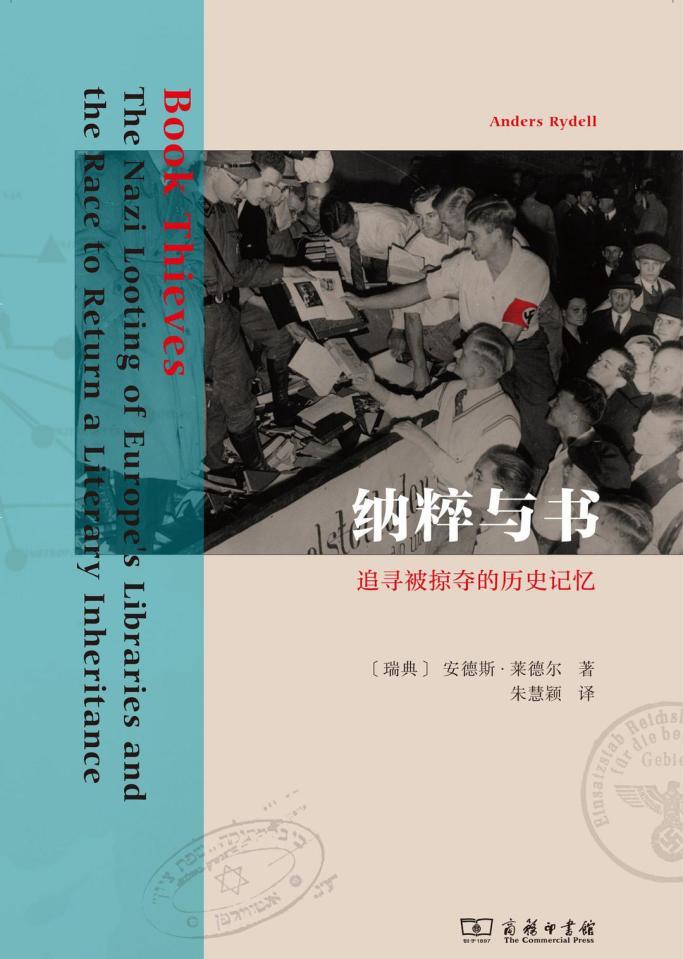

Nazis and Books: The Search for Plundered Historical Memories, by Anders Leder [Sweden], translated by Zhu Huiying, The Commercial Press, August 2021 edition, 328 pp. 66.00 yuan

Compared to the books I've read before on the theme of Nazis and books, The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe's Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance by The Swedish journalist and nonfiction writer Anders Rydell. 2015; Translated by Zhu Huiying, The Commercial Press, August 2021) has two new narrative perspectives, one is to focus on the purpose, process and details of the Nazi Empire's plundering of books in Europe, and the same acts of looting books that still existed after the war and the difficulty of returning to the Owner; the other is to analyze the importance and use of books by the Nazis, and to expose the evil nature of Nazi fascism from the purposeful looting and use of books by the Nazi Empire. The book's original title, literally translated as "Book Thieves: The Nazis' Plunder of European Libraries and the Return of Book Heritage," is a straightforward account of the book's main content. The 2018 Taiwanese translation is "Book Thieves: Cultural Looting and Memory Destruction of Constructing the Myth of Rulers" (translated by Wang Yue, published by Marco Polo Culture); and now the title of the commercial version does not directly translate "stealing books", and "Nazis and Books" seems to be more able to summarize the core content of the book. However, the subtitles of the two Chinese translations are a little far from the content of the book that the subtitle of the original book is intended to express, and perhaps the translator prefers to express the deep meaning in the narrative content.

The above two narrative perspectives can extend and excavate a series of important issues in the study of the history of the Nazi Empire, such as the history of books, reading, and spiritual culture in Europe before and after World War II from the fate of books, as well as how the rise of the Nazi Empire and cultural atrocities changed and destroyed this cultural map; from the use of books looted by the Nazis, it is directly related to the study of the ideology, education, and scholarship of the Nazi Empire, and it is an important issue in the study of knowledge production and ideological warfare in Nazi politics. These issues are not new in the study of Nazi history, but they may not be much in the context of looting books. Although the topic of "Nazis and the Book" is only a small topic in the study of the history of the Nazi Empire, digging deeper into it can still find many new problems worth studying. From this point of view, this popular reading for the public, I think it has its important academic value.

