references are divided into three parts: historical materials, papers, and monographs. Among them, the number of "historical materials" is at most relatively general, or it can be classified and sorted in more detail according to the nature of the literature. In addition, the articles quoted from republic of China periodicals such as "Soul" and "Spiritual Culture" are specially listed, but the articles quoted from newspapers and periodicals such as "People's Daily", "Guangming Daily", "Declaration", "Ta Kung Pao", "Education World", "Family Friends" and other newspapers and periodicals are not listed, only the names of newspapers and periodicals are listed.