This article was published in the "Beijing News Children's Book". Beijing News Children's Books (xjbkids) is the children's book rudder of Book Review Weekly, which has joined forces with many publishing brands to select children's books for readers and answer educational puzzles.

——

There are a large number of imported books in the children's book market, and at present, we are still talking about picture books based on pictures, and for children's literature works based on words, they mainly rely on the aura of the works to attract attention, such as the awards won by the works overseas, the popularity of the authors and the recommendations of certain institutions. As for why the work itself has won awards, why the author wrote it, whether the work has followed a certain history, what innovations have been made, and most importantly, what these mean to children and adolescents is often unknown to the public. Coupled with the differences between Eastern and Western cultures, it also affects our understanding of works to a certain extent. As a direct result, some children's books are bought home, but they still don't understand why the slogan calls it a classic.

Therefore, starting from this issue, we will launch a new column called "Children's Literature General Studies Course", starting with the children's literature of Britain, France and Germany, which has more classic works, and extracting a variety of themes, including "children's literature during World War II", "people and animals in fairy tales", "adaptation and circulation of fairy tales", "how children's literature is presented in movies", etc., to explore the cultural factors behind the works and the meaning they really want to express.

The two authors of this column are Sang Ni and Zi Ye, who major in comparative literature, and Sang Ni graduated from Barnard College at Columbia University and Zi Ye graduated from Brin Mawr College, and these topics come from the children's literature class they took when they were visiting students at Oxford University. Each article was completed after more than an hour of one-on-one discussion with the professor, and went through a large number of materials to consult, find ideas and outline the process. There are some ideas that may be quite bold, and you are welcome to discuss them with us.

Although children's literature is a discipline, the relevant books are selected by teachers, parents and other adults for children, and it is often difficult to agree on the educational purposes of adults and children's interests, and the definition of children's literature is constantly being discussed. The first issue of today's push is Sang Ni's article, originally titled "Big Question: What is Children's Literature?" "From the relationship between the writer and the work, we can see the conceptual expression of the writer hidden in children's literature. Huang Xiaodan's article "So far, my understanding of the world has never exceeded the books I read in my childhood" can also confirm this expression from the reader's point of view.

It should be emphasized that children's literature in a broad sense includes all books for children such as picture books ( Children's Books ) , but in the audience market of children's books , children's literature generally refers to text-based novels , and this narrow definition is used below.

Written by | Mulberry

01

We need to explore

The relationship between children's literature authors and their works

Many well-known literary critics and scholars, such as Canadian scholar Perry Nodelman (the masterpiece "The Joy of Children's Literature"), Peter Hunt (Professor Emeritus of Children's Literature at Cardiff University, UK) (Masterpiece "Criticism, Theory and Children's Literature"), Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, Director of the International Childhood Studies Centre at the University of Reading, UK Power and Children's Books: Teaching Myths, Fairy Tales, Folk Tales, and Legends), among others, has tried to create a viable discussion scope and framework for "children's literature".

In the process, they either try to theoretically define the "genre" of "children's literature" or look for its relationship to and influence on readers, publishers, and literary traditions. The same pre-emption is that both "Children's Literature" or "Children's Books" prioritize a specific audience—children—even though children's literature is actually a game for adults.