The book begins and ends with the same thing. The author traveled to Birmingham in 2015 with a small book with an olive green cover in his backpack. After traveling through more than seventy years, the book will return to Els, the granddaughter of its former owner, Richard Kobrak. The title page was plastered with a library ticket, and the title page read Kobrak's name. At the end of 1944, Kobrak was put on a train to Auschwitz with his wife and then driven into the gas chambers. The only thing that Richard Koblak has left in the world is this little book. The cover is vaguely gilded with a pattern: a sickle placed in front of a bouquet of wheat, titled Recht, Staat und Gesellschaft, by the conservative politician Georg von Hertling. The author knows that the book is not particularly valuable today, and that it may well sell for a few euros in the old bookstores of Berlin; but he knows even more that it is worth tens of thousands of dollars, because it is too precious and too important for the descendants of its owner. In addition, it is one of millions of books still waiting to be sorted, waiting to be found by the former owner. More than half a century has passed, and they have been forgotten or marked pages torn off by those who know their origins, personal gifts have been crossed out, library catalogues have been forged, and "gifts" from the Gestapo or the Nazi Party have been written in the catalogues as coming from anonymous donors.

This is a sad history of book gathering and dispersion, and what is even more sad is the tragic fate of the original book owner, such as richard Kobrak, the owner of this small book. His granddaughter Els told the author that his grandfather, a civil servant, was persecuted by the Nazis because he was of Jewish descent, and that although he had always been wise and concerned about political information, he thought Hitler's rule would not last long when the deadly lasso was slowly tightening — which the author said was very suitable for those who chose to stay in Germany at the time. Finally, after waking up and trying his best to send his children abroad, he could no longer leave. The little book was no doubt snatched together when the family was looted by the Nazis, and later flowed to the Berlin Library, which has hundreds of thousands of such books.

The author's reason for writing this book began with a focus on the theft and looting of European art by the Nazis. This practice, as well as the postwar process of restitution, has been in the spotlight for decades, and the author published In 2013, The Predators – How the Nazis Stole European Art Gems. In the process he discovered that in addition to works of art there were books, but the latter was easily forgotten. The reason is simple, both because of the prices of the works of art that were originally in the hands of museums and collectors, the workings of the art market and the interest of the media, but also because of the daunting task of sorting out the origin of the millions of looted books and finding their original owners.

What was the difference between looting art and looting books for the Nazis? The former was mainly distributed to Nazi leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering, who intended to show in art that the world they ruled was beautiful and greedy; the latter was important in the service of ideological wars of thought, with the aim of ideologically defeating and destroying the "enemies of the Empire" and constructing the legitimacy of the German Empire and the myth of its glory and eternal invincibility. Many of the owners of the looted books were ideological enemies — Jews, Communists, Masonics, Catholics, critics of the regime, Slavs, etc. The looting was carried out mainly under the leadership of SS leader Heinrich Himmler and Nazi Party chief theorist Alfred Rosenberg. After the Nazis came to power, an organized and purposeful act of plundering books took place in European countries along with nazi anti-Semitic atrocities at home and foreign annexations and acts of aggression, from the Atlantic coast to the Black Sea, from Amsterdam, Paris, Rome, Thessaloniki to Vilnius, from public libraries to private residences. Due to the long duration of the process and the complexity of the situation involving States, institutions, groups and individuals, the truth of the destruction, dispersal and eventual whereabouts of books is difficult to ascertain to this day, and the determination of a large proportion of crimes is still pending.

Following the trail of book robbers, Leder traveled thousands of miles across Europe, searching for libraries, archives and other institutions and insiders everywhere, in order to understand and recreate the history of the catastrophe of this forgotten culture. "I wandered from the libraries of exile scattered in Paris to Rome, looking for ancient Jewish libraries that date back to the beginning of the century and no longer exist. Then I searched for the secrets of Freemasonry in The Hague and returned to Thessaloniki in search of fragments of an extinct civilization. I also came from the Spanish Jewish Library in Amsterdam to the Jewish Library in Vilnius. In these places, people and their books were torn apart, sometimes destroyed: traces were everywhere, though often only scales and half claws remained. In addition to revealing the truth of this history, the author records the institutions and individuals who are still working to organize and return those books, and also expresses the common sentiment of book lovers: "Even if it is a book, it must be returned to those who have lost too much." "[The Chicago Tribune]) more importantly reminds readers that the Nazi dictator's looting of books is ultimately about destroying real memories of history and culture." When I wrote this book, I realized that these memories were at the heart, and that they were the reason books were looted. Robbing people of their words and accounts is a way of imprisoning them. (ibid.)

Well, "Say, memory!" "(Nabokov) Although many memories are told, one may find that there is nothing new under the sun.

