Zhang Yunfei

"We build new nations, just as we build new ships." Sun Yat-sen once compared the country to a steamship, and "great helmsman" was once a unique title for Mao Zedong. If people today carefully study the expression of ships in modern Chinese history, it is not difficult to find that ships as vehicles have become a unique image. Where the connotations attached to the ship come from, and how the complex conceptions of sovereignty, colonization, and the modern nation-state on the ship relate to the modern history of semi-colonial and semi-feudal China as a whole, Anne Reinhardt's new book, "The Course of the Great Ship: Shipping, Sovereignty, and National Construction in Modern China (1860-1937)" (hereinafter referred to as the "Direction of the Great Ship"), gives her own answer.

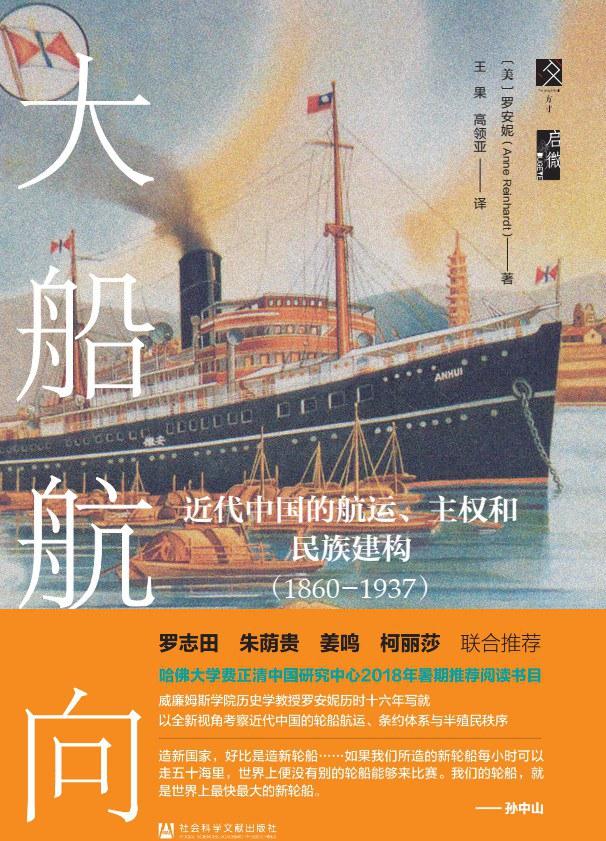

The Course of the Great Ship: Shipping, Sovereignty, and National Construction in Modern China (1860-1937).

Shipping Beyond Economic History: Problem Awareness and Research Trails

The book is based on Anne Rowe's doctoral dissertation, which was continuously revised and published in the United States three years ago. As a new book, "The Course of the Big Ship" does reflect a different sense of problems from its predecessors. At present, the academic circles have made fruitful research achievements on China's modern steamship and shipping industry, whether it is the corporate history centered on individual enterprises, the industry history that narrates the rise and fall of the shipping industry, or the perspective of the shipping industry on the official-business relations or industrial policies of the late Qing Dynasty, the aspects of modern economic history research are mostly reflected in the research field of the shipping industry. Compared with the research of previous generations, "The Course of the Big Ship" takes a different path. Although the authors still focus on the shipping industry, their concerns are not limited to economic history, but turn to a discussion of the "semi-colonial" nature of modern China.

The chinese inland steamship network of 1860-1937 was chosen as the object of study because the author believes that this object "best describes the formation of the semi-colonies" and the signing of the Treaty of Tianjin in 1860 led to the formation of this network, and the outbreak of the all-out war of resistance largely ended this shipping system. Further, the author divides two parts according to time, namely, the shipping of the late Qing Dynasty (1860-1911) from the signing of the Treaty of Tianjin to the Xinhai Revolution, and the shipping of the Republic of China (1912-1937) until the outbreak of the All-out War of Resistance.

