The original article @ Du Mang is published in the middle reading app

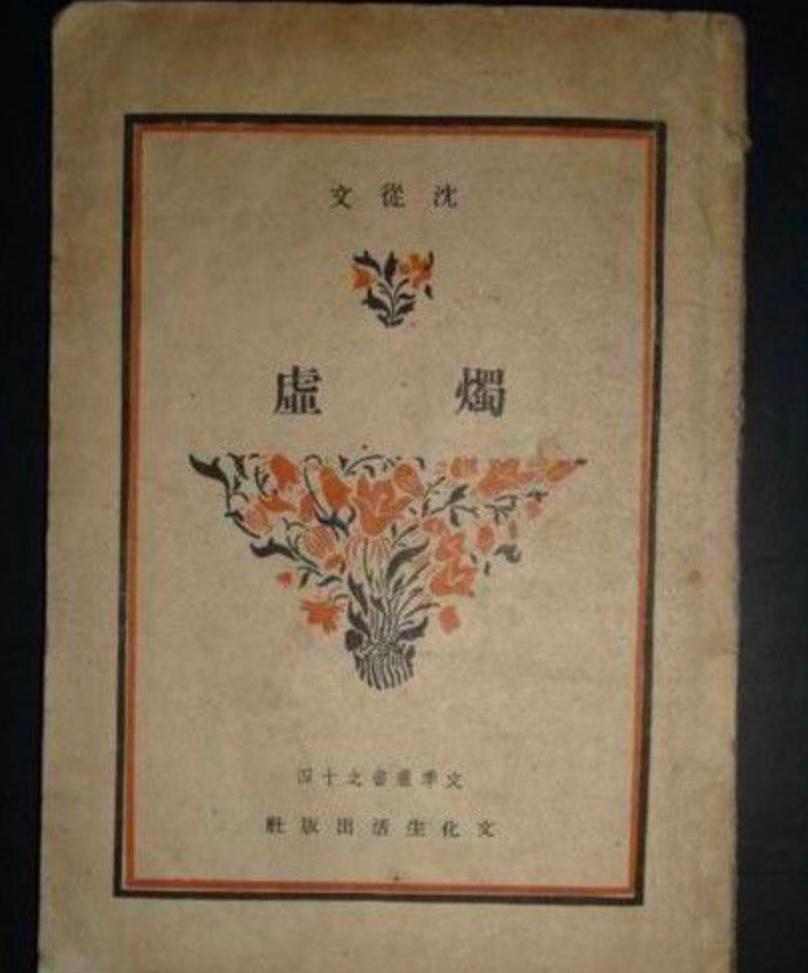

From 1939 to 1941, Shen Congwen successively published a group of prose works (< Candle Void >, < Qianyuan >, < Changgeng >, < Life >), which were later included in the first series of the prose collection Candle Void published in August 1941. A central thread that runs through these words is Shen Congwen's reflections on the meaning of life.

CandleLight

In the opening < candle > of this series of articles, the main text of the first and second parts is a discussion of modern women's education, but the inscription in front of the main text is full of lyrical beauty and philosophical profundity. Let us first look at the inscription of one of the > of the < Candle: "To discern the arrogance and ignorance of mankind is as great a cause as to contemplate the sufferings of the elderly, dead, and sick, and the positive can be regarded as a great work, and in the negative it is also an interesting pastime." In the above inscription, Shen Congwen clearly stated that we must reflect on the limitations of human beings in both spiritual and physical aspects. Comparatively speaking, human beings have always had a sober understanding of the fact that human physical life must pass through life, old age, illness and death, but most of them regard it as a helpless tragic fate, that is, thinking about the meaning of life and death only from the perspective of human individual existence. On the other hand, man's rationality and ability to himself are sometimes infinitely exaggerated, and eventually transformed into a worship of the self and cannot extricate himself. Not only does humanity lack self-examination, but since the beginning of modern times, this excessive self-confidence has become an important part of the zeitgeist with "progress" as the core and has been highly praised. From a contemporary ecologicalist perspective, both of these mentalities exhibit the narrow-mindedness and arrogance of anthropocentrism, which is both the root cause of many modern social problems and one of the culprits that lead to the alienation of man from nature and the imbalance of ecosystems.

