Summary: The ancient Jews understood life as a series of relationships that man and God have concluded in this world, and death is the end of these relationships. The Jews chose a path of overcoming individual vulnerability with national collectivism, turning the individual into a link between ancestors and descendants, eliminating individual anxieties and worries about death through the powerful bonding role of the family and religious communities. The Jews also developed the concepts of ghosts and hades from the totality of the spirit and flesh, the ghost represents the low stage of life, it will disappear with the disintegration of the body, hades is the temporary dwelling place of the ghost, it can not really affect the life of the world, thus fundamentally eradicating the basis on which the worship of the dead is based; the totalism of the spirit and flesh also has a certain connection with the Jewish burial custom, this connection has been proved in the biblical literature. With the infiltration of Hellenistic culture, Jewish society diverged, and among religious intellectuals and ordinary people, the concept of the afterlife, with the main content of resurrection, judgment, heaven, and hell, was born, which originated from the inherent traditions of the Jews and benefited from the influence of the surrounding Gentile ideas.

Original source: Historical Research, No. 05, 2014

The Jews have historically been considered a people full of realism, and they seem to think less deliberately about the transcendental afterlife. However, from the 1990s onwards, people found that this traditional view did not necessarily stand the test of time, and academics began to reflect on the Jewish view of death and the afterlife. Wen Xing was one of the initiators, who made a preliminary collection, classification, and comparison of the ancient Israelite and later Christian concepts about the end of life and the afterlife, based on popular old and new testament texts, with a focus on revealing and highlighting the historical connections between the two. He was followed by Faschbein, who focused on the essential nature of the Jewish view of death, which in his view, since the Bible regarded the love of God as a basic Jewish duty and lifelong pursuit, death inevitably became the ultimate and final completion of the love of God, which was the most important ideological basis for the Naturalistic view of death in Judaism. Jewish Rabbi Kirman further explores the idea of resurrection and immortality in the Jewish view of death, arguing that although the Jews lack a clear conception of heaven and hell similar to that of Christians, their unique idea of immortality gives real life a new vitality and spirit. Another Jewish Rabic Lémore based on an in-depth investigation of Jewish documents such as the Talmud and related historical sites, on the basis of which he vividly outlined the trajectory of the development of Jewish thought of death after the 2nd century AD. A group of American Jewish rabbis and university scholars, represented by Remore, have also written articles on the subject of death, and they have explored the general views of contemporary Jews on death from the perspective of funeral customs and other aspects. Eleksch, on the other hand, based primarily on evidence provided by the Jewish historian Josephus' Ancient History of Judaism, gave a more detailed account of Judaism's idea of the afterlife and explored the differences between the Jewish and Greek views of death. In addition, the domestic scholar Jia Yanbin gave a linear overview of the Jewish view of death from the rabbinic period to the present, focusing on the philosophical connotations and theological significance of the Jewish view of death.

Most of the above research focuses on the Judaism of death after the Rabbinic period, and the individual narratives, although they also relate to the early Judaism and biblical era, are only static theoretical generalizations and analysis on a certain cross-section, and do not seem to pay enough attention to the historical evolution of the Jewish view of death. This paper intends to be based on these research results, with the help of historical analysis methods, mainly starting from the Hebrew Bible text, combing the ancient Jewish idea of death and its historical development, the purpose of which is to prove: the realist spirit of the ancient Jews does not mean that they do not attach importance to death, they do have a unique view of death; moreover, in the long river of historical development, the Jewish view of death is not static, it has actually undergone a series of subtle and tortuous changes. These changes vividly reflect the long-standing interaction between Jewish culture and the surrounding heterogeneous cultures.

Death as an integral part of life

It is true that the Hebrew religious tradition has focused primarily on God's relationship with the nation of Israel as a whole, and therefore pays less attention to issues such as the death of the individual and his or her whereabouts after death. But that doesn't mean the ancient Jews didn't think about death at all. In fact, any great religion was born to achieve the transcendence of death, and Judaism is no exception, and the Jewish concept of death is the basis of the Hebrew religious belief, which largely restricts the social life and customs of this nation.

The ancient Jewish view of death was an integral part of their view of life, and this view of life can be traced back to God's creation of mankind. As we all know, Genesis contains two very different creation stories. The first story tells that After creating all things in the world, God created people in His own image, including men and women. (11) Since the story does not address what God created man by, some later Christian fathers believed that God was created out of nothing, an explanation that was nothing more than a demonstration of God's omnipotence. The second story recounts that God created the first man with dust from the ground at the dawn of chaos and blew the breath of life into his nostrils to make him a living man; God then created all things in the world, and finally extracted a little flesh from the first man and created the first woman. (12) Obviously, the second story has a stronger breath of ancient Hebrew life and is therefore more helpful in understanding their attitudes toward life and death. In this story, human life is said to have originated from the earth, as with all other things, so that death, the departure of life, is naturally considered to be return to the earth; and since the original man became a living man by being infused with the breath of God, man, from body to soul, should be understood as being given by God. This was the original basis of the relationship between man and God in the minds of the Jews. According to genesis, God was content with His creation, and He placed the first human beings in the lush Garden of Eden to allow them to enjoy all that God had created. If the story only ends here, the completeness and beauty of the world cannot be doubted, and the death that has come to the earth cannot be discussed. As the Jewish rabbis said, "If God praises His creation, who can condemn it?" (13) Shortly after the events of creation, however, a turning point emerged: God admonished the first man, Adam, that he could eat the fruit of the tree of life and other fruits, but must not eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge which discerns good from evil, or that he would undoubtedly die; (14) contrary to God's will, the first mankind, at the instigation of the python, tried the fruits of good and evil. (15) This is both the beginning of human death in the biological sense and the beginning of evil in the moral sense, and since then death, as one of the greatest evils, has been firmly inscribed in the annals of Jewish thought, and the tree of knowledge has become the authentic tree of death.

The religious moral conveyed to us by this story is clear: although the tree of death and the cunning python are in fact God's creations, because God has given a clear warning in advance, man is solely responsible for the consequences of this choice, since he has made his final choice. In other words, human death is not by God's will, but by human self-inflicted. The Bible tells us very clearly that death, and all evils closely related to death, were not created by God: "God did not create death, and the death of living beings did not make him happy. God created all things, all things are able to survive, and all things He has created are good and beautiful. (16) Augustine, the later Latin father of Christianity, blamed death on the abuse of god-given free will by man, saying that God "created man whose characteristics are between angels and beasts—if he obeys the Creator, regards him as his true master, and follows his teachings, he will be with the angels, attaining immortality and endless happiness, and renouncing any death; but if he uses his free will to disobey and thus be guilty of his Lord God, he will be like a beast, Subject to death, become a slave to one's own desires, and destined to suffer eternal punishment after death". (17)

Although death has appeared, a merciful God still tries to prolong human life as much as possible. But since death in the biological sense is equated with evil in the moral sense, the length of life must be directly proportional to the number of virtues—the higher the virtue, the longer the lifespan, and vice versa. During some of the critical periods of the formation of the Hebrew Bible, Jews lived in difficult circumstances of being destroyed or displaced to a foreign country, and they had a deep nostalgia for the glorious distant past, which inevitably left its mark on the biblical literature. Some books of the Bible record the longevity of many important people who belong to natural death, and in general, one generation is not as good as a generation. For example, the patriarch Adam lived to be 930 years old, his son Seth lived 912 years, and his grandson Enosh lived 905 years; (18) After the Great Flood, the life expectancy of man was much worse than before, although the favored so-called "second generation ancestor" Noah could still live to the age of 950, (19) but his descendants deteriorated, such as Flash lived 600 years, his son Afasa lived 438 years, Afasa's son Sharaya lived 433 years, and Sharaya's son Xilu lived 230 years. Nakho, the son of the West Deer, lived only 148 years; (20) the situation was even worse later, and the Hebrew ancestor Abraham lived 175 years has been considered extremely rare, considered to be "old and old", and his wife Sarah only lived 127 years. (21) Subsequent accounts include that Isaac lived 180 years, (22) Jacob lived 147 years, (23) Moses lived 120 years, (24) Joshua lived 110 years, and (25) Eli lived 98 years. (26) These accounts of age may seem meaningless from a purely historical point of view, but they reveal an indisputable fact: at least for the ancient Jews, high life was God's reward for the virtuous, because the people listed in the Bible were virtuous. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37-100 AD) once pointed out that the longevity of the ancients was certainly related to the healthier food of the time, but more importantly because of their virtues, they were specially favored by God because they loved God. (27) But why does the life expectancy of people become shorter and shorter over time? There is only one answer, and that is the repeated deviations and offenses of the Israelites against God's will, the moral decay of the nation of Israel as a whole. Thus, the reduction in age became a necessary wake-up call for God to the overall moral decline of the Israelites.

