Art and science are opposites in many ways, but are they really just going their own way? Luisk Mangjean's research points out that this is far from the case: the same part of the art that moved us in the past has scientific knowledge, such as the birth history of wild eggplant, or van Gogh's sunflowers that look like pompoms.

Written | [french] Luvac Mangjan

Excerpt from | Anya

Art and Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake, by Lo c Mangin, translated by Xinhua Chen, Chongqing University Press, February 2022.

In the 6th and 7th centuries AD

Eggplant is not popular

In Turkey, there is a belief that dreaming of three eggplants is a sign of good fortune. Also in this country, people are proud to invent a thousand recipes that feature it. This prestige reflects the region's deep-seated perception of the vegetable. Was it domesticated? This is a difficult question to answer because describing the history of humanity appropriating a particular wild plant for itself has rarely succeeded, except through genetic analysis or when people have access to multiple samples.

In many vegetable cases, experts are tired of guessing because they lack information, especially archaeological proof. However, Wang Jinxiu of the Institute of Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and Sandra Knapp of the Museum of Nature in London succeeded in reconstructing the stage of domestication of eggplant (cultivated solanum). By what means? They consulted a wealth of examples from ancient Chinese literature as well as illustrations about this vegetable. They reveal the process of domestication and three main characteristics of Chinese vegetable farmers.

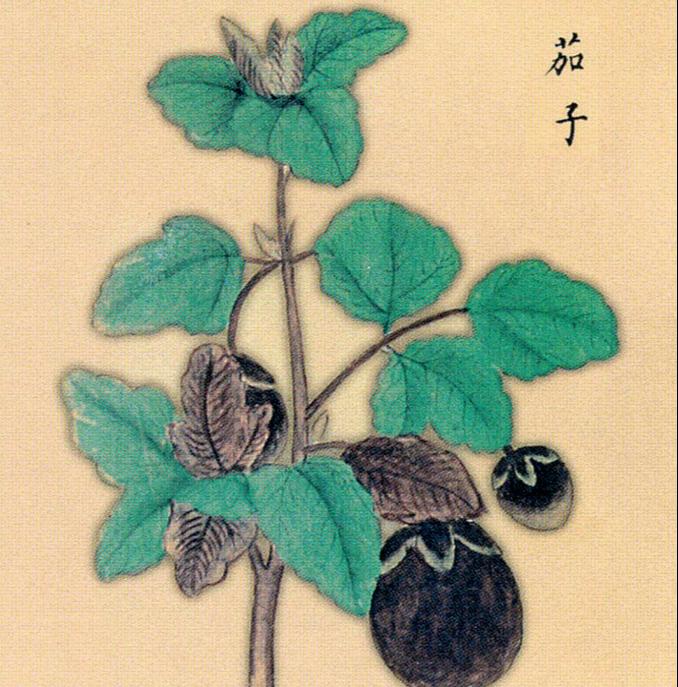

Anonymous, Materia Medica, 1220. (Illustration of Art & Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake)

In the early 1990s, Richard Lester, an agronomist at the University of Birmingham, and his colleagues proposed that eggplant is a derivative of the wild variety Solarum incanum, a plant that grows in North Africa and the Middle East. It started as a decorative plant, and then was selected by Asian cultivators on several "journeys" between East and West.

In addition, we are not familiar with the domestication of eggplant, and several regions are regarded as birthplaces: India, southeast china, Thailand, Myanmar... It is in this regard that the Chinese literature plays a role. These documents are so long and endless that it means that we have works from all eras, and they are coherent. In these botanical books, historical archives, agricultural manuals, local chronicles, and books (various encyclopedias) – such as the Imperial Encyclopedia of Ancient and Modern Books and the Siku Quanshu – we find numerous records of eggplant. In total, 75 books came in handy. What do we learn from this?

First, the oldest evidence of eggplant exists in the Covenant of The Servants, which was written by a man named Wang Bao in 59 BC. Thus, during this period, eggplant was already domesticated, especially on the Chengdu Plain, located in southwestern China. They then exhibited the traits that the selectors had cared most about over the centuries: size, shape, and taste. In the 6th century AD, according to the Qi Min Zhi Shu, eggplant grew very small. In 1069, the first known painting of the vegetable appeared in the Materia Medica: the fruit in the picture was round and the crop had no thorns. Less than 200 years later, in 1220, on an illustration in the Rock Materia Medica, we can see purple-red eggplant, which is longer and larger than the previous eggplant.