In the < Candle Void > the following parts of the text and the other three essays in the same series, Shen Congwen's thinking on the lack of modern civilization quickly transcended the criticism of the specific shortcomings of urban civilization and turned to poetic language to explore the innate finiteness of individual life and the dialectical relationship between life and nature and the living world. In the inscription of the second > of the < Candle, Shen Congwen clearly pointed out the smallness of man in the face of nature:

Nature is both vast and cruel. Overcome everything and nurture all beings. The ant worm, the great man and the great master, are just as in its arms and the light and dust. Due to metabolism, there are Huawu Hills. The wise man understands that "phenomena" are not bound, so he can use words to make the light of life shine like a candle like gold when all life loses its meaning one after another and is meaningless because of death.

In the face of nature, man's existence is fragile, short-lived, and even insignificant; only by understanding and accepting the finiteness of his own existence and thus reconstructing his relationship with nature can he comprehend the deeper and broader connotation of existence in the face of the loss of meaning in individual life due to death. Here, nature is not the object of human domination and transformation, but a great being that operates according to its own logic and encompasses man and all life. However, this kind of nature is not a "noble" nature that is diametrically opposed to human beings and simply arouses human awe and fear, but a positive factor that closely blends with human beings and builds a living world together. At the beginning of the text of < Candle Void > Ii, Shen Congwen described such an ideal scene:

Last afternoon, I went to Chenggong to see the children, and when I got off the bus, it was nearly dusk, and I got on a skinny maroon horse and walked toward the southwest field. See the western sky, where the sun sets, the clouds are bright and yellow, and the mountains are green and blue. The eastern Changshan Mountains still reflect the afterglow of the setting sun, leaving a deep purple. The breeze in the bean field, the green waves turning silver, the radish flowers and rape flowers yellow and white, all the scenes are solemn and gorgeous, it is really touching. We are contemplating the meanings of time and space, life and nature, history or culture. It is like using a piece of light color as a medium catalyst, which has caused many strange feelings.

In this ordinary country walk, the natural scenery appears "solemn and gorgeous" in the eyes of the author, reflecting the greatness and order of life. At this moment, the author is in close harmony with nature, and crosses time and space, across the boundaries of nature and history and culture, forming a unified vision of the living world, and has a profound grasp of the whole of existence. Unfortunately, this harmonious scene was soon broken by the laughter and play of two modern schoolgirls passing by. These two schoolgirls, who represent modern urban civilization, show triviality, shallowness, and indifference to the deep connection between man and nature. Shen Congwen did not have a particular prejudice against women; he then enumerated various strange phenomena of modern civilization, pointing out that this shallowness and narrowness of the mind actually exist widely in all groups in modern society, especially among intellectuals who consider themselves to be progressive. Contrary to this numbness of modern civilization, Shen Congwen is sensitive and curious about the beauty of nature, the great mystery of life hidden behind this beauty, and the mysterious experience of man and nature. In the essays included in the first series of Candlelight, he uses poetic language to create various ideal scenes, vividly and tortuously conveying this unique life experience to the reader. Here are a few examples:

I need to be quiet, to be in an absolutely lonely environment to digest and digest the concreteness and abstraction of life. The best place to go is to sit on a large stone next to a small river in front of a temple, which has been bleached and polished by sunlight and rain. When the rainy season comes, there are some green velvet-like mosses on it, and once the rainy season has passed, the moss has dried up, and on a piece of undried moss is blooming small blue flowers and white flowers, and there are thin-footed spiders crawling next to it. The river water flows from between the stones, and the shells of the stone mussels in the water are clearly distinguished. A large tree grew next to the stone, its branches green and its leaves peeled off. I need to be in such a place, for a month or a day, when I have to be completely cut off from foreign objects, in order to be able to re-approach myself.

Another example:

Extremely tired after meals. Take a walk on the earthen embankment of Green Lake. The leaves are slightly peeled off, the safflowers are withered, and the water is clear and the grass is chaotic. Pig ear lotus is still blooming lilac flowers, still close to the water. The sun shines on the earth, and as the sun reaches, the eyes look up, but the house is a tree, and a pool of clear water, all of which are more related to each other. However, the individual's life is turned into a sense of loneliness, with no refuge and no attachment. Heaven and earth, sticky.