The term "semi-colonialism" discussed in this book refers to diplomatic relations within the treaty system. Similar to her mentor Han Shurui's research on modern Chinese history from the perspective of culture, religion and society, Luo Anne also tends to approach Sino-foreign relations from a cultural perspective. Jumping out of the traditional research of the shipping industry, the author hopes to dialogue with scholars who are good at cultural studies and postmodern historiography, such as Shi Shumei and He Weiya. For "semi-colonialism", Shi Shumei highlights the differences between semi-colonialism, that is, because semi-colonial means that there is no monopolistic colonial entity, coupled with the pursuit of modernity and cosmopolitanism, modern China has formed a different literary expression from India. In contrast, Ho sees nineteenth-century British China policy as a "class" to guide the integration of non-Western countries into the modern capitalist world. In this regard, "all entities born in the age of empires are some form of semi-colonialism". It was from the differences between the two that Roanne found her own sense of the problem. If the two views are based on two different understandings of colonialism, the former attributing it to a mode of domination, while the latter seeing it as a model of power and knowledge, the "hegemonic project". Roanne did not choose either of them, but examined the hyphen between "semi" and "colonialism", that is, the shipping industry examined the connection process between China and foreign countries, highlighting the complexity of "semi-colonialism". That's what the book is all about. The word "semi" means the limited sovereignty of modern China and the mechanism of cooperation with the great powers through the treaty system, which is the uniqueness of semi-colonial as a way of ruling; while "colonization" is embodied in racial and class privileges in social space and nationalism as a driving force for decolonization, which is the universality of (semi-) colonization as a discourse of power.

While previous commentators have spoken of the uniqueness of semi-colonialism, often emphasizing the multi-headed control of China by the great powers over China and the limited sovereignty of China, the authors point to another, more specific form of semi-colonialism, namely collaboration, using shipping networks as an example. The concept comes from Ronald Robinson, who emphasized the interdependence of native collaborators and imperialist forces. The author hopes to avoid moral judgments such as "agents" and "foreigners' court" and focus on specific cooperation mechanisms. This book takes the formation and evolution of this "cooperation" mechanism as a clue and arranges the layout in chronological order. The first part (chapters 1 to 3) focuses on the formation of China's inland shipping network in the late Qing Dynasty. In the first chapter, the author uses the archives of the Prime Minister yamen and the Archives of the British Foreign Office to take the formulation and implementation of treaties and shipping policies as clues to show the sovereign operation of the Qing government against inland shipping after the Second Opium War and its restrictions. It is worth noting here that the author, by comparing the North China Victory, the British Foreign Office archives and the Prime Minister's Yamen archives, found that the differences between British businessmen in China are closer to an "expansionism", the latter tends to follow the treaty system, and the North China Victory newspaper moralizes the Qing government's resistance as a resistance to technology and even makes a paternalistic interpretation compared with the Luddites in the British Industrial Revolution. This view has a profound impact on the historical narrative of the aftermath. However, what Li Hongzhang and other senior officials are concerned about is that the traditional order will not disintegrate, and "it is neither moralism nor sentimentality." In chapters two and three, the author reconstructs the market conditions of China's insider shipping in the 1870s by using the corporate archives of Swire, Jardine Matheson and China Merchants. Before the 1880s, Chinese businessmen mostly invested in foreign shipping companies in the form of attached shares to seek refuge. With the global communications revolution and the Qing government's intervention in inland shipping with the steamship merchants bureau, the shipping market competition became increasingly fierce, and two steamship companies, Swire and Jardine Matheson, chose to establish a liner association with the steamship merchants bureau to resist external competition and protect the market share of internal members by delineating routes and limiting minimum freight rates. Until the Sino-Japanese War, this mechanism was at the "center of the industry". By dividing up the operations of the three companies and the operation of the liner association, the author highlights the "cooperation" implication of this compromise and cartel-style union. It should be noted that "the guild boosted Britain's expansion plans while helping the China Merchants fleet become a symbol of local sovereignty". For the steamship Merchants Bureau, this cooperation abandons the so-called "commercial war" and the attempt to recover the right to profit, and the superficial "regulation competition" actually provides conditions for British companies to use the advanced shipping resources and manufacturing base of the home country, making the differentiation of the three companies within the guild increasingly obvious. On the other hand, stable profitability and the relaxation of competition have provided a stable income guarantee for the steamship Merchants Bureau, enabling it to cope with the frequent changes in official-business relations and demand from many parties.

Part II (Chapters 5-7) focuses on changes in China's inland shipping network during the Republic of China. Although the treaty system still existed after the Xinhai Revolution, the central government, as a "collaborator," lost control of the localities. After the Sino-Japanese War, Japan's shipping industry continued to expand due to government subsidies. The addition and withdrawal of nissin Shipping's camera to the liner union indicates a marked decline in the mechanism's control over the shipping industry. More importantly, Chinese nationalism and resistance to the great powers are gradually emerging, impacting the original cooperative mechanism. The fifth chapter focuses on the three "national capitalists" Zhang Xiao, Yu Qiaqing and Lu Zuofu, and cuts into the discussion of shipping nationalism. The absence of state power in the early Ming Dynasty actually weakened the shipping privileges of the great powers, and Zhang, Yu, and Lu took advantage of the trend of shipping nationalism to join the competition of inland shipping from regional shipping businesses. Chapter VI begins with State intervention in the shipping industry. Through the comparison between Nanjing (the Nationalist government) and Chongqing (Liu Xiang), the author describes two paths to decolonization. The former struggled with diplomatic pressure to reclaim the right to sail, and the industrial policy towards the shipping industry led to the marginalization of private companies, while the latter used the independence of the southwest more flexibly to promote the expansion of Chuanjiang shipping by Minsheng Company.

