He Jun

For the author's generation, it seems that in the blink of an eye, the new century has passed 20 years. Just 20 years ago, in December 1999, Time magazine looked back on the entire 20th century and selected "Person of the Century", elected by the scientist, thinker and social activist Albert Einstein. It had been nearly half a century since his death. In the new century, however, the brilliance of this celebrity has not faded: the in-depth study of his scientific achievements and ideas, life, and social and political activities continues to be an important topic in the field of scientific history; a series of new scientific achievements in fields such as gravitational waves and quantum communications and related to him continue to stimulate new public interest; in 2019, the scientific community in China and the world has just experienced a series of commemorations of the 140th anniversary of Einstein's birth The editing of Einstein's complete works, which began in 1987 at Princeton University in the United States, has published 14 volumes by 2015, less than half of the expected total, while in 2012 it was 13 volumes, of which the translation can be said to be long overdue.

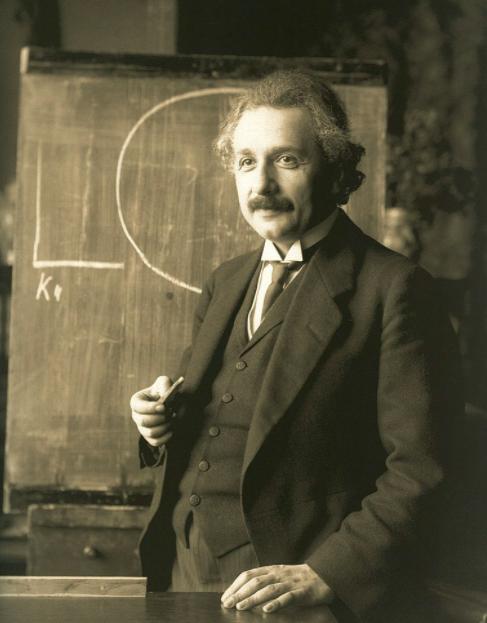

Einstein

The Complete Works of Einstein, Volume 13 covers the period from January 1922 to March 1923, when Germany was in the turbulent and difficult period of the Weimar Republic after World War I. At this time, Einstein, with the establishment of general relativity, had become a world-famous public figure and actively participated in social and political activities. During this period, he spent almost half of his time outside Of Germany, so the book also presents a scene of the era in the wider international community. From this volume onwards, articles and correspondence are no longer published in separate volumes, but are arranged together in chronological order, which is conducive to readers to better restore and understand the historical context in which the master's science, social activities, and private life are intertwined.

One. Science and technology

We'll start with scientific topics and introduce some of the important elements of this book.

Einstein was often invited to give lectures, questions and answers to the public and the scientific community, and to write critical texts. These texts, without exception, embody the distinct Einstein style, that is, starting from seemingly simple and basic concepts, with deep insight and meticulous thinking, revealing the profound meaning and connection behind them. This part alone is of great reading value, especially around the dissemination, debate, and philosophical significance of the theory of relativity. During a visit to Japan, Einstein also improvised questions and answers about his discovery of relativity. This book provides an up-to-date interpretation of this important document in the history of science.

It was also in this year that Einstein was hinted at by the Swedish side that he would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics the year before, preferably staying in Europe at the end of the year in order to be able to attend the prize. However, he decided to continue to arrange his trip to Japan. Einstein's delay in winning the Norbert Prize has become an embarrassment for both himself and the Nobel Committee. This is due to the controversy surrounding his contributions to relativity, especially in Northern Europe (and in a sense, Germany) that focuses on the tradition of experimental physics. On his way to the Far East, he finally received an award-winning telegram, but the reason given was in recognition of his theory of the photoelectric effect.

As far as cutting-edge scientific research is concerned, there is a view that after the creation of general relativity in 1915, Einstein never had a creation comparable to his previous achievements. In this volume, the reader can see some specific research and thinking processes of this scientific giant and form his own understanding. In early 1921, Einstein began to devote considerable energy to a very fundamental topic in quantum theory, that is, whether the process of radiation of a single atom is continuous radiation in accordance with classical wave theory, or instantaneous monochromatic quantum emission according to quantum theory. By the beginning of 1922, he considered himself to have achieved important results, of which was self-evident, no less than any of his earlier works. In this volume, readers can see the shock and confusion and reserved "congratulations" of some of his peers, as well as the persuasion of Ehrenfest to pull the bull's head, and the blunt criticism of Lauer, who has poor interpersonal skills, and Einstein did not feel offended in the slightest. The friendship with Ehrenfest runs through all volumes of Einstein's complete works, and this volume is no exception. One basis of friendship that the reader can see is the latter's highly insightful and witty and intuitive expression of physical concepts similar to that of Einstein himself. Presenting the original process of Einstein's scientific exploration, including twists and turns and failures, is an important contribution of the complete series to the study of the history of science. Although the research that I had greatly expected during this period did not achieve the expected results, it showed that Einstein, after years of success in single-handedly proposing and promoting the concept of wave-particle duality of light, did not think that this was the ultimate understanding in his heart. Other work on quantum theory in this volume includes the idea of the Stark effect, a theoretical explanation of the Stern-Gelach experiment, and a theory of superconductivity. Although his exploration of superconductivity theory is preliminary and has not achieved any success, professional readers should be able to see Einstein's profound thinking on the theory of matter and the nature of quantum (including the problem of zero-point energy) from the original exploration process.

