One

One evening at the end of October 1948, the Chinese People's Liberation Army surrounded the ancient capital of Beiping, which was defended by Fu Zuoyi's troops, and the siege campaign was about to break out. In the midst of this rumbling and panicking season, in the living room of an ordinary family in the city, several men were talking about something that had nothing to do with the war and situation in front of them, that is, how to write a dictionary that was truly suitable for the public. borrow

Helping the dim lighting of the living room, acquaintances can vaguely identify these people called Zhou Zumo, Wu Xiaoling, Zhang Keqiang, Jin Kemu, and Wei Jiangong. They were colleagues, professors at Peking University, and they were all leading linguists in China at that time. Compared with the cannon fire outside the city that determines the fate of the nation, it is undoubtedly a trivial matter for several scholars to talk about how to write a small dictionary. However, looking at the long river of China's historical and cultural development as a whole, this is indeed a far-reaching "major event". The initiator of this incident was the owner of this room, the scholar named Wei Jiangong.

Wei Jiangong, born in 1901, studied under Mr. Qian Xuantong, a master of chinese Chinese dialects and a professor at Peking University, who has profound knowledge of phonology, philology, exegesis, and classical philology, and is also very avant-garde in the transformation of traditional culture. He strongly agreed with the "Chinese Movement" advocated by the May Fourth New Culture Movement. The so-called "Chinese movement" is nothing more than two directions, namely, "consistency of speech" and "unification of Chinese". "Consistency of speech and text" means that the written language is not used in ancient chinese, but in modern vernacular; "Chinese unification" means that modern vernacular should be the Mandarin of Beijing dialect as the national common language. From the age of thirty, Wei Jiangong actively promoted the sport and demonstrated amazing professional talent and organizational skills. At the age of 27, he was appointed as one of the seven members of the Standing Committee of the "Preparatory Committee for the Unification of Chinese" of the Ministry of Education of the National Government. In 1945, he was sent to the island of Taiwan, which had just escaped Japanese rule, where he vigorously pursued the Chinese movement for three years, making Taiwan the first region in the country to promote "Mandarin". In October 1948, he returned to the motherland where the two parties and two armies were about to fight a decisive battle, quietly waiting for the advent of a new society. Of course, his mood is very unstable.

In Wei Jiangong's eyes, the results of the "Chinese Movement" that began in the early 20th century are gratifying. At the very least, writing and communicating in the vernacular has gradually become a social habit. Consistent words and texts have become the mainstream consciousness of readers. However, in the face of the increasingly popular vernacular environment, a widely applicable language tool has not been available. Common dictionaries often have shortcomings such as heavy text and light language, language reality that is divorced from the vernacular environment, interpretation is copied and copied, and there is a lack of scientific analysis of language. Take the "Guoyin Dictionary" published in 1948 as an example, which notes the "knife": 1. A sharp weapon for cutting and cutting. 2. The name of the ancient coin, which is called in the shape of a knife. 3. Boats. For example, "Whoever said he was wide, he did not tolerate a knife", see The Book of Poetry. This annotation has two drawbacks: first, the interpretation is still expressed in the vernacular rather than the vernacular that has become popular in society; second, the last two interpretations of "knife" belong entirely to the context of Old Chinese and are almost unused in the actual popular language.

For intellectuals of moderate education in general, especially more people who have just emerged from illiteracy, there is an urgent need for a novel, fresh, simple and practical dictionary to serve as a "silent teacher" for their daily learning. In the view of Wei Jiangong and others, the emergence of this book will directly affect a nation's cognition of the mother tongue and will further affect the state of the overall national quality of a country. From this point of view, the significance of the small gathering in the Wei family's living room was as important as the sound of cannons outside the city wall. Mr. Jin Kemu, one of the parties involved, fondly recalled many years later, "We drafted the idea of a new dictionary in the hall house of the Wei family. ...... The sound of gunfire coming from outside the city seemed to give us a beat. We could not have imagined the future of the dictionary we had, but we had a belief that China's future lay in the hands of children and illiteracy, and that the danger lay in ignorance. Language and writing are tools for universal education. Dictionaries are tools for language and writing. We have nothing but to chew on the words. Talking about dictionaries is talking about the future of China. The sound of the cannon makes our confidence grow. ”

