Intellectuals have long played a persecuted role in Soviet history. However, this was not the case, and Soviet intellectuals were still treated very well throughout the Soviet period.

Perhaps because of the many good treatments enjoyed, the Soviet intellectuals were constantly divided and integrated, and some of the intellectual elite decided to explore the so-called "democratic freedom" channel and return the real history to the people. To this end, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, they even acted as "pawns" for the West.

In fact, in the original Soviet system, as the beneficiaries of the inherent interests, the Soviet army and the KGB did not welcome reform, believing that as long as the original system was maintained, excessive reform was completely out of the interests of this class.

According to a social survey conducted by the Soviet Academy of Social Sciences in early 1988, only one-fifth of government workers unreservedly supported economic reforms, while the rest of the investigators were skeptical of their success, arguing that even if they were to see results, it would be a distant matter.

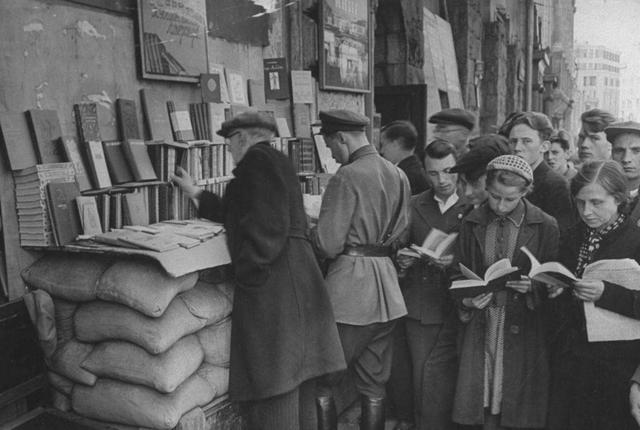

Instead, it was Soviet intellectuals who were zealous about reform. They not only supported reform, but also promoted the formation of radical groups, hoping to bring about political change in this way.

The reason why Soviet intellectuals were eager to change the status quo was closely related to the social situation in the Soviet Union at that time. On the one hand, intellectuals were greatly liberated during the Khrushchev period, and various underground organizations sprung up. The Soviet government, on the other hand, did not see the growing power of the intellectuals, who still paid attention to the so-called class principles when recruiting party members and neglected to include intellectuals in the highest strata.

As a result, with the development of higher education, Soviet intellectuals could only engage in general education, which made Soviet intellectuals who regarded themselves as social elites more and more dissatisfied.

Immediately after Gorbachev came to power, he implemented the so-called "liberalization of thought" policy, which brought great shock to the Soviet intellectual circles. However, unlike the original intention of the Soviet intellectuals to carry out institutional reforms, the reason why Gorbachev implemented the policy of ideological liberalization was actually to ask the Soviet intellectuals to give him suggestions and suggestions to promote the development of the Soviet economy. Eventually, however, intellectuals turned their backs on Gorbachev and buried the sprawling Soviet Union.

It is reported that Gorbachev's slogans of openness and new thinking once made the Soviet literati of the 1980s shine. The government's release of Sakharov, Sharansky, and other Soviet "ideology criminals" made the Soviet intellectual class cheer even more.

For a time, intellectuals seemed to be greedily breathing free and fresh air like "lifting the ban", and the public opinion and social atmosphere of the past also changed. Soviet intellectuals, who had been the object of criticism, even turned into members of the highest echelons of the Soviet Union. Some of them, like Abarkin and Afanasyev, were in high positions and served as deputy prime ministers of the Soviet government.

At that time, some veteran Soviet economists became advocates of a free economy, and the theoreticians of scientific socialism also advocated integration with the West, and it was not uncommon to point out that the phenomenon of swearing and forgetting ancestors was not uncommon.

Of course, the Westernized new generation represented by Heydar, Chubais and others was more radical in abandoning the Soviet Union. In the wave of privatization and Westernization, they advocated the transformation of the Soviet Union with the same set of Western capitalism, but they did not perform better. On the contrary, Abarkin, who was directly involved in the formulation of the economic reform program, did not exceed the level of Kosygin's reforms of that year, and the so-called "500-day plan" now seems to be nothing more than whimsical.

The bankruptcy of the Western idyllic dream left soviet intellectuals desperate, as if they had fallen into the ice hole of the free market overnight. At this level, intellectuals in the original sense no longer exist.

Throughout the period of Gorbachev's democratization, some intellectuals spared no effort in the anti-Soviet process, frantically accepting funding from Western forces and waving the flag for the Western camp. Through brutal political change and economic evolution, the former intellectuals have become fragmented, leaving only an empty shell.

Of course, the role of the "vanguard of freedom" in the West is not good. The wave of liberalization and national separatism that soon erupted shattered the Soviet intelligentsia to pieces. Overnight, former friends became enemies, and friends from the same hometown quickly divided. The political tide of strife also triggered confrontation and division in the Soviet intellectual circles, such as the phenomenon of writers fighting each other and teachers dividing school assets, which is not uncommon.

In summary, the tragic disintegration of the Soviet Union was more like a deliberate coup d'état. It was soviet intellectuals who buried reform, the powerful Soviets.