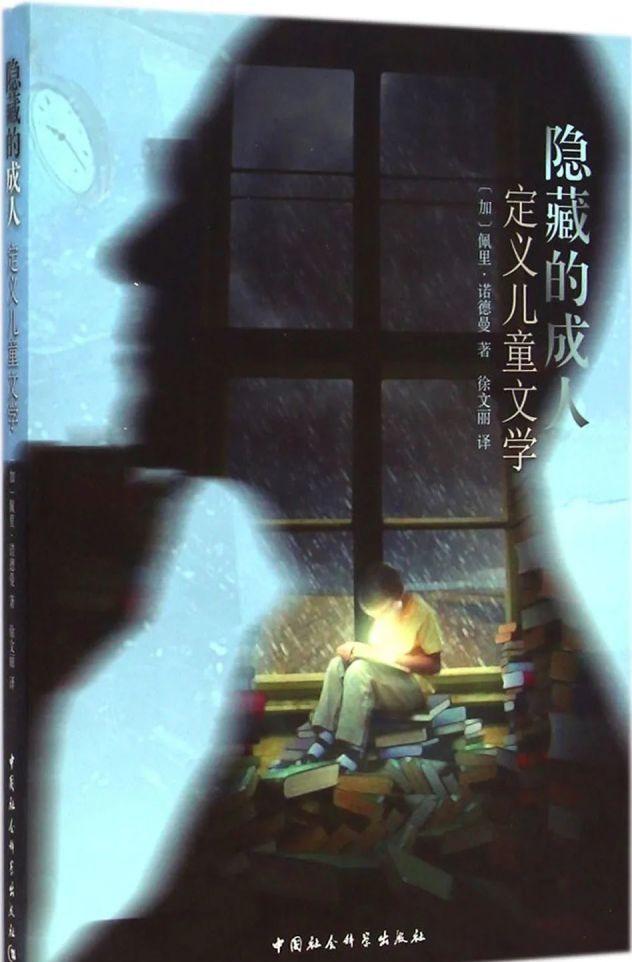

Hidden Adults: Defining Children's Literature, by Perry Nordman[ Canada, translated by Xu Wenli, China Social Sciences Press, November 2014.

As Perry Nordman notes in his book The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature, "Children's literature is what publishers want children to read, not what children want to read." These "children's books" are not only created by adult writers, but also mainly aimed at adult buyers, including parents, librarians and teachers, and the criteria for these adults to buy children's books are based on their understanding of "what kind of books are suitable for children to read". From this point of view, the "category" of children's literature is largely controlled and shaped by adults. In the process of being defined, manipulated, created, and imagined by adults, "children" and "child readers" often become passive objects.

While many scholars have conducted in-depth discussions based on the power relationships between "children" and adults, their theoretical analysis focuses more on how "children's literature" affects readers from the reader's perspective and what message these works convey, and does not explore the relationship between children's literature authors and their works.

It is worth noting that when a "book for children" is created and put on the market, it is readers and critics who decide whether it is suitable for "children" to read. The authors of these books have no say in whether their work should be defined by a particular literary genre label, notably the novel "Marry Poppins" (the film of the same name, which was nominated for best picture at the 37th Academy Awards, about a fairy who incarnated as a nanny to come to the two children to help them feel family and friendship again) has always been regarded as a classic of children's literature, but its author Pamela Poppins has always been regarded as a classic of children's literature. Pamela Travers has bluntly denied that the book is "literature for children."

Stills from the movie "A Man of Joy" (1964).

02

Works classified as "children's literature"

It is likely not written for children

In many discourses, the most important questions about authors and creation itself are not discussed and answered: Who are these authors writing for? What motivates them to create a childhood in their work? What kind of psychological desires are hidden behind the "world of children"? Answers to these questions will help to understand the birth mechanism of "children's literature" and thus help us to gain a deeper understanding of the commonality implied by "children's literature" as a literary category. In the following discussion, I will explore why we should pay attention to the creation of children's literature from the perspective of authors, and their relationship with the "created childhood" in the book.

In my exploration, I found that many writers do not want their work to be included in the category of "children's literature". Writer Scott O'Dell (blue Dolphin Island) has mentioned that "the works classified as 'books for children' are not actually written for children", and J.K. Rowling has said, "If a book is attractive, it should be attractive to everyone".

Blue Dolphin Island, by Scott O'Dell, translated by Fu Dingbang, Sunray Press, May 2017.

On the one hand, their view is that their works should be valued as much as "serious literature" and should be universal, rather than being bound and restricted by genre. At the same time, they are also pointing to the "invisible elephant in the room" in the discussion of children's literature – some of the elements used in children's literature, such as innocence, fantasy worlds, and relatively intuitive story lines, make them inherently more shallow than adult literature. In this way, the prejudice against children's literature is created on an arbitrary categorical dividing line, ignoring the concept of "creating for children" in which "children" refer not only to children who are young in biological age, but also to children who have "grown up".

