On October 10, 732, a group of Berber (nomadic herders from Africa) scouts were jogging their horses through the barren farmland outside Tours (present-day midwestern French cities), each wrapped themselves in several thick layers of robes. Despite being away from their leader, the Spanish governor of the Umayyad dynasty, Abdel Rahman (?). –732) – Having led them across the Pyrenees for months, the spoils of war that had belonged to the Franks had given the army the impetus to move forward in several battles and raids, but the cold winters of Western Europe were unseen by these desert visitors. It seemed that the weak, trembling Christians of Tours and their treasures had become less attractive in the face of the wind and snow. Suddenly, the distant scene made the scouts strangle their horses. On the horizon, the flickering spear tips, the reflection of the chainmail, the footsteps that shook the earth, and the dust flew all made them realize one thing: the Frankish army was coming.

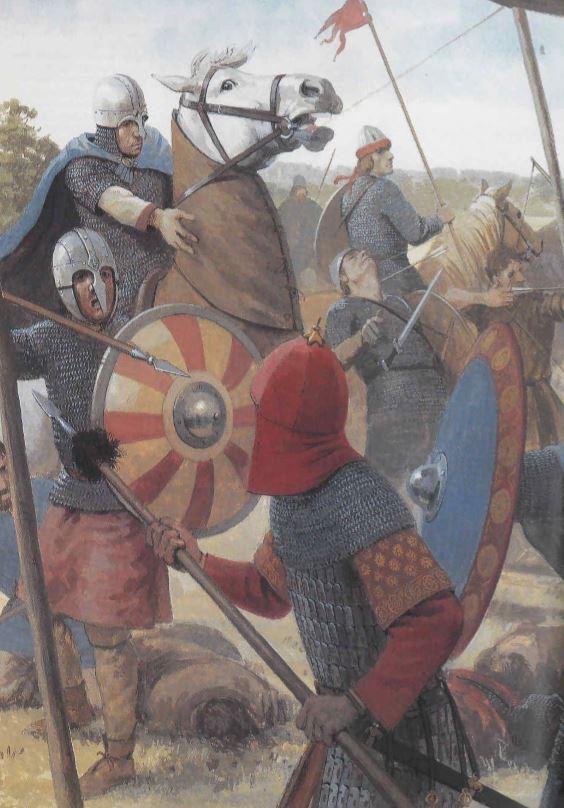

Frankish and Umayyad armies engaged in the Battle of Tours

Leading this army was the Frankish palace minister, Duke Charles (686-741). After receiving the news of the Umayyad invasion, he gathered his army as quickly as possible and rushed to the south. At the same time, Abdul Rahman learned of the arrival of the Frankish army and set up his camp to fight. A battle to determine the fate of the Frankish kingdom, and indeed the entire Christian world of Western Europe, began.

At first, the two sides were almost on an equal footing, with the Umayyad cavalry repeatedly charging the Frankish front, while the Franks drew up strong shield walls to resist. The form then began to reverse, and chronicles of the time recorded that the Frankish warriors were "as untouchable as the sea." They stood firmly, one against the other, forming fortresses like ice cubes" and "tirelessly swinging their swords into the chest of their enemies", and in the face of the indestructible position, the Umayyad cavalry gradually came to an inferior position. At this time, the news of Charles's sneak attack on the camp led by charles completely destroyed the morale of the Umayyad army, Abdul Rahman was also killed in the retreat, and the Franks achieved a brilliant victory. This is the most famous example of the early Frankish army coming to the fore on the battlefield.

"Hammer" Charlie confronts Abdul Rahman

In the middle of the eighth century, a series of changes took place within the once mighty Frankish kingdom. Pepin the "dwarf" (714-768, the son of Duke Charles above), who had been the palace minister of the Merovin dynasty, replaced the last Merovingian king and established the new Carolingian dynasty. (For an introduction to the position of palace minister and Carolingian's usurpation of the throne, please refer to another article of mine: Why can the "palace ministers" in France have the power to turn to the opposition, and how can they compare with the ancient prime ministers of our country?) His son Charlemagne (742-814), on the other hand, unified all of Western Europe with steel and crosses, and on Christmas Day 800 he was crowned "Emperor of the Romans" by the Pope, taking over the centuries-old French rule of the Western Roman Empire, which later generations called the "Carolingian Empire."

