Wine is a magical drink that originated in prehistoric times and has played an extraordinary and important role in the social history of all peoples around the world since ancient times. On the issue of the origin of wine, as far as China is concerned, the academic community has conducted more in-depth research in the past century, and some important scholars such as Ling Chunsheng, Li Yangsong, Bao Qi'an, etc. have published a number of achievements, especially in recent years, scientific and technological archaeologists represented by Liu Li have made great breakthroughs. However, most of the above studies focus on the situation of the Yellow River Basin in the north, and also involve the Yangtze River Basin, while there are very few studies on the Lingnan region. At present, no scholar has yet taken scientific and technological measures to detect the archaeological remains related to the origin of winemaking in Lingnan, and this paper intends to synthesize archaeological data, ethnological materials and documentary records, starting from several aspects such as resource endowments, ceramic wine vessels and agricultural origins, to explore the relevant issues related to the origin of winemaking in the prehistoric period of Lingnan.

First, the background and resource endowments of the origin of winemaking in the prehistoric period of Lingnan region

Exactly how early the history of human winemaking is not clear, but it is certainly very early. In 2014, the research team of American biologist Matthew Carrigan published a genetic study and found that the "ethanol dehydrogenase 4" of the ancestors of mankind 10 million years ago had a monomer genetic mutation, which enhanced the human ethanol metabolism ability, allowing them to rely on highly fermented fruits on the ground to feed them when food was scarce. This genetic mutation should be the result of adaptation, indicating that alcohol-containing diets have accompanied human past and present lives, and that alcohol has never been available or lacking in human recipes. As for the active brewing of human beings, it is possible that the Paleolithic era already existed. Humans collect ripe wild fruits, place them in stone depressions, and naturally ferment them into wine, similar to the legendary "ape wine" made by apes. The "History of Chinese Science and Technology And Chemistry Volume" believes that winemaking already had a certain foundation in the Paleolithic Age, and it was in the Neolithic Age. Extracting sugar from natural or renewable sources and fermenting into wine, this early winemaking technique was not complicated and once had multiple independent origins around the world. According to the ethnographic records of the Western colonial era, only the very minorities in the world – such as the Eskimos and the Indians living on tierra del Fuego in southern South America and the indigenous peoples of the Australian continent – have not invented and tried alcohol, and other peoples have enjoyed the spiritual comfort and medical benefits of alcohol. In addition to the lack of monosaccharide resources in the north and south poles of the world, temperate and tropical regions rich in honey, sugar-rich fruits and other plants have rich winemaking resources, which are enough for ancient humans to discover or invent this magical drink in the long years. At present, in the northern region of China, the remains of ancient wine from the prehistoric period have been clearly found, and the main evidence comes from the testing work of two scientific and technological archaeological teams. The leaders of both teams are from the United States, Professor Patrick E. McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania and Professor Liu Li of Stanford University. In cooperation with Chinese scholars, McGovern has examined specimens from the Jiahu ruins in Wuyang City, Henan Province, and the ruins of two towns in Rizhao City, Shandong Province, which is the earliest activity of Chinese archaeology to use scientific and technological means to conduct ancient wine research. McGovern's analysis of specimens of pottery residues from the JiaHu site suggests that some of The Lake's small-mouth amphora pottery was once used to process, store, and hold a fermented mixed beverage made of rice, honey, and fruit (grapes or hawthorns, possibly longan or dogwood). Although direct chemical evidence of alcohol cannot be found due to the volatile nature of alcohol, it is clear that this is a liquor mainly brewed with rice. JiaHu ruins belong to the PeiLigang cultural period, dating back about 9,000 years, Jiahu ancient wine in the world also belongs to one of the earliest ancient wine remains. Multiple chemical analyses by McGovern's team of longshan culture pottery specimens from the site of two towns in Rizhao, Shandong Province, showed that the wine people drank at that time was a mixed fermented beverage that contained rice, honey and fruit, and may have been added with ingredients such as barley and plant resin (or herbs). Liu Li's team made a residue analysis of Yangshao culture pottery excavated from many sites in the middle reaches of the Yellow River, and found that a grain sprout wine was popular at that time, the main ingredient was a combination of millet or rice, and other ingredients included coix, barley, wheat tribe, chestnut root and mustard, etc., in addition to additional plant raw materials such as root. The reason why winemaking has already occurred in the early and middle Neolithic period in northern China is based on the needs of life and culture, and at the same time has corresponding resource conditions. And this kind of survival needs and resource endowments also exist in the Lingnan region, or even more superior. It is human nature to like fine wine and food, and the anesthesia and stimulation caused by alcohol to the central nervous system can bring pleasure to people, which is the basis of wine throughout human history. The anesthetic effect of alcohol later took on social significance, such as for social and ceremonial purposes, and religious activities were inseparable from alcohol. In alpine areas, wine can also drive away the cold. Grain sprouts with dregs, also known as mash, can also fill the hunger. These practical and non-practical functions are common all over the world, and the same is true in the Lingnan region. Contemporary Chinese wine culture is very prosperous, and the Lingnan region is no exception. Lingnan's wine culture originated from ancient times and can be described as having a long history. Today, the Zhuang, Dong, Miao, and Yao ethnic groups all maintain their own unique wine cultures, and wine customs and wine ceremonies are different. Especially in the southwest ethnic areas, there are still special customs like "sacking wine", which has been handed down