Li Gongming

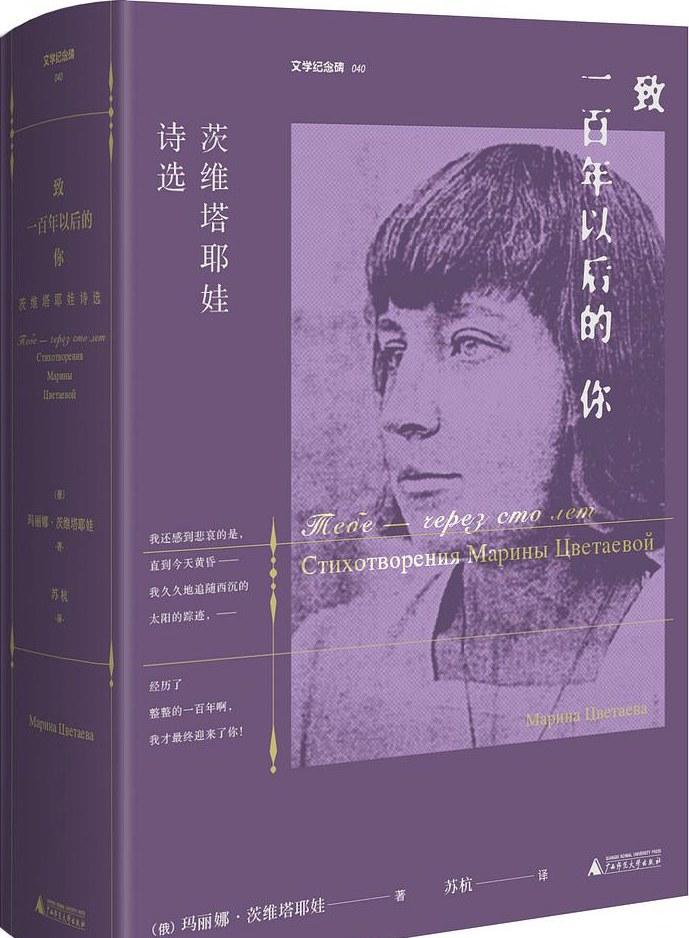

To You A Hundred Years Later: Selected Poems of Tsvetaeva, by Marina Tsvetaeva, translated by Su Hang, Guangxi Normal University Press, Shanghai Bebet, September 2021 edition, 536 pages, 78.00 yuan

Regarding the relationship between poetry and the times, I felt more and more that there was a sentence that was particularly weighty, constantly hitting the heart like a lead hammer: after Auschwitz, it was barbaric not to write poetry! When the wind and snow and cold solidify the river, only poetry is the only warmth and hope. Tonight, when public opinion is turning over and cold rain knocks on the window, reading Marina Tsvetaeva's "To You A Hundred Years Later: Selected Poems of Tsvetaeva" (translated by Su Hang, Guangxi Normal University Press, September 2021, 2nd edition), I feel particularly deeply.

