Source: China News Network WeChat

Editor's Note:

Is the Chinese nation one or more? Can the Western concept of nationality describe the "Chinese nation"? A few days ago, Pan Yue, the first vice president of the Central Socialist College, wrote an article about the public case of Gu Jiegang and Fei Xiaotong, two Chinese scholars in the last century. Excerpts from the article are as follows, with the title separately prepared by the editors.

Within every civilization, there are commonalities and differences. When the community is divided, the political centers, in order to demarcate their borders and consolidate themselves, are bound to exaggerate differences and belittle commonality until they become permanent divisions. Even if there are the same ancestors, languages, memories, beliefs, as long as there is political polycentric competition, this tragedy is bound to occur. Sects are divided, ethnic groups are disintegrating, and so is the case.

Political unity is the basis of the existence of cultural pluralism. The more political unity is consolidated, the more multiculturalism can stretch out its individuality; the more fragile the political unity, the more multiculturalism will fight each other and eventually die. Unity and pluralism are not one or the other, but the same weak and strong. If you do not understand the dialectical relationship between unity and pluralism, you will divide the world and confuse yourself.

The concepts of unity and pluralism were entangled in the two Universities of China in the last century.

Gu Jiegang

The first is Gu Jiegang. In 1917, the New Culture Movement created a group of fierce radicals, and Gu Jiegang was the number one. In 1923, the 30-year-old Suzhou youth lashed out at the Three Emperors and Five Emperors, believing that ancient history was "built" by Layer by Layer by Layer. He advocated examining everything by empirical methods, and whoever wanted to prove the existence of Xia, Shang, and Zhou must come up with evidence of Xia, Shang, and The Three Dynasties. He used sociological and archaeological methods to contrast ancient books with each other, "daring to overthrow all the idols in the 'scriptures' and 'biographies' and 'records'." This movement developed to the extreme, that is, "Xia Yu is a worm". Hu Shi praised this, "It is better to doubt the ancient and lose it, and not to trust the ancient and lose it." ”

Using this method, he proposed to deny that "the nation is out of unity" and "the region has always been unified." He believes that in ancient times, "it was only the recognition that a nation had the ancestor of a nation, and there was no recognized ancestor of many nations", "originally it was its own ancestor, so why call for unification"!

As soon as the "theory of doubting the ancients" came out, the ideological circles shook the mountains and disintegrated history, and the "Chinese identity" disintegrated. But Gu Jiegang didn't think so. In his eyes, only such a new approach can reconstruct the decaying 2,000-year-old genealogy of knowledge. Like the pioneers of the New Culture Movement, he strives to create a new China.

However, the first to question the history of ancient China was not Gu Jiegang, but japanese Oriental historians before World War II. At the beginning of the 20th century, these historians described the rise and fall of East Asian civilizations, the rise and fall of ethnic groups, and the rise and fall of states from the perspective of eastern peoples. Its representative figure, Shiratori Kuji, used empirical historiography to propose that Yao Shunyu did not really exist, but was just an "idol" invented by later Generations of Confucians. Gu Jiegang, who was originally influenced by Qianjia Kao's spirit, deeply obeyed the white bird Kuji and also shouted "Down with the ancient history."

However, while engaging in academic innovation, these masters of Oriental history developed a complete set of theories of "deconstructing China by race", such as the theory of "Eighteen Provinces of Han China", the theory of "China North of the Great Wall", the theory of "Manchu-Mongolian-Tibetan Return to Non-China", "The Theory of China Without Borders", "The Theory of Non-State in the Qing Dynasty", and the Theory of Happiness in the Conquest of Foreign Nationalities. This has become the predecessor of today's "new Qing history" concept in the United States, and it is also the basis for Lee Teng-hui and other pro-independence factions. The Oriental masters also believed that after the Wei and Jin Dynasties, the "ancient Han people" had already declined, and the Manchu and Mongolian peoples had the "Yidi disease" of arrogance and self-respect. Only Japan, which combines the brave spirit of the northern peoples with the exquisite culture of the Southern Han peoples, is the "end point of civilization" to save the evils of East Asian civilization. Japanese culture is a subsystem that has grown up under the stimulation of Chinese culture, and has the qualifications to undertake Chinese civilization, and the center of Chinese civilization will be transferred to Japan.