Just as Wei Jiangong and others were carefully discussing the style and structure of this future dictionary, there was another person who was also planning this matter. He is Ye Shengtao, a famous publisher, writer, and educator on the mainland. Ye Shengtao pays attention to language reference books, first of all from the perspective of an old qualified publisher. As early as August 1947, when he presided over the Shanghai Enlightened Bookstore, he expressed doubts about the Xia's Dictionary (edited by Xia Junzun and Zhou Zhenfu) published by his bookstore, "There is not much excellence, and it is not convenient for beginners." Although it will be published on the market, it is afraid that it will not sell well. He once suggested another small dictionary, and started to make several dictionary samples, agreeing on the style, but later gave up for some reason. With the keen eye of a publisher, Ye Shengtao perceived that dictionaries could not win the market because they were "not easy to learn". In his diary years later, he made the question clearer. In July 1952, the new dictionary was still not available, but the social demand was already unprecedentedly vigorous, "the culture of learning was very popular, the peasants were required to be literate after the land reform, Qi Jianhua accelerated the implementation of the literacy method, and the factories and troops have passed on the study." After literacy, you need to read books, and reading books requires a dictionary. When people picked out two dictionaries from the market for Ye Shengtao to review and identify, he found that the problems were still the same, "However, looking at these two volumes, there are many problems, or they cannot give the reader obvious concepts, or the language is not clear, although it is not wrong, it is not all right, or the language is difficult and difficult for the reader to understand." In short, beginners get it, and they think they have to rely on it, but in fact they fail to solve the problem, or only between solving it and not solving it. When there are more than a hundred kinds of small dictionaries in the market, everyone copied and copied them, guessing that they were all such ears. Publishers like to come up with small dictionaries, regarded as commodities, and failed to think much about readers. Obviously, as a publisher with a strong sense of social responsibility, language and writing scholars such as Ye Shengtao and Wei Jiangong have paid attention to the same problem, that is, in the face of the rapid popularization of native language scripts, the lack of practical language tools has become a "bottleneck" that must be broken.

Two

The cannons on the land of China are sounding, and the smoke of gunfire is fading. Wei Jiangong became the first head of the Department of Chinese at Peking University after the founding of the People's Republic of China, and Ye Shengtao, as deputy director of the General Administration of Publishing of the Central People's Government and president of the People's Education Publishing House, began to live in the same city as Wei Jiangong. At this time, the new regime was in ruins, and there was an extreme demand for workers with a certain level of education in various positions. As a result, as Ye Shengtao said in his diary above, great enthusiasm for learning has been released throughout Shenzhou, and people have to get rid of blindness, read and learn culture. The old dictionary is naturally "inconvenient for beginners", and for the newly established socialist regime, the old values attached to the old dictionary can no longer be popular. In this way, writing a new universal dictionary became an imperative.

The planner and organizer of the compilation and publication of the dictionary was, of course, Ye Shengtao. He had both the role of a publisher and a government official. The burden of the editor-in-chief of the dictionary fell on Wei Jiangong. This story is also very legendary. When Ye Shengtao asked Wei Jiangong in March 1950 if he would be willing to compile a dictionary, the scholar couldn't help but agree. It's just that he is worried that the position of head of the Department of Peking University that he holds will inevitably have to restrain his energy and do not know how to get rid of it. Ye Shengtao was also very straightforward, and quickly revised a letter, imploring the then chief of Peking University to revoke Wei Jiangong's position as head of the department and only retain his teaching position. As a result, Wei Jiangong was able to throw his "unofficial body" under Ye Shengtao's tent. However, having just stepped down as the head of the Peking University Department, he was appointed as the head of a small organization, that is, the president of the Xinhua Dictionary Society. This historically little-known institution, attached to the Then Editorial Board of the General Administration of Publications, was very small. During its existence for more than two years (1950-1952, later became the Dictionary Editing Office of the People's Education Publishing House), it devoted most of its time to only one business, namely, to write the Xinhua Dictionary named after it. When Wei Jiangong took office, the dictionary was short of people, only the eight pages of pale yellow bamboo paper he carried in his pocket. On the paper, the letters were neatly written, and he had consulted with Jin Kemu and other friends for the past two years to formulate the "Editorial Dictionary Plan". The "Plan" summarizes the ten characteristics that this new type of reference book should have: it is compiled on the actual linguistic phenomena; it is shaped by sound; it is arranged by meaning; it is divided by language; it is determined by meaning; it is widely collected in living language; it is sought by sound; words are selected by meaning; it is suitable for the public; and it is selected as an appendix. Facts have proved that the ideas on these pieces of bamboo paper are almost all realized in specific operations. The blueprint for the compilation of the Xinhua Dictionary was already brewing and maturing in the minds of scholars long before the birth of New China.

