When it comes to Japanese literature, Yukio Mishima is undoubtedly a peak that is too eye-catching. Along with Proust, Joyce and Thomas Mann, he is known as the four great writers of the 20th century, twice shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and Americans even call him "Japan's Hemingway".

Different from the style of "love over reason" in traditional Japanese literature pioneered by The Tale of Genji, Mishima literature presents the characteristics of "both reason and reason" after integrating the classical aesthetics of Japan and the philosophical speculation of ancient Greece. From the concept of "beauty to the extreme is destruction" in "Kinkakuji", to the description of the wild and fiery lust of men and women in the work of pure love "Chaos", from the self-analysis in the semi-autobiographical "Confession of the Masquerade" to the reincarnation of the long "Sea of Plenty" tetralogy, all of them have left ideal writing about beauty and violence in the hearts of readers.

In addition to beauty and violence, the mysterious changes in Mishima literature have also sparked many discussions. In November 1970, Mishima ended his life with self-cutting, which formed a kind of implicit match with his creative style. Nine months before the cut, Mishima gave his last interview in conversation with John Bester, the English translator of his work, which was translated for the first time in China.

During the conversation, Mishima responded to questions about his literary creation in a frank and humorous tone, and confessed that he really could not write "vast river-like works", and the dialogue between the two gradually extended to the overall observation of postwar Japanese literature, and then to the undercurrent that surged within postwar Japanese society. From this, we can get a glimpse of the Japanese national writer's deep reflection on self and society.

The following is an excerpt from the last chapter of "Fountain in the Rain" "Yukio Mishima's Unpublished Interview and Confession" with the permission of the publishing house, and the length is reduced from the original article.

Original author | Yukio Mishima John Best

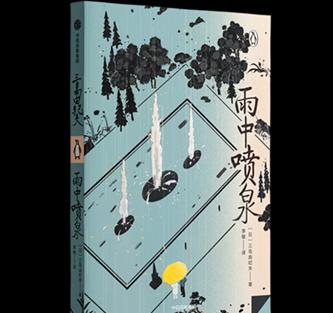

"Fountain in the Rain", by Yukio Mishima, translated by Li Min, CITIC Press, March 2023.

The weakness of Mishima literature

Best: I wanted to ask a strange question. In Mr. Mishima's eyes, do you have any shortcomings or shortcomings in your literature?

Mishima: Is there anything missing in my work? Let me think......

BEST: Actually, this may be a pointless question. You don't need to think about it, just take it literally.

Mishima: (After thinking for a moment) People are always aware of their own shortcomings when creating, feeling powerless in one way or another, and then making choices. I think the downside of my literary work is that the structure of the novel is too fluctuating and too dramatic. It stemmed from an urge I couldn't suppress. Even if I wanted to write a novel in the style of Virginia Woolf, I couldn't write it anyway. I can't reflect reality or my own psychological feelings into the article as they are.

Everything in my articles has been shaped by me. In this way, it will not be a realistic sketch, and it will not be possible to transfer it year-on-year. I'll definitely filter in between. In a sense, writing fiction is not meant to be. Reality flows into the novel as it is, in which there are many changes, and the changes that occur in the characters are beyond the reach of the author, perhaps this is the ideal state of the work. But I can't. What I wrote must have been conceived in advance.

Best: Although they are both novels, there are actually many genres.

Mishima: Yes, yes, but mine is too dramatic.

BEST: In Mr. Mishima's opinion, how can it be called an ideal novel?

Mishima: If I'm ideal, I've always looked at architecture and music as ideals, so I always feel that the closer I get to them, the better the work. I would be very happy if I could write cathedral-style novels, but I can't write works like vast rivers.

BEST: Isn't there such an example in traditional Japanese literature?

Mishima: I think that the so-called Japanese are weak in organizing articles is not true. Just like although it is not a novel, such as "Temple House" and "Meibeishan Women's Court Training" in Jing Liuli, they all show very excellent article organization skills. The structure of the work is extremely complex and very much within the reach of the human mind. And the effect is immediate, the article is excellently written. I wonder why this ability has not been popularized in Japan. Ma Qin is also a writer with excellent writing and organizing skills, but he is not much respected today. Perhaps because The Tale of Genji is a great work, its influence continues to this day, but even The Tale of Genji is not without structure. The work presents not a simple direction of life, the author has laid a very detailed foreshadowing in it, and there are many complex ideas. But these tend to go unnoticed.

The Tale of Genji, [Japanese] by Shikibu, translated by Feng Zikai, People's Literature Publishing House, August 2015.

Most Japanese don't really like what to make or build, they like the feeling of flopping and letting go.