Later, in the 16th century, Li Shizhen depicted eggplants with a diameter ranging from 7 cm to 10 cm in the Compendium of Materia Medica. In 1726, the Chronicle of Jiangxian County mentioned an eggplant weighing more than 1.5 kilograms! As a result, the eggplant selected by Chinese cultivators is getting bigger and bigger. Until the 14th century, Chinese eggplant was round. They become longer only after that, as we see in the Compendium of Materia Medica. In 1609, the Three Talents Picture Society also depicted ovoid-shaped fruits. In the Ming Dynasty a century later, many kinds of eggplants were bred, round, ovoid, long, thin... In 1848, the famous botanical treatise "Botanical Names and Real Tu Kao" depicted the most widely distributed eggplant.

Illustrations of eggplant in ancient Chinese literature (Illustration of Art and Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake)

Bibliographic resources also present the evolution of eggplant flavors. In the 6th and 7th centuries AD, eggplant was not popular, but it was improved and became "delicious" in the 9th century. After that, Huang Tingjian wrote several poems praising the taste of a white eggplant, which can even be eaten raw, but it does not work today (because of the discovery of saponin).

Therefore, China should be the birthplace of the eggplant we eat today. In addition, With as many as 200 endemic eggplant species, China is the first world eggplant producer, producing 16 million tons per year (more than 50% of global production). Another conclusion that can be drawn from these findings is that, in addition to archaeology and genetics, the study of plant domestication has since had a third pillar – bibliography.

Some of the sunflowers painted by Van Gogh

Looks like a pompom

On 20 February 1888, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) settled in Arles. In August of that year, he painted the first painting in the Sunflower series. In January 1889, he completed three more paintings, and by this point the four-painting series was completed. Each time he painted, he would put 3 to 15 sunflowers in a bottle, which was placed on a yellow or blue base cloth. Some were originally used to decorate the rooms of Paul Gauguin, who had come to meet the Dutch painter before 1888. In addition, one of Gauguin's works depicts Van Gogh painting a bouquet of sunflowers.

The latter may have been a painting in the Vase and 5 Sunflowers series, destroyed in an air raid in 1945. Each time, Van Gogh's sunflowers are in a different stage of growth, from flowering to withering. However, they are also morphologically distinguished. In fact, some sunflowers look like pompoms! For example, in the paintings of the National Gallery in London, we can see seven pompoms. John Burke and his colleagues at the University of Georgia in Athens are concerned with the genetic basis of this appearance.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Sunflowers (Illustration in Art and Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake)

Before describing their results, let's talk in detail about the anatomy of the sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Sunflowers belong to the Asteréracées (formerly written Comprosées), which is the largest plant family (Jerusalem artichoke, dandelion, daisy, artichoke...). )。 The flowers of the sunflower, known as the flower-leaf ornament, are concentrated on the head-shaped inflorescence (a fleshy flower tray). Thus, what we call the "flower" of a sunflower is actually made up of a large number of real flowers, i.e. flower and leaf ornaments gathered on a head-shaped inflorescence. On the common sunflower, the surrounding flower and leaf ornaments are tongue-shaped, that is, they all have small tongues (tongue pieces, we mistake it for petals), while the central flower and leaf ornaments are tube-shaped, tube-shaped; only the latter has reproductive organs.

Pompom sunflowers are heavy-petaled flowers. In Letters from the Mountains, written in 1764, Jean-Jacques Rousseau described the following phenomenon: "A heavy-petaled flower is a part of a flower that exceeds its natural number... The word "heavy-petaled flower" does not simply mean an increase in the number of petals, but an arbitrary increase. "In the heavy petaled flowers of sunflowers, in the case of the common type, the wild sunflower, although not integrally, at least a few rows of flower and leaf ornaments with tubes are tongue-shaped. John Burke's team wanted to understand the mechanics of these heavy-petaled flowers.

These mechanisms begin with hybridization between wild-type sunflowers and other heavy-petaled flower types. The results conformed to the laws established by Mendel in the mid-19th century, nearly 20 years before Van Gogh painted his sunflowers. The characteristics of the heavy-petaled flowers are caused by a mutation in a single gene, and this mutation is decisive. Other hybridizations show a second mutation in the same gene, which is a recessive mutation: it is expressed by a special type of flower and leaf ornament: they are yellow-colored tubes with reproductive organs.

