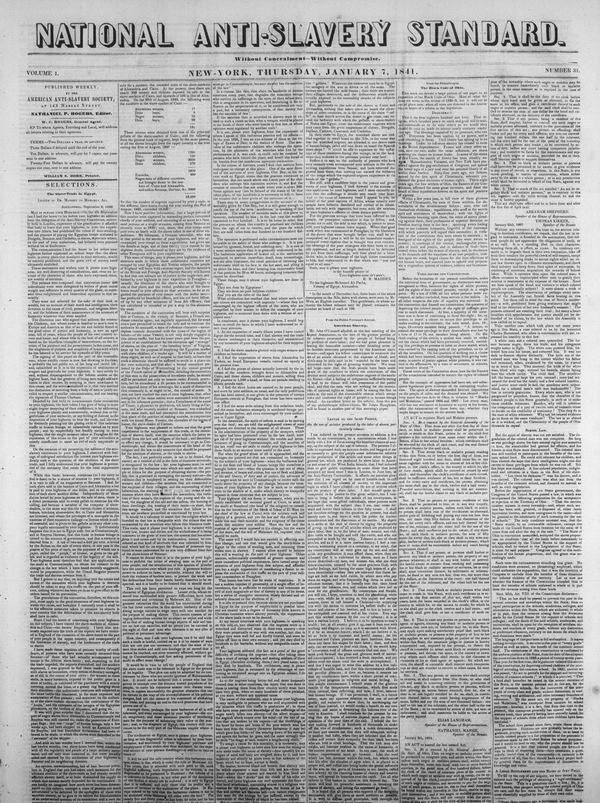

National Anti-Slavery Standard

In 1855, James Miller McGinn, a reporter for the National Anti-Slavery Standard, wrote that at the end of slavery, he hoped that the stories of those who had escaped and helped them would arouse the pride of all Americans:

These wonderful stories... This is happening right in front of the eyes of the American people, and one day they will be fairly evaluated. Although now people feel that these stories are not worth mentioning, but only the things of fanatical abolitionists, one day these revered heroic deeds, these noble and selfless self-sacrifices, these perseverance and martyrdom, these perfect divine arrangements, these life-threatening escapes and appalling adventures, will become the most widely circulated literary themes in this country, and future generations will sing for them, cry for them, bow their knees, and be indignant. (Fanner, The Freedom Trail: A Secret History of the Underground Railroad, p. 22, all quoted below are from this book.) )

Eric Fanner: The Road to Freedom: The Secret History of the Underground Railway, translated by Jiao Jiao, China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2017, 69 yuan.

One hundred and sixty years later, when historian Eric Fontaine quoted this historical material in his book "The Road to Freedom: The Secret History of the Underground Railroad", I wondered whether he would have foreseen that a year later, a novel also about the "Underground Railroad" would sweep through major lists such as the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, making this American past once again the focus of heated discussion.

Coulson Whitehead: Underground Railway, translated by Kang, Shanghai People's Publishing House, 2017, 39.8 yuan.

Both Fanner's scholarly works and Whitehead's best-selling novels can be seen as part of the "literary theme" of fugitive slavery since Uncle Tom's Cabin, and the underground railroad is undoubtedly the most legendary chapter in it. The Underground Railroad was a secret transportation network that pre-American Civil War abolitionists helped black slaves escape from slavery and flee to the northern Free States and Canada, a network of changing lines and connecting stations, into which countless ordinary people threw themselves into it. Before the smoke of the civil war had cleared, the "railway" had already appeared in the public eye, and the myth about it began almost at the same time. People who participated in the Underground Railroad wrote and published their own memoirs, and the collection and collation of oral histories gradually began, and novels, poems, plays, and works of art on this subject came out one after another. But, like the historian David Bright's study of civil war memory, the description and memory of the Underground Railroad is divisive, with white abolitionists and black abolitionists and fugitive slaves speaking their own words and even attacking and condemning each other.