from ancient times. The rice wine commonly brewed in the southern ethnic areas is completely different from distilled wine, and has a very long history, basically continuing the brewing method of ancient gu bud wine. Li Fuqiang and Bai Yaotian's "History of zhuang social life" sorts out the situation of liquor in Zhuang areas from the Han Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty based on historical books such as "Lingwai Dai Answer", "Guihai Yu Hengzhi", and "Sui Shu Geographical History". For example, the Southern Song Dynasty Fan Chengda's "Guihai Yu Hengzhi Zhijiu" said, "Old wine, made of wheat qu, sealed and hidden, can be several years." This method of winemaking is similar to that of koji wine in the north. The Qing Dynasty Qian Yuanchang's "Records of the Barbarians of Western Guangdong" records that the Guangxi area "makes wine, made of rice and grass, and has a very sweet taste." "This is the grass koji wine unique to the south, which has an extremely long history, dating back to prehistoric times. The history of winemaking in the Lingnan region, like in the northern region, can certainly be traced back to prehistory. The earliest evidence of winemaking in the north comes from the Jiahu site, 9,000 years ago. The earliest appearance of winemaking should have been earlier than this era. Because jiahu wine is relatively mature, it is not the earliest type of wine. It is generally believed that mainland liquor can be divided into three stages of development: naturally fermented fruit wine, brewed grain wine and distilled spirits. Fruit wine is not very developed in the mainland, but there are also records in the literature, such as the Tang Dynasty Su Jing's "New Cultivation of Materia Medica" in the "wine" word download has "to make wine liquor to qu, and pu peach, honey do not use song". The Southern Song Dynasty carefully recorded in the "Pear Wine" article of the "Decoction Miscellaneous Knowledge" that Yamanashi had been stored as wine for a long time. Jiahu's wine is mainly rice, with fruits and honey, which already belongs to grain wine, the so-called "li". Before the appearance of Jahu wine, there should be a stage of natural fermentation of cider. That is to say, the history of the emergence of continental wine should be in the early Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. The emergence of wine should be closely related to the overall transformation of human lifestyle after the Holocene, and it is also an important part of Neolithic. The origin and development of wine is closely related to a series of problems such as the increase in the degree of settlement, the expansion of recipes, low-level food production, primitive religion, and social complexity. Whether it is the natural resources needed to make cider or grain bud wine, there is a rich presence in the prehistoric Lingnan region. From the perspective of prehistoric climate and vegetation distribution area, the north mostly belongs to the warm temperate deciduous broad-leaved forest area, and the lingnan mostly belongs to the subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest area and the transitional tropical forest belt. Lingnan is richer in animal and plant species, and the carbohydrate produced per square kilometer throughout the year far exceeds that of the north, which is also an important reason why Lingnan has maintained an economic form of fishing, hunting and gathering for a long time in the prehistoric period. At present, a number of important sites have been studied in plant archaeology, and many of the plant resources used can be used for winemaking. The jade toad rock site in Daoxian County, Hunan Province, dating from 12,000-10,000 years ago, has found a small amount of ancient cultivated rice in the strata. Rice has a strong saccharification power and is one of the most commonly used wine grains. A small number of semi-domesticated rice grains have also been found at the Yingde Niulan Cave site in Guangdong, dating from about 12,000-8,000 years ago. At the same time, the plant archaeology of the Guilin Koshiki Rock site was more fully done, and no trace of rice was found here, but there were many other plants. The edible plant species identified by flotation include pecans, plums, mountain yellow peel, phyllonorycters, water owls, mountain grapes, pu tree seeds and tubers of the potato family, etc., and according to the results of the above-mentioned work by McGovern and Liu Li's team, these plants can be used for winemaking. Later, the more well-studied sites of the middle Neolithic period in Lingnan are the Dingsi Mountain in Yongning, Guangxi. Silica identified the presence of plant remains of the family Poaceae, Palmaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Cherimoaceae, etc., and these plant species include many edible fruits, seeds or rhizomes, such as the palm family's prickly sunflower, betel nut, gourd fruit, gourd, oil pomace fruit of the Cucurbitaceae family, stone dense, melon and so on. These plant resources can be fed and can also be used to brew fermented beverages. The most well-studied late Neolithic excavation and research in the Lingnan region is the Qujiang Shixia site in Guangdong, where a relatively large number of rice remains have been found, as well as the remains of fruits such as dates. Mature rice cultivation in the late Neolithic period has been introduced from the Yangtze River Basin to Lingnan, and many sites have unearthed more rice remains, such as the Guangxi Resources Xiaojin Site and the Guangdong Qujiang Shixia Site. During this period, winemaking was already common in the Yangtze River Basin and the Yellow River Basin, as can be seen from the large number of wine vessels excavated from the Dawenkou culture, Longshan culture, Songze culture and Liangzhu culture. As an integral part of the rice farming culture, with the migration of ethnic groups, the winemaking process should also be introduced to the Lingnan region. The rise of rice cultivation in Lingnan provided a new material basis for the continuation and development of early prehistoric wine culture. If it is said that in the early and middle neolithic period, the winemaking in the Lingnan region mainly used natural resources, then from the late Neolithic period, the winemaking in the Lingnan region began to use natural resources. However, the use of fruits, rice and tubers should be consistent. From the background of the entire era, there is no reason why Lingnan in the prehistoric period did not lack the discovery and invention of alcoholic fermented beverages like other parts of the world. There is both a motivation for winemaking and a very sufficient resource endowment. Archaeological discoveries, documentary records, and analogies to ethnological materials all prove that this is a reasonable extrapolation.

