【New Books in Academia】

■ Wu Jiang (Former Executive Vice President of Tongji University, Academician of the French Academy of Architectural Sciences, Professor, PhD Supervisor)

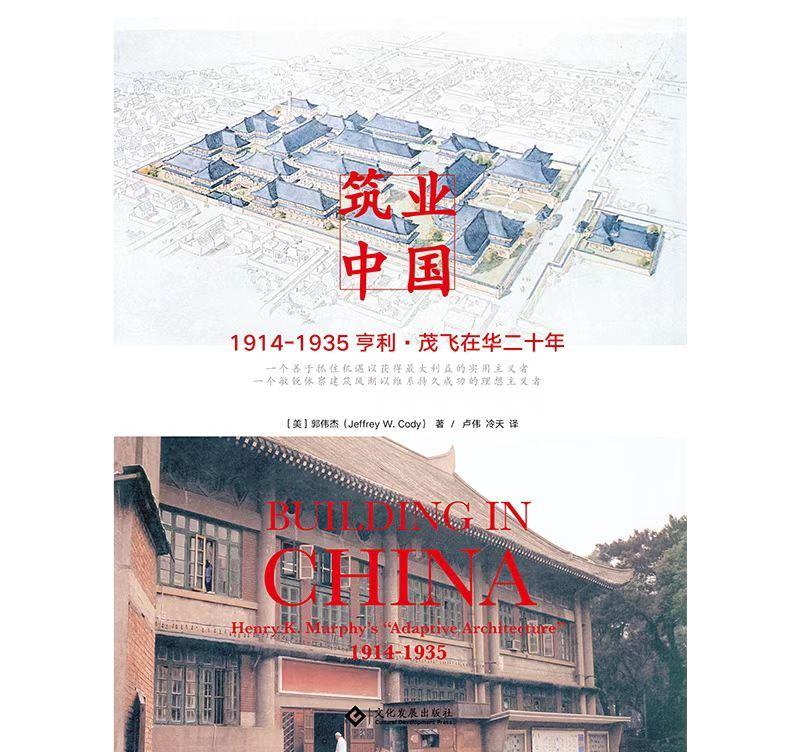

20 years after the Publication of the English edition of Dr. Guo Weijie's "Zhuye China: Twenty Years of Henry Maofei in China from 1914 to 1935" (hereinafter referred to as "Zhuye China"), the Chinese edition was officially published. As a scholar of architectural history, I have always believed that the value of a truly valuable research result must be permanent, not temporary. This work is an excellent example. Even if the Chinese edition has just been seen now, it still shows the frontiers of its research and the persistence of its results. The book is the author's doctoral dissertation at Cornell University. I was one of the first readers of this doctoral dissertation. After the completion of the paper, it took almost 10 years of continuous deliberation before it was officially published in 2001, which is enough to see the academic rigor of the author. In the 20 years since its publication, the English edition has long become an important and irreplaceable achievement in the study of modern Chinese architectural history. Dr. Guo Weijie has also become a world-renowned important scholar of modern Chinese architectural history. The publication of this Chinese edition will give more Chinese readers the opportunity to read directly, and I believe it will still have a broader impact on the Chinese academic circles in modern Chinese architectural history and even other related fields.

As the author says in the book, Mao Fei has a special influence on modern Chinese architecture, but has received insufficient attention in the study of architectural history. His influence is not only expressed in a series of important works, but also in his promotion of modern translation of traditional architectural forms in modern Chinese architecture. Needless to say, at the intersection of the previous century, architects from the West were the first to face up to and try to answer the historical question of how Chinese architecture can face the strong impact of modernization and realize the adaptive transformation of traditional architectural forms. Mao Fei is one of the most active Western architects. His architectural design ideas directly influenced a large number of Chinese first-generation architects represented by Lü Yanzhi. Although the traditional revival movement that was actively promoted by the Chinese architectural community after that had a broader and more complex background and motivation, it must not be said to be unrelated to the extensive exploratory practices of early Western architects in China such as Mao Fei. In this regard, this book gives very convincing circumstantial evidence. The revival of tradition in the history of modern Chinese architecture is a subject worthy of in-depth exploration, tradition and modernity, in the process of chinese architectural modernization, have always been intertwined, and have never been a simple dualistic relationship - neither the old and the new, nor the east and the west. This book opens up a broad path for research in this field.