This divisive narrative is also reflected in the discourses of later scholars. At the end of the nineteenth century, the underground railway began to become the subject of study by historians. In the pen of Wilbur Siebert and others, white abolitionists became heroes who, regardless of their own safety, organized and planned rescue of black slaves from fire and water. By 1961, Larry Galla had deliberately emphasized the agency of ordinary blacks, believing that the fugitive slaves had liberated themselves, and that "the orderly, free-flowing transportation system was a complete myth" (p. 11). This revised conclusion dominated the views of scholars for a considerable period of time. In recent years, research has shifted more to the local level and into the field of public historiography. After several generations of scholars' historical excavations and painstaking research, the underground railway seems to have no meaning left, and there is almost no "secret history" to speak of. But in Fanner's view, this singable history still has many obscure points that deserve "rethinking.". The book "Freedom Road" not only wants to clear up the myths and imaginations in literary works, but also to bridge the gap between different historical narratives.

Eric Fanner

However, Fanner had no intention of writing a complete history or general history of the Underground Railway, nor did he select a plantation or small town for microscopic analysis. He pointed out that the Underground Railroad was not as large and well-organized as previously imagined, "but a series of many local networks" that "encompassed a wide variety of individuals, opinion groups, and movements working to abolish slavery" (pp. 13, 17). Fonta chose to focus on New York City and the northeast. He begins by combing through the delicate relationship between New York City and slavery before the Civil War, and comprehensively examining the city's political, economic, legal, religious, and social atmosphere. Although Slavery was abolished in New York State in 1827, New York City was economically closely linked to the southern cotton and sugar industries, politically dominated by Democrats sympathetic to slave states, and legally repeatedly confirmed the right of slave owners to recover slaves as "property." Unlike Boston and Philadelphia, which have a tradition of anti-slavery, New York can be described as a fortress with a strong anti-abolitionist atmosphere.

It was precisely in this treacherous environment that since the 1830s, groups such as the New York City Alert, led by David Lagers and others, have been formed to take on the responsibility of receiving, hiding, and transporting fugitive slaves from the South. Because most of these activities are illegal, it is difficult to keep records, which has made it almost impossible to find a shadow of New York City in previous underground railroad studies. With the help of historical materials such as "Fugitive Slave Handbook" survived by Sydney Howard Guy, editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the author elaborates on the "node" and "hub" status of New York City in the northeast subway network. The city's abolitionist campaigns inspired similar organizations across the North, making New York City an important transit point for this "intercity passage" linking Norfolk, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Upstate New York, New England, and even Canada. Given that previous writings have focused on the Ohio Valley west of the Appalachian Mountains, Fonda's research is an important part of the East Coast Underground Railroad puzzle.

Sydney Howard Guy

The Fugitive Slave Handbook

Was the Underground Railroad an efficient network constructed by white abolitionists, or was it a "historical fiction" in which blacks rarely bailed out? Fonder argues that both of these tit-for-tat views are negotiable. Several of the major abolitionist organizations in New York City at the time were made up of whites and blacks, the latter often serving as important leaders. For the eventual emancipation of slaves, these groups had a similar vision, and contact and interaction were frequent. In his words, "The Fugitive Slave Rescue Organization was a rare example of interracial cooperation before the Civil War, and it also rarely linked urban underclass blacks with wealthy whites" (p. 16). However, due to multiple factors such as differences in specific strategies, financial disputes, and personal grievances, they are in a state of fragmentation in structure, even criticizing each other. For example, the main abolitionist organizations in New York City were divided into two factions, the American Anti-Slavery Association that supported William Lloyd Garrison and the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association led by Lewis Tarpin.