2. Ceramic wine vessels from the prehistoric period of the Lingnan region

The above speculation about the existence of winemaking activities in the Prehistoric Lingnan region can be found in archaeological materials, the most important of which should be pottery. The containers used in early human winemaking should include a variety of materials, such as bamboo, gourd, pumpkin, animal leather, animal stomach bags, pottery and stone tools, etc., but organic matter utensils are difficult to preserve, the number of stone containers is very small, and the relics that can be seen today are mainly pottery. Then, we can identify artifacts with similar functions from archaeological findings based on existing research results in archaeology and ethnology.

The most meaningful thing in studying the winemaking of the prehistoric period is the fermented grain wine represented by gu bud wine, which is called "yellow wine" in the traditional Chinese wine division, which is the most important category. Cider was supposed to have been there before that, but it has not been very developed. And from the principle of brewing process, the two have similarities, both are saccharification, wine, so the container used for fermentation is also very close. From the functional division, the wine vessel should include three different stages, namely the wine vessel, the wine reservoir and the drinking vessel, the most important of which is the wine vessel.

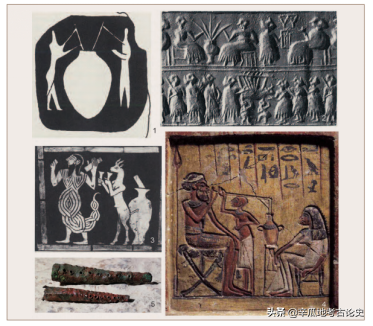

The most common wine-making vessels are small-mouthed, bulging-bottomed or pointed-bottomed pottery. The small opening reduces evaporation, facilitates sealing, prevents rancidity, increases capacity in the drum belly, and facilitates sedimentation of dregs at the round or culet bottom. Most of the original winemaking vessels around the world are of this shape. The use of small pointed bottom bottles can be seen in ancient Egyptian murals and On sumerian seals of the Two Rivers Valley, while clay tablets record grains (barley and wheat) brewing grains, which date back 6,000 years (Fig. 1). Africa has a tradition for thousands of years to use pottery to brew and drink grain bud wine, mostly in large drum-belly circular pots, which can be observed in Sahara petroglyphs dating back to 5,000 years ago.

Figure 1 Small-mouthed culet-bottomed wine vessels in the Two Rivers Basin and Egypt 1.Images of drinking alcohol using small-mouthed cuspid-bottom bottles depicted on the imprints of the Two Rivers Basin, unearthed in Tepe Gawra (about 4000BC) in northern Iraq 2. Feast and drinking scenes on Sumerian imprints unearthed from tombs of your early dynasties, showing two people drinking from small pointed bottom bottles using straws (about 2600-2350BC); 3. Drinking scenes depicted on burial items excavated from your dynasty tombs (about 2650-2550BC); 4. Pictures of drinking with straws on stone tablets of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt; 5. Copper straw heads excavated from the late Bronze Age in Syria (about 1300-1150BC).

Liu Li believes that the main function of the emergence of early Chinese pottery is to cook porridge or winemaking, especially the small-mouth drum belly round bottom jar or pointed bottom bottle, which is mainly a wine making vessel, which has the function of storing wine and drinking alcohol. She systematically combed through the small-mouth drum belly clay pots excavated from the main sites of the early and middle Neolithic cultures in the Yellow River Basin and the Yangtze River Basin, and believed that they may be mainly wine vessels. These sites include Dadiwan, Baijia Village, Magnetic Mountain, Jiahu Lake, Houli, Pengtou Mountain, Shangshan Mountain, Xiaohuangshan Mountain, and Cross-Lake Bridge, ranging from 9,000 to 7,000 years ago (Figure 2). Liu Li's research does not include the Lingnan region, in fact, the prehistoric culture of the Lingnan region also contains a large number of such pottery, which we will sort out below.