In other words, they are an intermediate product of tongue-shaped flower-leaf ornaments and common sunflower-tubed leaf ornaments. Geneticists identified the relevant genes and sequenced them: this is the HaCYC2c gene, which encodes transcription factors, which are proteins that contribute to the expression of other genes. The HaCYC2c gene family involves symmetrical control of the mouth organs. In the case of a heavy-petal flower, the mutation is a nucleotide inserted into a gene promoter, which is thus expressed in an abnormal way in the central flower ornament. In the second example, the mutation originates from a transposon (the active part of DNA) entering the gene itself and preventing it from being expressed in all the flower and leaf ornaments.

Common Sunflowers and Heavy-petaled Sunflowers and the Construction of Sunflowers (Art & Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake illustration)

Van Gogh's paintings do not have a later type of sunflower. Didn't he see it? Or do you think it's not beautiful enough? Neither history nor the Letter to Theo has a single word.

Why are the watermelons that have conquered the world white?

You should remember last summer. Céline, Catherine, Alana, and a guy named Sugar Baby... Make no mistake, what is said is... A variety of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). This cucurbitaceae is one of the most refreshing of all fruits, and Mark Twain has his protagonist in The Tragedy of Wilson the Fool say that watermelon is "the king, and it is given by God, and it is the king of all fruits." Take a bite and you'll know what the angel is enjoying."

Such luxuries are only worthy of the courtesy of the painter, and in fact we can find quite a few paintings of watermelons, such as in a still life painting by Flamand Abraham Brueghel (1631-1690), or in a work by Giovanni Stanchi (1608-1675) in Italy. On the painting of the latter, we can find at least two watermelons, but they are very different from those of your summer. However, in today's varieties, one can find the red melon flesh – which is natural – as well as green and beige, but in the paintings, the inside of the melon is predominantly white, with only a little red. How should it be explained?

Giovanni Stanchi (1608–1675), Watermelon, Peach and Pear in a Landscape (Art and Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake, illustration)

James Nienhuis, an agronomist at the University of Wisconsin, was interested in the issue. First of all, let's not forget that the main part of the pulp of a watermelon is the overdeveloped placenta in which the seeds are hidden, and the placenta binds the ovary of the plant (before fertilization). In James Nynchius's view, today's watermelon comes from this selection, which is implemented by cultivators in order to obtain an increase in the concentration of lycopene (a red pigment that we can also find in tomatoes), resulting in a very red pulp.

Then, the watermelons that appear in Bruegel's still life are not only beautiful, but also very red, the same era as Steinchi's paintings. Is the Italian's watermelon ripe? Yes, the existence of the black seed is unquestionable: the fruit is picked when it is ripe. This diversity indicates that the selection process that is taking place in this century is aimed at obtaining the ideal watermelon. It continues today; the new varieties of "seedless" (or more precisely, shrinking seeds) we see in the store are testimony to that. This trait comes from a triploid (plants have three sets of chromosomes instead of two). Densuke black watermelon, which grows only in northern Hokkaido, Japan, is also the most recent variety. Its rarity and taste make it invaluable: every sample is worth thousands of euros!

Even though watermelons conquered the world (people produce hundreds of millions of tons a day), little is known about its source. In other words, the question is knowing how long the angel has been eating watermelon. According to Harry Paris of the Centre de Recherches Newe Ya'ar in Israel, they have been enjoying watermelon for at least five thousand years.

By bringing together all the historical clues, he finally reconstructed the history of watermelon. The oldest archaeological remains, the watermelon seeds, were found in Libya. Seeds and paintings have also been found in egyptian tombs for four thousand years. Surprisingly, one of the pictures depicted a rectangular fruit that resembled today and was also different from a spherical wild variety with a bitter taste. Therefore, the Egyptians grew watermelons. The ability to store water is a winning formula in dry areas. Undoubtedly, this explains why watermelons appear in tombs, because the dead also need to quench their thirst during their long journey. Paris deduced from all this evidence that watermelons appeared in North Africa and were domesticated there.

Some writings indicate that watermelons then left their birthplace and spread around the Mediterranean. In the 1st-century Naturalist, Pliny the Elder boasted about the heat-reducing effects of watermelon. Doctors Dioscoride and Hippocrate similarly praised its efficacy.

This article is selected from "Art and Science: From Wild Eggplant to Issey Miyake", which is slightly abridged from the original text, and the subtitle is added by the editor, not the original text. The illustrations used in this article are from the book. It has been authorized by the publishing house to publish. Original author: [French] Luvac Mangjang; Excerpt: An Ye; Editor: Qingqingzi; Introduction Proofreader: Liu Jun. Without the written authorization of the Beijing News, it shall not be reproduced, and welcome to forward to the circle of friends.