Guo Weijie and I have known each other for more than a third of a century. In the summer of 1987, he came to Tongji University to conduct a one-year doctoral dissertation research under the guidance of Professor Luo Xiaowei, and as a graduate student of Mr. Luo, I had just graduated and stayed on to teach for a year, plus I was already conducting research on modern architecture in Shanghai (a year later I officially re-entered Mr. Luo's doctoral student), and we naturally became the closest classmates and partners. He was actually 10 years older than me, and I really saw him as a senior in learning and a brother in life. I helped him practice Chinese, and he helped me learn English (I later learned that he had a very deep knowledge of English language and literature). Due to the similarity and relevance of the research field, under the guidance of Mr. Luo, Guo Weijie and I inspected modern architecture together, participated in national academic seminars, and left our footprints in Nanjing, Changsha and Wuhan. In Nanjing, we rode our bicycles to brave the snowstorm to investigate, and sat by the fire in my parents' old house in Nanjing to bake wet cotton shoes together, and the scenery is still vividly remembered. I also consciously learned from him the research methods and working attitudes he brought from the United States. We spent a year together, but it affected our whole lives. He later went to Work in Hong Kong and became one of the founders of the Department of Architecture at the University of Chinese, Hong Kong. I visited the University of Hong Kong as a visiting scholar from 1993 to 1994 and had another chance to meet them. At that time Chinese University had just opened the Department of Architecture, and he had a very good reputation among his colleagues and classmates. All of his colleagues became good friends of mine. He had great respect for Mr. Lee Chan Fai, the head of the department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and never stood tall because he was An American (at that time, colonial-ruled Hong Kong was still a foreigner). He really achieved "taking the department as home", in addition to teaching his every class, he had to go to the design classroom every night to inspect the lights, doors and windows, and the last to leave. He helped Chinese University create the Architecture Library and led me to "show off" the fruits of his work. Today, the Department of Architecture of Chinese University in Hong Kong is a towering tree, and I think teachers and students will not forget the contribution of Professor Kwok Wai Kit. I admire him for his teaching work, which he often considers his papers and uses every opportunity to discover new material and interview people who know. By then, he had already graduated with a ph.D. and his dissertation had entered the Library of Congress. But he told me that he still hoped to have the opportunity to officially publish it, and as long as he had the opportunity to obtain new materials or have new ideas before the official publication, he would definitely revise it in time. A few years later, when he finally signed a publishing contract for the Hong Kong Chinese University Press, he told me for the first time that his joy could not help but be. At that time, he had already published his doctoral thesis "A Century of Architectural History in Shanghai" a few years earlier, so I could understand his mood at that time. When I first received his new book, still scented with ink, I was taken aback because it was a new book compared to the doctoral dissertation I saw 10 years ago. This also prompted me to decide to republish my "100 Years of Architectural History of Shanghai" on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the publication, and to re-present the old works of many years ago to the readers in a new way.

When the Chinese edition of "Zhuye China" was published, I nagged the above words, and my excitement overflowed into words. I am happy not only for the book, but also for the author, the senior and friend of my life, and even more happy that more Chinese readers have the opportunity to read this academic work directly in their native language. Thank you to the author, thank you to the translator, thank you to the publisher, thank you to all the people who made this book a reality. (This article is authorized to be excerpted from "Zhuye China: 1914-1935 Henry Maofei in China Twenty Years", slightly abridged, and the current title is added by the editor)

Source: China Youth Daily client