Gu Jiegang woke up. In the face of the flames of war in "9/18", he once devoted himself to Oriental historiography and finally understood the relationship between scholarship and politics.

In 1938, he witnessed Japan continue to provoke the independence of the Thai and Burmese languages in the southwest, and was shaken by Fu Si Nian's spirit, and finally rejected his theory of fame. On February 9, 1939, he went to the table with a staff and wrote "The Chinese Nation is One".

He opposed the use of "nation" to define the various ethnic groups in the country and suggested that it should be replaced by "cultural groups", since "since ancient times, Chinese have only cultural concepts and no racial concepts". In fact, Gu Jiegang put forward the concept of "nationality" here, that is, "the people who belong to the same government" belong to the same nationality, that is, the Chinese nation.

He took his origin as an example, "My surname is Gu, I am an old ethnic group in Jiangnan, and there is always no one who does not admit that I am a Chinese or a Han Chinese; but my family was still one of the Hundred Yue who cut off tattoos during the Zhou Qin Period, and at that time lived on the seashore in Fujian and Zhejiang, and it was really not Chinese to communicate with China." Ever since our ancestor King Dong'ou sent a message to the Han Dynasty, asking Emperor Wu of Han to move his people between Jianghuai and Jianghuai... We can no longer say that we are a 'Vietnamese nation' and not a member of the Chinese nation." He, who always believed that the "three generations of continuity" was fabricated by Later Confucianism, began to argue about the transformation of the Shang Zhou, "Even Confucius, a descendant of the Shang King, had to say, 'Zhou Jian is in the second generation, depressed in the Wen Zhao, and I am from Zhou'. He did not want to say, 'You are the Zhou people, we are the Shang people, we should remember the old hatred of the Zhou Gong's eastern crusades'; he loved the Zhou Gong to the extreme, and often dreamed of the Zhou Gong. "Imagine how arrogant this is, where there is the slightest narrow conception of race!"

After the publication of "The Chinese Nation is One," it sparked a famous discussion in which the skeptic was a younger anthropologist and ethnologist, Fei Xiaotong. He was 29 years old at the time, and Gu Jiegang was a fellow of Suzhou, who had just returned from studying in the Uk.

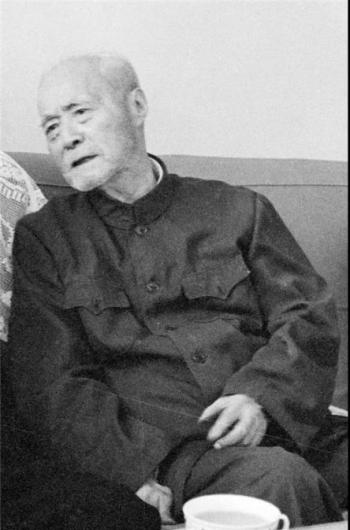

Fei Xiaotong

Fei Xiaotong believes that "nation" is a group formed according to differences in culture, language, and physique, and is a scientific concept. It is an objective fact that there are indeed different nationalities in China, and there is no need to deliberately eliminate the boundaries of various ethnic groups in order to seek political unity, and there is no need to worry about the enemy using the concept of "nationality" and shouting "national self-determination" to divide China. He stressed that "people with the same culture, language and physique do not have to belong to one country" and "no country need to be a cultural and linguistic group", because the reality of the Republic of China is that there are multiple political centers, and there are also many periods of political separation in Chinese history.

