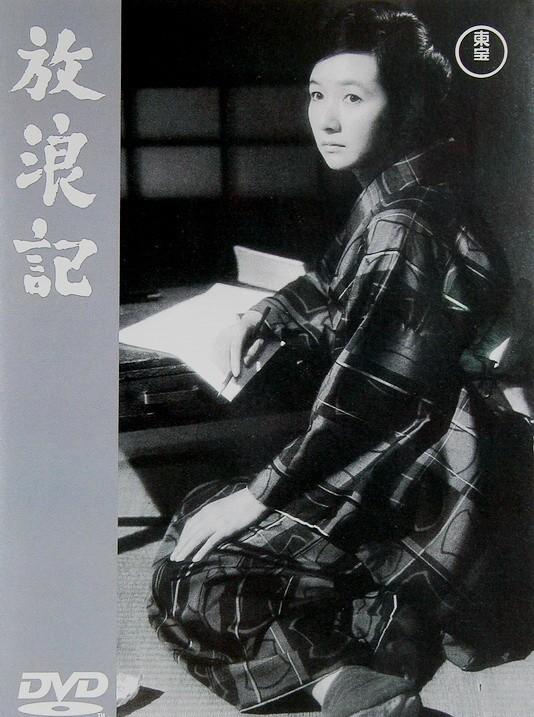

Film "Liberties/Liberties" (1962) Japanese DVD edition cover

Naruse Mikio (1905-1969) made the 1962 film Libertine/Libertine (1962), which was based on the autobiographical novel of Fumiko Hayashi (1903–1951), but it was not an adaptation of the work. Fragments of Fumiko Hayashi's text appear on the screen as subtitles, and are narrated by Hideko Takayama (1924-2010), who plays Fumiko Hayashi, in the form of a voiceover narration, but the story of the film is based on a play written by Kazuo Kikuda (1908-1973).

The drama, which has been playing out in Tokyo since 1961, is based on a biography of Fumiko Hayashi and is essentially different from Hayashi's autobiographical work, The Book of The Wave, which is based on events in the 1920s. The film is far less remarkable than Yoshio Naruse's previous adaptations of Fumiko Hayashi's works, even though he was unquestionably asked to direct based on his successful adaptations of Rice/Rice/Rice/Ino(1951), Ina/稲 Wife (1952), Late Chrysanthemum (1954), and Floating Clouds/Floating Clouds (1955).

According to film critics Shigehiko Ren and Sadao Yamane, the film is more of a Toho film than a Naruse miki film because it was made to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Toho's founding. (In fact, it was a Takarazuka film founded in 1932 and later merged into Toho in 1937.) The film came under intense criticism when it was screened for its conservative overtones.

According to Japanese sources, Fumiko Hayashi is regarded as a heroic pioneer of Japanese women's literature. She was very creative and escaped the poverty of being the inspiration for her first works by writing, becoming a very successful professional woman. This is basically a film version of Yoshio Naruse's story, but the focus of literature is on Fumiko Hayashi's skills as a writer, while the film emphasizes the hardships she endured in her career.

Female writer Fumiko Hayashi

In many ways, Hayashi herself is not a good fit for a film because it is essentially a text associated with an act. Writers become writers through their own labor. "The Liberties" is a woman's diary that not only supports herself through writing, but also, literally, she also feeds herself. Hunger and food fantasies constantly appear in the text, and she sells texts for food to satisfy these cravings. Fumiko Hayashi's romantic relationship, mainly with some untrustworthy and willful contemporary writers, cannot be separated from her network of editors and publishers who sell articles for money for a living. Fumiko Hayashi's work is clearly erotic and sensual, and she candidly writes about her experiences as a waitress in a café on the edge of the sex industry, including the variety of small people she encounters as she wanders around the city.

Stills from the movie "Libertine/Libertine" (1962).

The time in the novel is limited to the 1920s, which is the years that Hayashi Fumiko strives to become a writer, but the film extends this time to the time when the novel was published, including some scenes before the beginning and end of Hayashi's life. Naruse's version of "The Book of The Waves" begins with and ends with a scene of a young girl wandering in the countryside with her business parents.

The cyclical nature of the narrative inscribes a fatalism of the writing order very different from the detached, open-end novel. The addition of scenes depicts the novel's debut in 1930, some set near the end of her life (she died of cancer in 1951), when Fumiko Hayashi was a wealthy white-haired woman. The diary itself is thus framed by The Life Story of Fumiko Hayashi, and the immediacy and spontaneity of the archetypal characters are placed in a closed system.

