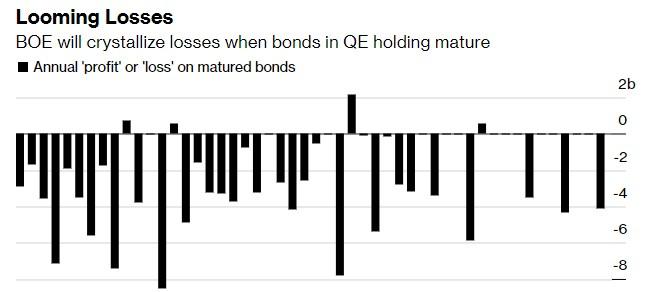

The end of the Bank of England's quantitative easing (QE) program will include a loss of £3 billion ($4.1 billion) in the coming weeks as interest rates rise and Treasury bonds held by the Bank of England will be lower than the issue price.

The Bank of England decided this month to start reducing its treasury reserves by £875 billion, which means that by the end of 2025, the Bank of England's holdings of UK Treasuries will be reduced by more than £200 billion. The problem is that most of these securities are paid much more than the par value, and once these securities are due or sold, the Bank of England runs a deficit, and the UK government must make up the difference; Based on the size of the bonds held across QE, the total difference is around £115 billion.

The end of quantitative easing has been a major moment for policy over the past decade as part of the Bank of England's aggressive monetary tightening. The Bank of England has raised interest rates twice and is expected to raise rates again before 2022.

Quantitative tightening (QT) is expected to begin in March, when £28 billion of UK government bonds will mature and will be withdrawn from the balance sheet for the first time since the introduction of quantitative easing in 2009; That would turn the £3 billion loss into reality, the difference between the nominal price of the bond and the price paid by the Bank of England. While the proceeds generated by the current remaining bond holdings are sufficient to cover this gap, rising interest rates will have a negative impact.

According to media calculations, by 2025 at the latest, the UK Treasury will start transferring cash directly to the Bank of England. And if interest rates evolve as the market expects, the low financing costs that quantitative easing has brought to the UK treasury will soon disappear. The higher the interest rate, the greater the damage to the government.

In 12 months, the cost of a 1 percentage point increase in the UK's public sector composite debt rate would be equivalent to 0.5% of GDP. Second, unlike the Group of Seven (G7), which has a median maturity of more than 14 years of outstanding treasuries, the median maturity of public sector consolidated debt is only 2 years, meaning that any period of long-term interest rate increases is dangerous. And, according to the OFFICE FOR BUDGET RESPONSIBILITy, this new situation – combined with the fact that about a quarter of the UK government's debt is now protected by rising inflation – also means that soaring inflation no longer has the same positive impact on debt ratios as it did decades ago.

Jagjit Chadha, director of the UK's National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said this week: "The treatment of quantitative easing is a huge problem. Quantitative easing has already brought more than £100 billion in returns to the UK Treasury, but this flow of money will reverse as interest rates begin to rise back to 1% or more. ”

Chadha warned that transferring taxpayer funds to the Bank of England could pose a new risk to the BoE's independence, which has received increasing attention during the pandemic.

The Bank of England and the Uk House of Finance communicated on the issue last week, with Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey highlighting an agreement that "reverse payments from the government may be required in the future and paid by the government in a timely manner". In response, Britain's finances reached Rishi Sunak's pledge that "any possible cash shortages in the future will be fully addressed".

In the 13 years since the Bank of England implemented quantitative easing, the UK Treasury has received £120 billion, mainly due to the net interest margin of the UK Treasury policy operation returned to the UK government through the Bank of England, offsetting some of the costs. This effectively means that the Bank of England would otherwise need to pay out to the private sector. However, as the gilts mature, the loss of capital in the portfolio held by the Bank of England will have to be compensated. Once interest rates hit 1%, the Bank of England will consider aggressively selling gilts, which could exacerbate the impact.

Quantitative easing schemes have recorded losses on bonds of around £28 billion, which were maturing in 2013 but have gone largely unnoticed because money has been reinvested and costs have been swallowed up by the aforementioned interest repatriation.

By 2025, however, if interest rates meet expectations, the UK Treasury will have to announce an annual budget shift to the Bank of England, a payment that is likely to become more common as the QE program is canceled. If interest rates had risen faster or higher, payments from the UK Treasury could have come earlier.