Of course, it should not be overlooked that many works that are regarded as "children's literature" do use relatively more intuitive literary techniques and techniques. So what makes these writers so confident that their work contains "enough depth and complexity" to rival the work of Dickens or Shakespeare?

The famous fantasy writer Phillip Pullman (the masterpiece "Dark Matter Trilogy") explained the controversy in a 1996 speech: "There are some themes, the core of which is too grand for adult works; they can only be well presented in children's books." Based on Pullman's remarks, Peter Hunt made a more in-depth and detailed interpretation: "The adult brain ... The brain is less likely than a child's brain to accept images, atmosphere, and unguided recessive ejaculations."

He may imply that when readers have a "childlike vision", they are more likely to jump out of the ideological, definition, thinking inertia, and other elements of adult social life, and it is easy to understand more possibilities and profound meanings from the text (at this time I think of the Taoist doctrine of namelessness). This may explain why the protagonists in many children's literature must be children, because the childlike pure vision is the core of these works.

Stills from the first season (2019) of the British drama Dark Matter Trilogy.

03

Taking a step back from the adult world,

Then use the child's perspective to examine and challenge adults

Freedom to break free from ideological constraints has many benefits. When the author abandons many of the rules and dogmas of society, he is also seeking a freer creative space for himself. This free creative space allows their characters to explore themselves more deeply, and even ask irrational "childish questions" to show the character's inner thinking, and these reflections also show the protagonist's awareness of the self, the individual, and the relationship with the outside world.

In the case of Alice in Wonderland, its main characters often ask seemingly inconceivablely ridiculous questions while searching for answers that seem nonsense, and it is this journey of thought and exploration that makes Alice truly "herself."

For example, in Alice in Wonderland, the second book, Adventures in the Mirror, Tweedledee asks the Red King what she saw in her dream, and he says, "If he doesn't dream of you anymore, where do you think you will be?" You're nowhere. Why, because you're just a thing in his dreams. "The series of questions and answers of the bullet is one of the core thinking of existential philosophy. Alice's story constantly challenges the characters' established perceptions of the outside world and the self, such as the Red Queen's constant encouragement of Alice to believe in the impossible, and also shows the author Carol's understanding of the "individual" - the protagonist is becoming a person who embraces change, intuition and casualness, and constantly thinks about the relationship between the self and the outside world (sometimes even metaphysically).

At the same time, such creations create a relatively safe space for writers to take a step back from the adult world and examine, challenge, and critique it from the perspective of a child.

J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series created a real-world replica of the wizarding world, in which there are conflicts between race, class, and other elements. The story takes place in the teenage Harry Potter and his friends, who constantly expose and rebel against the "dark" side of human nature in their adventures and against Voldemort. Of course, their trio is constantly breaking all kinds of rules and showing precious courage, righteousness and kindness, which contrast and echo the behavior of adult characters.

Literary critic Karin E. Westman has written: "By fusing a narrative approach that values empathy with Harry and the category of bildungsroman, Rowling encourages her readers to look at the adult world with both skepticism and empathy, and Rowling pays more attention to how fantasy literature provides a perspective on everyday life experiences and the individual's place in society." It can be seen that choosing to use children's perspectives to tell stories with social critical significance can also reflect profound ideas and themes.

Stills from the movie Alice in Wonderland (2010).

04

the process of recreating childhood,

It is also an opportunity to explore a relationship with the self

On the basis of creating story lines and characters, the process of recreating childhood may provide writers with an opportunity to actively or subconsciously explore their relationship with themselves and to think existentially. As the critic Karin Lesnick-Oberstein writes: "A theory of psychoanalysis supports my conception that 'child' is constructed and created, and also offers a different way of exploiting the idea of the constructed 'individual' ('child' and 'adult')." This issue and direction of self-exploration can be confirmed by the views of many authors, who invariably emphasize that they are writing for themselves. Children's literature writer Wliam Mayes wrote directly, "I write for myself, but a me a long time ago," and J.K. Rowling once said, "I write mostly for myself."