But I think that, in a sense, this is the age of architecture. You see, only architecture developed significantly in Japan after World War II. Literature is not eye-catching, drama is not eye-catching, fine arts and music are not eye-catching. Only architecture. In this way, what I am doing does not seem so out of touch with the times. Perhaps on "Japanese-style architecture", it competes with Kenzo Tange. (laughs)

When I write articles, I paint them all over. That is, I will paint the article with color like an oil painting. I can't do Japanese white space in my creations. I know this weakness of my own. You imagine a Japanese painting with blanks that I can't tolerate, and I color them all. I'll paint it all over. Because I mind white space, I don't let them exist. If Mr. Kawabata's article is sometimes likely to have the effect of sleeping pills (laughs), there will be a big jump. In his article, the magnitude of the jump is really scary. I have written a review about Mr. Kawabata's "Yamain". It's terrifying. He flew to the next line with a bang, and there was nothing in between. I really can't write such an article, it's too scary.

The material for the novel is phrasing

BEST: When Mr. Mishima compares his own literature to other Japanese literature, does it make you think there is a huge difference?

Mishima: In short, it's a matter of wording. From the beginning of my creation, I firmly believed that phrasing was the skill of the novel, the material for it. I still think so. The material of the novel is not life experience or ideas, but wording.

BEST: In that sense, it's very similar to music. For pure art, such material is extremely valuable. But the novel is not pure art, so the common idea is that the material is not important. Flaubert thought deeply about this, but it was the wealthy rentier class of the nineteenth century, and such ideas no longer exist. He once cherished words, but such ideas are dying. I still have this kind of thinking, so I am a laggard of my time. Hahahahaha. Outright laggards.

BEST: In Mr. Mishima's opinion, what are the traditions in your articles?

Mishima: In my work, I deliberately use very traditional grammar. There is a dual form called "Four Six Qiuli Li Wen" in ancient Chinese, and I hope that this style can be used well in modern texts, so it is often reflected in my creations. As for ancient sayings, such as "Spring Snow", it is a novel that restores the literary genre of the dynasty, so there are many ancient sayings that are not used in daily writing, which I skillfully and deliberately.

Spring Snow, by Yukio Mishima, translated by Tang Yuemei, Shanghai Translation Press, August 2010.

BEST: Influenced by Western literature?

Mishima: The structure of the article is somewhat influenced by Western literature.

Best: So the wording itself is not affected by...

Mishima: I don't understand Western languages. If you don't understand, there will be no impact.

Best: When I translated Mr. Mishima's article, I was surprised by how it was presented as it was. (laughs) It's really strange that even if it is completely literal, it becomes a standard English expression. Maybe I'm not good at it, but you can see what I mean.

Mishima: People laugh at that. For example, Abe Kobo-kun is a typical international writer who claims not to be a nationalist writer, but some say that his way of thinking is in a sense Japanese, but he is considered a nationalist Mishima and thinks more like a Westerner. It seems that this writes the more common voice of the people. I agree with that. It was only after I traveled to Western countries many times that I began to think about Japan. In other words, after learning a little about the structure of Western thought, I felt that I gradually began to understand Japan. Before that, I didn't know much about Japan. (laughs)

Best: I totally understand.

Mishima: I'm western in terms of wording and so on. But after all, it is Japanese, and it is a word in Japanese. The words themselves have a beautiful feature of the Japanese language that we have been familiar with since childhood, and I use it. In this regard, the most typical of my works is "Tsubaki Says Bow Zhang Yue". Many Japanese expressions are used today, which are no longer used. I chose as beautiful expression as possible, and wrote the counterpart as if it were poetry.

Best: I originally wanted to ask this question in a later part, but because of the situation you mentioned, have the younger generation in Japan ever said that Mr. Mishima's article is "difficult to understand" or "I don't want to read it with difficult words"?

Mishima: Not at all. I would read letters from high school students who said that I was very happy that some difficult words were used in my work.

Best: That's really gratifying.

Mishima: The letter says that reading while looking up a dictionary is a pleasure. And there are expressions in the works that I can't learn in school, so I feel happy.

Best: There are young people who think this way.

Mishima: Yes. The letter also mentioned that I am very happy that the old kana usage has been preserved in my article. Today's young people are rebellious and resistant to what is taught in school. They think that what school teachers teach is a lie, and that what is not allowed by the teacher is correct. Yukio Mishima, a novelist, says things that the teacher does not approve of, and uses expressions that the teacher does not use, so he likes him. That's my young fans. (laughs)

A still from the movie "The Biography of Yukio Mishima" (1985).

BEST: However, will the teaching content in Japan gradually develop in this direction?

