Recently, my book "Dunhuang Treasures of the Thousand Years of Dust" was published by Gansu Education Publishing House. This is a "small book" that aims to popularize the overview, content and value of the "Dunhuang Testament" to readers. However, although the volume is small, it has also been studied for many years. From the perspective of popularizing traditional culture, there seems to be a reason for saying it. So I was invited to write an article and write a little about my own experience.

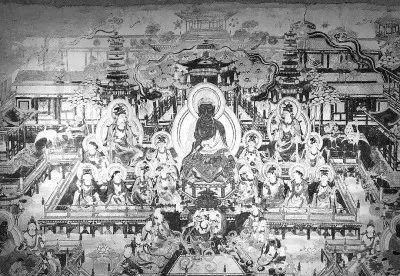

Dunhuang murals Picture from "Dunhuang Treasures of the Dusty Millennium"

"Dunhuang Treasure of the Thousand Years of Dust" Hao Chunwen author Gansu Education Publishing House Picture from "Dunhuang Treasure of the Thousand Years of Dust"

Russian-Tibetan unexplored scroll-bound Dunhuang testament Picture from "Dunhuang Treasure of the Dusty Millennium"

"Jingyun Second Year (711 AD) Grant shazhou thorn Shi Nengchang ren pardon" Picture from "Dunhuang Treasure of the Dust Millennium"

Crescent Spring Wang Mei Photo From "Dunhuang Treasure of the Dusty Millennium"

Dunhuang Testament, not a true "Suicide Note"

The "Dunhuang Treasure" in the title refers to the Dunhuang Testament. This suicide note does not refer to the letters left by the deceased before their deaths, but to the scriptures and documents left by the ancient ancestors of Dunhuang.

On June 22, 1900 (the 26th day of the fifth lunar month), the Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu stumbled upon a compound cave (now numbered Cave 17) on the north wall of Yongdao Road, Cave 16 of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes, which was stacked with scriptures and documents from the Sixteen Kingdoms to the Northern Song Dynasty. This batch of ancient documents with a total of more than 70,000 pieces has been called "Dunhuang Testament" by posterity.

Because the Mogao Caves were carved into the cliffs of Mingsha Mountain, the cave where the Dunhuang Testament was preserved is also known as the Dunhuang Stone Chamber or Stone Chamber. Because the main body of the Dunhuang testament is a handwritten Buddhist scripture, early people called the Dunhuang testament "Stone Chamber Scripture", and the cave where the Dunhuang testament was preserved was called the "Tibetan Scripture Cave". In addition, the Dunhuang Testament is also known as "Dunhuang Literature", "Dunhuang Manuscript", "Dunhuang Documents", "Dunhuang Scrolls" and so on.

"Dust for a thousand years" is an expression with literary overtones, and the nature, time and reason of the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave are indeed unsolved mysteries of the academic community, which inevitably makes people have various imaginations. Since no relevant records of the parties or descendants have been found, various theories about the nature, time and reason for the closure of the Dunhuang Scripture Cave are still speculations or hypotheses. At present, the Dunhuang testament excavated from the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave is written in 1002 AD (the fifth year of Song Xianping), so it is speculated that the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave was closed in the early 11th century. From the beginning of the 11th century to 1900, the Dunhuang Testament was buried in the Tibetan Scripture Cave for more than 900 years, close to 1,000 years.

In 1900, the mainland was at the end of the Qing Dynasty. The Western powers openly sent the Eight-Power Alliance to invade the mainland, and the national crisis of the Chinese nation's subjugation and extinction became increasingly serious, and the supreme ruler of the Qing court, who was busy running for his life, could not learn the news of the discovery of the Tibetan scripture cave in the northwestern frontier. In addition, most of the local officials in Gansu and Dunhuang at that time were dimwitted and ignorant, so that this treasure was not properly protected, and it was plundered by the "expedition" teams of Britain, France, Japan, Russia and other countries, resulting in the spread of Dunhuang suicide notes all over the world.

At present, the total number of more than 70,000 Dunhuang suicide notes is scattered in more than 80 museums, libraries, cultural institutions and some private hands in nine countries in Europe, Asia and the Americas. Among them, the National Library of China (with no. 16578), the British National Library (with a collection of about 17,000), the French National Library (with a collection of about 7,000) and the Institute of Oriental Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences (with a collection of about 17,700) are the four main collectors. The dispersal of the Dunhuang Testament is a major loss to the modern academic culture of the mainland, and has become a sad history of modern scholarship on the mainland, which is still difficult to let go!

"Writing the Scriptures in the Stone Chamber" encompasses the literature of all ethnic groups

Most of the text forms of the Dunhuang Testament are handwritten texts, but there are also a small number of engraved and printed texts and expanded copies.