Figure 2 Small-mouth drum belly pot excavated from Neolithic sites in the Yellow River Basin and Yangtze River Basin 1.Dadiwan Phase I; 2.GuanTaoyuan Phase II; 3.Baijia; 4.Houli; 5.Jia Lake; 6.Cishan Mountain; 7.Pengtou Mountain; 8.Cross-lake Bridge; 9.Xiaohuangshan; 10.Shangshan

Of all these pottery, the most representative and deeply studied is the small-mouth pointed bottom bottle of Yangshao culture. Liu Li tested specimens unearthed at multiple sites and proved that it was a vessel used to brew and drink grain bud wine, which had the same function as similar pottery in Egypt and the Two Rivers Valley. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 Wine vessel of Yangshao culture - small-mouth pointed bottom bottle 1.Residue of the tip bottom bottle mouth excavated from the Banpo site; 2. Residue of the tip bottom bottle mouth of Xi'an Mijiaya; 3-4.Residue and vertical scratches on the inner wall of the pointed bottom bottle mouth of the Yangshao culture in Luoyang Zhuge Reservoir; 5. The late Yangshao horn mouth pointed bottom bottle excavated from Dadi Bay

Of course, with the development of winemaking technology, ceramic winemaking vessels are not limited to small-mouth drum belly round bottom jars or small-mouth pointed bottom bottles. Vinificationist Bao Qi'an proposed that from the Yangshao culture to the Dawenkou culture and the Liangzhu culture period, the winemaking vessel gradually changed from a small-mouth pointed bottom bottle to a large-mouth pointed bottom urn, which not only shows that the amount of wine is increasing, but also explains the progress of winemaking technology, that is, the transformation from gu bud wine to koji wine, the emergence of steamed rice koji wine in the Dawenkou period is a major progress in the history of winemaking, the pottery and pottery in the same period are warm wine vessels, and the high-handled cup is a typical drinking vessel. (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Various types of wine vessels of Dawenkou culture 1, 2. Faience pot 3.Faience pot

Zhang Xiaofan once systematically combed the wine vessels of Songze culture. According to the basic process of winemaking and the basic function of wine vessels, he classified the ceramic wine vessels of Songze culture into three categories. The first type is wine-making vessels, that is, the utensils used for winemaking, including the koshiki, potted, large-mouth and wine filters, etc.; the second type is the wine storage vessel, which is used to store the filtered wine, mainly the can urn; the third type is the banquet vessel, which is used for sacrifice or feasting activities, including the gourd, the pot, the cup, the special-shaped wine vessel, etc. (Fig. 5) Similar artifacts have also been found in the late Neolithic sites in Lingnan.

Figure 5 Typical wine vessels of Songze culture: pots, cups, cups 1. Pot-type pottery wine vessels; 2. Pot-type pottery wine vessels; 3. Cup-type ceramic wine vessels

In the Longshan period, there were already relatively mature series of wine vessels, and there were wine ceremonies, which constituted one of the core contents of the ancient Chinese ritual system and represented the first appearance of civilization. The process of civilization in the Lingnan Neolithic age is not obvious, and there are no series of wine vessels and wine ceremonies similar to those of the Longshan culture. In addition to archaeological data, there are many ethnological sources that can also be used as references. A number of scholars have conducted special surveys on the wine culture of the southern ethnic regions, from which the general form of winemaking pottery can be observed. Li Yangsong did a meticulous investigation of the Wa pottery making in Yunnan, and found that most of the Wa pottery is a small-mouth drum belly circle bottom jar, which has the function of both a cooker and a wine vessel; there are a small number of pointed bottom tanks, small mouths and thin necks, and their shape is similar to the small mouth pointed bottom bottle of Yangshao culture, which is generally a wine vessel, which is used to brew water wine. (Figure 6) The shape of the above pottery is mostly determined by function, and it also has a certain relationship with pottery technology. The Qiang people in the Minjiang River Valley in Sichuan make "sack wine", and the fermentation stage is to use a one-person-high belly jar, brew it and then open the altar, and then put it into a small "water jar" to drink. The ethnic minorities in The Western Plains of Vietnam are popular in brewing "sack wine", and the winemaking vessels used are also altars or urns with small mouths and large bellies. In fact, the basic form of pottery for fermenting and brewing rice wine has not changed much in ancient and modern times, and most of today's folk winemaking containers are still such small-mouth drum belly jars.