Mishima: It's hard to say, I'm skeptical. Classical education in Japan has been in decline since before World War II. I think that under the rule of Meiji officials in Japan, the content of education became more and more unbearable.

Best: In this sense, if you look at the world, Japan should also be counted as a special case, right? In terms of language.

Mishima: Extremely rare. You know that Japanese education is controlled by bureaucrats. Bureaucrats, on the other hand, are a group of people who do not know the language and culture, but such a group of people play with education. Moreover, the Japanese have always been taught in a way that is completely unable to appreciate the value of classical literature.

Classicist education is still practised in France today. I think that we should follow the old "read a book a hundred times and see its own meaning", even if you don't understand the meaning, you should first memorize it. Otherwise, we will definitely not be able to get close to the classics. An extreme example is teaching The Tale of Genji to elementary school students. Even if you don't understand the content at all, you have to recite excerpts from The Tale of Genji like a sutra.

Best: Even so...

Mishima: Even so, it's valuable. But this practice was not implemented, so people's Chinese education became weaker and weaker. Moreover, the stylistic structure of the Japanese language has become extremely thin.

BEST: Maybe the school is doing its best.

Mishima: Maybe. But when I was a student, I no longer adopted the orthodox teaching method of reading aloud. In fact, to learn Chinese, you still have to memorize the Analects, no matter how painful the process. Only in this way can the structure of the article in Chinese be imprinted in the mind. Nowadays, people's writing ability is weakened, and this is precisely the reason. Without a Chinese upbringing, Japanese articles became very crumbling.

Best: So it seems that there is no other way to write a good article than Mr. Mishima's approach.

Mishima: This is just my personal hobby, not to recommend it to everyone. I wanted to take the best of Japanese and Chinese, take my favorite words, and use them only to make bouquets.

Postwar Japan's "hypocrisy"

Mishima: The people I hate most about dealing with are novelists. Be very careful throughout the year, and don't meet a novelist. I would never go to a restaurant that flattered me and said, "Teacher so-and-so frequents the small shop." I especially hate being introduced like that.

Moderator: So you don't have much interaction in the literary world...

Mishima: Extremely disgusted. But sometimes it is a last resort. If there is no way to participate in literary prizes and the like, it is once, twice, two or three times a year, when you have to show your face, and then quickly run home. I wasn't like this before, and I had a vision of a scribe when I was young.

(A second glass of whiskey soda is delivered at this time)

But it is precisely because I speak unscrupulously that I cannot become a famous master. This cannot be done in Japan, where there are many taboos. I may be very similar to Westerners.

BEST: What do you particularly dislike about modern Japanese society?

Mishima: It's hypocrisy. hypocrisy。

Best: But about this, the West also has Western ones ...

Mishima: The West does have a tradition of outright hypocrisy. Britain, in particular, has a solid tradition of hypocrisy. Recently laughed with the British. "Mishima, you're a traditionalist." "Yes." So the Englishman said, "Then you must be averse to hypocrisy." "That's right." He added, "We are a hypocritical nation. "But you can be both a typical traditionalist and a hypocrite, and because your country has a glorious cultural tradition of hypocrisy, you can have both." But the Japanese cannot be both traditionalists and hypocrites. "There is no such tradition as hypocrisy in our country.

BEST: You say that Japan today is a hypocritical society, and this phenomenon has only recently begun?

Mishima: After the war ended, it started to get worse. It seems to me that I am terminally ill.

BEST: In what particular way is this Japanese hypocrisy?

Mishima: Peace Constitution. That is the source of hypocrisy. This can be asserted from a political point of view. In the old days, the Japanese lied and were full of lies. Many hypocritical words have also been said. But those are the needs of traditional morality, that is, in some cases, it is necessary to lie; Never tell the truth to someone.

Best: Japanese hypocrisy can be said to have been formalized or ritualized, so it doesn't hurt to do so. Because it is recognized by society, everyone lies calmly.

Mishima: Very calm.

Best: But in our view, this ethos continues well today.

Mishima: Maybe it does continue a certain vein.

BEST: Not by ironic hypocrisy, but rather as a good thing.

Mishima: This involves the question of whether people should always be honest. For example, it is difficult to judge whether cancer patients should be told the truth. Sometimes we have to lie, and lying is also a kind of care. In my opinion, hypocrisy is a kind of self-satisfaction. In human relationships, let's take you as an analogy, I don't know if you have a wife, let's say, she is very ugly, I can say it so calmly because I have never met her, let me say "Your wife is really ugly". This may be true, but it is not human. As your friend, even if I see your wife ugly, it is only understanding to praise "your wife has a beautiful face". You do the same with me. Even if you see my wife and think it's really ugly, you will call it "your beautiful wife." I don't call this hypocrisy. It's called thoughtfulness. The Japanese have always had this tradition of thoughtfulness.