Live upstairs and smell the wolves in the mountains in the middle of the night. See a star in the window, the light is weak and beautiful, as if there is some hope. What my eyes and ears have received seems to have left me with a much clearer and deeper impression than some of the works of some who have been called great masters and masters.

Shen Congwen

In these scenes, what Shen Congwen strives to pursue is not only a small Greek temple of "humanity" in his ideal. On the other hand, he does not simply stand in the position of an objective observer to capture and describe the beauty of nature. When he broke through the isolated thinking of "human nature", he went on to pursue a broad sense of "life" in which man and nature, and everything in the living world, blended with each other. On the one hand, this life experience reveals the universal meaning of existence by breaking through the individual self and reaching the depths of existence; but at the same time, this mystical life experience is concrete, highly personal, and even a flash of inspiration, fleeting, "out of the shape, the handshake has been violated." It cannot even be adequately expressed in the limited language of human beings. Shen Congwen, who wrote the above-mentioned Shen Bo's beautiful words, still sighed: "What am I talking about? Everything that can be written is nothing but the dross of one's fantasies. But if we have to force language into words to express this life experience, then the only form we can take is figurative, metaphorical, poetic language, not abstract, analytical, scientific, and empirical language. This experience of life and its unique form of expression are inseparable from each other. This organic connection between content and form can be further corroborated by the following text:

Let me give you an example. It was as if at some time, somewhere, someone, the breeze was blowing, the mountain flowers were shining, the river was muddy and vibrant, and there were floating vegetable leaves. There are small frogs jumping among the grasses along the river, female cattle in the distance calling for children in the bean fields, and shipbuilders' axes in the upper or lower reaches of nowhere, far across the valley. There are purple flowers, red flowers, white flowers, blue flowers by the river, and each flower and each color contains a moving memory and beautiful association. Try to pick a bouquet of blue flowers, throw it into the river, let it flow away with the vegetable leaves, and then trace the history of this flower, then long hair, pink face, and plain feet are all displayed in the impression, as if strange, familiar. Originally dispersed, not adhered to each other, at this time the knots are suddenly spelled into a complete shape, the eyes are beautiful, the hands and feet move slightly, such as smelling the song, it seems to have love and resentment. After a while, everything has disappeared, and only a white dove flies in the void, in the void that does not occupy the eyes of others and other substances. A white light was shaky, silent, fragranceless, only white. Although the Lotus Sutra has a very beautiful description of this emotion, it still makes people feel that words are very bad, and it is difficult to capture this realm. After a while, the green trees in the open window have become obsolete, but there are still small red flowers in front of the window that are bright and dazzling in the impression, like burning. This heart is also burning like a fire... Alas, God. The fire of life burned and extinguished, a little blue flame, a pile of ash. Whoever sees, who understands, who believes.

The present experience, memory, imagination of "witnessing The Tao", all these interrelated perceptual experiences merge, reorganize, sublimate in the author's inner spiritual world, and ultimately point to the life experience and pure "beauty" that transcends language and figuration, is supreme and transcendent, is infinite, and contains all things. This is both an experience of the mystical nature of existence and an pictorial description of the process of artistic creation. The intrinsic similarity between the two determines that they are mutually superficial; only this intuitive, poetic language can undertake (though still only partially) the mission of revealing the mysteries of existence.

Shen Congwen often describes this supreme, but deeply hidden "beauty" in all things, and corresponding to this beauty, the vast life experience of turning to merge with the universality of the living world after recognizing the limitations of individual existence, Shen Congwen often describes it as "abstract" in this series of essays. What this "abstraction" means is not abstract thinking in rational analysis and judgment, but the overall grasp of "beauty" and life experience; at the same time, it is a mysterious realm of "verbal judgment". In the fifth > of the < Candle, Shen Congwen mentioned that it is necessary to "digest and digest the concreteness and abstraction of life in an absolutely lonely environment"; in the > of < life, he shouts: "I am going crazy." Crazy for abstraction. I saw some symbols, a piece of shape, a handful of lines, a kind of silent music, poetry without words. I see a most complete form of life, all of which exists well in the abstract and is destroyed before the facts. In Shen Congwen's mind, the meaning of "beauty" is not limited to a specific external form or individual aesthetic experience; in its ultimate sense, "beauty" is the highest value standard that transcends utilitarian calculations and secular morality, covers "truth" and "goodness", is a direct expression of the mysteries of existence, and is an ideal realm that is far away from narrow human nature and close to divinity. As he extolled:

In my lifetime, I discovered "beauty." That body and thread represent the highest virtue, which makes man happy to be ruled by it and disposed of by it. Human wisdom is influenced by this. Elegant words make them dull compared to the ornate literature, like the fine stars shining on the moon. It may be a collection of people, an object, an abstract symbol, and people just want to bow their heads to show piety. The Arabs touched the ground with their lips in the desert, indicating the Allah of conversion, and the mood was the same as in this situation, meaning that they had not approached God's Allah, but at least they had approached God's creation.

This "abstract" understanding of life and beauty is actually the ultimate pursuit of the "most complete form" of life and the beauty of "representing the highest virtue" in the process of getting rid of the barriers of urban civilization, breaking through the limitations of daily experience and individual life, striving to merge with all things and grasping the whole of the living world; in other words, this "abstraction" reflects the limited modern subject through the experience and reflection of concrete life, especially the ideal life in harmony with nature 2. Grasp the infinite attempts. The pursuit of "abstract" beauty became an important theme of Shen Congwen's creation in the 1940s, in addition to "Candle Void", in the < to see the honglu > (1940), the < water cloud > (1943), the < Green Nightmare > (1943-44), the < White Nightmare > (1944), the < Black Nightmare > (1944), the < Cyan Nightmare > (1946), the < Hongqiao > (1946) and a series of other works, Shen Congwendu sought to reflect his latest thinking on abstract beauty.

But crossing the gap between the finite and the infinite is a difficult task, and there is always a great tension between the two: "Because beauty is close to 'God', that is, far from 'man'. Life is divine, living in the human world, facing each other, and disputes follow. Emotions can fly high and soar, and the flesh is sluggish and heavy, not far from the earth. Therefore, what "exists well in the abstract" is "destroyed before the facts." Thus, the writer's quest for "abstraction" thrilled and fascinated him; he struggled to get to the other shore, but never reached it. This contradiction reflects the historical limitations that the modern subject is insurmountable in reality, and it is the same as the "shadow" of the sudden lyrical pastoral narrative discussed in chapter 3 of this book. Although Shen Congwen's attempt to grasp "abstract" life and beauty through nature has a clear relationship with the traditional chinese and Western concepts of nature, similar inner tension and even anxiety are difficult to find in the natural aesthetics under the traditional concept of heaven and man. When Shen Congwen strives to convey this "abstract" beauty and the realm of life through a figurative literary language in his works, and thus overcomes the contradiction between the above-mentioned limited subjects and infinite pursuits, a moving scene emerges in his pen, but at the same time full of complex allegory:

The stone road in front of the gate has a slope with rows of green trees, long dry and weak branches, and green leaves, such as cuiyi, such as feathers, like flags. There are often mountain spirits, showing waists and white teeth, coming and going. Those who meet it are dumbfounded. Love can make people dumb—a language that calls death. "Love and death as neighbors".

In the first part of this scene, the author first outlines a small hillside covered with green trees on the side of the cobblestone road before leaving the door. Although this is not a real description of the name, it is still a small scene of daily life that the reader is familiar with. Suddenly, however, an image beyond real experience appears in front of the reader's eyes: "a mountain spirit with white teeth and white teeth, coming and going" in between. This image immediately reminds us of the mountain ghost in Chu Ci's "Nine Songs": "If someone is a mountain man, he will be taken by Xue Li xi to take a female luo." It is both eye-catching and smiling, and Zi Muyu is good at it. It is an image that connects man and nature, reality and fantasy, and an image full of charm, connecting love and death. Her form is the perfect human woman (let's say female--- but not impossible for men), and her beauty is fascinating; but at the same time she is a god beyond reality, and although people are eager to pursue, they are always inaccessible.