Figure 6 Yunnan Wa pottery wine altar

From this, we can identify similar artifacts from pottery excavated from prehistoric sites in the Lingnan region. In general, the earliest neolithic pottery in the Lingnan region, such as the jade toad rock pottery and the first phase of the pottery of the Koshiki Rock, the fire temperature is very low, the water absorption rate is too high, rough and fragile, and its function should be used for cooking, or as Liu Li said, for cooking porridge, or as the excavators of koshiki rock believe, it is impossible to be used for brewing. Moreover, the pottery of this period is basically a large open mouth, which is completely different from the small mouth drum belly form required for winemaking. The pottery that really appeared suitable for winemaking was in the second phase of Koshiki Rock, during which there were open mouths, corset necks, shoulders, drum belly, and round bottom pot pottery, with larger shapes, uniform thickness and dense pottery tires. Taking DT4(28):052 as an example, the opening is not large, the neck is tightly bound, the shoulders are slipped, the drum belly, and the pointed circle bottom, and its shape is quite close to the basic structure of the small-mouth pointed bottom bottle in Egypt, the Two Rivers Basin and the Yangshao culture, which is quite consistent with the small-mouth drum belly pot commonly seen in the Early and Middle Neolithic periods in the Yellow River Basin and the Yangtze River Basin. It is also very similar to many pot-shaped clay pots excavated from the JiaHu site for winemaking. This kind of pottery in the second phase of koshiki rock has a tight neck and is not suitable for cooking, and it seems that there is no need to make such a complex structure if it is to store water, and it is very likely that it is a wine vessel. Its age is 10,000-9,000 years ago, which is the period when winemaking activities existed in the northern region represented by the JiaHu site. From the second to fifth phase of koshiki rock, that is, from 10,000-7,000 years ago, the number of small-mouth cobneck bottom tanks has increased, and the fire has become higher and higher. (Figure 7) This type of pottery may have a variety of functions such as cooking and storage, but brewing fermented alcoholic beverages should be one of the more commonly used ones. The study of plant remains at the aforementioned Koshiki rock site also shows that they once used resources that could be used to make wine, including a large number of fruits. If you speculate about the type of winemaking of the Koshikiyan people, they are most likely to brew fruit wine, which is also the most primitive type of wine.

Figure 7 Pottery wine vessels at the Guilin Koshiki rock site: phase 2 to phase 5 (press: the first phase of pottery kettles as non-wine vessels)

The Lingnan region is rich in pottery materials in the middle of the Neolithic period, and the ruins of Dingsi Mountain in Yongning, Guangxi. The prehistoric remains of the site can be divided into 4 periods, dating from 10,000-6,000 years ago. Pottery has been unearthed in these four periods, mainly circular bottom pots and kettles, as well as high-necked pots and hooped foot vessels. The pottery that is most closely related to the brewing activity is the pottery of the fourth period in 6000. The fourth phase unearthed not only the corset neck slip shoulder circle bottom jar, but also, of particular importance, a certain number of corset neck amphora abdominal circle foot clay pots (Figure VIII). This kind of clay pot has been excavated in the middle and late Neolithic sites in the Yellow River Basin and the Yangtze River Basin, and can be seen in the PeiLigang culture, Yangshao culture, Dawenkou culture, Songze culture, Longshan culture and Liangzhu culture, which is generally considered to be a wine container. The pot has a central position in Chinese wine ceremonies, and its position in the Bronze Age wine vessel group is also very respected. The clay pot of the Dingsishan culture may be used for both winemaking and wine, and may also be a water vessel. The fourth phase of the Dingsishan site also unearthed two pottery cups, which are eye-catching (Figure 9). The pottery cup is clay red pottery, open, obliquely straight walled, with a small circle foot at the bottom, and the surface decoration is engraved with scratches, with a caliber of 9 cm and a height of 7.6 cm. The pottery cup can drink water or drink alcohol, but in general, the appearance of the cup is more closely related to drinking. Because people drink more water, bowls and the like are more appropriate, and in fact, the appearance of bowls is much earlier than cups. While wine has a degree, the amount of disposable drinking is much smaller than water, and the emergence of ceramic cups with smaller capacity is likely to be related to the consumption of alcoholic beverages. The small-mouthed neck-necked bottom jar, drum belly pot and pottery cup in the fourth phase of Dingsishan Actually constitute a wine vessel system, representing the three stages of winemaking, wine and drinking, respectively. More importantly, a considerable amount of silica was found in the fourth phase of Dingsishan, and it was basically determined that it was artificially cultivated rice. The wine brewed at this stage is likely to be a grain bud wine with rice as the main ingredient and other raw materials like JiaHu. The emergence of the fourth phase of the Dingsishan complete set of wine vessels is inevitably related to the development of rice cultivation, which is the real beginning of Lingnan Neolithic, if we take the emergence of agriculture as a sign of the Neolithic Era. We'll discuss this below.