Charlemagne's Empire

Because the Franks were born into the once barbaric Germanic tribes, for them military achievements were more dazzling than their achievements in all aspects. This article will briefly introduce the composition and tactics of the Carolingian army, so that everyone can have a basic understanding of the army that accompanied Charlemagne in his conquest of Europe.

· Composition of the army

The composition of the Carolingian army can be divided into two main categories: the main army composed of franks in the country, and the auxiliary corps from the allies, tributary states, and vassal states.

The smallest and most elite of the country's armies is "scara," which means "sacred" in Latin. They were an army formed during the reign of Pepin, and they were highly skilled in martial arts, and could either immediately attack the enemy army or fight in a column of horses. During the Charlemagne period, he was mostly used as a royal guard and was directly under the command of the king. In the 11th-century epic "The Song of Roland", the paladin Roland's prototype in reality must be a Scala guard. In addition, the proportion of other noble cavalry in the Frankish army of Charlemagne's time was also increasing, which was very different from the Merovingian army, which had an absolute majority of infantry in the early days.

The picture shows scola, a high-ranking Scala officer

In addition to these professional soldiers, the absolute main force of the Frankish army consisted of conscripts. Unlike professional soldiers, who were also trained in peacetime, conscripts were only called to the battlefield when war broke out to form infantry. This form of conscription, known as the lantweri, was strictly regulated by statute on the management and recruitment of conscripts. The Edict of Italy of 801 states: "Any free man who despises my orders and refuses to call ... According to the Frankish law, a fine of sixty Sorridas will be paid. Another is: "Anyone who flouts the king's law, without the king's permission, leaves the army without permission and returns home on his own... The death penalty was due and the property was deposited in the State Treasury. The conscripts were less equipped and disciplined than professionals, but it was with these large numbers of "cannon fodder" that the frontal front of the Carolingian army was maintained.

Recruit soldiers and lead their nobles

On the other hand, the Frankish army also had a large number of foreign soldiers from Burgundy, Bavaria, Provence, Brittany and Lombardy, who fought in their homeland and were usually assigned to where they were needed on the battlefield. For example, the Brittans and Lombards would join the Frankish cavalry in storming the enemy front, while the Aquitaines and the Goths from Iberia, who were good at guerrilla warfare, would act as scattered soldiers, luring the enemy to attack or harassing the enemy in the rear.

Gasconian cavalry and Scala's guards fighting side by side

· Tactics and armament

Since stirrups were not yet widespread in the early Middle Ages, the Carolingian "heavy cavalry" played a different role than the byzantine men's armored heavy cavalry. Equipped with simple chainmails, spears, and spears, their tactics were mostly based on raiding enemy weaknesses rather than charging head-on. During combat, the cavalry was divided into 50-100 formations called "cunei" (cunei), which coordinated with their own troops to attack the enemy's flanks. The conscripted infantry, which was the main force, formed a large and dense phalanx, under the command of trumpets and flags, and pressed against the enemy.

Flags used by cavalry

Usually, such a "Frankish" attack would quickly overwhelm any young man who dared to resist Charlemagne, but in order to face the fast and agile Magyar cavalry from the east, the Frankish army also began to develop its own archers and mounted archers. These Frankish archers generally used hyperbolic composite bows derived from the Roman period, and in the late period, they mostly used light and flexible short bows. The auxiliary armies in the Allemani region used purple-shirted wood and powerful longbows as their main weapons, more than four hundred years earlier than the longbow legions established by the Later English. The equipment of mounted archers was not much different from that of archers, but in order to cooperate with the overall action of the army, they usually dismounted and fought, which is quite similar to the "dragoons" in European armies in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Magyar people

Looking at the carolingian army in general, it is not difficult to find that it bears some resemblance to the composition of the legions at the height of the Roman Empire. Not only do they also have a fresh force dominated by their own nationalities, but the multi-ethnic auxiliary forces under their rule also provide a wealth of tactical options for facing a variety of enemies. It was with this powerful army that Charlemagne was able to bring the whole of Europe under his feet. But in the middle of the ninth century, the rise of the Vikings posed a serious threat to the Franks. The large and bloated army could not effectively counter the Viking longships, and their "grab and run" maneuverability at sea was not something the Franks, whose navy had not yet formed an organization, could deal with. Coupled with the struggle for power and the outbreak of civil war by the descendants of the Carolingian clan, the sword forged by Pepin and Charlemagne finally shattered, until it was reforged by the modern monarchs who had gathered royal power, and it could continue to shine on the stage of history.