This selection of Tsvetaeva's poems is based on the 1991 translation of the same book title and translator of the Foreign Literature Publishing House, and Wei Dong, the curator of the "Literary Monuments" series and senior literary editor, not only gave a very detailed introduction to the relevant situation of the reprint of the translation in the "Afterword" of the book, but also briefly reviewed the translation, publication, and acceptance of Tsvetaeva's works, biographies, and memoirs in China. This reprint of To You A Hundred Years Later: Selected Poems of Tsvetaeva is not supplemented or revised in the selected poems, and includes more than a hundred poems from various periods of the poet's life; however, three important introductory texts are added to the appendix. First, Korkina, a senior expert in Tsvetaeva studies, wrote a preface to the 1990 edition of Tsvetaeva's Selected Poems by the Soviet Writers' Publishing House, "The Poetic World of Marina Tsvetaeva", which profoundly examines the close connection between Tsvetaeva's poetry and its life and time; second, Tsvetaeva's biographer Anna Sakiyants' "Two Poets — Two Women — Two Tragedies" (Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva), From a comparative perspective, the different life destinies and poetic qualities of the two poets are revealed; the third is the Russian-American literary critic Mark Slonin's "The Fate of the Poet: Marina Tsvetaeva", the author and Tsvetaeva met during the Prague period, and has vigorously promoted the poet's work. In mark Slovene's essay, selected from his monograph Soviet Russian Literature (translated by Pu Limin and Liu Feng, Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 1983, according to Oxford Publishing House, 1977), Wei Dong believes that the book is "different from the previous History of Soviet Literature, with a wide range of scope and strong sense of problems, especially many of the writers mentioned are unheard of for Chinese readers." The Shanghai Translation Society launched the translation of the book in 1983, which was the first to be popular, and the book has not become obsolete so far, and it is worth reprinting." It is very true that I have benefited greatly from reading this work on the history of Soviet Russian literature since 1984. Incidentally, the selected poem, The Poet's Fate: Marina Tsvetaeva, is from chapter 23 of the original book, "The Fate of the Poet," and deals with the three poets, Mandelstam, Akhmatova, and Tsvetaeva. The chapter begins with an explanation of "destiny": the encounters and rises and downs of his works are similar, on the one hand, they are highly regarded and have a large number of readers, on the other hand, most of the works can only be circulated and read in manuscript form, and until the 1970s, soviet officials still did not allow the works of these three poets to be printed in large quantities. The section "Marina Tsvetaeva" in this chapter (pp. 270-278) is included in its entirety as Appendix III, but a careful comparison with the translation of the original book reveals two differences. First, there are amendments to the individual translation methods of the present selection, correcting the mistranslation in the original translation; second, there are many places in the present selection that have been deleted or changed, and this difference between the previous and subsequent versions can be recorded as a micro-historical material for the revision of the words. The "Editor's Epilogue" concludes, "Tsvetaeva's classicity stems from her ups and downs in life and her enduring artistic world, and I hope that the 'Literary Monument' will continue to excavate Tsvetaeva as a 'classic writer'." It should be said that the inclusion of this selected poem of Tsvetaeva in the "Monument to Documents" series of reprints will certainly be welcomed by the reading community.

The life of Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941) was both difficult and tragic, as well as proud and passionate about life. Born into an artistic family, she wrote poetry at the age of six, and published her first collection of poems at the age of eighteen, which was praised by her predecessors in the poetry world. In the storm of war and revolution, her fate was filled with the pain of parting from her family and living in a foreign country. But the only thing she didn't abandon was her obsession with poetry and her desire to write.

The lyric poem "To You A Hundred Years From Now" was written in August 1919, and Tsvetaeva wrote in her notes: "Yesterday I spent all day thinking about this event a hundred years later, so I wrote a few lines of poetry for it. These lines of poetry have already been written – the poems will be published. In a letter in 1924 he added: "And— mainly — I know how much people will love me in a hundred years!" "There is another version of the poem, which is translated here by the poet's 1940 final draft." As a man destined to die forever, / I personally wrote from under the Nine Springs / Written to you who came to earth a hundred years after my death—" (p. 139) "I hold my poem in my hand —/ Almost turned into a dust! I see you / Servant of the Wind and Dust, looking for the dwelling place where I was born -/ Perhaps the mansion where I died. "I also feel sad that it was not until dusk today —/ I have long followed the trail of the sun that sinks in the west,—— / After a whole hundred years, / I have finally welcomed you!" (p. 142) The poet sees poetry as a life and a call to the future, writing in her January 1913 preface to her new book: "It has all happened. The lines of poetry I write are diaries, my poems—proper noun poetry. All of us will pass. In another fifty years, we will all be under the dirt. Beneath the eternal sky, there will be a new set of faces. I want to shout out to all those who are still alive: Write, write a little more! Fix every moment, every gesture, every breath! (p. 384) Nothing is more eternal between life and death than poetry, and To You A Hundred Years From Now expresses a firm belief in this. But the poet also foresaw that her poetic fate would be full of ups and downs, and she wrote in her 1931 note "My Fate as a Poet" that although her name was passed among the poets, "it was all over quickly." (p. 389) Until the end of 1940, Tsvetaeva compiled her last collection of poems in the months leading up to her death, and she finally emphasized her fidelity to the words of poetry by adjusting the order of her works. Korkina's understanding of Tsvetaeva's approach is "Admittedly—at the moment when I was about to breathe, I was still a poet!" (p. 434) Behind her, Tsvetaeva's name was forgotten for a time, and it was not until the 1960s that Tsvetaeva and her poetry began to be rediscovered. This year is the 130th anniversary of the poet's birth, and now I come to read "To You A Hundred Years Later" in the cold wind of the southern country, as if in all the poems, "After a full hundred years, I finally welcomed you!" ”