In ancient times, before the invention and popularity of printing, documents and classics existed in the form of written books for a long time. During the Warring States and qin and Han dynasties, it was mainly written on bamboo and wooden janes. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, books copied on paper appeared, and by the Jin Dynasty, paper books completely replaced bamboo and wood simple books and shu shu. After the Song Dynasty, printing became popular, and printed texts gradually became the main carrier of books and knowledge dissemination, replacing the status of handwritten texts. Therefore, as far as the method and carrier of writing dissemination are concerned, roughly from the Jin Dynasty to the Song Dynasty, it was the era when handwritten paper texts were the main body, and after the Song Dynasty to the present, the era of printed texts as the main body.

The Dunhuang Testament was in an era when handwritten texts on paper were popular, so most of them were handwritten texts. After the Song Dynasty, the main carrier of the dissemination of books and knowledge was printed, but the engraving printing popular in the Song Dynasty was invented at least in the Tang Dynasty. Unfortunately, most of the early engraving prints have not been preserved. Fortunately, dozens of engraved prints have been preserved in the Dunhuang Testament, becoming part of the world's earliest surviving prints. One of the most famous, the Diamond Sutra of the Ninth Year of Tang Xiantong (868 AD), is the world's earliest surviving engraving with age, and is now in the collection of the National Library of The United Kingdom.

The stele technique appeared earlier, but the earlier takumi have not been preserved. Several of the Tang stele extensions preserved in the Dunhuang Testament have become the earliest known heirlooms in the world. These include the tuoso of Tang Taizong's "Hot Spring Inscription", Li Yong's "Huadu Temple Yong Zen Master Ta Ming", and Liu Gongquan's "Diamond Sutra".

The binding forms of Dunhuang testaments are diverse, including almost all kinds of binding forms of ancient books, but the vast majority of them are scrolls. Scroll loading, also known as roll loading, is a form of binding that has been popular for a long time and has a wide popularity area after the emergence of paper books and documents. The method is to first glue the paper into a long roll as needed, and then use a round wooden stick to glue it to one end of the paper, spread it flat when reading, and roll it into a scroll after reading, which is the book or document contained in the scroll. In addition to the reel load, there is also the Brahma clamp. The Van Clamp came from India. Because the scriptures are Sanskrit, there are two splints on the top and bottom, so they are called "Brahma clips". The "Fan Clamp" in the Dunhuang Testament is a fan clamp that is imitated or changed. The first change is that the text is no longer written on bayes, but on paper; the second change is that the text is mostly written in Chinese. In addition, the Dunhuang Testament also preserves the binding styles such as "folded", "whirlwind", "butterfly", "bag back" and "line".

The text of the Dunhuang Testament is mainly in Chinese, but it also preserves many Hu literature used by the ancient Hu people.

Among such documents, Tubo is the most common. Tubo, also known as ancient Tibetan, is a script used by the Tubo people during the Five Dynasties of the Tang Dynasty. Because the Tubo people had ruled Dunhuang from 786 to 848 AD, during which time they had implemented the Tubo system and the Tubo language and script in Dunhuang, a large number of Tubo documents were also preserved in the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave, about 8,000 pieces. This batch of documents is of great value for the study of the history of Tubo and Dunhuang, as well as the ethnic changes in the northwest region at that time.

The second Hu literature in the Dunhuang Testament is the Uighur script. The Uighur script is a script used by the ancient Uighurs, also known as the Uighur script. During the Tang and Song dynasties, the Uighurs played an important role in the history of Dunhuang. Since the late Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang's eastern and western prefectures of Ganzhou and Suzhou and western Dunhuang have all had Uighur regimes, and there have also been Uighur residents in the Dunhuang area. For the above reasons, more than 50 Uighur documents have also been preserved in the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave. The contents of these documents, including letters, accounts, and Buddhist documents, were of great value for the study of Uighur history and culture.

In addition, a small number of Khotanese, Sogdian and Sanskrit scripts are preserved in the Dunhuang Testament, all of which are of great value for the study of ancient ethnic relations and Sino-foreign exchanges.

The earliest known Dunhuang testament is the Wei Ma Jie Jing written by Xiang Gao, the King of Later Liang, in 393 AD (the fifth year of Hou Liang Lin Jia), and this document is now in the collection of the Shanghai Museum. The latest date is the above-mentioned inscription of Cao Zongshou, the king of Dunhuang in 1002 (the fifth year of Song Xianping), which is in the collection of the Institute of Oriental Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. From 393 AD to 1002 AD, the time spans more than 600 years, and most of the Dunhuang testaments were written or copied in the late Tang Dynasty and the early Song Dynasty.

Study of the suicide note and rewrite the history of the Middle Ages

In terms of content, the Dunhuang Testament can be said to be all-encompassing, but because it is a Collection of Buddhist Monasteries, the largest collection is Buddhist classics, accounting for about 90%.