In addition to the field of quantum theory that he attached great importance to, Einstein also devoted himself to the cosmological application of general relativity during this period, and made a pioneering attempt at the unified field theory of general relativity and electromagnetism. In particular, this volume provides some procedural literature on the latter. These areas have even become a hot topic of popular science recently. In academic discussions during his trip to Paris, he and his colleagues have spoken about many of the features of what is now called black holes, although the concept will not be concretely formed until nearly half a century later. From all these documents, the reader may feel that, at least at this time, Einstein, who has reached middle age, has not tended to exhaust his personal scientific creativity; on the contrary, the new themes, directions, and new fields he has created with keen insight are extremely grand and difficult, requiring the unremitting efforts of generations of outstanding scholars for a hundred years to accumulate more experimental results and theoretical construction, which has not yet been completely clarified.

In Einstein's correspondence with his peers, one can also see the scientific thinking, creation, and discussion of other outstanding scholars. For example, Born's report on his progress in crystal theory, perturbation theory, and quantum chemistry, as well as Debye's own debate on the theory of intermolecular forces, all involve the core contributions of relevant scholars to science, and are undoubtedly important historical materials for science.

In addition to these core problems in theoretical physics, Einstein also maintained a keen interest in practical techniques, as reflected in some of the documents on patents in this book. During the stormy and dangerous times, he even considered and arranged to leave Berlin and academia to go to Kiel's industrialist friends to develop practical technologies. The reasons behind this, in addition to commercial interests and early work at the Bern Patent Office, are also his Einstein curiosity about technology itself, as well as the imprint of the era of the encyclopedic scholar.

Two. The political turmoil of the times

In addition to the scientific field, this volume also contains more content of social and political activities, which not only reflects another focus of the life of the master, but also immerses the reader in the strong atmosphere of the times. The Weimar Republic, established on the ruins of the collapse of the German Empire after the war, was in internal and external difficulties, facing huge war reparations, a bloody economy, inflation, soaring prices, and the misery of popular life; left-right antagonism, the rampant spread of far-right forces, and the country faced unknown risks and choices of path. All of this is shown in the words of this volume. The hard times have not left any scholar with an academic ivory tower in which to settle. Resisting pressure from both sides, Einstein resolutely accepted the meticulous arrangements of Lang Zhiwan and others, and embarked on an ice-breaking trip to Paris, taking an important step towards the post-war international reconciliation between the two sworn enemies of Germany and France. Together with Marie Curie and others, he joined the International Council for Intellectual Cooperation under the League of Nations to work for world peace. Einstein used his influence among the people abroad to rescue German intellectual workers in poverty and hunger, and at the same time used his high-level political connections abroad in an attempt to help reduce the burden on the country and win a little breathing space and hope for the German economy. During this period, Einstein left behind a number of famous texts, including The Internationality of Science and the Preface to the German Edition of Russell's Political Ideals. In this book, readers can read about his like-mindedness and bile-likeness with Marie Curie, Lang Zhiwan and others, as well as correspondence with other progressives.

The Complete Works of Einstein (Volume XIII)

But the most important event for him during this period was his friend, the assassination of walter Ratnau, the foreign minister of the Weimar Republic, by right-wing extremists, which aroused the indignation of the broad masses and made the right-wing forces more tyrannical and arrogant, and the country was on the verge of civil war. This major event in the history of the Weimar Republic was also a turning point in Einstein's life, leaving a considerable number of relevant documents in this volume. In one of the published eulogies, Einstein wrote a widely praised quote: "It is not difficult for a man who is obsessed with fantasies to become an idealist; rattenau is an idealist who has entered the world, who is far more insightful than ordinary people." "Einstein realized that, as a prominent Jewish leftist in German public life, his personal safety was already under threat. This became one of the reasons why he accepted an invitation from the Far East to leave Germany temporarily. Perhaps from this time on, the seeds of a final break with Germany had been sown.

Three. A trip to the Far East

A trip to the Far East, which lasted more than five months from the end of 1922 to the beginning of 1923, is an important part of this volume. Japan, the main target of Einstein's visit, was in the midst of the progressive trend of secularism and democratization in the Taisho era, experiencing rapid ideological changes, and internationalism and cosmopolitanism constantly attacked narrow traditional concepts. This is the political background and material basis of the era on which the Japanese "Reform Society" was invited to go on a trip, and Einstein's observations and reflections on the level of material productivity and class relations are also seen in the diary. But here we focus on its cultural side, because the long travel diary, which is first published in this book, has been translated into many languages, causing a lot of attention, research, controversy, and some even outrage, especially about the Chinese. Chinese readers can also refer to the relevant content and comments compiled by Professor Shi Yu of the Department of Physics of Fudan University.