Character poster for the Japanese version of the movie "Libertine/Libertine" (1962).

The distinction between fiction and film may be comparable to the difference between Benjamin's storytelling craftsmanship and the novel's focus on death as "the meaning of life." For Benjamin, these two forms correspond to different patterns of experience and memory: "The constant memory required by the novelist contrasts with the short-term memory form of the storyteller." The former is dedicated to a hero, a journey, a battle, while the latter describes many rambling events. "The novel is individualistic, while the story of the storyteller is embedded in the collective. The novel offers the reader the hope that "the death of someone he reads warms his own shivering life", while the storyteller allows "the wick of his life to be slowly burned by the soft candlelight of his story".

Movie "Liberties/Liberties" (1962) Japanese content flyer

Fumiko Hayashi's work is likely to be autobiographical and confessional, yet it is also ethnographic; and, because of its serialization, its rewriting, its appeal to the masses, it cannot be incorporated into any single or unified experience, similar to the kind of story that Benjamin attributed to the storyteller.

In addition to the compositional techniques added to the film, a small character in Hayashi's work becomes a larger and more portrayed character in the film. Nobuo Tseioka (Daisuke Kato) is a neighbor who lives in the same rented house as Fumiko Hayashi and her mother (Satoshi Tanaka). He is a benevolent single man who takes out his food to share with the mother and daughter and lends her money when Hayashi needs it, and offers to marry her.

The film "Liberties/Liberties" (1962) Japanese video version of the cover

The character, titled Matsuda in the novel, appears only briefly, and to him, the narrator of the novel says, "He is the epitome of everything I despise: an overly generous man." She accepted a small sum of money he had lent her, but their brief relationship was afflicted by embarrassment and mistrust. In the film, Nobuo Tsuneoka returns at different stages of Hayashi's life to witness her first husband beating her, and in the penultimate scene of the film, visits her in her well-furnished home and courtyard. His role in the film resembles that of a guardian or moral authority, witnessing The trajectory of Hayashi's life from desperate poverty to an upstart.

Stills from the movie "The Tale of the Waves/The Tale of the Waves" (1962), from left to right: Hideko Takayama, Mitsuko Kusanagi, and Yunosuke Ito

Fumiko Hayashi followed three men in her life. The first is a handsome-looking poet, who looks elegant and extraordinary, but is actually a small white face with no virtue and no talent. While getting engaged to someone, he cheated on eating and drinking from Fumiko Hayashi, and finally abandoned both of them. The second is a friend in literary circles and a poet, who is less talented than Hayashi Fumiko, and her submissions are repeatedly frustrated, while on the other hand, Hayashi Fumiko's manuscripts are often accepted by newspapers and periodicals in exchange for the cost of subsistence. At this time, the man's self-esteem was hurt, from the indifference to his wife to the final suspicion of the big fight, which destroyed the two people's peaceful and happy family. The above two types of men can be said to be common in today's reality, and their behavior and mentality can be found everywhere.

Poster of the Japanese version of the movie "Libertine/Libertine" (1962).

Fortunately, the last person to come together with Hayashi Fumiko is an honest man who also comes from the lower class, and The second half of Hayashi Fumiko's life can gradually return to peace. Interesting is the enthusiastic neighbor played by Daisuke Katong. From the euphemistic pursuit after the initial loss of his wife, to the help he needed later, to the final relief of the past, he is really a gentleman who is worthy of trust. A conversation between the two at the end of the film is also very interesting, and from time to time during the conversation between the two people asked to see Hayashi Fumiko, and Hayashi Fumiko mostly refused. Not because of the arrogance and indifference after fame, but because of the belief that the rescuer must save himself or herself in order to truly get rid of suffering - this can also be regarded as a sublimation of the film's intention, which can also be said to be universally applicable in the past and the present.

Aesthetically, Naruse's interpretation of The Book of The Wave does not meet the standards of formal innovation he previously used to capture the energy and agency of Fumiko Hayashi's work. It lacks the spatial unity of the family dramas "Rice", "Rice Wife" and "Wife" (1953) and "Late Chrysanthemum", and it also lacks the fluidity and dynamic transience of Floating Clouds. The omitted narratives are combined with fragments of Hayashi Fumiko's texts, and most are chosen because of their narrative messages rather than their poetic commentaries.

