"The great affairs of the country are in the worship and the rong." The phrase "Zuo Biao" is confirmed in the Mediterranean Sea, thousands of miles away. In 49 BC, on the Rubicon River in northern Italy, a man over half a hundred years old led a large army across the river, leaving the famous phrase "The dice have been thrown down", which means that the war has begun and the bet on fate has begun.

Since there have been written records, the 6,000-year history of human civilization is undoubtedly a history of war, and the victory or defeat of war often determines the survival of tribal city-states and even the rise and fall of national civilization. As Sun Wu, the ancient Chinese "soldier saint", said: "Soldiers, the great affairs of the country, the place of death and life, the way of survival, must not be unaware." ”

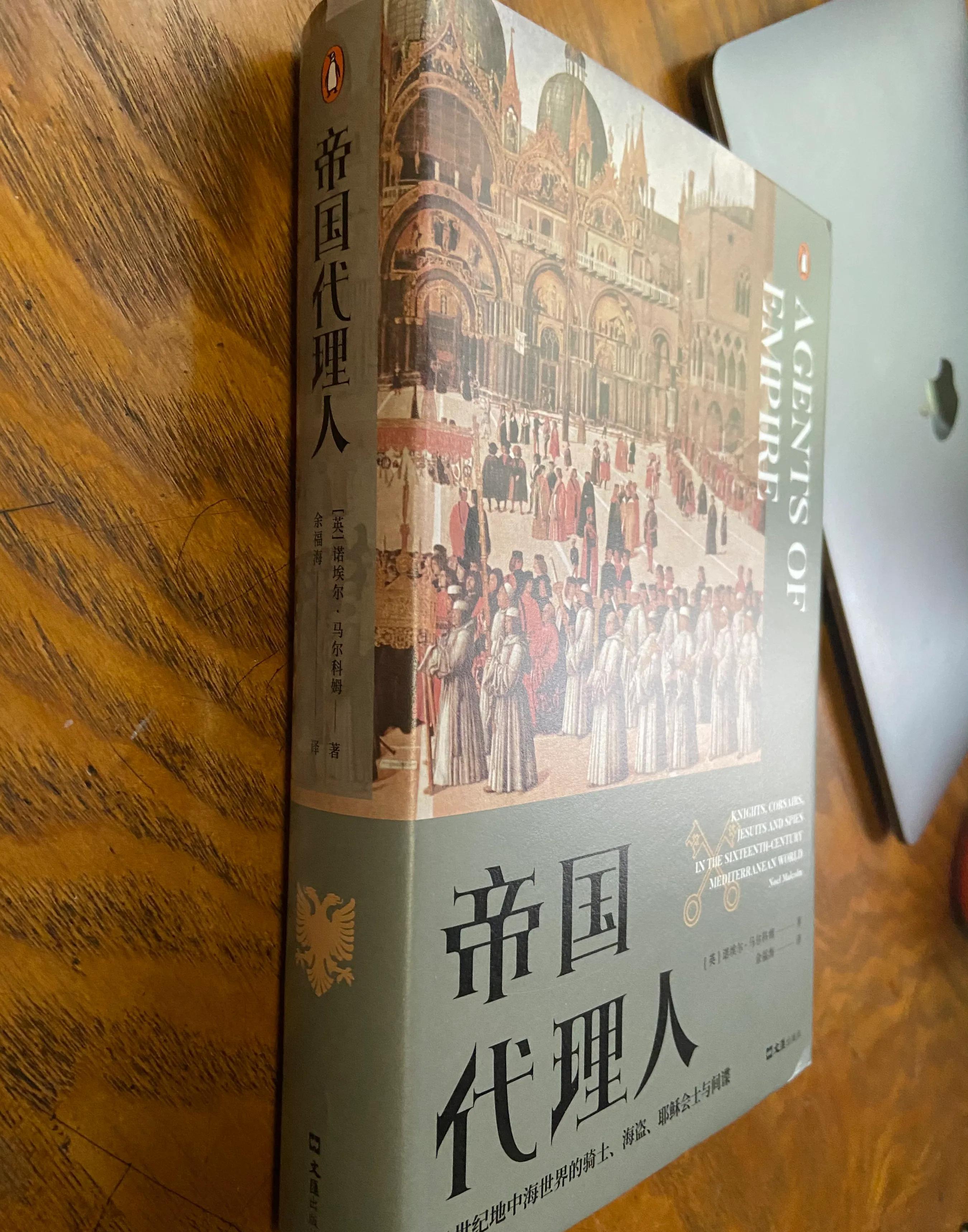

The Mediterranean region, the cradle of Western civilization, has been in flames and wars since the 16th century. Sir Noel Malcolm, a contemporary British historian and senior fellow at the Universal College of Oxford University, recently wrote the book "Agents of the Empire: Knights, Pirates, Jesuits and Spies of the Mediterranean World in the 16th Century", which continues his usual vivid and simple style of writing, and breaks new ground, outlining the history of the Ottoman Empire and the Venetian war from the perspective of "microhistory", as well as the communication between the two families of Bruni and Bruti before and after the war, with their outstanding foreign language ability and long-sleeved good dance. For more than half a century, the title of "Agent of the Empire" was contested.

Although both families have suffered heavy losses and paid a terrible price in the process, they are still envious of a world that is "full of cross-border ties, and trust between private individuals can easily trump official hostility". From this, Malcolm pondered the many connections and problems that exist between history and the present, between the West and the world. When I first read this book, I felt refreshed; when I read it carefully, I felt that the aftertaste was endless.

From the perspective of macro development, although the big history, big events, big countries, big people, and big times are the totem of the entire Mediterranean history, those who are ignored by the main theme of history are also a crucial factor that is very likely to cause the situation at that time or to promote the historical process. The best of them are like the souls of Agents of the Empire, the Bruni and Bruttis. They have come and gone for their own good, but so far no one has ever told us their story.

At that time, Albania was mixed between the Ottoman and Venetian empires, although it was bullied, but the best of the best could still navigate the cracks. Such as a Catholic archbishop of the Brüni family, a knighted captain at the Battle of Lepanto, a high-ranking spy interpreter with free access to the imperial court, and the unpopular Jesuit and Maltese knight Gasparo Bruni. At the same time, his in-laws, the Bruti family, performed equally well, and the peak of their family's glory was the cultivation of Antonio, who was first knighted for his outstanding service in securing the food supply of the empire, and then was made a nobleman by a special decree of the Doge of Venice. Brutty. Later, the marriage between the two families further increased their influence and control over the local political and economic landscape.