The mountain ghost in The Nine Songs

In Shen Congwen's imagination, the mountain spirit travels back and forth in the mountain forest near the human world, and as she travels, the boundaries between the human world and the divine world, the present world and the other shore are gradually blurred, and finally merge into one, and it is difficult to distinguish between each other. When man meets this mysterious mountain spirit, "the one who meets is dumb": this loss of voice shows both the ecstasy of mankind at the moment of grasping the supreme, "abstract" beauty, and that this mysterious experience has transcended the limitations of human language. As far as the subjective experience of the experiencer is concerned, once this "abstract" beauty is captured, the ensuing ecstasy will so intensely and so thoroughly grasp the body and mind of the discoverer, causing him to be "poisoned, like electricity", "dumb and withered, unable to move, losing what he believes in". In this highly subjective and personal experience, the modern subject seems to have completely abandoned the control of the individual self and escaped into a realm similar to the "I lost myself" in Zhuangzi Qiwu. If we try to convey this feeling to the reader in words, then, in all the everyday experiences that we are familiar with, it seems that only death will bring a similar complete negation to the individual self, so Shen Congwen laments here: "Love and death are neighbors." But here death is not the end, but another beginning. Through the baptism of "beauty", man can be reborn from death and obtain new life --- a life that is deeply in harmony with nature, is connected with everything in the living world, and has insight into the true meaning of existence under the clear illumination of the supreme "beauty". But, on the other hand, this ideal of death and rebirth may never be perfectly realized, just as human beings will never be able to capture the mountain spirits that loomed at that time. Shen Congwen sighed in < Qianyuan > (II):

...... The heart is very upset, as if it has no autonomy for survival, but if you think of one thing, you can avoid being trapped in the mud. However, what is now leaning on itself is like an object drowning in the abyss of "unknowable". Although the entanglement of the algae sinks very slowly, it is clear that life is sinking. The abyss is bottomless and it is not easy to touch the feet. The deeper the sinking, the greater the pressure, so the auditors and the officials gradually lose their sense of acuity... Having seen much, it is merciful to realize that life is reassigned. Two thousand years ago, Zhuang Zhou used words to build a concept of "wisdom" and "liberation", precisely because life clings to "facts", generates compassion, and is strong as an interpretation to masturbate.

From this point of view, we will have a less optimistic interpretation of the image of death with the mountain spirit. In death, there is not necessarily the ecstasy of encountering "beauty" and the potential for rebirth. Death is death--- it is only the inevitable end that every living being cannot escape. For the individual, death is the ultimate negation of the meaning of his existence, a terrible nothingness with no future. Behind death, there is no salvation or deliverance that is comforting enough.

But between extreme ecstasy and extreme nothingness, in Shen Congwen's thought, we may also find a third possible interpretation of "death." Death as the end of individual existence, while at the same time returning us to the cyclical operation of nature and the living world. The enlightenment of living to death can help the human subject to explore the arrogance of delusion, form a deep understanding of the meaning and limitations of life, and at the same time highlight the characteristics of the living world that is always open to the unknown; and returning to nature through death is an important way to reconcile human beings and nature again, to make human beings jump out of their self-centeredness, and to understand the close connection with the living world. But this recognition of death does not promise an unmistakable ultimate salvation or liberation, nor does it predetermine the subject's necessary path beyond the limitations of his own existence; it merely provides a possibility, an intrinsic dynamic that constantly pushes us to discover or reconstruct the meaning of life by thinking about death.

"Weeds"

In early modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun's "Weeds" pioneered the exploration of the relationship between "death" and modern subjects, but after that it was followed by no one for a long time. In my opinion, among the modern Chinese writers, Shen Congwen is the writer with the most profound and unique experience of "death" after Lu Xun, and what can best highlight Shen Congwen's unique understanding of "death" is actually the third view mentioned above. In Shen Congwen's mature works, the theme of death is often visible. But death does not suddenly invade our daily lives, causing us fear and disgust; on the contrary, it becomes a commonplace everywhere in our daily lives. Death is not so much a shocking event as opposed to life as an organic part of life. In the third > of the < Candle Void, Shen Congwen once described a vivid memory:

I remembered a painful impression twenty years ago at a small dock somewhere in the middle of youshui. There was a veteran soldier, who had suffered from a very serious fever at that time, lying in a broken empty ship panting and waiting for death, and only said to himself, "I am going to die, I am going to die", the voice was very deep and sad, and it seemed extremely uncomfortable at the time. Gave him two oranges, felt very incomprehensible, why a person should die? Have you lived enough or are you tired of living? After a night, after dawn to see, the person is indeed dead, after death the body appears to be extremely thin, as if to express unwillingness to occupy more space for the living, the sunken black face has two flies crawling, oranges are still well resting around. Everything was silent, only the sound of microwaves on the surface of the water chewing on the ship board was broken, and this "past" was well preserved in my impression, living in my impression. In the eyes of others, it may be a little incomprehensible, because I think this lonely death is much more meaningful than the lively life of the same group of inexplicable people in the city.

