In a FoMC statement in January, the Fed mentioned that "soon" it would be "suitable" for a rate hike, making it clear that a March rate hike was coming, but powell repeatedly stressed in a press conference Q&A session that officials had not made any decisions, and said that the FOMC needed to remain flexible ("nimble") and did not rule out any choice.

Powell said, "We will make decisions based on the data that will be released next and the evolving outlook."

The statement creates an atmosphere of uncertainty for the market: How many times will the Fed raise interest rates this year? Will there be a sharp 50 basis point hike in previous meetings? The point in time of the shrink table? These issues remain unclear.

In a recent report, UBS analyst Jonathan Pingle noted that the January FOMC meeting highlighted nimble in answering which policy rate path is most appropriate, which means that in 2022 the Fed's monetary policy will shift from "new normal" to "flexible" and will accelerate the shift to "data dependence".

This sounds similar to Yellen's emphasis that rate hikes will be based on economic data, and seems to correspond to an earlier "discretion."

So, how to understand the Fed's "improvisational" new framework? UBS believes that this time is different from the "data dependence" of the Yellen era, so what is different? What does this mean for the market?

The new "adaptive" framework: the essence is still to maintain discretion

In addition to saying that interest rate hikes will begin "soon", the January meeting essentially abandoned forward guidance.

Powell first said at the press conference that he would not rule out the possibility of raising interest rates at each meeting, throwing out the most serious situation, but then Fed officials successively made speeches, and the style was more moderate and left room.

For now, basically all officials have hit back at a 50 basis point hike in March, with most officials seemingly hinting that there will be about four rate hikes this year, 25 basis points each.

Many officials also expressed a signal that the policy would follow the data:

Atlanta Fed President Bostic initially said he could raise rates by 50 basis points at a time if necessary, but then immediately "changed his tune" to say that a 50 basis point hike was not his preferred policy action in March; he said in an article in the Financial Times that he hoped to raise rates three times in 2022, but did not rule out other possibilities.

He added: "I think the message the chair wants to convey is that we are not on any particular track. The data will tell us what happened. ”

Minneapolis Fed President Neil Kashkarry said Jan. 28: "We hope that price pressures will naturally ease as supply chain issues are resolved, which means the Fed has to do less." Now, the commission has signaled that most officials believe there could be three rate hikes this year, about 25 basis points each. However, we must see the corresponding data. ”

San Francisco Fed President Daly said on Jan. 31: "More reference is appropriate. Assuming 4 rate hikes in 2022 and interest rates reach 1.25%, that's quite a bit of a contraction, but also a sizable amount of space left in the system because the neutral rate is 2.5 percent, which is still supporting the economy, not causing damage. I think that balance is the right way to deal with the uncertainty we face. ”

Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Haack said Feb. 1: "Can we raise rates by 50 basis points at a time? OK. But should we? I'm not quite sure about that right now... If inflation remains at its current level and continues to fall, I don't think there will be a 50 basis point hike. ”

UBS believes officials started with quarterly rate hikes, sidestepping the inference that the market raises rates at every meeting, retaining the option of accelerating or slowing down policies later.

UBS's current baseline forecast is that the FOMC will withdraw easing by raising interest rates by 25 basis points each quarter of the year (March, June, September and December) and begin shrinking its balance sheet at the FOMC meeting in May (or possibly no later than july).

However, the bank believes that this path will be highly dependent on data, especially inflation data and data that reflect the inflation outlook. Among them, the inflation data for May will be a watershed that will affect the direction of policy:

If the inflation data for the first half of the year (all the way through May) unexpectedly continues to rise, then in the second half of the year, the FOMC may shift from a quarterly rate hike to a pace of rate hikes at each meeting, and the June FOMC meeting may begin to signal a July rate hike, and then in subsequent meetings, as needed, raise rates by 25 basis points in a row.

Conversely, if inflation begins to weaken in the second half of the year, the FOMC may also pause rate hikes.

This suggests that the new framework retains the "flexible" options the Fed needs in the second half of the year, while essentially the Fed is still maintaining its discretion.

Is this time really different?

The Fed has avoided using certain fixed rules to constrain its monetary policy decisions, such as in the Yellen era, in order to maintain discretion, the Fed often pushed theory first, with innovative academic research results to constantly update the framework.