With the rise and fall of the two great families and their illustrious figures at the core, as knights, pirates, Jesuits and spies who were active between the Mediterranean countries and important cities in the 16th century came to the historical stage, the book highlights the hegemonic struggle between Venice and the Ottoman Empire in the Adriatic Sea and the eastern Mediterranean in the late sixteenth century, as well as the subtle psychological activities of ordinary people who could change religion at any time in order to maintain basic survival in that special era, and their social production and life scenes.

As a fan of military warfare, I am deeply concerned about the eighth chapter of this book, and the author devotes an entire chapter to the defeat at the Battle of Lepanto by the Christian Coalition. The fierce naval battle, in Western historical records, in which "shelling on all sides was like thunder, and the noble fleet was shrouded in thick smoke from the sky" was recognized as a sign of the decline of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, and the wrath of the allies who were eager for revenge after the fall of Cyprus, especially the Venetians. It was in this naval battle that One of the book's souls, Gasparro Bruni, came to great lengths, not only as a combat commander for sailors and crews, but also as a pioneer himself, and was seriously wounded in the battle.

In addition, in addition to the love-hate relationship between Albania and the Ottoman Empire and Venice throughout the book, it is also important to ignore that in the 16th century, neither the Ottoman Empire nor the powerful Spain had a mediterranean core interest. Nevertheless, the Mediterranean region remains an important node in the expansion of the two countries. As Malcolm stated, the Ottoman Empire's policy of piracy basically fulfilled its intended goal, successfully resisting Spain's expansion into North Africa, and on this basis dealt a heavy blow to the Christian countries, which in turn caused the Christian countries to fight back. The Ottoman Empire supported North African pirates in their fight against Spanish influence in the Mediterranean, and Spain funded the Knights to fight against muslim incursions.

It is clear that the struggle for supremacy between the Ottoman Empire and the Spanish Empire over the Mediterranean Sea was also mainly about proxy wars. Proxy warfare was the best option for two empires to adopt when they were equal in power. In the course of the struggle in the Mediterranean, all participants enshrined the principle of self-interest as the only criterion, and religious and cultural factors were completely subordinated to the principle of self-interest. So, in every respect, the imperial proxy wars of the Mediterranean in the 16th century are a glimpse into the modern Mediterranean struggle for supremacy!