Interestingly, this Jewish view of death, which began with the rebellion against God's will, did not lead to an original sin theory that developed in the later Latin Christian world in the context of Hebrew culture. The essence of original sinism lies in the fact that, on the one hand, the moral decay and physical death of the individual are attributed to the disobedience of the common ancestors of mankind, and on the other hand, it highlights God's redemption and the state of exoneration from the world. The Hebrew culture, on the other hand, emphasized the common destiny of a people in its relationship with God, and that destiny rested in this world rather than in the other, so that although it provided the mythical basis for the theory of original sin to later Christianity, it was impossible to develop any idea of original sin itself. However, the Jewish concept of sin is still derived from its unique view of death. As mentioned above, Genesis already sees death and evil together as a direct consequence of the disobedience of the Patriarchs, and evil is undoubtedly the only source of sin; after sin, there is naturally a way to forgive sins, but the Process of Forgiveness of Sins by the Jews is based on this life and this world. According to Skassone, since the Babylonian Captivity, the pardon of sins has been at the center of the entire sacrificial ritual in the Temple of Jerusalem; when the Temple was destroyed by the Roman army in 70 AD, one of the most asked questions among Jews at that time was: How can people get forgiveness for their sins from now on? (28) Thus the importance of forgiveness of sins in jewish religious life.

Although death stems entirely from the fault of man himself, according to the traditional Hebrew philosophy, any creation other than the Creator himself will inevitably eventually decay and disintegrate, and human beings, as God's creation, will not be able to escape the doom of death; since life is considered to come from the breath given by God, death is understood as this breath wandering out of the body, and the body that lacks the breath of life becomes dust and returns to the earth. The book of Job says, "If God were to take back the breath of life, then every living person would die and return to dust once again." (29) The Psalms also say, "When you take away their breath, they die and return to the dust from which they came." (30) According to the story of Creation, at the time of death, it is clearly the human body, not the soul, that returns to dust, and the soul, which is the breath of God, naturally returns to God. The words of Job and the Psalm writers are not unfounded, for God, in announcing the judgment of death to the patriarchs of mankind, said in an unmistakable tone, "Thou shalt come from the dust, and you will return to the dust." (31) This phrase later became an indispensable liturgical term for Jewish and Christian funerals. Thus, death, like life, is seen as a natural process. In this case, all normal deaths are acceptable in a calm manner. The Ponsila Commandments warns, "Do not be afraid of the judgment of death, but remember that those who have come before you have met death, and those who have come after you will also encounter death." (32) The Woman of Tegothyah, as a lobbyist, said to King David, "All of us are mortal, like water poured on the ground, which cannot be recovered." (33) If it is said that ordinary death is not enough to be afraid of, then the end of a long life is a fortunate thing that people yearn for. God had told Abram, "You will die of great age and be buried." (34) This is a reward for Abram's superb virtue. Another virtuous man, Jobin, withstood God's test of him, and God prophesied to him through Elifa, the mantle, "You will live a long life before you return to the grave, as if the wheat had ripened at the time of harvest." (35) This naturalistic view of death prevented the Hebrews from detaching themselves from the bonds of this life, and it is no wonder that some people think that the Jews did not value death. The author of the Psalms asks God to give us such a life: "Fill us with your love in the morning, so that we may rejoice and rejoice for the rest of our lives." (36) The eagerness to pursue happiness in this world is no less than that of the ancient Egyptians, who were optimistic about real life. In the Moses commandment, God asked the Israelites to choose life and happiness: "Behold, I have placed before you today life and happiness, death and calamity. If you choose life, you must love your Lord God, pay attention to His voice, and fast against Him..." (37) Here, God's demands actually represent the ordinary desires of life and the pursuit of ideals in Jewish society.

In fact, the Jews' emphasis on life and their transcendent attitude toward death are closely related to the living environment in which they live. As we all know, the land of Canaan, which Abraham led his people to move into with great hardships, was at the ancient transportation hub between the East and the West, strangling the throat of the three continents of Europe, Asia and Africa, and was a place where soldiers had always fought; historically, as the promised land given by God to the Jews, its "honey and milk" of its abundance was more often exchanged for the tears and blood of countless Jews. This overly sinister human environment made it easier for the ancient Jews to be favored by the god of death. For the diaspora Jews who were constantly drawn into the vortex of war and then exiled, the anxiety caused by the hardships of life and the fragility of life was beyond imagination. In an age when death was the norm and survival was the exception, the Jews had undoubtedly honed enough courage to deal with death that could come at any time. In their view, since tomorrow is unpredictable, today is precious, so they regard each day of their individual life as a special gift and gift from God. It is said that today's Jews, when making an agreement with a friend, still do not dare to say "Let us see you tomorrow" with certainty, but instead say with reservations, "Let us see each other tomorrow if God pleases", or "Let us see you tomorrow, but I cannot guarantee it"; (38) This is both a foresight in the complex and ever-changing conditions of life and a mark of suffering engraved on future generations by their ancestors.

Since death is an unavoidable end for every mortal, a method beyond death must be invented, which is equally necessary for the Jews with a tradition of realism. Ultimately, the Jews chose a path of overcoming individual weakness with national collectivism, turning the single person into a link between ancestors and descendants, and through the strong bond between the family and the religious community, they eliminated the anxiety and worries of the individual about death. On the one hand, Jews saw death as a reunion with deceased relatives, so family cemeteries had a special significance. Jacob did not want to be buried in Egypt, so he made a will: "Do not bury me in Egypt, I will be taken out of Egypt after I die and buried in the graveyard of my ancestors." (39) According to Joseph, after the death of Joseph and his brothers who lived in Egypt, the bodies of their descendants were brought back to Canaan by their descendants and buried in the ancestral tombs of Hebron. (40) Many later kings, such as David, Solomon, Joasch, and Asa, were buried in their ancestral tombs after death, which was called "sleeping with his ancestors." (41) Ordinary people are usually buried "in their father's grave" after they die. (42) According to Wenxing, the yearning for ancestral tombs was initially nothing more than the habit of family burial, but this initial habit later took on a deeper meaning, and words such as "sleeping with ancestors" became solemn procedures used to refer to death, and also emphasized that blood ties transcended the tomb. (43) On the other hand, having many descendants is considered one of the important signs of success in life, so one should leave behind his or her offspring before dying. Although Abraham was a good man, he was suffering from old age and childlessness, and his heart was inevitably secretly anxious; fortunately, God did not forget the old man, who made a promise to fill his children and grandchildren, and the promise was quickly fulfilled. (44) Job, who withstood the trials of God (through Satan), received a similar reward. God prophesied to Job through Eliphas the Mantle: "Your descendants will be prosperous in the future, and your descendants will be as multiply as the grass on the earth." (45) In sum, in ancient Jewish society, if a person could produce many descendants while alive, and when he died he could be buried in the graveyards of the patriarchs, and at the same time he could end up with a high life, then most of the person would laugh at death, because he had enjoyed all the years and was therefore worthy of himself, and he continued the life of the family through the blood of his descendants, and thus worthy of his ancestors. This path to transcending death through familial collectivism does have much in common with the traditional beliefs of ancient Chinese. However, a major disagreement cannot be ignored: because the Jews developed a monotheistic belief earlier, ancestor worship similar to the traditional Chinese society could not find a place to live; the Jews simply understood death as the end of their relationship with God, so that the dead did not have the problem of being deified.