In the Powell era, especially after the outbreak of the epidemic, this tendency was even more pronounced. The media even used "Powell's Fed is like Greenspan's time" to describe Powell's emphasis on discretion and refusal to be disciplined.

But discretion has its drawbacks. Without a strong commitment, it is harder for the Fed to convince markets that it is serious about achieving its 2% inflation target.

However, UBS believes that the Fed's "data dependence" today is very different from the previous 20 years, and in Yellen's time as Fed chairman, although the Fed's policy has a very clear "data dependence", Yellen often said, "the policy did not follow the pre-set route", but the interest rate hike path at that time basically followed a stable and predictable pattern.

For example, in June 2015, San Francisco Fed President Williams said in a speech after the then FOMC meeting: "What does this mean for interest rates? As I said, policy is data-dependent. The speech began with "I can't tell you the exact date of the hike... But I can't..." end anyway.

But at that meeting, the Fed's median forecast for GDP for the fourth quarter of 2015 was 1.8 to 2.0 percent. The final result proved that the GDP in the fourth quarter was 1.9%.

This shows that the Fed at that time had a large control over economic data, and the Fed could set a policy path in advance, but this time it was really different.

Because in the new cycle of rate hikes, the predictability of the data is too low.

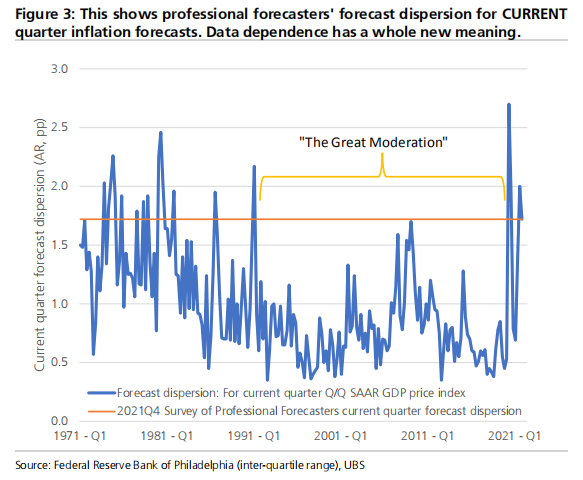

Taking the most critical inflation data, the recent Philadelphia Fed survey of professional forecasters on the fourth quarter of 2021 GDP deflator (a common measure of inflation) forecast dispersion, as high as the peak during the financial crisis. This increase in uncertainty is reminiscent of the years before the 1990s, decades before the so-called "Great Inflation Easing."

Analysts are divided on expectations for future inflation, and supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic are undoubtedly one of the disruptors.

In addition, some analysts believe that in contrast to the flattening of the Phillips curve during the "great inflation easing" period (referring to the decline in unemployment, which did not bring about an increase in the inflation rate), today's economic environment - the trend of globalization has reversed in 2008, the downward trend of capital factor prices is facing zero interest rate constraints, the global demographic dividend is gradually drifting away, the burden of aging society is getting heavier, monetary policy has also quietly reduced the weight of stable inflation, and monetary authorities are not only facing more complex trade-offs, but also need to carefully maintain their independence These factors are all forces calling for a return to inflation and the "resurrection" of the Phillips curve.

Today's Fed faces greater challenges, the economic outlook is more uncertain, and macroeconomic data is much more volatile. In the eyes of professional forecasters, even for the fourth quarter that has passed, the economic forecasts are very divergent.

Therefore, UBS believes that data dependence may be an escape in the "Great Easing" period, but data dependence is necessary in the current context. Given the wide range of uncertainties and data volatility, the FOMC has no choice.

There will be a risk of more instability in policy

While the Fed's new "improvisational" framework helps it respond in a timely manner to a variety of possible outcomes, to repeat the foregoing, discretion has its drawbacks, and for the market, this flexibility also means less predictability and possibly less regularity.

In addition, if central banks rely on data, which is more volatile than in recent history, it means that there is also a risk of more instability in policy, which also represents another source of macroeconomic volatility.

And UBS said the central bank's reliance on data on increased volatility would be part of a new macroeconomic era.

This article is from Wall Street Insights, welcome to download the APP to see more