Poetry is not only her life, but also her highest sustenance for emotion. In 1926, three famous poets—Rilke of Austria, Pasternak of Soviet Russia, and Tsvetaeva—exchanged letters. They were on opposite sides: Switzerland, Moscow, Paris; they had not yet met each other. In less than a year, the three of them exchanged nearly a hundred letters, and it was only half a century later that they became known to the world. Beijing World Literature, No. 1, 1992, selected fourteen of these letters, and Liu Wenfei's translation of "Three Poets Shujian" was published in the Central Compilation Publishing House (1999) and the East China Normal University Press (2018, with the title "Intertwined Flame"). It began when Pasternak was moved to tears and silence when he learned that he was known and appreciated by Rilke; when he wrote to Rilke, he introduced to Rilke, the female poetess Tsvetaeva, whom he admired, and asked Rilke to give her a copy of the Duino Lamentations with an autograph inscription. In a letter to Tsvetaeva, Pasternak said, "I am eager to talk to you, and I immediately perceive the difference." It's like a gust of wind sweeping across the hairline. I can't resist writing to you but want to go out and see what changes in the air and sky when one poet has just called out to another. In 1993, I talked about that strong reading feeling in the article "The Poet's Love": "Every speck of dust that is aware and believed in nature because of the inner desire and call is changed as a result, which is the true love of the poet." The female poets are also full of tenderness and love for Rilke and Pasternak, which is platonic poetic love. In the secular 'love triangle', it is impossible to understand the ocean's devotion to the breeze and the sky, it is impossible to understand the humanity, fate and love contained in the 'poem', and it is impossible to understand the mutual attachment between every willow and every little spark. (Li Gongming, Carnival on the Left Bank, Haitian Publishing House, 1993, p. 145)