For a long time, another stereotype of the underground railroad was that the "railroad men" acted in secrecy and little was known to outsiders, which was often the content of literary works. In The Freedom Trail, many of the abolitionists' activities are not only secretive, but completely public. They relied on connections to help slaves flee to the North, hired lawyers to deal with judicial proceedings against fugitive slaves, raised funds to redeem slaves, and petitioned the legislature for a long time to protect the rights of blacks. In order to spread abolitionist ideas, influence public opinion, and thus gain more attention and funding, they founded newspapers, published pamphlets, leaflets and annual reports, and held speeches and fundraising rallies. Many northern politicians have openly supported these activities, especially the bazaars organized by women such as Maria Weston Chapman, which was once quite popular. In particular, abolitionists would resort to "direct action" by storming the courts and police stations, and forcibly taking away fugitive slaves by storming the courts and police stations and drunken jailers. Southern slave owners hired catchers to hunt down fugitive slaves, kidnappers kidnapped free blacks from the North, and abolitionists played cat-and-mouse games to cover up fugitive slaves, often played in New York City's harbors, stations, and hotels. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the situation faced by the abolitionist movement became more dangerous, and these open struggles intensified. By combining it with a larger historical context against slavery, The Freedom Trail expands the connotations of the concept of the "Underground Railroad" to a large extent. The Underground Railroad was not only a passageway to help black slaves escape, but also a series of activities in which blacks and whites cooperated to use moral, political, and legal means to fight slavery, freedom, and justice.

In these thrilling struggles, the words and deeds of abolitionists often attracted the attention of historians, while the voices of those fugitive slaves who were rescued were often ignored. Although a few famous fugitive slaves (such as Frederick Douglas and Hariyat Jacobs) have left their memories, the reader still asks: Where did the hundreds of ordinary fugitive slaves come from? Why did they run away, and in what way did they escape? What happened during the escape? Due to the lack of historical materials, most of the gaps in the past can only be hoped on the imagination of novelists. Thankfully, Guy's Fugitive Slave Handbook records the geographical origins, motivations, and methods of escape of more than two hundred fugitive slaves between 1855 and 1856 (including the story of Hariyat Tubman, who was about to board a twenty-dollar bill). Fanner compared this dusty manuscript with the classic historical records of William Steele and others, and restored as much as possible the fugitive slaves' ordeal journey to freedom: most of them came from Maryland, Delaware, and other places near the Mason-Dixon line, and there was no shortage of southern hinterland such as Georgia; the biggest motivation for fleeing the plantation was that they could not tolerate cruel corporal punishment, and there was also fear of being resold; they fled en masse in many cases, rather than on their own; they would disguise themselves and use trains, steamboats, and horse-drawn carriages to die. Even boxing himself by mail ("Man in the Box" Henry Brown). On the escape route of the sneaky crossing, they certainly received the full support of "underground railroadmen" such as Guy and his black assistant Louis Napoleon, but more help came from ordinary people, including white southern people who sympathized with fugitive slaves, Quakers who were staunch in faith, free blacks who were seafarers and dock workers, lawyers and judges with a sense of justice, ship owners who used the transport of fugitive slaves as a business, and so on. It is these individuals, who are unknown in traditional history books, who together pave this uncertain and ubiquitous path of freedom.

Hariyat Tubman

In short, on issues such as New York City and the underground railroad system, the composition and activities of the underground railroad organization, and the motivations and methods of slave escape, the book "Freedom Road" provides readers with many new insights and shows the specific operation of the underground railroad in detail. Using a contextualist approach, Fonder successfully dispelled myths and misconceptions about the Underground Railroad, balanced the tension between different historical memories, and wrote a touching story of "black-skinned and white-skinned Americans joining hands to advance side by side for a just cause" (p. 13). The success of the book lies not only in the excavation of new historical materials and the reinterpretation of old historical materials, but also in the narrative method of weaving these materials. The author skillfully and skillfully uses narrative history techniques to connect the whole book with vivid cases that are either heart-wrenching or exciting. The combination of traditional narrative history and "new American history" not only brings together the history of political debate, economic system, social opinion, ideology and other artificial divisions, but also enhances the drama and humanistic care of the story.