Figure 8 Amphorae belly circle foot clay pot excavated from the site of Dingsi Mountain

Fig. 9 Pottery cups (Fig. 3) excavated from the Dingsishan site, as well as clay pots and clay pots

The representative site of the late Neolithic period in the Lingnan region is the Qujiang Stone Gorge in Guangdong. The cultural accumulation is divided into four phases, the second of which is called the Shixia culture. The third period belongs to the Shang Dynasty, and the fourth period has entered the Zhou Dynasty. There are clearly wine vessels in the earliest strata of the site, and the pottery of the Shixia culture in the second phase has formed a mature group of wine vessels. The age of the first period is about 6000-5500 years ago, the pottery is relatively fragmented, the vessel is larger, and the most important pottery related to wine is the excavation of a large number of white pottery cups, in addition to the open neck round bottom kettle, deep belly pot, bag foot vessel and so on. In addition, there are table purses such as perforated circle foot plates and bean plates. The perforated circle foot plate and the white pottery cup made of white pottery are the most distinctive, which should be representatives of the food vessel and the wine vessel respectively, and the production is fine, the grade is high, and it is very ceremonial. The age of the second period is 4000 to 5000 years ago, the remains are very rich, unearthed a large number of clay pots and pot-shaped pots, which are typical wine vessels, other related wine vessels include various types of round bottom pots, urns, manes, etc., there are also many high-handled pottery cups and pottery cups, as well as pottery vessels, forming a relatively complete group of wine vessels (Figure 10). Cookware and eating utensils represented by ding, gui, beans and plates are developed, and there are many jade utensils such as zhen, bi and qi. Most of these artifacts are from tombs, reflecting the funeral significance embodied in the Longshan culture with food utensils and the Liangzhu culture with a series of jades, of which the wine ceremony is an important part. More rice remains have also been unearthed at this stage, indicating that this is an agricultural culture. The wine of this period, like the Yongsan culture, should be a grain bud wine with rice as the main raw material.

Figure 9 Stone Gorge culture wine vessel: urn, pot, cup, and spoon

Summarizing the remains of winemaking pottery from the three stages of the Lingnan Neolithic period above can lead to the following conclusions. In the early Neolithic period of about 10,000 years, there were already winemaking pottery represented by the corset neck drum belly round bottom pot, and the brewing may be mainly fruit wine, and wild rice was also used in some places to make wine; in the middle of the Neolithic Age, with the introduction of rice agriculture in the Yangtze River Basin, the grain bud wine brewing technology developed, and complete sets of pottery wine vessels appeared, including round bottom pots, pots and cups; in the late Neolithic period, a diversified group of pottery wine vessels was produced, and the grain bud wine mainly made and drank rice, and there may be wine ceremonies. It constituted an important part of the ceremonial system of the Yongsan period.

Third, the relationship between winemaking and agricultural origins in the prehistoric period of lingnan

The Neolithic period in the Lingnan region has its own peculiarities. According to the traditional understanding of archaeology, the emergence of pottery and grinding stone tools can be regarded as the beginning of the Neolithic era, and the current identification of the Chinese Neolithic era is basically based on this standard. However, with the progress of archaeology, it was found that the pottery in the Lingnan region appeared too early, and the pottery of Yu toad Rock in Daoxian County, Hunan Province, even reached 18500-17500 years ago, as early as the end of the Pleistocene. With the increase in this situation in East Asia and other parts of the world, the academic community has in fact changed the criteria for determining the Neolithic Era, and now generally regards the emergence of agriculture as a sign of the emergence of the Neolithic Age, according to the Western academic community, the so-called "Neolithic", that is, the era of agricultural economy. In this way, there is a debate about the identification of the Neolithic era in Lingnan. Most scholars still adhere to the original view that the Lingnan Neolithic era began at the beginning of the Holocene 12,000 years ago. Some scholars believe that the Neolithic age in the Lingnan region only began around 6,000 years ago. The reason is that before that, the Lingnan region actually belonged to the fishing and hunting economy, agriculture did not really appear, and the rice farming in the Lingnan region actually spread from the Yangtze River Basin around 6,000 years ago. Guangxi's resources Xiaojin, Shixia culture, and later Guinan Dashi shovel culture, their rice cultivation came from the Yangtze River Basin spread. Even excavators and plant archaeologists at the Dingsishan site believe that the rice cultivation embodied in the fourth phase of rice silica may have come from the Yangtze River Basin.

There are also quite a few scholars who believe that 6,000 years ago, there was a local agricultural economy represented by rice cultivation in the Lingnan region. Qin Naichang has examined from various aspects of linguistics, ethnology and archaeology that the rice cultivation culture in the Zhuang area has a history of more than 9,000 years. The remains of rice grains excavated twice in 1993 and 1995 at the Yutouyan site in Daoxian County, Hunan Province, were identified as ancient cultivated rice, dating back to 10,000 years ago (Figure 11). In 1996, excavations at the site of Niulan Cave in Yingde, Guangdong Province, found a batch of rice phytosilite, non-indica and non-japonica, in the original state of domesticated rice, dating from 12000-8000 years ago, Niulan Cave is considered to be the origin of Lingnan rice culture. The Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology of the Shanghai Academy of Life Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Sciences also did rice genome sequencing, and found that ordinary wild rice in the left and right rivers of Guangxi is related to modern cultivated rice, which is the birthplace of Japonica rice in East Asia. In addition to the above research on rice, some scholars believe that horticultural cultivation existed in Lingnan in the early and middle Neolithic periods, and the main varieties were tuber plants and fruits.