Of course, due to differences in social status and living environment, each specific individual's understanding of death is also very different. As the Bensilla Wisdom Says: "The word death is quite painful for some people who live richly, live in peace, carefree, and have a strong appetite; the word death is quite popular for those who live poorly, frailly, old-fashioned, worried, blind, and hopeless." (46) Certain special and bad circumstances often cause some people to abandon themselves. The great prophet Elijah, persecuted by Jezebel, queen of Israel, prayed to God to let him die sooner. (47) The good man Job, under the blow of calamity, cursed his birthday: "God, may my birthday be cursed; may the night I was conceived by my mother be cursed!" He thus developed a pessimistic and world-weary mood: "I don't want to live, I am tired of life; let me go, my life is meaningless." (48) The prophet Jonah, furious that God had not destroyed the city of Nineveh, begged God to give him a swift death: "Lord, let me die, it is better for me to die than to live." (49) On the contrary, others were extremely afraid of death and life, such as Hezekiah, the king of Judah, who wept loudly as he was dying, begging God to spare him death, and finally gaining an additional fifteen years of life. (50) However, neither the extreme yearning for death nor the extreme fear of death can be regarded as a few exceptions to the old Jewish conception of normalcy, and they do not represent the mainstream of society.

2. Ghosts, Hades and Burials

The Hebrew Bible tells us that man, as God's creation, is made up of both body and soul. The sacredness of the soul as the breath of God goes without saying; and although the body comes from the dust of inferiority, it can be turned into a treasure by the help of God's creation, and its value and dignity are highlighted by God's role. With the help of this biblical idea, the ancient Jews understood human life as an organic unity of the soul and the body, in which neither the soul nor the body could function alone, and therefore the true death was the disintegration of the soul and the body. According to this holism principle, after death in the usual sense, because the body decays and dissolves after a long or short period of time, the soul must still remain in the body during this period, but at this time life is at a low ebb, and this life in the low ebb stage is usually called "ghost". Of course, ghosts cannot last long, and in general, when the body of the deceased finally dissolves, the ghosts will disappear with them. The existence of ghosts constitutes the "afterlire" (afterlire) with Hebrew characteristics.

Ancient Jews believed that ghosts inhabited Hades. The ancient Hebrew word for "Sheol" actually refers to the dark underground world, similar to the ancient Greek Word hades. The premises, though eerie, did not have the moral function of punishing evil. It was only later that it gradually evolved into a waiting place between the wicked going to hell and the good going to heaven, but it was neither hell nor heaven in itself, but merely a temporary dwelling place for the souls of the dead. (51) Thus, when the ancient Jews spoke of someone going to Hades, it generally did not have the meaning of a value judgment, but simply meant that someone had passed away. The Hebrew Bible mentions ghosts and hades in many places. In his reply to Billeda, Job mentions: "The ghosts of the dead tremble in the underground rivers, and hades are revealed before God." (52) Isaiah said of Babylon, "Hades is preparing to meet the King of Babylon. The ghosts of the powerful are being shaken while alive. The ghosts of the kings are rising from their respective thrones... You used to be entertained by the sound of the harp, but now you are in the world of Hades. (53) In the Jewish context, since there is a conception of the totality of the spirit and flesh, there is no essential difference between "hades" and "the grave", except that the former is relative to the ghost and the latter to the corpse. Segor rightly pointed out that the ancient Hebrew word "Hades" can mostly be reasonably understood only as "grave" or "grave", which is synonymous and symbolic of "death" in the usual sense. (54) Thus in the Bible, when referring to death, the words "hades" and "grave" are often used interchangeably or in conjunction. For example, God prophesied to the Israelites through the prophet Ezekiel: "The Egyptians will fall into Hades and lie down there with the unbelievers... The Assyrians and their warriors were all in graves, and they all died on the battlefield, and their graves were in the deepest part of Hades. (55) The author of the Psalms also sings, "My heart is full of tribulations, and my life is near Underworld." I will be in the same line as those who descend the grave, and my strength has been exhausted. ”(56)

In contrast to the surrounding Gentiles, in the eyes of the ancient Jews, only the living could have relations with God, praise God, and ask For God's blessing and protection; once they died, they cut off contact with God and thus could not get God's protection, which was regarded as the greatest misfortune of death. The greatest feature of the religious beliefs of the ancient Jews was the view of their own peoples as the priority races that God had promised to be saved. To attain true salvation, one must keep the covenant made by the ancestors with God; but in real life, due to man's inherent sinful tendencies,(57) they repeatedly break their covenant with God, and death is treated as a punishment for people's breach of contract. People who are created in the image of God and infused with the breath of God can not die, but now they must die for betraying God, so from God's point of view, death is expulsion from immortality, which can be said to be another form of "de-listing and remembrance". If survival is the theme of the Bible's praise, then death is the object of its lamentations. For example, the author of the Psalms speaks of death many times in a pathetic tone: "In Hades, neither remembers you nor appreciates you" ;(58) "I am forgotten like a dead man, abandoned like a waste" ;(59) "The dead cannot praise God, and no one who descends into the silent world can praise God." (60) "Will the dead rise up and praise you?" How can you tell your eternal love in the grave? (61) Bhalymi's student, Balu, said in prayer to God: "Those who have died and gone to hell can no longer breathe, and they cannot praise you or declare how righteous you are." (62) King Hezekiah of Judah also wrote in a hymn of thanksgiving: "In Hades no one can praise you, nor can the dead believe in your correctness and reliability." (63) In short, once a person dies, he is forgotten by God. Theoretically, since the dead have severed all relations with God, they cannot exert any meaningful influence on the world of the living on a moral level, for example, the living cannot derive any tangible benefit from the dead, and therefore the supplications of the dead become worthless.

The hades of the ancient Jews, the world of the dead, were neither a place of reward for the good nor a place of punishment for the wicked, but a kingdom in which the ghosts of all the dead temporarily inhabited, which became another major factor in the failure of the Jews to develop ancestor worship. However, exceptions also occurred from time to time, such as when Saul asked the witch to summon the ghost of Samuel. At the critical juncture of the Felicians' army, the king of Israel, Saul, asked god for help, but was refused, so he had to violate the laws he had made and secretly asked a witch to summon the ghost of the late prophet Samuel. Unfortunately, samuel's ghost did not meet Saul's request. (64) Later Christians ridiculed the event, such as the mid-3rd-century martyr Pionius, who preached in prison: "This evil witch is a devil herself, how can she summon the soul of a holy prophet?" Since the prophet was resting in the arms of Abraham, he certainly could not have been summoned by such a demon. (65) However, this failed process of summoning inadvertently reveals to us two basic points of the ancient Jewish understanding of ghosts: First, all laymen, even Saul, who is on the throne, could not perceive ghosts with the naked eye, and only a few wizards with the special skills of god-making could possibly gain the opportunity to meet ghosts face-to-face through some special ritual; however, with the development of monotheism in Hebrew society, witchcraft activities were gradually forbidden, except for individual dreams and visions. No one can see a ghost in the real world. Second, in the special case where it is possible to see a ghost, the only way to identify the ghost is to see what he is dressed, and the ghost's dress is actually the dress of the deceased before he dies. For example, the witch saw an old man in a robe, and Saul could immediately judge that he was the ghost of Samuel when he heard such an external feature. (66) This reveals once again that the ghost is merely a continuation of certain characteristics of his lifetime. Some argue that this story, as a special case, does not prove that the Jewish society of the time had the belief in the independent existence of the soul after death, as Segol pointed out after quoting this story: "Afterlife is at best a natural fact, and it has no significant significance for man's moral and religious behavior." Death does not bring the individual closer to God, and afterlife is not set for eternal rewards or punishments. The Torah does not require ritual or moral precepts for some kind of post-mortem life. (67) This judgment is undoubtedly objective, and the ghost of Samuel does nothing to help Saul's cause, which shows that the actual influence of the world of the dead over the living does not exist.