Einstein's second trip to Asia, shortly after his first visit to the United States from the European continent in 1921, was a rare opportunity and event in an era when the time, cost, inconvenience, and risk of such a trans-ocean trip could not be compared to today. Although the last trip to the United States was for a cause he wholeheartedly supported, one can also feel that Einstein, like ordinary people, has developed a great deal of interest in overseas travel after that. I have made a lot of preparations for this trip, with a lot of expectations, and my mood is more relaxed, although the travel diary is concise, it is rich in content and vividly depicts the natural landscape of sea rain and rain, water and land, and the continuous mountain islands, as well as various fireworks and people's habits, gathering and dispersing, and exotic humanistic customs. The more important of these, however, is the impact of culture. Einstein's travel diary was not intended for any outsider to read, so it more freely reflected his inner spiritual world. The reader can see the author's strong European cultural consciousness, but perhaps because of his consistent progressiveness and the situation in Europe itself, he is not condescending and arrogant, but with an equal heart, he always strives to observe and record the culture of others and compare it with himself. As the destination of this long trip, despite the exhausting arrangements and the embarrassment of unavoidable unexpected culture shock, Japan undoubtedly left a good impression on Einstein, making him not stingy with heartfelt words of praise in his diaries and letters. Along the way, the most negative descriptions are undoubtedly left to the Chinese near Hong Kong and Shanghai: although he has respect for Chinese cultural traditions, the dirty and unhygienic street environment, the pawns of the peddlers who struggle to make a living, and the courteous and wealthy gentry who are vassals have not won Einstein's favor. What's more, he used the meanness and insidiousness of European humor to ridicule Chinese women. This makes the defenses that encapsulate their impression of China in terms of "lamenting their misfortunes" seem somewhat reluctant, although Einstein was also frankly critical of Europeans and culture, although he did not deny that there was a vulgar side of his sense of humor, and although in the subsequent anti-fascist war he unreservedly supported China's resistance to Japanese militarist aggression. Readers can also see from this book document how Einstein lost his hand with the visit to Peking University, and lamented the helplessness and misfortune of the Chinese nation during the period when the warlords and the people were not talking about their lives.

The return visit to Palestine was also the focus of the trip. The lines of the diary show once again that Einstein's support for Zionism was primarily support for the oppressed peoples as a progressive european culture, rather than out of his own Jewish identity. His public emphasis on his Jewish identity was merely an expression of his disdain for the "assimilation" tactics of downplaying or even concealing his Jewish identity in order to rush into mainstream society. In Palestine, which Einstein wholeheartedly and vehemently supported, he was more concerned with attempts to build an ideal society for the left.

We know that Einstein was rated by Western readers as the great man of the century, not simply for his scientific contributions. In a sense, it can even be said that his scientific contributions are mainly to provide an opportunity to enter the political and social arena. The economist Otto Nathan, the executor of Einstein's legacy, argues that the political content of the anthology is more important to the reader than the scientific part. Born in a humble background and proud of the prince, Einstein's reflection on the future and destiny of mankind and culture was as diligent as his exploration of the physical origins, and he put into the political movement with great enthusiasm and energy, and this volume reflects such a beginning. He had a keen political insight and courage rarely found among scientists, confronted the arrogant and demagogic forces of the moment, and always stood with the victorious side of progress, equality, and freedom. And those hopes and efforts that he ran for but were finally dashed (such as the U.S.-Soviet reconciliation, the world government, the Arab-Israeli reconciliation, etc.) were similar to his scientific career, and later proved to be a difficult subject that required many generations to work hard to find answers. Einstein's political activities represent a part of the pole and mainstream values of Western politics that have finally developed from a trickle of water to develop a view of the lake and the sea, that is, the civilian values of freedom and progress, but also have the basis of cultural and rationalist elitism.

Einstein's political writings are a key to understanding Western "modernity." More than half a century after his death, this is still the case. Due to the contradiction between cultural pluralism and social identity and administrative cost efficiency, which has led to the rampant populism and extremism, which has become another huge challenge facing Western society after nuclear war and environment, the academic boom set off by Said's "Orientalism" is a manifestation. In the early days of Einstein's political development, such a diary of a private nature unabashedly recorded the observations and cognitions of a representative of European culture on the Orient, and it is conceivable that it became the object of study of cultural and social scholars. As an example, readers can read Zeff Rosenkrantz's Diary of Einstein's Travels to the Far East, Palestine and Spain from 1922 to 1923.

Editor-in-Charge: Zang Jixian

Proofreader: Zhang Liangliang