Of course, as someone who studies the American Civil War and Reconstruction, Fanner is not satisfied with telling a wonderful story, but tries to reveal the meaning of this story. The final chapter of The Freedom Trail returns to the old question that all scholars of nineteenth-century American history cannot avoid: Why did the Civil War break out? What role did slavery play? Who, exactly, freed the slaves? In other words, while the book focuses on the Underground Railroad in New York City, it is actually concerned with the grand question of the origin and nature of the Civil War. Fanner argues that, despite the sheer limited number of fugitive slaves before the Civil War, it was a focal point in the national political crisis surrounding slavery in the 1850s and was "a key catalyst for civil war" (p. 6). Abolitionist propaganda created an atmosphere of public opinion that awakened millions of northerners who sympathized with the fugitive slaves and obeyed their consciences. The rising number of fugitive slaves cost plantation owners dearly, ignited the anger of Southern leaders, and deepened the divisions of Republicans in the North, who had to face the paradox of slavery and freedom.

Lincoln's shift in attitude toward fugitive slavery may be seen as a case in this social climate. In the late 1850s, in order to maintain unity within the party, Lincoln adopted a more evasive and ambiguous posture on the issue of fugitive slavery, that is, recognizing the constitutional right of the South to recover fugitive slaves, but advocating an amendment to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. At the beginning of the Civil War, Lincoln still harbored the illusion of reconciliation with the South, and for a time ordered the Union army to return the fugitive slaves. By the end of 1861, the influx of fugitive slaves and the surging public opinion finally led Lincoln to declare that all fugitive slaves who had reached the areas occupied by the Federal Army would be automatically liberated. (For a more detailed discussion, see Fonda: The Test in The Fire: Abraham Lincoln and Slavery in America) Here, Fanner again "cunningly" fabricates past conflicting historical explanations: Who freed the slaves? Whether it is Lincoln, the "great liberator", the fugitive slave who "liberates himself", or the ordinary person who helps the fugitive slave, as an individual among countless historical parties, they have participated in and promoted this great process in some form.

Eric Fanner, "Tests in the Fire: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery," translated by Yu Liuzhen, The Commercial Press, 2017, $78.

Another "ambition" of Freedom Trail is not only to talk to experts and scholars in the field, but also to become a desk for ordinary readers. Compared with Fanner's other tomes, "Freedom Road" can be described as a "small book for everyone" with public historiography. With a sympathetic brushstroke, Fonda writes about the joys and sorrows of small people in the great history. Compared with Whitehead's cold and restrained writing, Fanner as a historian is sometimes more blunt and emotional. The novel "Underground Railroad" leaves readers with a suspense: will the protagonist Cora find her promised land? At the end of "Freedom Road", many runaway slaves who have worked hard finally enjoy a moment of joy of freedom. This slightly reassuring ending added a touch of warmth to the dark history of slavery and to a country that was once again anxious about race relations.

As a translation, the Chinese edition of The Freedom Trail restores Fonda's clarity and clarity, without lack of vivid and lively style, and it is not difficult to read. But the extent to which Chinese readers can truly understand this history and its significance is another question worth pondering. In the context of american reality, academic and literary works on racial issues are not uncommon; for Chinese readers without relevant historical experience, understanding American slavery, which has become a thing of the past, undoubtedly requires breaking through huge cultural barriers. Of course, this dialogue across the curtain of time and space is not without precedent. In 1901, Lin Shu "touched the yellow seed will die, so he will be more and more sad", and began to translate the "Black Slave Calling Heavenly Record" in the hope of "cheering up the morale and patriotically protecting the seed". The book has made young Lu Xun and others feel impressed, and has been adapted into a drama. In the 1950s and 1970s, when the Cold War was in full swing, works such as "John Brown" and "The Soul of the Black Man" by the black radical thinker Du Bois were translated into China and became popular. At a time when there is no crisis of national subjugation and extinction, and there is no longer solidarity with the "Struggle of Black Americans against Violence", we may be able to face the common spiritual heritage of mankind with a more "sympathetic understanding" mentality.

Lin Shu's translation of "Black Slave Calling Heaven"

DuBois: John Brown