This article was published in Sanlian Life Weekly, No. 5-6, 2020, and the original title was "The Love Story of Polonium and Radium", which is strictly prohibited from being reproduced privately, and infringement will be investigated

Marie Curie was the first scientist in the world to win the Nobel Prize twice, thanks to her great scientific achievements , the discovery and purification of the radioactive elements polonium and radium. From another point of view, polonium and radium are both products of the love of the Curies, which embodies a man's respect and recognition of his wife's scientific career.

Text/Zhang Jiajing

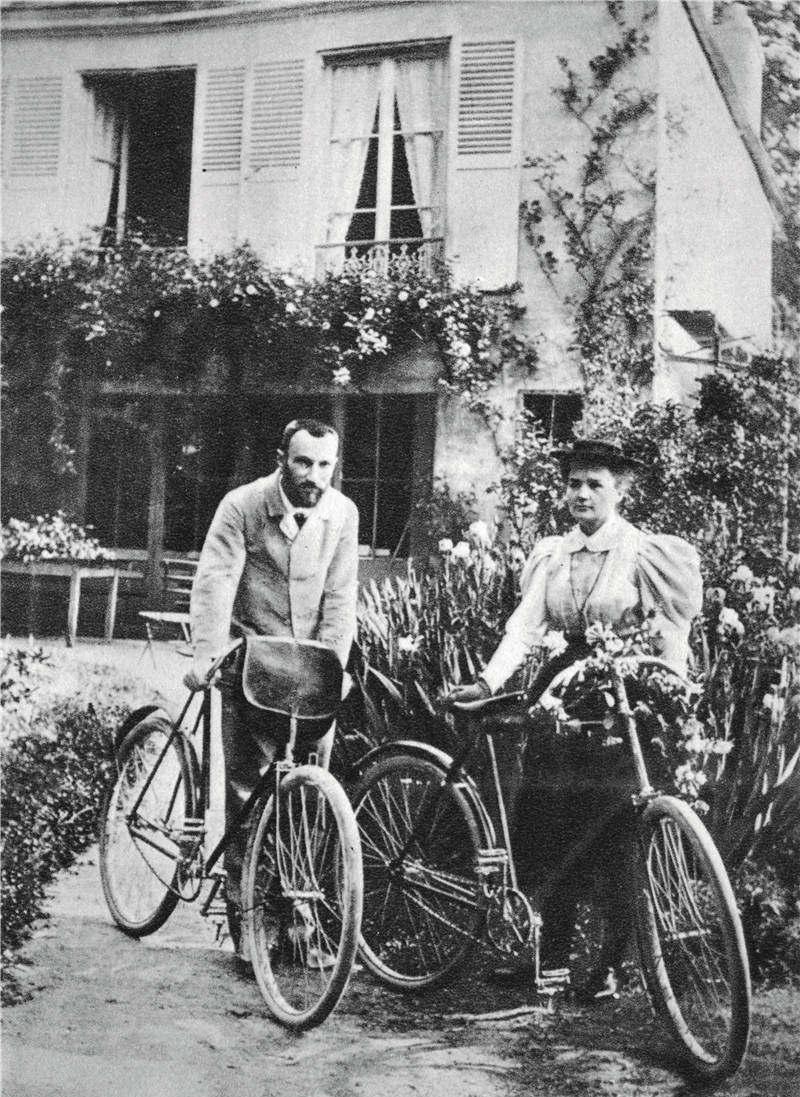

Maria Curie and Pierre Curie

In 1903, the Curies won the Nobel Prize in Physics, and Maria Curie became the first ever female scientist to win the Nobel Prize, which excited the public and the media. At the award ceremony, the President of the Swedish Academy of Sciences quoted a sentence from genesis in his speech: "It is not good for that man (referring to Adam) to live alone, and I will make a spouse for him to help him." ”

The Curies were overworked and in poor health from previous studies, and Marie Curie happened to be pregnant with her second child, and their trip to Stockholm was only realized in 1905. Under some "convention", Pierre Curie, as a representative, gave their academic speech.

To the great delight of those present, Mr. Curie was rigorously worded, and he paid great attention to distinguishing between Marie Curie's personal achievements and their joint research. "Marie Curie studied minerals containing uranium or thorium." He calmly recounted Marie Curie's pioneering work in the field of radioactivity research, "Marie Curie believes that these substances contain radioactive chemical elements that we have not yet recognized. ”

After the feminist movement grew in the 20th century, some considered the title "Marie Curie" to be a sort of insult to Maria, which deprived her of her independence as a female scientist. But in fact, despite the limitations of the times, Mr. Curie has always admired, encouraged and respected his wife, and they are rare companions who illuminate each other and leave a name in the history of science.