Hearing this, although Gu Jiegang was sick, he was like "a bone in the throat" and got up again to write "Continuing on the Chinese Nation as One", retorting that the "national nature" of the Chinese nation is strong enough and that "differentiation" is an "unnatural situation." As long as the separatist forces are slightly weaker, the people will spontaneously end the situation of division. If there had been natural stability in the "long separation," China would have been fragmented and not a nation long ago. He even roared angrily at the end of the article: "Wait, when the Japanese army withdraws from China, we can see how the people of the four northeastern provinces and other occupied areas have given us a good example."

For the anger of the seniors, Fei Xiaotong was silent and did not answer again. "Whether the Chinese nation is one or more" has become a public case with no conclusion.

Gu Jiegang died 41 years later (1980) at the age of 87. Eight years later (1988), the 78-year-old Fei Xiaotong delivered a lengthy speech entitled "The Pattern of Pluralism and Integration of the Chinese Nation." He acknowledged the existence of such a free entity as the "Chinese nation".

He said, "The Chinese nation, as a conscious national entity, has emerged in the confrontation between China and the Western powers in the past hundred years, but as a free national entity, it has been formed by thousands of years of historical process. Its mainstream is made up of a multitude of scattered and isolated national units, which, through contact, mixing, union and integration, but also split and die, form a pluralistic unity in which you come and go, I come and go, I have you, you have me, and each has its own personality."

After another 5 years, Fei Xiaotong returned to his hometown in Suzhou to attend Gu Jiegang's memorial meeting, and for the first time responded to the public case more than 60 years ago- "Later, I understood that Mr. Gu was based on patriotic enthusiasm, and in view of the japanese imperialism at that time establishing 'Manchukuo' in northeast China and instigating separatism in Inner Mongolia, so I filled my chest with indignation and vigorously opposed the aggressive act of using 'nationality' to split our country." I fully support his political position."

Some critics believe that Fei Xiaotong's "one-body pluralism" theory is nothing more than a compromise and bridge-up "political statement" between "one" and "multiple". However, Fei Xiaotong believes that the fundamental problem is that it is impossible to describe the "Chinese nation" with the Western concept of nationality. "We should not simply copy the existing concepts of the West to talk about China. Nation is a concept that belongs to the category of history. The essence of the Chinese nation depends on China's long history, and if the Western concept of the nation is rigidly applied, many places cannot justify themselves."

Fei Xiaotong also explained his transformation in his later years, "When I was circling in Qufu Konglin, I suddenly realized that Confucius was not engaged in the order of pluralism and unity. And he succeeded in China, forming a huge Chinese nation. The reason why China did not have the split between the former Czechoslovakia and the former Soviet Union is because Chinese have a Chinese mentality. ”

Konglin in Qufu, Shandong

The entanglement between Gu Jiegang and Fei Xiaotong reflects the common path of modern Chinese intellectuals - both the desire to use Western concepts to transform China's intellectual tradition, but the discovery that Western experience cannot summarize its own civilization; both the desire for Western scholarship independent of politics and the discovery that Western scholarship has never been inseparable from politics. In the end, they all returned to the matrix of Chinese civilization.

For more than a century, China has lost its political and cultural discourse power, and "historical China" is written by the West and the East. Brothers' perceptions of each other are shaped by foreign academic frameworks.

For example, there are Han chauvinist views that "there is no China after the cliffs and mountains" and "no China after the Ming Dynasty"; there are narrow nationalist views that "Manchuria and Mongolia returned to Tibet and non-China". This is all the poison of the "Oriental History" of that year.

For example, some historians have tried to use "ideology" to benchmark Western history. When the West said that "great unification" was the original sin of despotism, they blamed "despotism" on the Yuan and Qing dynasties. It is said that the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties were originally "enlightened despotism" in which "emperors and scholars ruled the world together", not far from the West, and as a result, they were transformed into "barbaric despotism" by the "master-slave concept" of the nomadic people, the high degree of centralization of power in the Ming Dynasty was a remnant of the military system of the Yuan Dynasty, and China did not produce capitalism because it was cut off by the Qing Dynasty. They come to this conclusion because they have not studied in depth the inner logic of China's failure to give birth to capitalism.