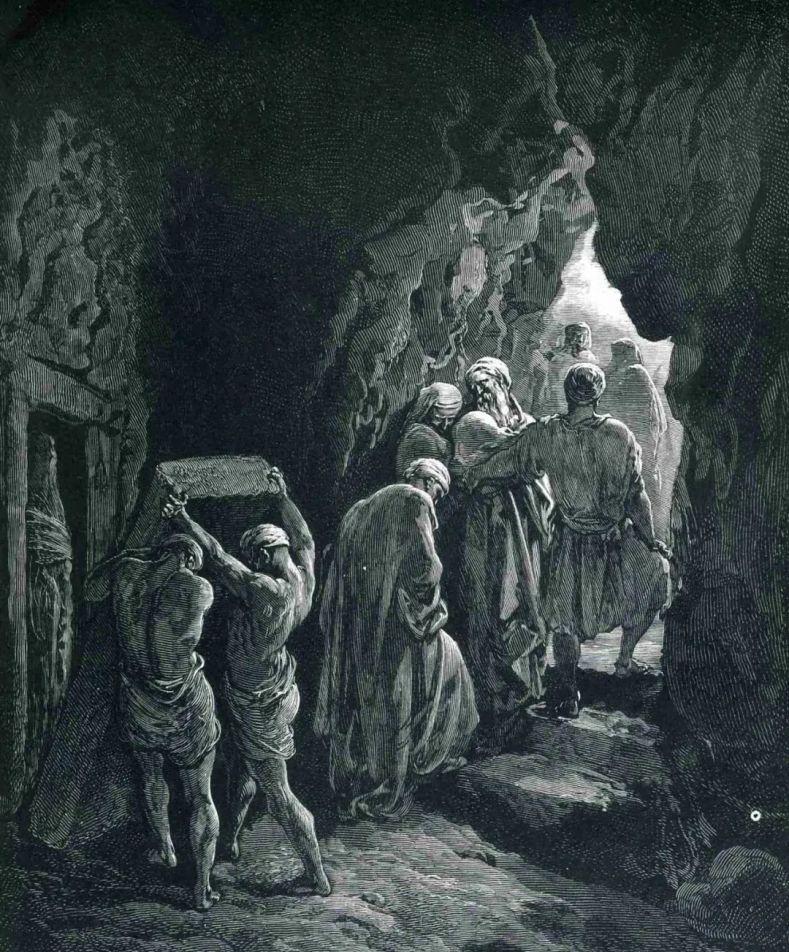

However, the world of the dead has no influence and does not lead to the fading of funeral matters. On the contrary, since the ancient Jews were a highly ritualized people, funerals must have been highly valued as an integral part of their ritual system; on the other hand, since the creation of life has been regarded as the starting point and milestone of the entire history of the universe, since the creation of life has been regarded as a symbolic event, since the logic of biblical thought has been regarded as the starting point and milestone of the entire history of the universe. Therefore, the serious attitude towards funeral matters actually reflects a high degree of respect for the value of human life. (68) From the information revealed in the Bible, the Israelites in the Canaanite region practiced burial, and fire was an insulting tactic they used against notorious criminals. For example, the Moses commandments stipulate that those who have sex with their mother-in-law are burned alive by fire with their mother-in-law and wife. (69) In general, the body must be buried; If important people are not buried after death, God will be angry. For example, during the reign of King David, there was a severe famine for three consecutive years, and it was only after asking God that Saul had a blood debt during his reign, so Saul's bones were obtained by the enemy And never buried. After arranging to pay off the blood debt, David retrieved the bones of Saul and his son from the Kedvans and buried them in the graves of his ancestors, so that God was relieved of his anger and the famine was over. (70) This amply illustrates the importance of the burial of human bodies after death; it also suggests to us that although the world of the dead as a whole does not pose a direct threat to the world of the living, in a particular case, the attitude of the living towards the dead may arouse God's attention or even intervene. Although the Jews did not try to preserve the corpses as the Egyptians did, they still did their best to perform basic embalming on the corpses, such as bathing them and applying sesame oil. The clothes worn by the deceased at burial are generally consistent with who they were before they died, and Ezekiel tells us that fallen warriors often wear armor, sword on their head pillows, and backstrings on shields when they are buried. (71) In some related tombs, clay vases and lampstands can be found; in some of the larger graves, even gold, silver, and bronze can be found. (72) This habit of using funerary objects reflects, to some extent, the Jewish understanding of life after death. According to Russ' research, around the 1st century AD, the deceased often wore their favorite costumes and ornaments, and had to dress as if they were preparing to travel; this reburial custom has caused some people of insight to rebuke, and at the end of the 1st century and the beginning of the 2nd century, Rabbi Gamaliel II brought a funeral head from Jane, and he was buried wearing only a simple birthday coat. (73) In general, the funerals of the ancient Jews were performed according to rituals and with dignity. According to Joseph, when Moses died, the people mourned for him for 30 days, which was both unprecedented and unprecedented. (74) This is tantamount to telling us that the leaders outside of Moses did not exceed Moses in terms of pomp and timing of the funeral.

Theoretically, the ancient Jews' adherence to the custom of burial seems to be related to their conception of ghosts. Due to the influence of the totality of the spirit and flesh, the Hebrews believed that the complete existence of the skeleton was the basic premise of the ghost remnants, and the dissolution of the corpse would eventually lead to the demise of the ghost. Under the domination of this concept, it is natural to choose the burial method that best maintains the integrity of the body. This inference is undoubtedly reasonable. However, judging from the actual course of history, the burial customs of ancient Jews may also have developed under the influence of some foreign races. According to Herodotus, burials were prevalent in ancient Egyptians from an early age; the ancient Babylonians adopted burial methods similar to those of the Egyptians; and in ancient Persians, burials were also prevalent, and he specifically mentioned that the Persians never cremated corpses. (75) All three peoples had historically had relatively long and direct contact with the Israelites, and it was impossible for them not to have a greater or lesser influence on the latter in their burial customs. Perhaps the real situation is that the ancient Jews' conception of the holism of the flesh and soul combined with the role of foreign cultures to promote their burial customs.

Although the ancient Jews refused to use cremation, they also often used fire during funerals. There are many examples of their funerals associated with fire. For example, the prophet Jeremiah conveyed God's word to King Zedekiah of Judah, prophesiing that he would die in peace, when many would burn incense for him, as his ancestors had been treated. (76) Another example is that after the death of King Asa of Judah, he was buried in the cliff tomb he had carved for himself in advance in the city of David, and the people smeared spices and sesame oil on his corpse and lit a huge bonfire for him. (77) Another example is the cold treatment of another king of Judah, Jolan, who died of indignation because of his inattention to God, and after which no one burned a bonfire for him, a cold reception that his ancestors had not suffered when they died. (78) The purpose of burning a bonfire, in addition to the purpose of burning incense indicated in the first example, may also include offering burnt offerings to God, which are often mentioned in the Bible; (79) or including the burning of leftover sacrifices of peace sacrifices, which the Law of Moses clearly stipulates that the sacrifices of peace cannot be eaten on the third day after the sacrifice and must be burned in their entirety; (80) In addition, such a bonfire placed next to the tomb may also include the burning of clothing that the deceased has used, according to the ancient Hebrew custom of purification, except for the funerary part, The personal belongings used by the deceased before his death cannot be used by the living, so burning them is the easiest and most reasonable way to dispose of them. The above example of the failure to enjoy the bonfire after death as a special case shows that the burning of bonfires next to the grave is a relatively common phenomenon, which can certainly not be equated with cremation. The only example of crematoria performed by the Jews in the Hebrew Bible has to do with the plight of The Father and Son of Saul. Saul and his three sons were defeated and killed, beheaded and stripped naked by the Philipstins, and their bodies were hung on the walls for public display; some Israeli warriors stole the bodies of Saul's fathers and sons, cremated them, and buried their bones. (81) Wenxing was puzzled by such a burial method that seemed to be contrary to Hebrew tradition. (82) In fact, as a general burial custom, it is only a basic principle under normal social conditions, and in some emergency periods, there should be exceptions that are tacitly acquiesced to public opinion; Saul's father and son died on the battlefield, and the restrictions of war conditions make the cremation of corpses more convenient than the burial of corpses with a set of cumbersome procedures, not to mention that the bones after burning are buried in the ground, which seems to be understood as a variation of the burial custom in emergency times. In addition, it is important to note an important detail in the incident: the heads of the four Saul fathers and sons had been cut off by the Philipstines and taken away as physical evidence of the victory over the Israelites, that is, the headsless corpses hanging from the walls of the city were actually headless corpses, and the Headless Corpses that the Israeli warriors must have stolen must have been the same, which may be the crux of the problem. Whether the israelis' cumbersome rules allowed several headless corpses insulted by the enemy to be buried according to normal procedures is highly questionable. Can the cremation and burial of them be understood as a special cleansing method for the disposal of such mutilated bodies?