Figure 11 Ancient rice excavated from the Jade Toad Rock Site in Daoxian County, Hunan Province

Of course, after the rise of rice farming in the Lingnan region 6,000 years ago, there is no doubt that winemaking activities have developed accordingly. Earlier, when we inspected the Shixia culture, we obviously saw this point (Figure 12), and the wine vessel and wine ceremony have reached the stage of maturity. Based on our understanding of the production of rice wine with rice and millet as the main raw materials, it is natural that winemaking activities are related to agriculture. The traditional view is also that winemaking is the result of the development of the agricultural economy, and there is a surplus of grain before it begins to brew. The ancients also had this understanding, that is, the "Huainanzi Say Lin Xun" said, "The beauty of Qing'an began with the Qi", believing that the emergence of winemaking originated from agricultural production activities. But in fact, this is a stereotype of agricultural society, there is no necessary connection between winemaking and agriculture, winemaking activities are not completely dependent on agriculture, relying on wild natural resources can make wine, winemaking behavior should be produced before agriculture, agricultural economy to winemaking only brings quality and quantity improvement.

Figure 12 Carbonized rice was excavated from the tomb of the second phase (Shixia culture) of the Shixia Site in Qujiang County, Guangdong Province

So how to understand the so-called primitive agriculture that existed in the Lingnan region before 6,000 years ago, that is, the so-called origin of rice cultivation? The use of "ancient cultivated rice" such as Jade Toad Rock and Niulan Cave as the source of Lingnan rice cultivation may not be in line with historical facts. In fact, the rice in jade toad rock and niulan cave is likely to still be wild rice, but it only represents the collection and utilization of wild resources by ancient humans. There are a variety of possibilities for this exploitation. According to Lü Liedan's research, in the early and middle Neolithic cultures of the Yangtze River Basin and the Lingnan region, the human use of rice subfamily plants includes at least three aspects: the first is to use its seeds as food, such as the residents of the Yangtze River Basin may have this behavior, but still need more information; the second is to use rice husks or rice stalks as raw materials for daily necessities, such as the prehistoric residents of Shangshan, Zhejiang, who used rice husks as pottery and materials, of course, other uses cannot be ruled out; the third is as part of the fuel. This was done by the prehistoric inhabitants of the Lingnan region, who lived 12,000-10,000 years ago, as well as rice authors in the modern Lingnan region. Lü Liedan basically denies that the remains of rice found in the early and middle Neolithic sites are the result of human cultivation, nor does he consider them to be human food. The main reason for this is that the return on harvesting wild rice is low, it is not cost-effective compared to other food sources, and the calories provided are very limited. Her reasoning is based on experiments and has some plausibility, but her use of early rice cultivation in Lingnan may be further supplemented. It is very likely that the stems of the early and middle Neolithic rice in the Lingnan region will be used as fuel, but in addition, there is also a great possibility of collecting rice for winemaking. Although it is not cost-effective to collect wild rice for meals, it is cost-effective if it is used as a brewing fermented beverage or a brewing ingredient. Compared to the important functions provided by alcohol, such as alcohol pleasure, group drinking socialization, and religious etiquette, the effort of collecting labor is well worth it. Moreover, rice may not be the only raw material for winemaking, according to McGovern's research on JiaHu, Liangcheng town and Liu Li's team on Yangshao cultural relics, we know that rice, honey, fruits, tubers and other plants can be put into it, which can make up for the lack of rice quantity. The same is true of winemaking in contemporary southern minority areas, sometimes with as many as a dozen ingredients. Of course, rice should be a core raw material, because among the various raw materials, in addition to fruits, rice has a high saccharification and wineification rate, which is difficult to replace. It is said that rice from this period was used for winemaking, but also for other supporting reasons. We have previously examined the possible pottery wine vessels in the early and middle Neolithic sites in Lingnan, the small-mouth drum belly pot in the second phase of the Koshiki Rock and the various types of circular bottom pots that followed were very similar to the wine vessels in the northern region, although the remains of the jade toad rock and the Niulandong pottery were few, and no similar vessels were found, but the age, latitude, environmental conditions and natural resources of these sites were highly consistent, and it was likely to have the same economic form and lifestyle. The Dingsishan culture obviously exists in the wine vessel, and has formed a series, if the use of rice in the early days of dingsishan, if there is also a use of rice, it should be a very likely choice for winemaking. Worldwide, brewing fermented beverages should have been a common practice in the early and mid-Neolithic periods, as should the Lingnan region of China. There are many raw materials that can be used for sake brewing, and rice is only one of them, and it is not an indispensable one. However, if rice is used for winemaking, people may immediately find the advantage of its high saccharification rate and pay attention to it, which will lead to intensive utilization. This utilization, including source management, low-level food production, and cultivation activities, has led to the domestication of plants. The domestication of many plants in the world has the credit of winemaking. A well-known example is the origin of corn, which may be related to the demand for winemaking. Around 2200 BC, at the site of La Emerenciana on the coast of Ecuador, silica stones with corn were found for the purpose of making corn wine, that is, "chicha", which was the period of origin of corn and had not yet been used as a staple food by humans. The early "origin of rice cultivation" in Lingnan may have been partly driven by winemaking activities, so that the ancients selected wild rice from many natural resources for intensive utilization or even focus on cultivation, making rice stand out among many edible plants. But the driving force of winemaking may still be very limited, and it is impossible to have the core driving force of population pressure or resource pressure like the Yangtze River Basin, which can promote the transformation of social forms into agriculture. The resource-selective pressures of winemaking described here drive the origins of rice crops, and the mechanism of action is similar to that of the competitive feasting theory. In the early 1990s, the Canadian archaeologist Brain D. Hayden proposed the theory that agriculture may have originated in areas with abundant resources and reliable supplies, and that the social structure was relatively complex because of economic affluence, so that some chiefs were able to use labor control to domesticate species that were mainly used for feasting, and these species were either gourmet or wine-making, and agriculture gradually occurred in the process. Based on this theory, Chen Chun analyzed the archaeological remains of rice cultivation in the early and middle Neolithic periods in China, and believed that the origin of early Chinese rice cultivation may be related to feasting, and the use of early rice may be due to the need to make fine wine and delicacies. Ma Liqing and others believe that the same is true of the JiaHu site, the rice agriculture of the Jiahu site is not developed, and the first democracy depends on plant roots, nuts, beans and a large number of fish to feed the belly, and uses the collected fruits, honey, grains and planting a small amount of rice to make wine to satisfy spiritual enjoyment. It is also reasonable to explain the remnants of early rice cultivation in the Lingnan region, perhaps because it was the need to feast under the rich hunter-gatherer economic conditions that promoted the development of rice and horticulture. However, it should be noted that food is not a necessary condition for winemaking, a variety of plant resources can provide raw materials for winemaking, and it is not necessarily obtained through farming, and resources can be obtained through collection and intervention, so the impetus of winemaking activities on agriculture is very limited. Feasting can promote the budding of agriculture, but there are still many variables in whether it can move from bud to development. Judging from the situation in the Lingnan region, the so-called "agricultural origin" of the early Neolithic period is very weak and has not developed, which may be the destination of most of the "agricultural origin" phenomena in the prehistoric period. Rice cultivation in the Late Neolithic Lingnan region has little connection with the early and middle agricultural buds, and should come from the Yangtze River Basin. The introduction of rice farming culture and population in the Yangtze River Basin also brought wine vessels and wine ceremonies, and this wine culture did not have much connection with the wine culture of the early and middle Neolithics in Lingnan, as illustrated by the difference between the first phase (pre-Shixia culture) and the second phase (Shixia culture) of the Shixia site. Winemaking was originally a common phenomenon in prehistoric times and did not need to be explained by cultural communication theory.