Second, the complexity of "semi-colonialism" in modern China is also reflected in the universal colonial discourse and power, and chapters 4 and 7 reveal the underlying colonial ideas in the shipping industry by treating steamships as social spaces. There are currently ten book reviews of the book in English academic circles, most of which focus on Roanne's social spatialization of ships, of which Tim Wright believes that the "tea house crisis" is the most attractive part of the book, showing the management limitations caused by the widespread resistance faced by the Chinese powers, and Isabella Jackson considers this part the most interesting. In fact, from teahouses, parks, horse racing halls to department stores, it is not uncommon for modern and contemporary Chinese historians to borrow social space theories, while Luo Anne reflects the universality of (semi-) colonization as a kind of knowledge and power through the social spatialization of steamships, which contrasts with the above-mentioned cooperative side. In addition to the transfer of problem awareness, "The Course of the Great Ship" is another reason why "The Course of the Great Ship" can avoid becoming a footnote of its predecessors.

The fourth chapter explores the formation and operation of social space in Chinese steamships in the late Qing Dynasty. Starting from specific aspects such as employee situation, cabin design and ticket pricing, the author reveals that it is the business formats of steamship enterprises and the shipping industry that shape and consolidate the racial and class privileges that prevail in ship sailing- ships in China are generally outsourced through compradors, and the cooperation mechanism of liner associations promotes institutional isomorphism of the entire shipping industry. This "principal-agent relationship" with the compradors has led to increasing confusion in the Chinese cabins, while foreign crew members are not impressed by this situation. The monopoly of shipping knowledge and the discriminatory pricing of insurance premiums have made the technical positions on ships monopolized by foreigners. The design, pricing of ships, and the zoning management model of Chinese and foreign cabins all reflect racist positional assumptions. In addition, the author presents three different boat ride experiences through the personal materials of Chinese and foreign passengers (reports, travel notes, travel logs), illustrating the specific perception of individual colonization: foreign passengers deepen their prejudice against Chinese, local literati lament the lack of management of Chinese cabins but no one cares about the "isolation", and the class differentiation of passengers has become a typical expression of nationalist accounts.

Tianjin inland river transportation at the end of the Qing Dynasty

In chapter seven, the author examines the diachronic changes in this social space. At this time, the National Government in Nanjing improved the certification mechanism for shipping practitioners and the foreign ships also suffered from the high salaries of foreign employees, making the racial and skill boundaries on the ships increasingly blurred. Due to the structural contradictions of outsourcing services and racial prejudice against Chinese, foreign ships have been unwilling or unable to focus on reforming shipping, and due to the institutional homogeneity and path dependence caused by liner shipping associations, the state-run steamship merchants bureau has also been unable to reform management. However, minsheng company as a late-rising local shipping company, Lu Zuofu's "new ship" replaced the original three-pack system by using a vertical management model, and the tea houses recruited by the compradors were officially incorporated into the company. In addition, Lu Zuofu not only attaches importance to passenger transport services, but also emphasizes the education of passengers, making them adapt to a modern and civilized boat experience, thus reconstructing the social space in the ship. Further, the authors also use Minsheng as a kind of social space, that is, the company is not only profit-making motives but also has disciplinary effects on employees/customers, making it an element of adapting to and promoting social change. Among them, the introduction of Taylor system and collectivist management is inseparable from Lu Zuofu's non-economic pursuit as a so-called "national bourgeoisie". More importantly, Lu Zuofu proves that the segmentation of the shipping industry stems more from inertia in business operations than from a priori racial defects. So far, taking Lu Zuofu's "New Steamship" as a case study, the author depicts the diachronic process of "steamship" and shipping networks from the initial colonial/anti-colonial products to a kind of indigenous modernity, which is based on modern Chinese nationalism, which is the key to the decolonization of China's steamship and shipping industry.