Iii. The Resurrection and the Emergence of judgmental thoughts

Since Hades was merely a temporary dwelling place for the ghosts of the dead, and it did not bear any moral obligation to reward good and punish evil, there was no "afterlife" in the early Hebrew conception of an unjust present life by which all righteousness seemed to be achieved in this world, because with the strong intervention of religious collectivism and patriarchy, all righteousness seemed to be fulfilled in this world. The author of the Psalms sings in a very confident tone: "Blessed will such a person who does not follow the instigation of the wicked, who does not follow the example of sinners, who does not conform to the defilement of those who neglect God, who obeys the Law of the Lord with pleasure, and who studies it day and night... villain...... Like wheat straw blown away by the wind, sinners will be condemned by God and removed from God's people. The good will be guided and protected by the Lord, and the path taken by the wicked will lead to destruction. (83) Here, the destruction of the wicked and the blessing of the good take place in this lifetime. Moreover, due to the emphasis on family lineage and the collective responsibility of the family, retribution does not necessarily fall on individual actors, whose descendants often bear the consequences of their actions for their elders. God declared to Moses on Mount Sinai, "I am a God of compassion and mercy, not to be angry easily, and to have great love and honesty. I keep my word for millions of generations to forgive sins and transgressions, but I will punish my parents' children and grandchildren for their sins for three or four generations. (84) The consequences of the sins of ancestors were borne by their descendants, which was another major feature of the early Jewish conception of retribution.

However, as Jewish contact with foreign nations increased, foreign cultures accelerated their infiltration into Jewish society. In 333 BC, Palestine became a dependency of Alexander's Empire, and the Jews began to accept the influence of Greek culture and Hellenistic Oriental culture on a large scale. In the mid-2nd century BC, the King of the Seleucid Kingdom, Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–163 BC), imposed Hellenistic culture while banning Hebrew religious worship and customs. This act led to a great revolt led by the Maccabees in 167 BC, which led to the Jews gaining independence for a period of time until they were conquered by the Romans in 63 BC. For more than a hundred years after B.C., Hellenistic culture penetrated Jewish society at a faster rate, the most obvious sign of which was the widespread popularity of the Greek language. According to Skassogne's survey of Palestine, of the 194 tombstones belonging to the two hundred years before 135 AD, only 26 percent of the headstone inscriptions were written in Hebrew or Aramaic, while up to 64 percent were written in Greek. (85) In general, the inscriptions were read primarily by family members and friends of the deceased, which means that the Jews who were proficient in Greek at that time were no longer confined to the upper middle classes of society. Of course, the infiltration of Hellenistic culture did not ultimately lead to the complete "Hellenization" of Jewish society as a whole, but rather to the partial assimilation and absorption of these foreign cultural factors. However, the introduction of Hellenistic culture led to a historic change in Jewish society. First of all, due to the difference in attitudes towards foreign cultures, the whole society began to split into a number of opposing interest groups, such as the Sadducees with priests and nobles as the mainstay, the Pharisees with religious intellectuals as the core, and the Essenes based on the urban and rural lower classes. (86) More importantly, with the infiltration of external factors, the traditional principles of religious collectivism and patriarchy in Hebrew society are facing a serious crisis, the social ties linking individuals are gradually loosened, individualism is quietly rising, the ancient concept of justice has become weak in maintaining social morality and maintaining traditional religious beliefs, and people have begun to find that it is very unfair for children and grandchildren to bear the consequences of the actions of elders, and the present retribution that occurs to individuals rarely truly reflects the principles of social justice. Thus emerged a new conception of justice, which was inherently unconventional, because it emphasized both the idea of individual responsibility and the assumption of personal responsibility, and the pushing of the time of retribution from this life to the next.

The Book of Deuteronomy recounts the Law of Moses: "Parents should not be put to death for the sins committed by their children, nor should children be put to death for the sins committed by their parents; a man should be put to death only for the sins he has committed." (87) According to Sandmir's deduction, the Deuteronomy and other books of the Pentateuch were written between 450 and 375 BC. (88) The new ideas embodied in the above quotations could never have predated the Hellenistic era, and it is therefore clear that the text of this verse was later usurped into the Book of Deuteronomy. In any case, this passage tells us a basic message: due to the influence of Hellenistic culture, the objects of judgment and reward and punishment began to be transformed from family to individual. The prophet Jeremiah also prophesied, "When that day comes, people will never again say, 'Parents eat sour grapes, and children taste sour.' Only those who eat sour grapes will taste the sour, and everyone will die for his sins. (89) Another prophet, Ezekiel, further elaborated on this: the old proverb "When a parent eats a sour grape, a child tastes sour," it is obsolete and the sinner himself will die; if the son does evil, he will punish the son, which has nothing to do with the father; if the father does evil, he will punish the father, and it has nothing to do with the son. (90) These new ideas undoubtedly arose after the middle of the 2nd century BC with the advent of social change.

This new concept of "individual responsibility" has had a major impact not only on the secular legal adjudication system, but also on the religious and moral adjudication ideology. With the further differentiation of Hebrew society, the differences between people became more and more obvious, and the class antagonism became more and more acute. In real life, the wicked are not always punished as they deserve, the good are not necessarily protected as they deserve, and many people's moral behavior is not justly rewarded throughout their lives. Job once indignantly asked, "Why does God keep the wicked alive and make them live and prosper?" Their children and grandchildren have never quit, and they have inherited from the prime minister. God did not punish their families, and they never had to live in fear. On such questions, Job's friend Elifah, on the one hand, adhered to the traditional view that good is rewarded with good and evil with evil, and on the other hand adopted an agnostic attitude, attributing this moral problem to the mystery of God. (91) Although it is true that Job himself ended up with good deeds, this is, after all, the only example. Thus the author of Ecclesiastes later raised the same question again, (92) but he took an almost cynical attitude to deal with it: the glory and wealth of the world are empty and boring, and everything will be destroyed after death. (93)

Thus injustice in the real world is indeed a universal phenomenon, and God's justice is absolutely unquestionable; the only way to resolve this contradiction is to envisage an "afterlife" capable of centralized judgment and retribution. The emergence of the idea of the afterlife is closely related to the reversal of death. As mentioned above, the early Hebrew worldview, though with a certain concept of "life after death," existed merely as a remnant of life that would disappear with the dissolution of the corpse, that is, death was an irreversible natural process. Today, in some books of the Bible, there is a clear attempt to reverse death. The prophet Hosea relayed God's words, "Will I release them from the control of Hades?" Will I save them from death? Oh, death, your calamity is there! Oh, Hades, your destruction is there! (94) Here God makes it clear that the greatest enemy of mankind is death, but He has doubts about whether He will help mankind overcome death. However, this doubt was soon dispelled, and God's attitude became clear: "The sovereign Lord will destroy death forever!" He will wipe away everyone's tears and will remove the shame suffered by people all over the world. (95) The landmark event of this turn may have been the Babylonian captivity (587-538 BC): previously death was the inevitable outcome of every man, the king of the material world, and even God had no right to intervene; thereafter, death no longer ravaged the world, because the power of life and death began to be in the hands of God, who decided the fate of each person according to his own standards of good and evil: "God made man die and also brought man back from the dead; he made man go down to Hades and brought man back from the underworld." (96) From this was the idea of the dead and the resurrection. Whether a man can be saved is determined according to the circumstances of the judgment, so God is also the final judge of all nations, and no one can escape his judgment: "Young man... You can do whatever you want, but remember that God will judge everything you do" ;(97) "Everything you do, good or evil, even in secret, will be judged by God." (98)

The resurrection in the Hebrew Bible generally takes place after God's judgment, after which the good are resurrected, while the wicked can only atone for their sins with eternal death. However, earlier volumes of the Bible speak only vaguely of certain good men who were taken away by God, such as Enoch, who disappeared after he lived to the age of 365, "because God took him away." (99) Another example is that Elijah and Elisha were standing by the Jordan River talking, "When suddenly a fire horse came to them with a chariot of fire, and Elijah went up to heaven on a whirlwind." (100) Death, who used to see death as a ghost entering Hades, has since severed ties with God; now in these two cases, the dead man is taken away by God and taken to heaven to be with God, which cannot but be counted as a completely new factor. In a sense, ascending to the celestial realm is transcending death and thus having the character of resurrection; but the examples of being able to enjoy this special treatment are extremely rare.