The love of two unmarried people

In November 1891, a 24-year-old Polish woman, Maria Skłodowska, entered the University of Paris. In order to receive formal higher education, Maria worked for several years before she saved enough money to board the train to Paris. She refused room and board from her sister-in-law, who lived on the outskirts of Paris, and lived alone in a small attic near the school.

Like many international students from Poland at the time, Maria's education life was poor and difficult. In order to save money and time, she often ate only bread, eggs and fruit for weeks to fill her hunger, resulting in anemia and fainting from time to time. Maria shuttled through classrooms, libraries, laboratories and attics year after year, earning a bachelor's degree in physics with honors in 1893, topping out among 30 test takers, and a bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1894 with a second-place success.

It was also in that year that she met the man who changed her life, Pierre Curie. The two became friends because of a mutual friend, the Polish scientist Kowalski. According to Maria's recollection years later, the scene of the first encounter between the two is romantic: "When I walked into the living room of the professor's house, I saw this young man. He stood right in the recess of a French window facing the balcony, like a painting embedded in a glass window. He was slender, his hair was russet, and his large eyes were clear and bright. His expression was flowing, and his expression was deep and gentle. When you first see him, you think of him as a dreamer immersed in your own thoughts. ”

Pierre, then 35, was already enjoying a worldwide reputation. He has dabbled in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity and other fields, obtained a master's degree in physics from the University of Paris at the age of 18, discovered the piezoelectric effect at the age of 22, invented the piezoelectric quartz electrometer at the age of 23, served as the director of the physics laboratory of the Paris Institute of Physics and Chemical Engineering (hereinafter referred to as the "Faculty of Physics and Chemistry") at the age of 24, and then turned to crystallization research, which is a pioneer in the study of crystal symmetry. In the year he met Maria, he also predicted the magnetoelectric coupling effect. Nevertheless, the genius scientist, who refused to accept any medals and had no intention of seeking a position, had been paid a meager salary, working for more than a decade, earning no more than 300 francs a month, which was comparable to that of a mechanic in a factory.

Both had been unmarried before they met each other, and the failed love affairs of their youth and the principles of life devoted to science made them instinctively wary of love. Curie, in particular, has the concept of "straight male cancer" in today's view, and the 22-year-old once wrote in his diary: "Women prefer to live for material life than we men, and genius thoughtful women are simply rare." Therefore, when we are driven by some kind of mysterious love and want to enter some kind of anti-natural path, when we are fully focused on the mysteries of nature, we are often isolated from society, and we often have to fight with women, and men are always in a weak position in this struggle, because women will pull our hind legs in the name of life and instinct. ”

Frederick Curie and Iren Curie

Curie was particularly wary of vulgar love interfering with his scientific career, until he met Maria, a Polish woman who also abandoned material pursuits and made science her highest cause. Because of her, Pierre fell in love. He visited her many times and talked to her about everything from crystallography research to childhood life. Within a few months, Pierre proposed to Maria, but the Polish woman, who was attached to her homeland, politely refused.

That summer, Maria returned to Poland to visit her father after completing her studies, and during this period of separation, Pierre wrote many affectionate letters, fearing that his dream lover would not return to Paris. "Hearing your news is my greatest joy, and it is difficult for me to accept that I will not hear from you for two months, after all, the few words you write casually will be greatly welcomed." I hope you have a good rest and come back to us in October. "I dare to fantasize about a beautiful thing, hoping that we can live our lives next to each other in our dreams: your dream of serving the motherland, our dream of happiness for mankind, and our dream of science."

When October came, Maria returned to Paris as promised, and the overjoyed Pierre proposed to Maria again, this time changing his strategy, first asking Maria if he would like to work with him as a friend, and then taking a step back, he was willing to go to Poland to earn a living, just to do scientific research with her. Not only that, Pierre also mobilized his mother to blow the whistle to Maria's sister and brother-in-law: "No one in the world is as good as our pierre." Tell your sister not to hesitate, she is much happier to marry my son than to follow someone else. Maria fell under Pierre's onslaught, and she agreed to marry Pierre.

On July 26, 1895, Maria wore a new navy blue wool dress—she had chosen a dark dress to wear in the lab later—and hosted a simple but heartwarming wedding with Pierre. Since then, Maria has had a title that is familiar today: Marie Curie.