Closely linked to Tsvetaeva's poetic fate is her homesickness and painful experiences after returning home. In the seventeen years of hardship in a foreign country, her poetry is full of nostalgia for Russia ("I greet the Russian rye...", "Song Ming", "Elderberry", "Motherland", "Nostalgia, this has long been ...") But what pained her most was that there was no room for her to live as a poet, whether in other places or in her homeland. Mark Slonin said: "She once said to a friend: 'I am superfluous here. It would be unthinkable to go over there; here I have no readers; over there, though there may be thousands of readers, I cannot breathe freely; that is, I cannot write and publish. But what happened to her in Moscow far exceeded her terrible predictions. (p. 469) Tsvetaeva is not entirely unaware of the situation in the homeland that has become "over there." As early as 1921, in "The Poetry and Revolution of Russia", Ilya Ehrenburg divided modern Russian poets into four categories according to their attitude towards revolution, and Tsvetaeva and Balmont were classified as the first category- poets who denied the revolution. Korkina argues that Tsvetaeva is consciously unable to accept what is happening in Russia, which has something to do with her own personality, and she adds an important fact in her notes: In response to the view that "Tsvetaeva did not understand and did not accept the revolution", Tsvetaeva's daughter A.C Efron cited the fact that her sister died of starvation in February 1920, adding: "Is there anything clearer and more unacceptable than this?" (pp. 398-399) In 1937, on the eve of Tsvetaeva's daughter's departure to return home, Bunin, a writer who had left Russia after the October Incident, said to her, "Fool, go ahead, you will be sent to Siberia!" After a moment of silence, he added in a worried tone, "If only I were your age... Even if it is Siberia, even if it is deported, I recognize it! Because that's Russia after all! (Ariadna Avron, "Remembering Marina Tsvetaeva: Memories of Her Daughter", translated by Gu Yu, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2015, pp. 18-19) This kind of homesickness and final choice in the face of the prospect of suffering is also a sign of the times, and no one can escape the spread of history. Tsvetaeva also embarked on her journey back in June 1939, of course because after her daughter's return, her husband, Sergei Evron, also returned in 1937 for an incident related to the Soviet government. In this case, she was unable to remain in France with her son.

Although Tsvetaeva knew that going back was a difficult road, she certainly did not expect to suffer so much pain. What she couldn't know was that the Soviet Union was in a harsh era. "Whistleblowing and suspicion have become the norm of life. The upright, honest, and innocent man who committed no crime was imprisoned, tried, shot, and declared an 'enemy of the people'. People who have returned from abroad, or who have traveled abroad on business, are often regarded as foreign spies and spies. (Ariadna Averon, "Remembering Marina Tsvetaeva: Memories of Her Daughter", translated by Gu Yu, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2015, p. 21) Two months after returning to China, her daughter Aria was suddenly arrested late on the night of August 27; on October 10, her seriously ill husband Sergei was also arrested. The next few days were spent running around to get news of their daughters and husbands, struggling for their own lives with their sons. In search of a shelter in Moscow, she asked the head of the Writers' Association, Fadeyev, for help, and was answered that there was not a square meter. In August 1941, she and her son Moore were evacuated to the small town of Yelabuga in the Tatar Autonomous Republic, and in order to earn a living, she went to Chistopol, the seat of the Moscow Writers' Association, and asked to move there and get a job as a dishwasher in the canteen to be opened by the Writers' Association Foundation, but was also refused. It was the last straw that crushed her. She returned to Yelabuga on 28 August and committed suicide on 31 August while her landlord was out. In her will to her son, she said, "Little Moore! Forgive me, but the further you go, the worse it gets. I was very sick and this was no longer me. I love you madly. Understand that I can't live anymore. Tell Dad and Alia—if you can see—that I love them until the last breath, and explain that I'm in a desperate situation. A month and a half after Tsvetaeva's death, her husband Sergei Evron was executed. In 1945 Pasternak, in a meeting with Isaiah Berlin, he mentioned Tsvetaeva's suicide in 1941, arguing that if it were not for the literary bureaucracy who was so desperate for her, it was simply appalling, and this might not have happened. (Isaiah Berlin, The Mind of the Soviet Union, ed. Hardy; translated by Pan Yongqiang and Liu Beicheng, Yilin Publishing House, 2010, p. 63) This is, of course, the direct cause, but it cannot be used to explain a phenomenon of the times. Tsvetaeva, like Yesenin and Mayakovsky, died by suicide. Before he committed suicide, Yesenin said that death was nothing new, but it was not more new to be alive; Mayakovsky, after hearing of Yesenin's suicide, said that death was not a difficult thing, and it was more difficult to live. Corkina argues that recognizing that there is no corner of the world that offers poetry a "secret freedom" and that poets can only exist in that freedom, she replies to that world with outright rejection. (Korkina, "The Poetic World of Marina Tsvetaeva", "To You A Hundred Years Later: Selected Poems of Tsvetaeva", p. 433) It can be said that the suicide of the famous Russian poet is a symptom of the times, and it also confirms the last pride and eternity in a life of suffering.