At most, only a dozen people participated in the compilation of the first edition of the Xinhua Dictionary of the Xinhua Dictionary. But for such a significant dictionary, every participant was extremely engaged. Taking Wei Jiangong, the oldest qualified, as an example, when he was more than half a hundred years old, he insisted on teaching at Peking University while taking time to rush to the society to preside over the compilation of dictionaries. Due to the tight schedule, he often took the manuscript home to review. As for the remuneration, not a penny is needed, and it is completely obligatory. The codification process is a collective responsibility system, where each word is written separately on a small card, on which the writer writes the entry and stamps it as a sign of responsibility. Then everyone read it to each other, and wrote the opinions on the cards and stamped them. In this way, after the card is circulated and discussed, the entries of the word in the dictionary are summarized and copied. It stands to reason that with such a professional team and such professionalism, compiling a high-quality dictionary is just around the corner, but the truth is not so simple.

The work of the "Xinhua Dictionary" was officially launched in August 1950, and the original plan to publish the Xinhua Dictionary within one year was not achieved. After postponement, it was required to be revised and completed in June 1952, and published at the end of the year, but it was still frustrated and postponed again. It was not until December 1953 that the first edition of the Xinhua Dictionary was finally completed. In the summer of 1951, the first draft of the dictionary had been completed on time, and when it reached the hands of the final reviewer, Ye Shengtao, the expert leader affirmed that "the dictionary compiled by the Dictionary Society is not yet a perfunctory work, one case after another, all with thought", but still felt that its popularity was obviously insufficient, "only it was not exempt from being biased towards the expert point of view, for the application of ordinary people, or it was cumbersome and unclear and fast", in addition, the first draft also had problems such as insufficient ideology and lack of science, and decided to postpone the publication and revise it. Who knows, this change will be more than two years. Solicit the opinions of experts and readers, revise; and then solicit opinions and revise again. Even Ye Shengtao himself took the stroke of his pen, using the hands and eyes of his publisher, writer, and textbook writing expert to carefully deliberate on the first and revised manuscripts of the dictionary word by word, "in some places, they are revised like changing compositions."

In fact, we do not have to regret the many scholars of the Xinhua Dictionary led by Wei Jiangong, who have made great contributions to the final publication of the Xinhua Dictionary. It is just that the difficulty and time of compiling this new dictionary were initially underestimated, so that it was postponed again and again. Writing such a popular dictionary is not an easy task for scholars, because in addition to paying attention to science and accuracy, it is also necessary to pay attention to system, balance and conciseness. You know, the compilation of dictionaries itself is a specialized science, which requires a process of exploration. Even Ye Shengtao, who later personally participated in the revision, deeply experienced the taste, "The compilation of things is indeed extremely difficult, every time he changes it, he thinks that there is no disease, and he looks at it again day by day, and he sees the flaws, and he wants to seek refinement, how easy it is to talk about it." By the end of the compilation of the Xinhua Dictionary, the famous Chinese linguist Lü Shuxiang saw the sample of the dictionary and still thought that there were many problems. Ye Shengtao relayed this opinion to the editor-in-chief Wei Jiangong. I think these two strong advocates of the new dictionary may only have a relatively bitter smile at this time. In recent years, in addition to the heavy business and administrative work, they have spent a lot of energy on this dictionary, but the results are still unsatisfactory. Mr. Wei Jiangong is more familiar, he said: "Xinhua Dictionary" is a completely innovative dictionary, after several years of hard work finally got rid of the old dictionary, "it is better to copy other dictionaries" "good is a good thing." "If we want to be pure and correct, we can only wait for the opportunity to further revise it in the future." Ye Shengtao had no choice but to acquiesce to this result. They were all tired.