Polonium and radium: the crystallization of career and love

In 1897, two years after their marriage, their first daughter, Irena, was born. Marie Curie had to face an eternal dilemma: how to balance the role of mother with her own career? Mr. Curie is his wife's staunchest supporter of her scientific career, and he often says that God created such a good wife for him so that she could share everything with him.

They chose to hire a maid and took Monsieur Curie's father to live with him. As for Maria's career, the Curies worked together on the latest physics works and chose a topic for Maria's doctoral dissertation in physics. The writings of the French scientist Henri Beckler attracted the attention of Marie Curie. After X-rays were discovered, scientists tried to determine the properties of such rays, and Beckair observed mysterious radiation phenomena while studying uranium salts. This completely untapped field became the subject of Marie Curie's research.

In order to solve the problem of the experimental site, Pierre negotiated with the rector of the Faculty of Physics and Chemistry many times, and only reluctantly won a simple experimental site for madame: a storage room wrapped in glass on the ground floor.

In the coming year, Marie Curie's scientific research will progress rapidly, first discovering that other elements are also radioactivity while studying uranium rays, and then discovering a new, highly radioactive element when examining many ores. These breakthroughs led Mr. Curie to suspend his research on crystallization and help his wife work together on the new substance.

That year, they discovered two new elements in the bitumen uranium mine, named polonium and radium, the latter of which is particularly valuable for scientific research in the treatment of cancer. This discovery has changed the structure of knowledge inherent over the centuries, contradicting entrenched notions of the composition of matter, and how can one interpret the natural radioactivity of these radioactive objects?

In order to further prove the existence of these two new elements and to study their properties, the Curies decided to purify radium. They first used their meager savings to buy a ton of uranium bitumen waste from a uranium refinery in Austria at a very low price, and then built a laboratory on a simple wooden shed provided by the Institute of Physics and Chemistry. There is a glass skylight full of cracks above the wooden shed, which always leaks water on rainy days, and the shed is hot and humid in summer and cold in winter. Due to the lack of necessary experimental equipment, the shed was filled with poisonous gas once the chemical experiment was started.

In order to ensure the progress of the experiment, the couple often made some food in the wooden shed as lunch. Marie Curie, who was responsible for refining radium salt, sometimes had to stir boiling industrial waste residues throughout the day with a large iron rod as heavy as her body. Sometimes, the dust floating in the room affects the crystallization and separation of concentrated radium, which bothers them. However, with a few walks around the small wooden shed and discussion, they will soon be able to regroup and re-engage in experiments. In Marie Curie's autobiography, she called the time they spent working together on research "the greatest and most heroic period of our common lives."

From the day they began working together, it was impossible to distinguish which part of the achievement was due to Maria and which part of the achievement belonged to Pierre. In their formula-laden work notes, the two men's notes are mixed together; in their published scientific works, almost all of them have signed the names of two men; and in these works there are words like "we found..." and "We observed..."

It can be said that the three elements of scientific research, conjugal life, and childbearing have achieved a perfect balance in the marriage of the Curie couple. In addition to the experiments, the Curies would ride their bicycles to the countryside, which was a recreational activity that they had been continuing since their marriage. At night, Maria coaxed the child to sleep and returned to her husband, and Mr. Curie, who was inseparable from his wife on weekdays, would eat the child's vinegar: "You don't think about anything but that child!" When the family had fallen asleep, they would walk arm in arm to the small wooden shed where they worked and observe the light emitted by the radium they had refined and separated.

Their youngest daughter, Eve Curie, portrayed the scene in The Biography of Marie Curie: "She carefully walked forward, found a chair with a straw mat, and sat silently in the dark. Both men's faces turned to those shimmers, to the mysterious source of radiation, which was radium, which was their radium. She leaned forward and bent her head, eagerly, in a posture like watching a child fall asleep an hour ago. Her lover gently stroked her hair. ”

This painstaking and enthusiastic research lasted for 4 years. In 1902, the Curies succeeded in extracting 1 decigram of particularly pure radium chloride. These radium chloride show the properties that radium should have and have a special spectrum that differs from other elements. They also determined the atomic weight of radium and had a lot of evidence of radium as a new element.

In 1903, Marie Curie successfully received her doctorate. As radium showed its unique role in treating cancer, the Curies' technology for purifying radium received attention from American technicians, who applied for information about radium making. They decided to abandon the patent for radium, even though it would bring them a lot of money enough to get a good laboratory. The Curies believe that only by making radium methods can the radium process develop as soon as possible.

