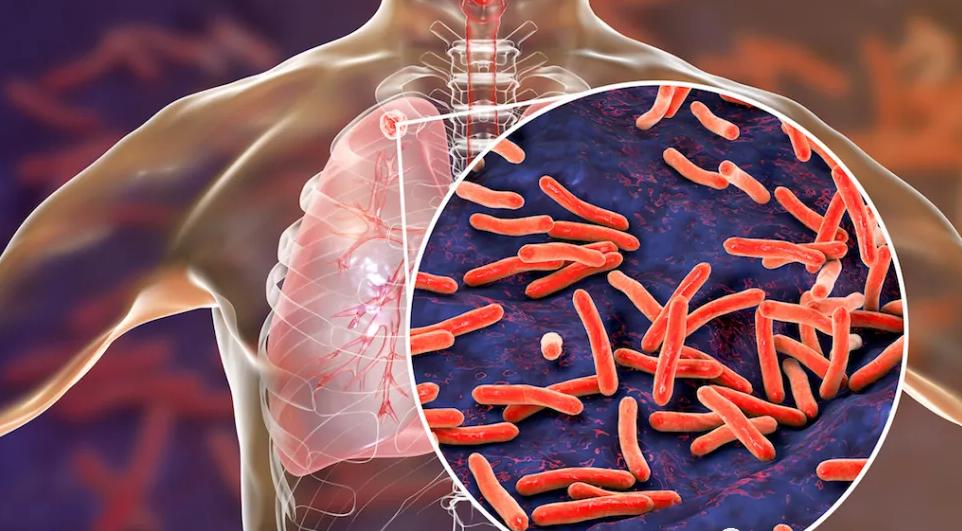

Tuberculosis is a very old and widespread infectious disease. It is a chronic infectious disease caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis, commonly known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Tuberculosis bacteria can invade various organs throughout the body, but tuberculosis is the most common.

Before 1882, tuberculosis had set off wave after wave of pandemics around the world. At the time in China, tuberculosis was known as tuberculosis; in Europe, it was known as the "white plague", and almost 100% of Europeans were infected and caused 25% of European deaths.

On March 24, 1882, german microbiologist Robert Koch (see photo below) declared that Tuberculosis bacteria are the pathogens of tuberculosis, thus opening up the mystery that causes tuberculosis and providing a cure for tuberculosis that has plagued mankind for thousands of years.

Although later with the continuous development of anti-tuberculosis drugs and the improvement of sanitary conditions, the incidence and mortality of tuberculosis have dropped significantly. However, the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria still contributes to the infection of about one-third of the world's population. According to the Global Tb Report 2021 released by the World Health Organization, there will be about 9.9 million new TB cases worldwide in 2020. In 2020, the number of new cases of tuberculosis in China was about 842 000, and the number of deaths due to tuberculosis was about 32,000.

In 1993, the World Health Organization declared tuberculosis a public health emergency. In 1995, the WHO designated 24 March as World TB Day to raise awareness and awareness of TB.

However, the origin of The mycobacterium tuberculosis remains a mystery to this day. Previous studies have suggested that the ancestors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis evolved from about 35,000 years ago. But the first (batch) human (patient zero) to be infected with TB is still being explored. There is a large number of views that deadly diseases, including tuberculosis, whooping cough and smallpox, were first spread by Europeans to the rest of the world during the colonial period. But recent new evidence suggests that TB in South America does not originate in Europe.

In a new study published in Nature Communicaitons, an international team of researchers led by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany and Arizona State University in the United States suggested that claims about the initial spread of TB bacteria may not be accurate. They found that centuries before tb first infected Europeans, a mycobacterium tuberculosis had spread from the coast of South America to the mountains inland. This suggests that there are other modes of TB transmission in these populations, such as human-to-human transmission, or the transmission of pathogens from terrestrial animals to humans through intermediate hosts.

In 2014, the research team isolated the intact Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) from remains of a thousand-year-old human archaeological skeleton on the southern coast of Peru. This predates the landings of Spanish, French and Portuguese colonists in South America. This archaeological evidence suggests that TB had spread among indigenous peoples before the arrival of Europeans.

In addition to the mycobacterium tuberculosis found in Peru, the researchers also isolated MTBC in human bones far from the coast in the Andes region of Colombia. This means that even in these vast mountains, TB appears to have been prevalent among indigenous local populations for a long time. As a result, tuberculosis had become a local epidemic at the time.

Subsequent genomic analysis found that these South American strains were different from those transmitted in modern humans, but were genetically most similar to the Pinnipede mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. pinnipedii), a strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis found in finned marine mammals such as seals and sea lions. Moreover, the most recent common ancestor of all gene-associated strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis appeared less than 6,000 years ago. This suggests that marine mammals may have been the first voyagers to carry TB bacteria and cross the ocean to South America.

Archaeological evidence from Peru and Colombia suggests that indigenous local people generally do not eat seal or sea lion meat traded from the coast. This means that the disease, which originated in pinnipeds, may spread inland far from the coast through another host.

It is well known that tuberculosis can be easily transmitted from one mammal to another. The researchers believe that these strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis may gradually dive inland over time, spreading between humans or between other terrestrial mammals, rather than directly from pinnipeds to humans.

In Today's New Zealand, for example, there are reports of tuberculosis spreading from seals to human-reared cattle, providing a bridge between sea life and land life.

Therefore, the study shows that european colonists infected with TUBERCULO bacteria landed in South America, which replaced the locally circulating strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, thus masking the deep ecological causes of the pathogenic bacteria's infection pathway.

Currently, the team is combing through the complex history of TB before the colonial era. Through genomic studies, they hope to identify new ancient strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to elucidate how the infectious disease is endemic at different times and in different locations.

The researchers concluded: "We believe that mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. a. 2000). Pinnipedii) is currently the simplest explanation for the spread of TB to inland areas. More genomic data from the Americas before the colonial era will help dig these clues further. ”

bibliography:

1.Geographically dispersed zoonotic tuberculosis in pre-contact South American human populations

2.Ancient Origin and Gene Mosaicism of the Progenitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0010005

3.Robert Koch: centenary of the discovery of the tubercle bacillus, 1882.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.37.4.246