For example, when the West believed that China had not developed a democratic system due to the lack of a "liberal tradition," some historians began to argue that "agrarian civilization" represented despotism and "nomadic civilization" represented freedom. If the Yuan Dynasty had not been overthrown by the Ming Dynasty, China would have had a social formation above commerce and law as early as the 13th century. They did not understand that the honor of the "free spirit" belonged only to the Goths and Germans in the West, and never to the Huns, Turks, and Mongols in the East. In Montesquieu's writings, the same conquest, the Goths spread "freedom", while the Tatars (Mongols) spread "despotism" ("On the Spirit of the Law"). In Hegel's writings, the Germans knew all freedom, the Greco-Romans knew part of it, and the Orientals as a whole knew no freedom (Philosophy of History).

These disputes and attacks come from the fact that we always look at ourselves through the eyes of other civilizations, which, while having the benefits of pluralistic thinking, are often subject to the coercion of international politics. This has been true in the past, and it will be true in the future.

Chinese civilization is not without the concept of "race", but there is a stronger "tianxia" spirit that transcends it. Wang Tong, the great hermit of the Sui Dynasty, taught almost the entire general group of the early Tang Dynasty. As a Han Chinese, he said that the orthodoxy of China was not in the Southern Dynasty of the Han People, but in the Xiaowen Emperor of Xianbei. Because Emperor Xiaowen "lived in the kingdom of the first kings, received the way of the first kings, and the people of the sons of the first kings". This is the true spirit of the world.

The same is true of other ethnic groups.

Folklore of Lhasa, Tibet - Clay Sculpture "Golden Monkey Offering Peach"

Tibetans and Mongolians believe in Buddhism, and both Tibetan and Chinese traditions have the doctrine of "eliminating discriminating minds." In the Chinese Muslim tradition of "Yiru Huitong", there is also "the way of the saints in the western region is the same as the way of the Chinese saints." Its founding of the religion is based on righteousness, knowing the principle of the incarnation of heaven and earth, the theory of death and life, the principle of constant ethics, eating and living, not having the tao, and not fearing the heavens." This spirit of breaking down ethnic barriers is the background of Chinese civilization. A history of the Chinese nation is a history in which the "spirit of the world" transcends the "self-limitation of national nature."

The integration of the Chinese nation is also full of deep emotions. Written in the Mongolian "Golden History" written in the late Ming Dynasty, it is said that the Yongle Emperor was the widow of the Yuan Shun Emperor, and through the Battle of Jingnan, the Ming Emperor secretly returned to the Yuan Dynasty, until the Manchus entered the Pass, ending the "Mandate of Yuan"; the "Han-Tibetan History Collection" written in the early Ming Dynasty said that the Yuan Dynasty was "the Mongols who took charge of the han Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty", and the late Song Emperor (barbarian Hezun) did not throw himself into the sea on the cliff mountain, but went to Tibet to study Buddhism, became a senior monk of the Sassaska sect, and finally reincarnated as a Han monk named Zhu Yuanzhang, seizing the Mongol throne. He also gave birth to a son who looked like a Mongol named Zhu Di. The use of "reincarnation" and "cause and effect" to arrange the three dynasties of the Song Dynasty into "mutual past and future lives" is not a canonical history, but a legend of religious wild history, a simple consensus of people at that time on the greater China, and a different way for different ethnic groups to express the feelings of "community of destiny". These emotions are difficult for people who describe China based on foreign theories alone to understand.

Deep emotions can produce deep understanding, and deep understanding can complete the construction of reality. In the end, the story of the Chinese nation must be written by ourselves.

(Source: China News Network public number; Pan Yue)