However, in the later books, the resurrection is no longer seen as a privilege monopolized by the very few, and it begins to become the pursuit and expectation of many: "Many who sleep in the dust will wake up, some will live forever, and others will suffer eternal fear and shame." Wise leaders will shine with the bright sky. He who puts many on the right path will shine like the stars forever. (101) Confidence in the resurrection is evident in the book of Isaiah: "The dead will be resurrected, and their bodies will be given life again." Whoever sleeps in the grave wakes up and sings happily. Just as shining nectar renews the earth, God will resurrect those who have been dead for many years. (102) Resurrection is possible because man deserves to die: "When God created us, He did not want us to die; He made us like Himself. What brings death into the world is the jealousy of the devil, and all who belong to the devil will die. (103) In other words, since death is the work of the devil, death can be overcome if the devil is overcome, and if you want to overcome the devil and death, you must believe in God. The author of the Psalms also sings that for the rich and unmerciful, "destined to die like sheep, death is their shepherd... Their bodies decayed rapidly in Hades, and God would save me from the authority of death." (104) The "I" here stands in stark contrast to the "unmerciful for the rich": one triumphs over death and the other is enslaved to death forever, suggesting that only some people can enjoy the glory of the resurrection.

During the persecution of the Jews by the Seleucid king Antioch (c. 180-120 BC), the doctrine of resurrection gained wider acceptance among the Israelites as patriotic fervor grew. A Jewish mother was arrested along with her seven sons, and before being martyred in an extremely painful manner, six of them gave a speech about the resurrection after death. For example, when the third son was asked if he would renounce his faith, "he boldly raised his hands and bravely said, 'God has given me his hands, but for me his law is more precious than his hands, and I know that God will give these to me again.' (105) The fourth son said as death was about to come, "I am glad to die at your hands because we are sure that God will lift us out of death." But you won't be resurrected, Antioch! (106) The heroic mother also inspired each of her sons with the prospect of resurrection: "I do not know how your life began in my belly, and I am not the one who gave you life and breath and united the parts of your body." It is God who does this, god who created the universe, mankind, and all things. He is merciful, and He will give you life and breath again, for you love His law more than you love yourself. (107) These mortal Jews saw the pain of death inflicted on them by their enemies not only as a price of resurrection and eternal life, but also as a punishment from God for the sins of their people, as the sixth son said before his death, "Our suffering is deserved, because we have sinned against our God." That is why all these calamities have befallen us. ”(108)

At the same time, a certain idea of heaven, hell and retribution developed among Jewish civil society, which of course was rather hazy. Heaven is the Garden of Eden, from which Adam and Eve were cast out, and it is sometimes conceived on earth and sometimes described in heaven. According to Joseph, God built heaven somewhere in the East, a lush garden with a river that runs through the whole earth, divided into four parts: the Ganges, the Euphrates, the Tigris, and the Nile. (109) As for hell, known to the Jews as "Gehenna," it originated in southern Jerusalem, a place dedicated to human sacrifice in ancient times, a creepy place that was later placed in the depths of Hades. (110) According to the Hebrew Apocalypse literature from the end of the 3rd century BC to the early 2nd century BC, a man named Enoch, who, under the guidance of angels, went down to the mysterious land of the dead, which was at the farthest end of the earth; but by the 1st century A.D., enoch's travel destination had changed from the end of the earth to seven heavens, where heaven and hell were located. (111) It is worth noting that the Talmud literature at this time already deals with the topic of retribution after death, for example, there is a story that a rich man and a poor man died on the same day, the former having a very luxurious and dignified funeral, while the latter was only hastily buried. The poor man's friend was indignant about this, until one day he had a dream about the poor enjoying themselves in heaven and the rich suffering in hell. The friend also learned that the poor had committed sins in their lifetime, that the rich had done good deeds in their lifetimes, that the rich man's lavish funeral was a reward for his good deeds, and that the poor man's funeral was a punishment for his sins. (112) This story reveals a principle of retribution that prevailed in Jewish civil society at the time: the small sins of the good are punished in this world so that they are blessed only in another world, and the small good of the wicked is rewarded in this world so that they are punished only in the other world. The story's classification of the rich and the poor into the two diametrically opposed moral ranks of evil and good, respectively, reflects the value judgments of the lower classes and naturally cannot be seen in the Jewish upper class. Thus, even after the 2nd century BC, not all Jews believed in the resurrection and the afterlife. The Bensilla Wisdom Teachings, written around 180 B.C., (113) clearly expresses the denial of the afterlife: "A living person can sing and praise the Lord, but a dead man who has left the world cannot thank the Lord." How gracious and merciful the Lord is to those who come to the Lord! But this is not human nature, and none of us can live forever " ;(114) "God once declared death to all living things. How dare you go against the will of the Most High? In Hades, no one will ever ask you if you have lived for ten, a hundred, or a thousand years. (115) It is the Sadducees who do not believe in the resurrection and the afterlife. Joseph tells us that the Sadducees believed that the soul would disappear with the death of the body; they completely denied the existence of divine will, the idea of the soul after death, punishment and reward in the afterlife. (116) Skassone accordingly referred to the Sadducees as "Epicureans among the Jews." (117) Joseph and Skassone's claims are confirmed by the Christian New Testament. According to the Gospel of Mark, the Sadducees attacked the resurrection doctrine by using levirate, which prevailed among the Jews, and was refuted by the wisdom of Jesus. (118)

Due to the influence of the traditional spiritual-flesh holism, the resurrection of the ancient Jews was not a simple resurrection of the soul in the Greek philosophical sense, but the restoration of the body to the state of life, that is, the resurrection of the flesh. For example, the prophet Elijah resurrected the landlord's son when he was in Salefar in Sidon. It was said that the child had died of illness, and Elijah fell on top of his corpse three times, begging God to give his life back to the child, and God finally granted the prophet's request, and the child was miraculously resurrected. (119) Elisha, Elisha, elijah' student, also resurrected a child, and he first ordered his crutches to be placed in the child's face, but there was no movement, so he had to adopt Elijah's method of reviving the body by praying and massaging. (120) Shortly after Elisha's death, a corpse was thrown into Elisha's tomb in a panic, and as soon as it touched the prophet's skeleton, it was resurrected and stood up. (121) However bizarre and absurd such details of the resurrection may be, they indicate that it is the flesh that is resurrected, that is, the vitality of life that returns to the body. As for why the Jews chose the concept of bodily resurrection rather than some idea of the immortality of the soul, it is a question that cannot be fully understood for the time being. Seghor argues that although Greek thought had a certain influence on Hebrew society, when it came to the relationship between spirit and flesh, biblical writers had to adhere to the Hebrew tradition, because Greek philosophy deliberately belittled the tendency of the flesh to be at odds with the creationism of the Hebrew Bible, and in God's creation, the flesh, as an extremely important creature, should maintain its due dignity, so as to ensure consistency throughout the biblical work. (122) There is some truth to this statement. This example is enough to prove that the contact between two different cultures can lead to both mutual absorption and integration, and can also lead to mutual exclusion, making the opposition between the two more obvious, otherwise the pluralistic development of historical and real-world Chinese cannot be discussed.