It is worth mentioning that the last section of each chapter is accompanied by a comparison of the Sino-Indian shipping industry. Unlike China, India has no local enterprises to compete with foreign ships due to complete colonization, let alone a similar cooperation mechanism. On the other hand, India is similar to China – on a ship, Gandhi's experience of "segregation" is also reflected in the accounts of a group of Chinese literati, and the decolonization of the shipping industries of the two countries is also driven by nationalism, with the independent regime's alternative industrial policy as the end – through the contrast with india as a colony, the complexity of semi-colonialism in modern China has been further reflected.

Ripening for a Living: Evaluation and Limitations

As the author points out, the book emphasizes the mechanism of commercial and political cooperation between Chinese and foreign shipbuilding enterprises and the shipping industry in semi-colonial China, "rather than as a specific individual or group of collaborators", so although the book focuses on the grand and abstract concept of "semi-colonialism", it is useful through the use of steamships as a method. Second, this orientation enriches the research perspective of the shipping industry. In fact, it is not limited to this book, and the current trend of global and cultural shifts in overseas academic research is clearly reflected in the study of corporate history and industry history. Shortly after the book came out, Bikos placed Swire in Hong Kong, Chinese mainland and linked it to the global business industry, both continuing Anne Rowe's discourse and paying special attention to Hong Kong in Sino-British interaction. Taking transportation as the research object, Li Siyi explores the cultural experience and time and space imagination caused by the railway with the method of cultural research. Not only that, but for colonial and semi-colonial studies, this book uses specific trades as a case to reduce the tension in previous research, showing the complexity of the "semi-colonial" order. Although the views seem to be reconciled, as the author puts it, this book "does not intend to fully illustrate the forms of semi-colonialism." Because shipping is only an element of the semi-colonial order, yet it provides a concrete case."

New Hankou Wharf in the early years of the Republic of China

However, there are still some shortcomings in this book. From the perspective of corporate history or industry history, this book does not list any data or charts. In the light of the (semi-) study of colonialism, such characteristics are beyond reproach. However, regardless of the formation and transformation of Chinese businessmen's shareholding or the liner association, the perspective taken by the author can still be attributed to the history of enterprises or industries. The formation and operation of cartels is itself a collective action. Although the author mentions that the power of the three companies has been growing, it does not give data on how the competitiveness and bargaining power of the three companies have changed, so why there is no motivation or behavior of members within the cartel to default, compared with the flexibility of the Nissin Mail Shipping Society, Swire and Jardine Lack of in-depth explanation of the maintenance of guild rules. If the orientation is related to the opening of the door or the policies of the great powers toward China, the author should also add relevant content. If we criticize, the author's discourse space is actually limited to the Yangtze River Basin, which naturally belongs to the core area of china's shipping industry in modern times. Because of the issues involving sovereignty and ethnic construction, Japan's expansion of the shipping industry in the northeast, north China, and Bohai Bay cannot be ignored. In addition, whether Liu Xiang's governance of Sichuan River shipping is only an isolated case also requires more regional analysis and comparison.

Secondly, in terms of materials, the author makes use of a number of corporate and government archives scattered in Chinese mainland, Taiwan and the United Kingdom, especially the archives of Swire and Jardine Matheson, and refers to the common historical materials of past shipping industry research. However, the credibility of specific historical materials is still worth considering. For example, many of the examples chosen by the author of minsheng's "new ship" come from the company's publication New World. The author once emphasized how social space is "perceived and interpreted by users". She did choose many passenger accounts as an argument, but for example, whether the travelogues published in "New World" are advertising or documentary statements needs to be more deeply distinguished.

In the face of similar new books, readers often praise their writing style and problem awareness. Throughout the reader's comments on the book, Roanne's unique vision of "using the steamship as a method" and her precise stepping on numerous academic topics have received many praises. However, if we can clarify the author's writing framework and argument logic, it is not difficult for readers to find that the current research results of Chinese academic circles on Sino-foreign relations, social space and shipping nationalism are not uncommon. The reason why "The Course of the Big Ship" can make readers feel new is more due to the author's unique problem awareness and research path. For example, the clever choice of the liner guild makes the seemingly grand and abstract "semi-colonization" come into practice. The author is "turning maturity into a living" and "using ships as a method" rather than a direct research object, thus stringing together a series of common sub-topics with semi-colonial themes. This keen vision, unique sense of problems and flexible writing ideas are the places where this new overseas sinology book attracts people's deep thought.

Editor-in-Charge: Shanshan Peng

Proofreader: Yan Zhang