Three

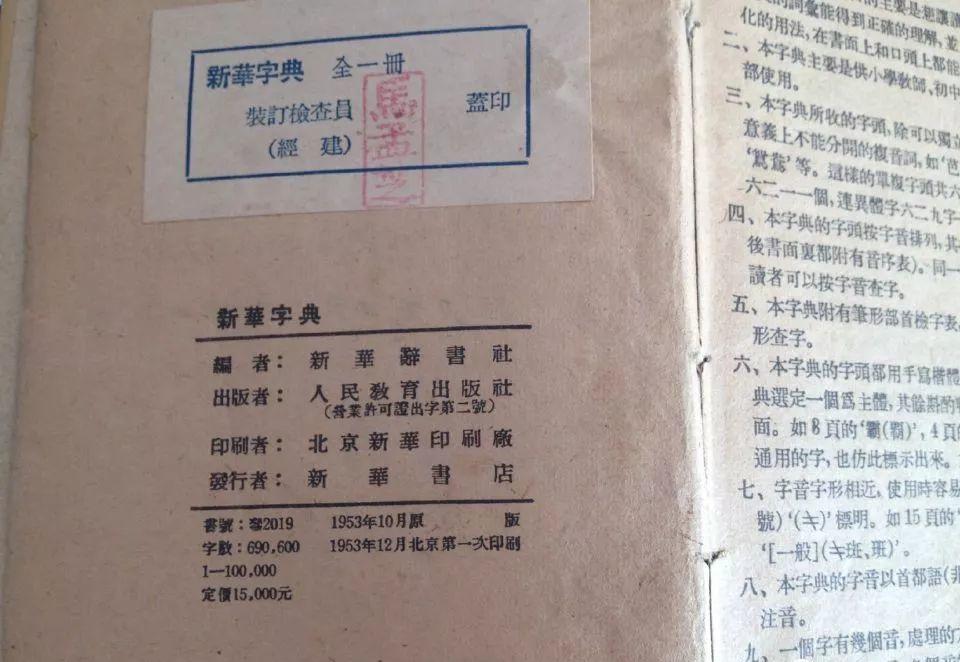

In December 1953, the first edition of the Xinhua Dictionary was published by the People's Education Publishing House and printed for the first time in Beijing. The title of the book was signed by Wei Jiangong. The copyright page said that 100,000 copies were printed for the first time, but Ye Shengtao's diary wrote 5 million copies, which sold out within half a year. In 1957, the Xinhua Dictionary began to be transferred to the Commercial Press for publication. Over the past 50 years, it has been revised 12 times, reprinted nearly 200 times, and its cumulative circulation has reached 400 million, creating many of the largest in the history of book publishing and distribution in China and even the world.

Today, it seems that after decades of polishing and the painstaking efforts of nearly 100 scholars, the Xinhua Dictionary has been called a fine dictionary. But all this is based on the first edition that the editors themselves were not very satisfied with. In fact, since then, the Xinhua Dictionary has drawn a clear line between it and any previous Chinese dictionary, becoming the first dictionary to use complete vernacular interpretation and vernacular examples. For example, the words "knife" cited above are illustrated in the first edition of the Xinhua Dictionary: 1. Tools used to cut, cut, chop, and cut: a kitchen knife, blade, single knife, and knife; 2. The unit of paper (the number is variable). Clear as words, practical and concise, and the so-called "National Pronunciation Dictionary" published five years ago (1948), there is a world of difference in style and content.

It should be said that the first edition of the Xinhua Dictionary is a striking coordinate in the long history of the Chinese language. More than 40 years after the implementation of the "Chinese Movement", the use of Beijing pronunciation as the common national language and the vernacular as the written expression of the text, these achievements that have been deeply rooted in the hearts of the people have been confirmed for the first time in the form of dictionaries and widely disseminated with a stronger influence. And it seems to be worthy of its name - "Xinhua", which exudes the atmosphere of the new era throughout. Because the compilers pay special attention to "wide collection of living language" and "suitable for the public", this dictionary truly reflects the vivid state of the folk Chinese language, which can allow the general public to carry it to the streets, alleys and fields, which is practical and kind. In the past few decades, when basic national education was not universalized and the number of illiterate and semi-illiterate people was huge, a Xinhua Dictionary was nothing more than a "school" without walls. It has made great contributions to the improvement of the overall cultural quality of this nation.

The Xinhua Dictionary is still being revised, reprinted and distributed, and it will always be with every reader in our country, because it is always new with the times. At the same time, we should not forget Wei Jiangong, Ye Shengtao, and a number of other great founders, who carried the legacy of the "May Fourth Spirit," cherished the lofty ideal of language innovation, and were full of enthusiasm for serving the cause of culture and education in New China, leaving this small book for generations of Chinese people, and even more a moving and long memory.

(Wu Haitao, text)