What happened to Tsvetaeva on her return is reminiscent of a similar experience with the famous historian of Russian literature she knew, D.P.S. Mirsky (1890-1939). Born into a prominent Russian family, Mirsky joined Denikin's White Guard units to fight the Bolsheviks after the outbreak of the Revolution of 1917 and completed his studies in history at Kharkiv University. In 1920 Mirsky, like many Russian aristocrats, went into exile and eventually settled in London, England, where he became a professor at King's College London in 1922 and as editor of the Slayonic Review, a publication of the academy, and soon became a well-known expert in Russian literature in Western European scholarship. In March 1926, when Mirsky invited the French expatriate Tsvetaeva to Visit England for two weeks, Tsvetaeva wrote to a friend that Mirsky had taken her "to eat" in London restaurants. In the same year, Tsvetaeva, in her essay "On the Criticism of Poets", expressed dissatisfaction with "foreign critics" such as Bunin and Gibius, and at the same time considered Mirsky's article to be a "comforting obvious exception" because he "does not judge poets from the point of view of superficial political characteristics". It is worth noting that Mirsky was also an active political commentator and activist, involved in the Eurasian movement. The movement split at the end of the twentieth century, and both Mirsky and Tsvetaeva's husband, Evron, belonged to the pro-Soviet left of the movement, and both later returned to the Soviet Union. Mills returned to the Soviet Union at the end of September 1932 and soon realized his alternative identity, so he retreated from the socio-political field to literature and engaged in literary studies with Gorky's support. Although he joined the Soviet Writers' Association and participated in the stalin canal (1934), he was finally doomed when Golje died in 1936. On July 23, 1937, Mirsky was arrested by the secret police, sentenced to eight years of labor camp for espionage, and exiled to the Soviet Far East. On June 6, 1939, Mirsky died in a "labor camp for the disabled" near the city of Magadan. (See Des Mirsky, History of Russian Literature, translated by Liu Wenfei, The Commercial Press, July 2020, translator's preface) Mirsky's experience is simply a precursor to the fate of Tsvetaeva and her husband.

The included E.B Korkina's The Poetic World of Marina Tsvetaeva is a monograph on Tsvetaeva's poetic creation, arguing that although Tsvetaeva's early work is similar to Akmeyerism, her poetry has always belonged to any literary trend and genre in form, and she is unique and cannot be classified. This is a relatively unanimous view of the academic community. As early as 1926, de S. Mirsky's Contemporary Russian Literature (1881-1925) (in 1949 Professor Whitefield co-edited it with History of Russian Literature: From Antiquity to Dostoevsky's Death (1881), published in London under the title A History of Russian Literature, noted that Tsvetaeva's "very unique and novel poetic talent was at a higher level of poetry... Her development is independent of all genres and guilds, but it also embodies the general tendency of the most dynamic part of contemporary Russian poetry, that is, to flee from the shackles of 'theme' and 'thought' to the free world of form. (DeS Mirsky, History of Russian Literature, translated by Liu Wenfei, The Commercial Press, July 2020, p. 653) He analyzes specifically the uniqueness of Tsvetaeva's poetry in its rich mutation of rhythm: "She was a master of broken rhythm, and this rhythm gave the impression of hearing the hooves of a galloping horse. Her poetry is entirely fiery, fiery and passionate, but not sentimental. Not even emotional poetry in the true sense of the word. Its 'appeal' lies not in what it expresses, but in the sheer power of emotion. And as an authentic Russian poet, although she had no sense of mysticism or religion, her poems always resounded with the tone of folk songs. Her long poem "The Maiden King" is a true miracle: a superb drawing on the Russian folk singer's method, and is an excellent fugue with folk themes. (Ibid.)