But what exactly are they saying, "I'm writing for myself?"? What is the relationship between their "self" and their work? I have found that the authors express several different levels of motivation and awareness:

(1) They are eager to return to childhood and become children again. The writer Ivan Southall once wrote: "I am with the child with all my heart, I become a child, in the paper of a book my heart beats with the heart of a child, I become a child ... This child should be a part of you." This writer expresses a desire and nostalgia to return to childhood and become a child, and also expresses the importance of people's "childhood" period for self-knowledge.

Many people and writers regard carefree childhood as their "golden age" and apply many elements observed as children to their own works (including George Orwell, who also expressed his nostalgia and love for childhood frankly, and Shen Congwen's works often have childhood-related elements).

(2) As Freud proposed, a person's childhood is the key point in establishing the "self", and these authors also enter and explore the subconscious that shapes self-perception at a deeper level through writing. The theorist Francis Spufford, who once made a very strong point about the benefits of adult reading children's literature, said: "These books become part of our self-cognitive process." The stories that mean the most to us are incorporated into the process by which we truly become ourselves. ”

Many writers have bluntly expressed the joy of being a child again when writing children's books, such as Roald Dahl once said: "I laughed with the children because of the same jokes... And that's why it's always the best inspiration. And Lewis Carroll also said, "When we write for children, we are using the same elements of our imagination as our children." Peter Hunt also referred to the nonsense elements in Alice in Wonderland as "interesting nonsense." Although the writers mentioned above come from different historical periods, their views invariably mention the importance and pleasure of thinking from the perspective of children, and the key entry points brought to their creations.

Illustration in Roald Dahl's The Witch.

05

When depicting the imaginary world,

The yearning for childhood joy is also incorporated into writing

On this basis, I will make a third point about the driving force behind the writing of these writers: these writers, while reconstructing their childhood and depicting the imaginary world, also integrate their own yearning for the pure joys of childhood into their writing.

Their writing may be a way of rebelling against the ideological, political, social, and other oppression of all living individuals in the adult world. In the worlds they create, they can manipulate all the "elements of reality", use their imagination to reorganize these elements, and enjoy childlike jokes, interesting adventures in a world created entirely by them, and create protagonists who are unrestrained and unconventional.

At the same time, they may be compensating for their unsatisfactory childhood life through writing, including the childhood trauma and pain they have experienced, and through their imagination to shape a more ideal self, and in the process of writing, they can regenerate their childhood selves. When we continue to delve into the "rabbit hole of the subconscious" from a psychoanalytic point of view, we can find that the creation of children's books may imply more expressions of desire.

When we talk about "children's literature", we must also avoid summarizing a general definition of representativeness in this controversial "literary category", because there are always various possibilities under the ceiling of "children's literature". But as readers and critics, we need to acknowledge that the appeal of "children's literature" to children and adults often comes from the shaping of childhood in these books, and the echoes of these stories with our individual experiences, expectations, and imaginations. After all, for many people, childhood is a time of constant savoring and nostalgia throughout their lives. Based on all the above discussions, I would like to propose a vision of a "Universal Child", a child image that encompasses the commonality of all people. When we go to read children's literature, is there a common aesthetic consciousness of human beings guiding us?

The critic Mei de Jong once explained the concept of returning to childhood this way: "Through all the deep, mysterious dimensions of your spontaneous subconscious, back to your childhood." If you explore deep enough, see enough authenticity, and become your childhood self again, you've probably become that Universal Child through your subconscious. "The study of children's literature is not only closely related to the various theoretical directions of literary research, but also helps all readers and writers to explore the inner self of us.

Resources:

1.James Kincaid, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) 140

2.James Kincaid, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature 140

3.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

4.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 106

5.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 197

6.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 97

7.Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, Children’s Literature: Criticism and the Fictional Child (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994)168

8.James Kincaid, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature 168

9.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 103

10.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 191

11.Spufford, Francis. The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001.

12. Roald Dahl Website

13.James Kincaid, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature 191

14.Julia Mickenberg and Lynn Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature 43

15.James Kincaid, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature 192