IV. Conclusion

Due to the natural evolutionary selection of the human constitution, as well as socio-cultural pressures, alcoholic fermented beverages have almost become a necessity in human diets. In the ethnological material we can also see that even in the face of possible hunger, people still use limited grain to make wine. The human need for alcohol has extreme manifestations in modern society, and the root of this phenomenon comes from the depths of history. It is precisely because fermented beverages are an integral part of dietary activities, almost an unavoidable daily behavior, the requirements for tools, raw materials, the environment are not harsh, and the process is not complicated, so it is universal, and winemaking activities are widely present in all regions and ethnic groups in the world. In the early stages of human history, the popularity of wine may have far exceeded what we know today. The main reason for the lack of awareness of this is the nature of alcohol, which is a volatile substance that is difficult to leave traces directly. Moreover, brewing and drinking as part of the food system are often mixed with other eating activities and are difficult to distinguish. The current research on the wine culture of the prehistoric period in the Chinese archaeological community has made significant progress in northern China, but similar work has not yet been carried out in the southern region. From the discussion in this article, we can know that in the prehistoric Lingnan region, winemaking and drinking activities were also widespread, and the degree of development was no less than that in the north. The presence of pottery wine vessels from the early and middle Neolithic period proves this. Moreover, this kind of winemaking activity occurred long before the rise of rice farming, and the economic basis of the two was different, which was different from the current research results in the northern region. The study of the remains of wine at the sites of Jiahu, Liangcheng and Yangshao culture is all related to the development of rice agriculture, and the early wine relics in the Lingnan region may be more based on the economic basis of collection. The phenomenon of "origin of rice cultivation" in the early days of Lingnan should have a certain relationship with winemaking activities. The need for winemaking has facilitated the use of rice, which has led to the domestication of rice. However, this need has a limited impetus for the origin of rice cultivation and is not enough to give rise to a mature rice farming system. With the evolution of culture, the faint signs of "agricultural origin" in the early lingnan gradually disappeared into the long river of history.