The Nazi book burnings on the night of May 10, 1933, in Berlin's Theatererplein, became the strongest symbol and metaphor of exterminated culture in modern history, and have been mentioned in countless works on the Nazi Reich. Many researchers have also published monographs on the book burning, such as the journalist Die verbrannten Dichter (1977) by journalist Jürgen Zelke, and the book of book burning by literary critic and biographer Volker Weidmann (translated by Song Shuming, CITIC Publishing House, June 2017). In the book, Leder talks about what happened before and after the book burning, and on the other hand, emphasizes that the symbolic event of book burning often obscures and blurs people's understanding of the relationship between the Nazis and books.

Before 1933, the Nazis' persecution of intellectual and cultural activities and writers and intellectuals had begun. "By choice, some writers became the subject of surveillance by stormtroopers, who stood outside their homes, and wherever they went, these people followed." (p. 2) The National Observer published a manifesto signed by forty-two German professors declaring that German literature should guard against "cultural Bolshevism," and later published a blacklist of writers to be banned when the Nazis came to power. In February 1933, President Hindenburg signed the "Protection of the People and the Nation" decree restricting the freedom of the press. The German University Students' Union launched a book burning campaign on May 10, but as early as 1922, hundreds of students burned books at Berlin's Tempelhof Airport. Students first cleaned up their own personal collections, then extended to public libraries and local bookstores, and many times university provosts, faculty, and students worked to clean up school libraries. Between the Great Depression and inflation between the two world wars, fewer and fewer Germans could afford to buy books, and traditional libraries could not meet people's needs, so more than fifteen thousand small lending libraries appeared in Germany. These libraries buy bestsellers in large quantities and offer inexpensive lending services that may seem surprising even today. But these "people's libraries" are more likely to fall into the hands of students. (p. 5) About 1 million books belonging to these libraries were looted.

In 1932, many Jews and Communists began to dispose of their personal collections, destroying photographs, address books, letters, and diaries. There are thousands of examples of people burning books in their own stoves, fireplaces or backyards; later many people, in order to save time and fear trouble, simply throw their books into the woods, rivers or streets where pedestrians are extinct, and some anonymously mail books to virtual places. (p. 6) However, the perception of the act of book burning by many well-known German intellectuals is harrowing, and they should "believe that the burning of books expresses the revolutionary fervor of spring, from which the new regime will sooner or later 'grow'". (11 pages)

On the other hand, "even the Nazis recognized that if anything was more powerful than simply destroying the word, it was to possess and control it." In the mid-1930s, the Nazi-controlled book club Buchergilde Gutenberg had 333,000 members, and the Nazi regime was able to efficiently deliver works from Goethe and Schiller to statists and Nazis to millions of readers. "It has stimulated literary and political enthusiasm unprecedented in German history, and presumably unprecedented, and it awards more than 55 literary awards each year." (p. 8) In the 1930s, about 20,000 new works were published in Germany every year, and books that the Nazi Propaganda Department considered "educational for the people" were published in large numbers. Hitler's Mein Kampf was printed in 1933 alone in 850,000 copies, and more than six million copies were sold during the Nazi Reich. (p. 9) It is not surprising, though, that in the past newlyweds received the Bible as a gift, and after the Nazis came to power, they probably received Mein Kampf.

Tens of thousands of books were burned in the square in May, but many more were sent to satrooper headquarters. The author argues, "To be precise, the Nazis were neither 'cultural barbarians' nor anti-intellectuals as they were perceived. Instead, they seek to create a new kind of intellectual, who lives not in liberal or humanitarian values, but in his country and race. The Nazis were not opposed to professors, researchers, writers and librarians, but wanted to absorb them into an army of fighters on the ideological and ideological fronts, declaring war on the enemies of Germany and National Socialism with their pens, ideas and writings." Books, too, became weapons of the Nazi Party, which "confronted the enemy with his own collections of books, archives, history, heritage, and memories." It is this idea that the right to write their history has led to the greatest book theft tragedy in the history of the world." (p. 13) Leder sums it up well: "The Nazi Party waged two kinds of warfare: the first was a conventional one in which the army confronted the enemy in a military conflict; the second was a war against an ideologically hostile force. ...... The war of ideology is fought not only by the use of terror, but also by the war of ideas, memories and ideas, a war to defend and legitimize the national socialist worldview. (pp. 94-95) In this war, books are an extremely important weapon.