In the same year, the Curies and Henri Becklele were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their study of radiation phenomena.

Moving forward in discrimination

However, Marie Curie's road to the Nobel Prize was not smooth. The only people who were initially nominated for the award were Mr. Curie and Beckell. The Swedish mathematician Magnus Gosta Mitag-Levler on the nominating committee was a rare fan of female scientists at the time, and he wrote a letter to Pierre to learn of the situation, and Mr. Curie, who learned of the situation, repeatedly emphasized the key role played by Marie Curie in radioactivity research in his reply to the committee, which enabled the Curies to win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903 at the same time.

Marie Curie struggled with sexism throughout her life: she graduated with honors from the University of Paris but could not find a suitable teaching position in her native Poland; she won the Nobel Prize twice but never became a member of the French Academy of Sciences. But Mr. Curie, he regarded Maria as a close friend, a working partner and a lover. Whether in the pursuit of Maria or after marriage, he always respected and recognized Marie Curie's values, abilities and ideals. It can be said that it is in such a progressive, pioneering, and equal love that radium has come out.

On April 19, 1906, a carriage accident took Mr. Curie's life, which became a turning point in Marie Curie's life. For the first time, Marie Curie was devastated by grief, and the heavy mental blow brought her to the brink of collapse. But a conversation Pierre had with her during her lifetime always inspired her: "Even if I'm gone, you have to keep working." Beginning in the autumn of that year, Marie Curie succeeded Hime curie as a professor at the University of Paris, and two years later she was hired as a professor.

At the same time, Marie Curie continued her research on radium while raising her two young daughters. In 1911, Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering two new elements, polonium and radium, as well as for the purification of radium. However, at that time, she was plagued by scandal in France. The news of her Nobel Prize was swept across the corner of the newspaper, but the headlines were filled with her scandal with a physicist, Paul Lang, who was 5 years her junior.

Lang Zhiwan is known in the scientific community for his research on paramagnetism and antimagnetism. He was not only a student of Pierre, but also a married husband with 4 children. After Pierre's death, Lang Zhiwan and Maria did develop a relationship in close cooperation, and without Lang Zhiwan, it would be difficult for Maria to get out of the shadow of Pierre's death, and it would be difficult to continue to promote the study of radium so smoothly. Lang Zhiwan's separated wife, a woman who had never received a good education, refused to divorce her husband, and sent someone to steal many of Lang's letters, including Maria's love letters to Lang Zhiwan. Mrs. Lang Zhiwan then made these letters public, and the scandal culminated. Angry French people gathered in front of Marie Curie's house and humiliated her as a "foreigner", a "thief", and a "Polish slut".

Fortunately, many of Marie Curie's friends helped her through the crisis, including her student Margaret Borrell, who argued with her father, Paul Eppe, dean of the Faculty of Physics at the University of Paris, saying: "If you succumb to the stupid nationalist movement and insist that Maria leave France, you will never see me again." Marie Curie's lifelong friend Albert Einstein also wrote to comfort her. In stark contrast, Einstein's private life was far more complicated than Marie Curie's, but there was little criticism of it.

In 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War, Marie Curie was reinvigorated in the public eye, devoting herself to X-ray and anatomy research, and to applied technology research on the front lines of the war, which helped a large number of wounded people avoid disability and alleviate suffering. In 1934, Marie Curie died of malignant leukemia due to long-term exposure to radioactive materials.

The story of the Curie family does not end there. The Curies' eldest daughter, Irena Joliot-Curie, and her husband, Frederick Joliot-Curie (Western women usually follow their husband's surname after marriage, and the couple adopted the method of combining the husband's surname in honor of Curie's great surname) together won the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of artificial radioactive materials. The Curies' youngest son-in-law, Eve Curie's husband, Henri Richardson Labuys, was awarded the 1965 Nobel Peace Prize as Executive Director of UNICEF.

Marie Curie's life, her love story with Pierre Curie may not be perfect, but their gifts to the world, whether polonium, radium or two excellent daughters, are worthy of being called great.

<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" > more wonderful reports can be found in this issue of "Physical Evidence of Love: Why Is This One So Important?" , click on the product card below to purchase</h1>

【Sanlian Life Weekly】2020 No. 5-6 Issue 1073 Physical Evidence of Love ¥30 Purchase