In fact, the ancient Jewish view of the resurrection was not necessarily a homegrown thing. Mr. Shachid argues that the Hebrew conception of resurrection and judgment may have been borrowed from the Persian Zoroastrianism. (123) According to ancient Persian mythology, the prophet Zoroastrian would conceive a virgin and give birth to the last Savior, Saoshyans, who would resurrect all the dead and preside over the final judgment, at which time the wicked would be sent back to hell where the guilt of the flesh would be washed away; then all would cross a river of molten metal to prove the integrity of each man; and the forces of good and the forces of evil would engage in a final battle until the forces of evil were annihilated and their leader, Aliman, was destroyed (Ahriman) will never lose the ability to do evil until then. (124) This prophetic proclamation of the future coincides with the expectations of the Hebrew prophets for a restored Savior, and it can be preliminarily asserted that the former influenced the latter. However, the influence of other Near Eastern cultures cannot be ignored. As Kaufman argues, the concept of resurrection after death in the ancient Near East was mostly associated with the deification of the dead or rulers of the underworld, and was therefore considered to be intrinsically opposed to the prophetic ideals of Jewish monotheism. (125) However, if we set aside for a moment the differences in cultural systems, the influence of ancient Egypt can be strongly felt in terms of the emphasis on the resurrection of the flesh alone. It is well known that the story of Osiris, the judge of hell, was widely circulated in ancient Egypt, and the main difference in this story is that it promotes the idea of a "physical resurrection": Isis, osiris's wife, must find the body of her husband who has been chopped into pieces and scattered throughout Egypt, and sew it up with his own hands before he can be resurrected, (126) that in the eyes of the ancient Egyptians, the complete existence of the body is the basic premise of resurrection. It is clear that the Jews, who had been in such close contact with Egyptian civilization, could not remain indifferent to the basic ideas expressed in this myth. In addition, the likes of Tammuz, the babylonian god of spring creativity, and Adonis, the Phoenician god of fertility, all have some sort of resurrection capacity, and their relationship to the Jewish idea of resurrection deserves further attention.

IV. Conclusion

Through its description and repeated emphasis on tedious rituals, the Hebrew Bible not only conveys to us the basic ideas and values of the secular and religious life of the ancient Jews, but also reveals to us their basic attitudes and transcendent ways of death. Like other ancient peoples, the ancient Jews developed an extremely rich view of death, and the Hebrew culture did not lack thinking about death. Of course, special life experiences have also left a clear mark on the Jewish view of death. This tribulation nation did not deliberately fear life and death, nor did it excessively emphasize death; the god of death seemed to be more attentive to them than other important peoples of the same era, but in the face of death, they were always able to adopt a naturalistic and realistic detachment, which was closely related to their long-standing religious collectivism and family concepts. After entering the Hellenistic era, under the influence of Greek culture, individualism in Jewish society gradually prevailed, so that certain new factors, including resurrection and judgment, appeared in their conception of death. From the end of the Roman Empire, Neoplatonism began to become a new fashion in the world of thought, and the Jews who had close contact with it could not avoid profound influence. Abraham Abulafia, a famous Jewish rabbi active in the 13th century, once spoke of death in the tone of a typical Platonist: "The stronger the divine infusions in your body, the weaker your external and inner organs will become, and your flesh will begin to tremble violently until you feel that you are about to die; for your soul becomes separated from your flesh, and this separation is due to your great pleasure in regaining and knowing what you once knew." (127) Here, Abrafya, like Plato and Plotino, sees learning as a memory, understanding death as a state of soul-destroying and ecstasy in attaining the highest truth; this means that among the first-rate Jewish scholars, the traditional holism of the spiritual flesh is being shaken. However, it must be noted that, despite such a complex historical episode, the fundamental elements of the Hebrew Biblical view of death, including the understanding of the nature of death and the various customs that have formed from it, have not changed qualitatively with the passage of time, and these factors, as an important intellectual heritage of the ancient Jews, have been passed down in later historical periods and have greatly influenced later Christianity. It is no exaggeration to say that the naturalistic view of death of the ancient Jews laid the groundwork for the rise of the early Christian view of death.

exegesis:

For example, Boeus once argued that ignoring the question of death and the afterlife was an important feature of Judaism. See M.I. Boas, God, Christ and Pagan, London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1961, p.15.

Michael G.Wensing,Death and Destiny in the Bible,Collegeville:Liturgical Press,1993.

Michael Fishbane,The Kiss of God:Spiritual and Mystical Death in Judaism,Seattle & London:University of Washington Press,1994.

Neil Gillman,The Death of Death:Resurrection and Immortality in Jewish Thought,Vermont:Jewish Lights Publishing,1997.

David Kraemer,The Meanings of Death in Rabbinic Judaism,London:Routledge,2000.

Jack Riemer and Sherwin B.Nuland,eds.,Jewish Insights on Death and Mourning.New York:Syracuse University Press,2002.

C.D.Elledge,Life after Death in Early Judaism:The Evidence of Josephus,Tübingen:Mohr Siebeck,2006.

Jia Yanbin: On the Judaism View of Death, edited by Fu Youde, Jewish Studies, Vol. 7, Jinan: Shandong University Press, 2009.

The Hebrew Bible was called the "Old Testament" by later Christians. In the late 4th century AD, the Latin godfather Jerome, after a long period of collection, compilation and translation, eventually formed a popular Latin version of the Bible, the famous Vulgate Bible. The Old Testament part of this edition of the Bible, although based primarily on the ancient Hebrew version, also incorporates the contents and elements of other different texts, including the Septuagint Greek translation, so that from the point of view of cultural connotations, this version contains undoubtedly the richest cultural and historical information than the various other versions that were popular before, contemporaneously, and for a considerable period of time to come; as far as Old Testament thought is concerned, it not only reflects the situation of ancient Jewish society in the more primitive state before the Magabi Rebellion. It also reflects the impact and influence of foreign cultures (especially Hellenistic cultures) on the Jewish community since then. In other words, the Old Testament section of the Popular Latin Bible contains both orthodox and unorthodox ideas and views among Jews, so this version best reflects the origin, inheritance, development, evolution, and relationship of the Jewish historical tradition with the surrounding foreign cultures. The Biblia Sacra (iuxta vulgatam versionem, Stuttgart: Deutsche Bilelgesellschaft, 1994) used in this article is a synthesis of multiple exotic elements popular in the Western Church in the Middle and Modern Periods, based on the Jerome version, and its richness has greatly exceeded Jerome's version, since its inception. Its academic value has been widely recognized by the academic community. This is the main reason why this article uses it as a core document.

Given the logical confusion of the story of creation in Genesis, there is every reason to believe that the story is nothing more than a mixture of works by several different authors. See Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? New York:Harper Collins Publishers,1987.

(11) Liber Genesis, 1:26-27.The biblical version used in this article is Biblia Sacra, and the titles and names of the people involved are translated according to Protestant custom. The following quotations are indicated only by the title and chapter, without further attribution of the version.

(12) Free Genesis,2:7-22.

(13) Jacques Choron,Death and Western Thought,New York & London:The Macmillan Company & Collier-Macmillan,Ltd.,1963,p.81.

(14) Free Genesis,2:15-17.

(15) Free Genesis,3:1-7.

(16) Liber Sapientiae, 1:13–14.

(17) Saint Augustine,City of God,Book XII,Chapter 22,San Francisco:Penguin Books Ltd.,1984.

(48) Free Genesis,5:3-11.

(19) Free Genesis,9:29.

(20) Free Genesis,11:10-25.

(21) Free Genesis,25:7-8; 23:1.

(22) Free Genesis,35:28.

(23) Free Genesis,47:28.

(24) Free Deuteronomy,34:7.

(25) Free Joshua,24:29.

(26) I Samuhelis,4:15.