The Bavarian National Library has a unique collection, as some of the first books stolen by the Nazis were stored here, because it was Munich, the birthplace of National Socialism. Leder saw a book stamped with the seal "Political Library, Bavarian State Political Police", and he felt that he saw the source of the Nazi plunder of books, "We can think of these books as archaeological remnants of the book-snatching program, which covers the ideological wars organized by research institutions, elite schools, and secret police organizations." ...... These seals represent the Nazi regime's earliest attempts to develop ideological programs and acquire knowledge. This plan proposes not only the study of the enemy, but also the construction of a completely new cultural research and education based on ideology in the Third Reich. ...... This approach is based on a totalitarian ideology that wants to control the lives of its citizens in all its aspects. The same totalitarian thinking is applied to science, trying to redefine every field of science. Everything must be National Socialist.... (p. 56)

But it should be admitted that the Nazis were very serious about the management and use of books. Leder notes that a work of anthropological research on the health of indigenous children also has the seal of the Bavarian political police, "which shows that the ambitions of the security police are not limited to the study of communists and subversive political groups." In fact, the political police were an early part of the most vigorously enforced totalitarian philosophy within the Third Reich, called the SS or SS for short. (p. 57) Since the Nazis came to power, the federal secret police and security services have been keeping a close eye on all aspects of the book market, from literary criticism, libraries, book publishing, and book imports, to the arrest and harassment of authors, booksellers, editors, and publishers. In 1936, the "Library for the Study of Heterogeneous Political Literature" was formally established in Berlin, and Himmler ordered all secret police departments in Germany to check the list of confiscated books to be sent here immediately, and in May of the same year, the library's collection had reached 500,000 to 600,000 volumes. (60 p. 60) The library was incorporated into the Second Division of the Central Security Service in 1939 by the Nazi Party's Security Apparatus, and soon after transferred to Division VII, a research department dedicated to "ideological research and evaluation." It was the highest level library within the Nazi Party and reflected the worldview of Himmler and the SS. Leder said the most curious collection here is the occult books, illustrating that mysticism is a serious theme of the SS. Before the SECURITY Service was formed, the SS had a "library of the occult" and specialized research departments, and even kidnapped some Jewish scholars to work here. The author points out that the research carried out by the Imperial Central Security Service was carried out not only to study the enemy in order to defeat them more effectively, but also to infuse this knowledge into the ideological and intellectual development of the SS. "The SS waged a war against Jewish intellectualism, modernism, humanism, democracy, the Enlightenment, Christian values and cosmopolitanism, but it was fought more than arrests, executions and concentration camps. ...... Totalitarian ideologies not only want to control the people, but also try to control their minds. ...... In the shadow of Himmler's library, we should still ponder the question: which is more terrible about the totalitarian regime's destruction of knowledge or its thirst for knowledge? (p. 63)

The problem stems from the changing situation before and after the Nazi regime. The Nazi movement originally contained many different ideological tendencies, and different forces and groups often tried to lead the Nazi Party in different political directions. "At the constant core of this chaotic political movement is Hitler himself and the leadership principles that have taken shape in him, the so-called 'Führer Principle'— blind and absolute obedience to the Führer– the most important pillar of Nazi ideology." (p. 67) After Hitler came to power in 1933, new members continued to join the Nazi Party, and how to unify the mind and purify the ranks was a more obvious new challenge. To this end, Hitler put Rosenberg in charge of the spiritual and ideological development and education of the Nazi Party, and established an institution in Berlin collectively known as the "Rosenborg Office". Rosenberg believed that the most important tool for changing people's minds was the educational system, which began in 1933 and gradually implemented the Nazismization of the school system from kindergarten to university. This reform was strongly supported by teachers and students in schools, as the Nazi Party had long attached importance to working among teachers, and as early as 1929 it established the Nazi Teachers' Federation (NSLB). So textbooks had to be rewritten, subjects were to be changed, and teachers had to swear allegiance to the Fuehrer like soldiers. In addition to Mein Kampf's Myths of the Twentieth Century, the school's most important ideological education books, included new subjects such as "Racial Hygiene" in the school curriculum. Rosenberg also commissioned a manual called The Theme of Ideology, which outlined the main foundations of the Nazi worldview and was used in schools throughout the country. "The purpose of this, as Rosenberg put it, was to allow Nazi ideology to permeate every subject, from history to mathematics." Moreover, in this Nazi education system, "not only the teacher had to monitor the student, but the student also monitored the teacher, and the student could report to the Hitler Youth or the Gestapo the teacher who made 'non-German' remarks." (p. 80) In 1937, Hitler approved the establishment of the "German National Socialist Workers' Party Higher School" under the responsibility of Rosenberg, because the training of education under the leadership of the future Nazis could not be handed over to the traditional school system, and Rosenberg hoped that this "most important research, education and teaching center of National Socialism" would become the cornerstone of this ideological cathedral. (83 pages)