Some scenes almost disintegrate so much information because they as dramas do not produce the desired effect. For example, Hayashi moves in with a poor poet named Fukuji, but in the first scenes they are together, he immediately exhibits a wayward and superior personality, and the viewer wonders if she has seen him before.

The performance of Hideko Takayama, who plays Fumiko Hayashi, is probably the most stylized rendition than any of her previous roles in Naruse's films. In the café or tea room where Hayashi works as a waitress, she is as stunning as the alcoholic and fun-seeking woman depicted in Hayashi's novel.

She sang and danced, won a drinking contest, and did not hesitate to criticize the abuse of the woman by her guests, which inevitably offended the hostess. Aside from these few scenes that appear in the film, for most of the film, Hideko Takayama shows a listlessly frustrated posture, her body language and endless frowns revealing a gloomy sense of frustration. When Fumiko Hayashi is awake, this expression is rarely interrupted, so the entire film shows Hideko Takayama's "span of acting style".

Inside page of the brochure for the film Libertine/Libertine (1962).

In fact, she has only three expressions: happy, sad, and drunk, the second of which takes up almost two-thirds of the film. When she smiles, just as the sun comes out, but in the film she smiles only once, when several poets come to visit her in the café where she works and praise the poems she has written. Fumiko Hayashi smiled, and then a verse from the novel "The Book of The Wave" appeared in the form of subtitles in the scene she wrote at home: "I am a red jasmine flower dug out of the field." When the strong wind blows, I fly like an eagle into the wide blue sky, oh, the wind! Let out your fiery breath! Hurry up, hurry up! Blow up this red jasmine! ”

One explanation for Shuko Takao's unusual performance in the film "The Book of The Wave" is likely to be that Naruse's attempts to emulate the style of silent films.

Dvd cover of the movie "Libertine/Libertine" (1962) Taiwanese version

In fact, there are several scenes in which there is no dialogue at all, with Hideko Takashi reading aloud the messages from Hayashi Fumiko's novels in a voiceover. The widescreen format is not suitable for representing any such techniques, suggesting that this is the aesthetic of narrative forms and techniques that emerged in the 1960s. Moreover, the expansive composition creates an open space that is not suitable for stories of poverty or in disharmony with the "feelings" of the 1920s. This is very different from the fast montages and enthusiastic camera movements of Naruse's own silent films.

Leaving these comments aside, Akio Naruse's "The Tale of the Waves" captures some of the materialist aesthetics that are so distinctive in Hayashi's work. Hayashi's struggles are placed in a very delicate depiction of material scarcity, urban geography, and a working environment for women.

She often makes item-by-item records of the foods she craves and the foods she can find, which becomes the punctuation point of the narrative: pickled radishes, pork chops, noodles, Akita rice, eggs, curry rice, and fantasies about steaks and sushi. Fumiko Hayashi uses the money she earns from her writing to prepare meals for The Blessed Land. She listed the ingredients and their prices: "five dollars for tofu, three dollars for dried sardines, and two dollars for pickled radishes," but Fukuji rudely threw the dishes on the ground and took the money from her hand to buy cigarettes. Banknotes and coins appear in the constant exchange of small amounts of money, usually carefully placed on tatami mats.

The job that Hayashi applied for and the work she actually did constituted a generalization of the possible employment opportunities for women during that period: accountant (she did a very poor job and was not properly trained), factory work (making toys), working as a waitress (and waitress in a tea room), and finally a possible job in the theater, which eventually became a relationship with an unreliable theater director, hayashi said in a voice-over, saying that he "needed my body more than my resume."

On the set of the movie "Liberties/Liberties" (1962), The left is Hideko Takayama, and the right is director Naruse Mikio

The most uncomfortable thing about Yoshio Naruse's version of "The Book of The Wave" is that the "garbage" in Hayashi Fumiko's life was not "pulled up with a stick", but was commercialized. Far from being "naked," this truth has become stale, sentimental, and packaged as a legend of sadness and moral condemnation. The film points to the multiple forms of exploitation that Hayashi and other women suffer, but its underlying social critique is severely weakened by the film's lack of support for the protagonist's fundamental challenge to social behavior patterns.

The stylistic advantage of this challenge is in turn lost to the "wrapping" impulse of commodity capitalism, where The story of Hayashi Fumiko's life is no longer a self-performance, but a sad tragedy. What the film reveals is the vast gulf between the modernism of the 1920s and the crude sentimentality of the 1960s , which proves the decline of the studio system and its place in Japanese modernity.

Poster for the Japanese re-release of the film "Libertine/Libertine" (1962).