A still from the movie "Worried Country" (1966).

Best: Exactly. But I'm off topic, for example, this is also the case. I am a foreigner and speak Japanese. As a result, Japanese people often comment: "I speak Japanese better than any Japanese." ”

Mishima: That's so rude.

Best: It's very uncomfortable to be said that. But isn't it the same thing? If everyone sees my wife as ugly, I have to make a polite assessment: "Your wife is really a beauty." "Aren't the two the same thing, what do you think?

Mishima: It can be understood that from a certain point of view, it does feel uncomfortable.

Best: This kind of thing is really unpleasant. In fact, in the end, there is nothing really unbearable in my heart. It's just that if it's true, it's hard to talk about it anymore. I agree, indeed, as she said, a difference in habit.

Mishima: When I think of hypocrisy, I always think of the West and Japan's modernization. And modernization, Christianization, and the Christian church behind it. In addition, Protestantism comes to mind. It has become one of the keynotes of postwar Japan. In a sense, this is influenced by the United States.

Best: It seems to me that it is far from developed.

Mishima: However, the Japanese intellectual class has been completely infiltrated by it.

Best: Especially political.

Mishima: The political dimension has been completely eroded. I was so disgusted with it that I didn't want to see it.

Best: You call the Japanese constitution hypocritical, I wonder if you can explain more about this? After all, there are many people who support a peaceful constitution with a simple and sincere attitude. I think maybe they didn't think so much as they could be seen as hypocritical, maybe they didn't think so deeply. It's just that instead of dying, I simply hope to live longer. Is the truth really to the point of being called hypocrisy? ...... Or are you referring to the intellectual class just mentioned?

Mishima: I'm talking about the intellectual class. Why is the Constitution hypocritical? I have written in other newspapers, such as the Black Market Food Suppression Act, which appeared after the war. If this law is followed, people will die. A judge who tried his best to comply with the law died of malnutrition. It was later widely reported in the newspapers, leading to the overturning of the law throughout Japan. People come out of the black market carrying sweet potatoes to survive. In order to survive, it must be overthrown.

The question of law and death has been the greatest problem facing mankind since Socrates. In my opinion, the most essential problem of human society is to choose to abide by the law or die. Looking at it this way, if the original Japanese constitution is taken literally, the Japanese people will only have a dead end. In other words, the Self-Defense Forces cannot exist, and perhaps the police cannot exist either. The whole of Japan is a completely naked country, and everything you need cannot be had. Therefore, everything that Japan is doing now is unconstitutional. That's how I think. Although people recognize the existence of the Constitution in reality, what both the government and the people do is contrary to the Constitution. Therefore, in order to survive, we betrayed the Constitution.

In this way, like the Black Market Food Prohibition Law, the law is eroding ethics step by step. We didn't want to die, so we looked for a way to escape in desperation. This is contrary to the death of Socrates. The judge, who was willing to die like Socrates, was a great man. But it can't be for everyone. We need to live. So I think for today's constitution, the doctrine of legitimate defense holds. In order not to die, they played word games on the current constitution, had self-defense forces, and through a series of means, they barely made today's Japan exist, and Japan was shaped as a result. But I don't think that's going to work, and human morality will be eroded.

As an ideal, I express my admiration. Nor am I completely negating Article 9 of the Constitution. I think it's great that humanity doesn't go to war, and it's great to keep the peace. But the second item is not feasible. This second is imposed on the coercion of the United States occupying forces. This rule was reversed by Japan's so-called "experts", and the existence of the Self-Defense Forces was recognized. In this way, the Japanese have been fooling for more than 20 years, and it is estimated that after that, the LDP government intends to continue to fool them.

I was so disgusted by that. I can't stand the self-deception. That's all I really loathe. This approach is to try to muddle through the most fundamental point of ethics and morality. People do this even if the law says so. For example, while shouting resolutely against monopoly capitalism, opposing this and that, while listening to Sony tape recorders. This is how people are eroded little by little. Everyone is happy in their hearts, they can eat, live, and have a salary, so they can make do with it. I hate that mentality. Is it really enough to live when there is a reason for pleasure, when pleasure is justified?

BEST: What do you mean by justification?

Mishima: The law is killing the Japanese. If you can live in this way, isn't it justified?

A still from the movie "The Biography of Yukio Mishima" (1985).

This article is exclusive. Original author: Yukio Mishima; Excerpts: Shen Lu; Editor: Zhang Ting; Proofreader: Lucie. Welcome to Moments.