(27) Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,trans,by William Whiston,vol.1,Book I,Chapter 3,Philadelphia:Jas.B.Smith & Co.,1854,p.45.

(28) Oskar Skarsaune,In the Shadow of the Temple:Jewish Influences on Early Christianity,Downers Grove:InterVarsity Press,2002,p.95.

(29) Liber Iob,34:14-15.

(30) Psalmorum,103:29.

(31) Free Genesis,3:19.

(32) Liber Iesu Filii Sirach, 41:5.

(33) II Samuhelis,14:14.

(34) Free Genesis,15:15.

(35) Liber Iob.5:26.

(36) Psalmorum,89:14.

(37) Free Deuteronomy,30:15-16.

(38) Jack Riemer and Sherwin B.Nuland,eds.,Jewish Insights on Death and Mourning,p.7.

(39) Free Genesis,47:29-30.

(40) Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.1,Book II,Chapter 8,p.81.

(41) III Regum,2:10; 11:43; IV Regum,14:16; II Paralipomenon,16:13-14.

(42) See Liber Iudicum, 8:32; 16:31; II Samuhelis,2:32; 17:23.

(43) Michael G.Wensing,Deathand Destiny in the Bible,p.36.

(44) Free Genesis,22:17-18.

(45) Liber Iob,5:25.

(46) Liber Iesu Filii Sirach,41:1-4.

(47) Ill Regum,19:4.

(48) Liber Iob,7:16.

(49) Iona Propheta,4:3.

(50) Isaias Propheta,38:1-8.

(51)参见Philip Babcock Gove,ed.,Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged,Springfield:Merriam-Webster Inc.,1961,p.2093.

(52) Liber Iob,26:5-6.

(53) Isaias Propheta,14:9,11.

(54) Eliezer Segal,"Judaism," in Harold Coward,ed.,Life after Death in World Religions,New York:Orbis Books,1997,p.14.

(55) Hiezechiel Propheta,32:19-23.

(56) Psalmorum,87:4-7.

(57) When he decided to forgive his descendants because of his piety, God said, "People have evil thoughts from an early age. Thus, for at least one biblical writer, man has some sinful nature. See Liber Genesis, 8:21.

(58) Psalmorum,6:6.

(59) Psalmorum,30:13.

(60) Psalmorum,113:25.

(61) Psalmorum,87:12-13.

(62) Free Baruch,2:17.

(63) Isaias Propheta,38:18-19.

(64) I Samuhelis,28:3-19.

(65)"The Martyrdom of Pionius the Presbyter and His Companions," in The Acts of the Christian Martyrs,Introduction,trans. Herbert Musurillo,Oxford:The Clarendon Press,1972,p.155.

(66) I Samuhelis,28:14.

(67) Eliezer Segal,"Judaism," p.15.

(68) We do not have complete information from the Bible about the handling of the funerals of the early Jews, but Remolel's investigation of the funerals of contemporary American Jews provides us with valuable references, including visits to the dying; sorting out the bodies; caring for the corpses (Shomer); funeral rites; tearing robes and crying; singing hymns to the dead; observing the eleven-month period of mourning (Shloshim); praying in prayer groups (Minyan) ; anniversary ceremony (Yahrzet), etc. See Jack Riemer and Sherwin B.Nuland,eds.,Jewish Insights on Death and Mourning,Foreword,p.xvi.

(69) Free Levitici,20:14.

(70) II Samuhelis,21:1-14.

(71) Hiezechiel Propheta,32:27.

(72) Michael G.Wensing,Death and Destiny in the Bible,pp.39-40.

(73) Alfred C.Rush,Death and Burial in Christian Antiquity,Washington,D.C.:The Catholic University of America Press,1941,p.128.

(74) Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.1,Book IV,Chapter 8,p.147.

(75) Herodotus,The Histories,trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt,Book 2,Harmondsworth:Penguin Books Ltd.,1964,pp.132-134; Book 1,p.94; Book 3,pp.180-181.

(76) Hieremias Prophetae,34:1-5.

(77) IV Regum,16:11-14.

(78) II Paralipomenon,21:18-20.

(79) Free Levitici,21:6.

(80) Free of Levitia,19:5-7.

(81) I Samuhelis,31:1-13.

(82) Michael G.Wensing,Death and Destiny in the Bible,p.39.

(83) Psalmorum,1:1-6.

(84) Free Exodi,34:6-7.

(85) Oskar Skarsaune,In the Shadow of the Temple:Jewish Influences on Early Christianity,p.41.

(86)参见Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.2,Book XVIII,Chapter 1,p.66.

(87) Free Deuteronomy,24:16.

(88) Samuel Sandmel,Judaism and Christian Beginnings,New York:Oxford University Press,1978,p.24.

(89) Hieremias Prophetae,31:29-30.

(90) Hiezechiel Propheta,18:1-4; 10-20.

(91) Liber Iob,21:7-9; 22:13-20; 4:7-8.

(92) Liber Ecclesiastes,9:2-10.

(93) Liber Ecclesiastes,6:1-11; 9:2-10.

(94) Osee Propheta,13:14.

(95) Isaias Propheta, 25:8.

(96) I Samuhelis,2:6.

(97) Liber Ecclesiastes,11:9.

(98) Liber Ecclesiastes,12:14.

(99) Free Genesis,5:23-24.

(100) IV Regum,2:11.

(101) Danihel Propheta,12:2-3.

(102) Isaias Propheta,26:19.

(103) Liber Sapientiae,2:23-24.

(104) Psalmorum,48:15-16.

(105) Liber II Macchabeorum,7:10-11.

(106) Liber II Macchabeorum,7:14.

(107) Liber II Macchabeorum,7:22-23.

(108) Liber II Macchabeorum, 7:18. For an ancient Jewish understanding of their own sin, see Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? pp.138-140.

(109) Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews, in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.1.Book I,Chapter 1,p.41.

(110) Eliezer Segal,"Judaism," p.22.

(111) Richard Bauckham,The Fate of the Dead:Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses,Leiden,Boston and Koln:Brill,1998,pp.83-88.

(112) Richard Bauckham,The Fate of the Dead:Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses,p.99.

(113)参见Samuel Sandmel,Judaism and Christian Beginnings,p.77.

(114) Liber Iesu Filii Sirach, 17:28-30.

(115) Liber Iesu Filii Sirach, 41:5-6.

(106) Flavius Josephus,The Antiquities of the Jews,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.2,Book XVIII,Chapter 1,p.66; Flavius Josephus,A History of the Jewish Wars,in The Works of Flavius Josephus,vol.2,Book II,Chapter 8,p.216.

(117) Oskar Skarsaune,In the Shadow of the Temple:Jewish Influences on Early Christianity,p.110.

(118) See Schundum Marcum, 12:18-27.Levirate is a marriage custom widely popular among the ancient Hebrews, according to which a wife must marry a brother or other close relative of the deceased husband if he has no descendants after his death. According to the Gospel of Mark, the Sadducees asked Jesus: There are seven brothers, the eldest died childless, and his wife married the second; the second died without children, so he married the third; so he married the seventh; and finally the woman died without children; if there is a resurrection, which of the seven women should be the wife of the seven? Jesus replied: The resurrected man is like an angel, and there is no marriage, so there is no dispute over belonging.

(119) III Regum,17:17-24.

(120) IV Regum,4:18-37.

(121) IV Regum,13:20-21.

(122) Eliezer Segal,"Judaism," p.18.

(123) Shaul Shaked,"Iranian Influence on Judaism," in W.D.Davies and Louis Finkelstein,eds.,The Cambridge History of Judaism,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1984,pp.323-324.

(124) J.R.Hinnells,"Zoroastrianism," in Richard Cavendish,ed.,Mythology:An Illustrated Encyclopedia,London:Orbis Publishing Limited,1980,p.42.

(125) See Eliezer Segal, "Judaism," pp.15-16.

(126) Bruce Lafontaine,Gods of Ancient Egypt,no.3,New York:Dover Publications,Inc.,2002.

(127) Michael Fishbane,The Kiss of God:Spiritual and Mystical Death in Judaism,pp.39-40.