The Nazi plundering of books often had a clear purpose and pertinence. In June 1940, the Institute of International Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, became the first victim of Nazi plundering of books in the Netherlands, because Nicolaas Wilhelmus Posthumus, a professor of Dutch economic history, founded the institute in 1935 to oppose the fascism that was ravaging Europe at the time. In the 1930s, a large number of refugees from the Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy poured into Western Europe, which also brought with them many valuable documents and books, and Postems tried his best to collect books and documents related to socialism, trade unions, and the workers' movement, and to create a safe harbor for them, because the Nazis and the Soviets were ruthlessly tracking these books. Thus the archives of Marx and Engels, including the manuscript of the Communist Manifesto, are housed here, with more than five shelves of material, notes, manuscripts, and all-encompassing correspondence between the two men. These archives were smuggled out of the Nazi Reich by the German Social Democrats in 1933 and had to be sold in the face of economic hardship. The most eager buyer at the time, ready to pay the highest price, was the Marnelei Institute of the Cpsu Central Committee in Moscow, but the Social Democrats thought it was humiliating to sell to Stalin, so they were bought by Postems. The professor of economic history was so powerful that his collection included archives of the anarchist Bakunin and the Russian Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks, and his paris office also housed Trotsky's archives donated by Trotsky's son, from which Soviet Agents of the Trotsky (DRU) stole many of Trotsky's documents. Now, the Nazi Rosenberg task force had arrived, and all the books and other archives from the library had been shipped back to Germany, but Mann's archives had been preemptively transported by Postems to his Oxford division.

The Nazi plundering of books in Germany and across Europe was a multi-sectoral and fiercely competitive relationship, and from the perspective of books, it can also reflect the organizational structure within the Nazi Reich and its power struggles. The two biggest competitors in the looting campaign were the Rosenborg Task Force, which fought with the SS and the Seventh Division of the Imperial Central Security Service to gain the power to plunder and distribute a library. Generally speaking, the SS had a strong military and police force and clearly had the upper hand; Although Rosenborg's organization did not have its own army, he also alleviated this imbalance by forging strategic alliances and, above all, with Goering. In order to avoid competition falling into anarchy, the Nazis also had to control it with rules and regulations. Thus the SS and the Rosenberg Office would also reach a compromise on the distribution of books, with Himmler all materials that would help the Security Service and the Gestapo deal with the enemies of the state, and books and archives valuable to the study of ideology to Rosenberg. But in reality things will never be so simple. (pp. 97-98)

Finally, back to the difficulty of returning these looted books.

At that time, the Prussian State Library (now known as the Berlin State Library) had a large collection of Nazi looted books. In 2006, a student pointed out in his master's thesis that the library had nearly 20,000 stolen books, and this history was only revealed. The library was also tasked with distributing books looted from the Nazis, and from looting to distribution, more organizations, institutions, and government departments competed to get involved, and at the end of the war, the library was looted by soviet troops, and it is estimated that two million books were shipped to the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, East Germany sold a large number of books to Nishiho for economic reasons, which were distributed to the university libraries in West Germany. (p. 28) It is now too difficult to trace the diaspora of these books.

In the Central and Local Library of Berlin, an account book was discovered in 2005 with about two thousand books registered, which was confirmed to be part of a collection looted during the war. Even more surprising was the fact that the last book in the account book was catalogued on April 20, 1945, when Soviet artillery fire bombarded the center of Berlin and the troops began to attack the city, when a librarian was sitting in the basement cataloging the stolen books. In 2010 the museum began systematically surveying its collection of books, with the most difficult of which was to find their owners or descendants so that they could be returned. In 2012, they developed a search database that fed in information, signatures, and marker images left by the owner of the looted book to "let those descendants come to us." This method has worked, and there are currently fifteen thousand books in this database, but from 2009 to 2014 only about 500 books were returned to their original owners, and the library may have 250,000 stolen books. With the exception of the Berlin Central and Local Library, only about twenty of the thousands of libraries in Germany are actively verifying their collections. (24 pages)

The seals of the books that were torn off on the title pages of those books, the signatures of the original owners that were erased, stolen, and obliterated are countless historical memories that have been erased, stolen, and obliterated. The author concludes the book with a quote from Aunt Ayres: "Tomorrow is Easter, and all we can do is never give up hope." ”