This is certainly a painful scene, but in this scene, death does not strike in a shocking and dramatic way, causing shocks in the world of life; it does not cause strong emotional fluctuations in the young Shen Congwen, the only witness. The coming of death is almost silent and undisturbed; the deceased accepts his fate of dying, and when he dies, the world remains as calm as ever, as if nothing has changed, "the orange is still resting on his side", there is silence all around, "only the sound of microwaves on the surface of the water chewing on the ship's board is heard".

Beneath this calm, death unfolds with a confusingly complex meaning: is it that the world remains indifferent and blind to human suffering and death, or is death itself an organic link in the workings of the world and life that should be so unhurried? Or do these two seemingly opposite interpretations reflect exactly two opposite sides of death? Perhaps the meaning of death for the living is to make us feel eternally confused about the meaning of life and to ask questions? In the face of this "lonely death", the young Shen Congwen also appeared surprisingly calm, and even observed the face of the deceased quietly and calmly, and found that he "had two hemp flies crawling on his sunken black face"; this was almost a face-to-face gaze at death. In addition to his compassion for the dead, Shen Congwen had no fear or disgust in his heart, only a kind of confusion about death. Death inspired the young Shen Congwen to think about life, and this enlightenment to live to death made the death of this nameless veteran more valuable in the author's heart than the lively and chaotic life of the people in the city.

Shen Congwen and Zhang Zhaohe

Shen Congwen seems to have a special interest in death, but this interest is different from the obsession with the posturing of death in Decadent literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the West. If we follow Shen Congwen's standards, the latter is probably only a pathology of shallow, delicate, and pretentious modern urban civilization.

From Shen Congwen's childhood, death, even the most violent and cruel, has been part of his real life. However, to our surprise, this close contact with death, which began in the early years, did not seem to bring any serious shock trauma to Shen Congwen's psychological world. On the contrary, it made him learn very early on to calmly look directly at death as an unavoidable, but unavoidable, component of everyday life and the world of life in general. In His Autobiography (1934), Shen Congwen described the corpses of death row inmates he saw as a child in a very indifferent tone, no different from when he described other scenes or childhood experiences:

Every day at school, I hung the bamboo book basket on my elbow as usual, and there were more than ten broken books in it. Although I did not dare not wear shoes at home, as soon as I left the gate, I immediately took off my shoes and took them to my hands, and walked barefoot to the school. Anyway, time is routinely extra, so I always have to take a detour. If you walk from the West City, you can see the prison there, and early in the morning a number of prisoners came out of the prison wearing shackles and sent them through the yamen to dig the earth. If you walk past the place of the murderer, who has not yet collected the body, and must have been crushed or dragged into the stream by the wild dog, go over and look at the squashed corpse, or pick up a small stone and tap it on the filthy head, or poke it with a wooden stick to see if it will move. If there were still wild dogs fighting there, they picked up many stones in advance and put them in the basket, threw them at the wild dogs one by one, no longer passed, just looked at the distance, and walked away.

This kind of quiet death, or the stillness of the living to death, is constantly flashing in Shen Congwen's mature novel works, and there are many specific examples. Shen Congwen's unique understanding of death may be the key to unlocking his own dilemma in the pursuit of "abstract" "beauty". For contemporary readers, this knowledge of death not only highlights the finiteness of the individual's existence, but also points out the possibility for the individual to return to the natural operation of the individual beyond his own limitations and to establish a universal connection with the living world; however, this integration does not simply mean that the individual is completely one with the living world, and does not promise some kind of complete salvation, transcendence or liberation. By thinking about death, we are constantly in dialogue with the world in which we live, and in that dialogue we explore and construct the meaning of life.

▼Click here→ the QR code in the recognition map and download the "Reading in" app