Many of the Dunhuang Buddhist texts are handed down Buddhist scriptures included in the Great Tibetan Sutras of the past, such as the Great Prajnaparamita Sutra, the Vajrapani Prajnaparamita Sutra, the Myo-Dharma Lotus Sutra, the Golden Light Most Victorious King Sutra, the Vimalaya Sutra, and the Mahayana Sutra of Immeasurable Life. Although the above scriptures exist in the heirlooms, due to the early age of the Dunhuang Testament, they still have important collation value and cultural relics value.

The Dunhuang Testament also preserves many Buddhist texts that are not found in the Great Tibetan Scriptures. These "Yijing" and buddhist texts that are not in Tibet have higher documentary value and research value. Among them, the most important is the preservation of a number of ancient scriptures, such as the Diamond Sutra, the Lotus Sutra and the Vimalaya Sutra, which have more than 130 kinds and more than 530 pieces. These sutras are the understanding of Buddhism by Chinese Buddhists, so they can truly and concretely reflect the characteristics of ancient Chinese Buddhism.

In addition to Buddhist texts, there are also Taoist texts, Jingjiao (Christ) texts, and Manichaean texts. The most striking of the Taoist texts is the rediscovery of the Commentary on the Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu, which, although fragmentary, preserves the verses and commentaries from chapters 3 to 37 of the book, providing new materials for the study of Taoist history and revealing another way of enlightenment of Taoism. Jingjiao literature such as the Zun Jingjing, the Great Qin Jingjiao Sanwei Mengduzan, the Great Qin Jingjiao Xuanyuan Benjing, and the Manichaean literature such as the Mani Guang Buddhist Ritual Strategy, the Lower Part of the Zan, and the Sutra of Proving Past Cause and Effect provide important materials for the study of the circulation of ancient Jingjiao and Manichaeism.

Although the total number of documents other than religious documents is not large, accounting for only about 10%, the content is very rich, involving ancient history geography, society, ethnicity, language, literature, art, music, dance, astronomy, calendar, mathematics, medicine, sports, ancient books and many other aspects, many of which are not found in the first-hand information of the canonical history.

In terms of history, the Dunhuang Testament preserves public documents such as book making, edict, and confession, legal documents such as laws, orders, rules, and styles, enlistment documents such as household registration and poor subject books, and contract documents such as sale, loan, employment, and leasing. These materials are of great value for understanding the political and economic situation in ancient China. For example, "Tang Jingyun Second Year (711 AD) Zhi shazhou Thorn Shi Nengchang Ren Edict", is the original tang Dynasty "On the Matter Of the Edict", 8 lines of text, the document has the "Seal of Zhongshu Province", the middle of the big "edict" is particularly eye-catching, this document has become a landmark symbol of Dunhuang documents. Based on this document, with reference to other literature, we can roughly understand the complex process of the "Edict of Facts" from drafting to issuing. Another example is the "Tang Kaiyuan Water Ministry Style", which stipulates in detail the Tang Dynasty's management system for canals and bridges and the relevant responsibilities of governments at all levels, which not only provides valuable information for understanding the water conservancy management system of the Tang Dynasty, but also corrects the errors recorded in the "Six Classics of Tang", "New Book of Tang" and "Old Book of Tang". At the same time, it also enables us to have a specific understanding of the content and form of the Tang "style", and provides a textual model for collecting other Tang-style articles from The Tang Dynasty literature.

The social history materials preserved in the Dunhuang Testament mainly include "clan genealogy", "calligraphy", "Sheyi documents" and "monastic documents". The "clan genealogy" is the information that records the surnames of the ancient families; the calligraphy is the program and model of the ancient people's letters, including many regulations on the etiquette and customs of the time; the "Sheyi Documents" are the specific materials of the ancient folk associations; the "Monastic Documents" record the life of the Dunhuang monks in the fifth dynasty of the Tang Dynasty and the early Song Dynasty and their connection with society. These materials concretely reflect the real situation of life in ancient times. For example, with regard to the lives of ancient monasteries and monks, according to the Buddhist scriptures and relevant records, ancient monasteries should be a basic living unit, and monks and nuns lived a collective life in which all the monks and nuns lived in the monasteries and were fed by the monasteries. But the Dunhuang monastic documents show us another picture of the life of monasteries and monks and nuns. First, some monks and nuns do not live in the temple, but in lay families outside the temple. Second, the monks and nuns who live in the temple also live an individual life of eating and living alone.

The literary works preserved in the Dunhuang Testament are the most eye-catching among the popular literary materials, including scriptures, causes and conditions, variations, scripts, words, stories, poems, etc. The study of these popular literary works can be said to have largely rewritten the literary history of ancient China. For example, the study of literary materials such as Dunhuang variations and scriptures has solved the problem of the source of popular folk rap literature such as drum words, palace tones, words and phrases, and treasure scrolls.

In summary, whether from the perspective of quantity, time span or cultural connotation, the discovery of the Dunhuang Testament can be said to be the most important cultural discovery in the mainland in the 20th century. Even worldwide, it is a unique cultural treasure. I look forward to more scholars joining the research ranks of this treasure.

Source | Guangming Network