The uniqueness of Tsvetaeva's poetry is closely related to the poet's frank personality. The famous Russian-American poet and literary critic Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996) elaborated on Tsvetaeva's poem "New Year's Greetings" completed in 1927 in his long essay "Footnotes to a Poem", arguing that "in many ways this poem is not only her own work but also a landmark of Russian poetry as a whole". (Joseph Brodsky, Less than one, translated by Huang Canran, Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House, 2014, p. 168) He points out that Tsvetaeva was an extremely frank poet, probably the most frank poet in the history of Russian poetry. She kept no secrets, much less her aesthetic and philosophical creeds, which were scattered in her poetry and prose, and were often revealed in first-person singular pronouns. (Ibid.)

Mirsky admired Tsvetaeva's poetry, but disliked her prose very much, saying that "to be fair, her prose to date has been sloppy and hysterical, the worst prose ever written in the Russian language." (Ibid. Mirsky, p. 654) This is clearly a serious bias. Brodsky, who wrote The Poet and the Essay, devoted herself to Tsvetaeva's prose achievements, argued that Tsvetaeva's transliteration of prose as a poet was nothing more than a continuation of poetry in other ways, which "greatly benefited prose": "This is exactly what we encounter everywhere—in her diaries, in essays on the thesis, in novelized memoirs—to re-implant the methodology of poetic thinking into the prose text, to make poetry grow into prose." (Ibid., cited in Brodsky, p. 151) He spoke highly of his prose: "Whatever prompted Tsvetaeva to turn to prose, and no matter how much Russian poetry suffered as a result, we can only be grateful to God for such a turn." (Ibid., p. 163) Brodsky, with the sensitivity of a poet, found in her consistent poetic aesthetic principles and special poetic techniques (sound association, root rhyme, semantic cross-line, etc.) in her prose, pointing out that the high-pitched sound quality characteristics of her poetry are also presented in her prose, "The sound quality of her voice is so tragic that it ensures that there is always a certain sense of ascension, no matter how long the sound lasts." This tragic quality is not entirely the product of her life experience; it precedes her life experience." (Ibid., p. 154) He reminds the reader not to forget that Tsvetaeva has a background in three languages, most notably Russian and German, so that her work is essentially rooted in language, and its source is words. Brodsky goes on to point out that one of the striking features of Tsvetaeva's work is the absolute independence of her moral assessment, "which coexists with her astonishingly intense linguistic sensitivity." (p. 161) This is an important research perspective on the relationship between linguistic sensitivity and moral and ethical truth. Brodsky, speaking in 1979 of the fact that the complete works of Tsvetaeva had not yet been published in Russian or abroad in the Soviet Union, pointed out: "Contrary to those peoples who have the privilege of enjoying legislative traditions, electoral systems, etc., Russia is in a position where it can only understand itself through literature, and therefore to obstruct the literary process by destroying even the works of even a minor writer or by treating them as non-existent is tantamount to committing a hereditary crime against the future of this nation." (p. 163) This is an even more important question worth pondering.

When Tsvetaeva felt that her life would be swallowed up by the darkness inside and outside, she wrote the following verse: "It is time to take off the amber, / It is time to change the dictionary, / It is time to put out the lamp on the door / Extinguish..." (To You A Hundred Years Later: Selected Poems of Tsvetaeva, p. 442) The poet died, the darkness and suffering of the world continued, but the light of the poet left in our spiritual life will never be extinguished. Tsvetaeva wrote in her "dedication" to her Poem of the Mountain, written in January 1924 and finalized in December 1939, when she returned to the Soviet Union: "Just shake it – it will unload its load, / The mind will rush to the top of the mountain!" / Let me sing the praises of pain - praise my mountain. /...... Let me stand on the top of the hill, / to sing the praises of pain. (pp. 342-343) A poet who praises pain, this is the haughty image that Tsvetaeva left on the eternal poetic canopy.

Editor-in-Charge: Huang Xiaofeng