The Edge of Crisis: An article to understand the storm of U.S. debt defaults

"Sometimes nothing happens for decades, sometimes decades of big things happen in weeks."

- Lenin

Over the past few weeks, the turmoil in the U.S. banking sector has faded from view. However, a brewing thunder has once again sounded the crisis alarm – a storm of US debt defaults has swept the front pages of financial news.

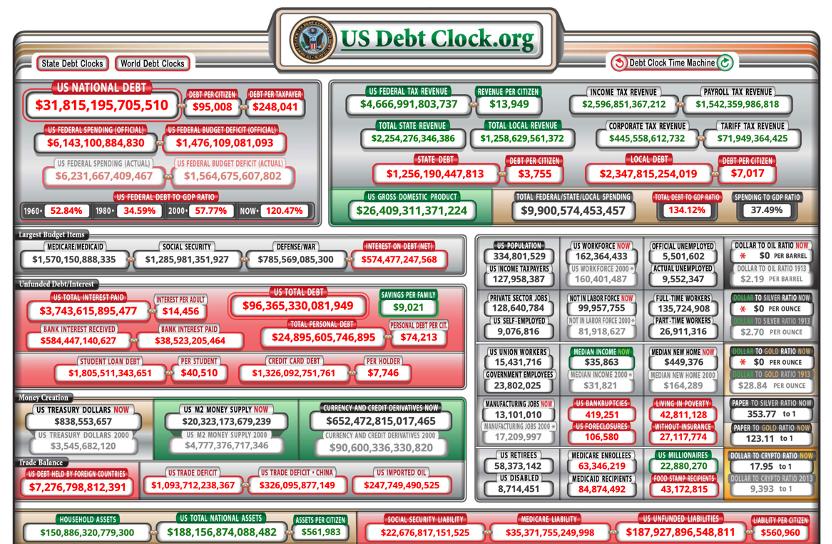

As the national debt grows and deadlines approach, the U.S. debt clock is turning into a ticking time bomb.

New York real estate mogul Seymour Durst, who built the U.S. Treasury Bell, once said, "If it's annoying people, it's working." ”

On the issue of U.S. debt, the U.S. government has recently engaged in what may be the most costly cowardly game in history. The outcome is the fate of the U.S. financial system and economy, and it poses a threat to the global economy.

A game of chicken is a confrontation between two or more people or groups where each tries to bring the other to its knees, but the result of both sides being intransigent is the worst outcome for both sides.

If Democrats and Republicans fail to agree on allowing the United States to borrow more — or, in their words, raise the debt ceiling — the world's largest economy will not be able to service its $31.4 trillion debt.

The U.S. Treasury debt has long been the subject of major political controversy. Although the U.S. government has defaulted zero times in modern history, it has often reached an impasse over government-imposed borrowing limits that have broken down over negotiations.

The bipartisan farce over the debt ceiling in the United States intensifies as "X Day" (the date when the US government is unable to meet its legal obligations to pay its bills) approaches, and if an agreement is not reached before "X Day", the US may default on its debt for the first time in history, with disastrous consequences for the US economy and ripple through global financial markets.

Fortunately, the latest news is that the US government has reached a preliminary agreement on raising borrowing limits and saving the country from catastrophic defaults days before it may start running out of money.

However, the matter is far from over. Even if the U.S. avoids a last-minute default, the economy will suffer.

| The Eye of the Storm: The U.S. Treasuries and the debt ceiling

Debt has been part of U.S. history since the beginning, and the United States has had public debt for longer than it has been a nation.

U.S. Treasuries are the sum of the deficit and the total amount owed to creditors in the past year, divided into internal government debt and public debt. More than three-quarters of that is public debt, held by individuals, businesses and foreign governments that buy treasury bills, bills and bonds. The remainder is intra-government debt, also known as intra-government holding, which is money borrowed by the government from trust funds to pay for programs such as social security and health insurance.

The US debt level ranks first in the world, and the ratio of national debt to GDP reached a new high since World War II with 134.84% in the second quarter of 2020. (The ratio is seen by economists as an indicator of a country's fiscal sustainability.) )

Apart from Denmark, the United States is the only country that has passed a law setting a specific currency cap on its national debt. (Australia instituted such restrictions during the 2007-09 global financial crisis, but repealed them a few years later.) )

Before setting a debt ceiling, the U.S. Congress was free to control the nation's finances. During World War I, Congress passed the Second Liberal Bond Act of 1917, which gave the Treasury more flexibility to issue bonds and manage its finances, making it easy to issue bonds without congressional approval every time it needed to raise money—a rather cumbersome process. Congress will set an overall limit on borrowing, the debt ceiling.

Simply put, the debt ceiling is the maximum amount that the United States can borrow cumulatively by issuing bonds, the amount that the Treasury can borrow to pay bills and other expenses when due.

The advantages and disadvantages of the debt ceiling are obvious.

Advantages include control over state finances, funding government operations, and improving the efficiency of government funding obligations such as social security and health insurance benefits.

The most obvious drawback is that funds can be easily raised, which encourages irresponsible fiscal behavior. Once something goes wrong, the U.S. credit rating lowers and increases its cost of debt.

In addition, the effectiveness of the debt ceiling has also been questioned, but Congress shows no signs of turning to other options.

| The debt ceiling was broken, and the default alarm sounded

The debt ceiling is a nominal number that does not actually make any basic economic sense. It was created to make the government run more smoothly, which means it needs a political solution.

Every time Congress passes a budget that exceeds the debt ceiling, the debt ceiling is automatically raised. However, the Senate or the president could still refuse to raise the debt ceiling.

Congress already knew how much debt would increase when it approved the annual budget deficit. When Congress refuses to raise the debt limit, it means it wants to spend money but doesn't want to pay the bill, the equivalent of credit card companies allowing individuals to spend more than their limits but refusing to pay stores.

Every once in a while, Congress votes to raise or suspend the cap in order to borrow more money to fund the government. There are often conflicts between the White House and Congress at this time, with the debt ceiling being used as a bargaining chip to advance the budget agenda. In the past, some conflicts over the debt ceiling have even led to government shutdowns.

On the evening of June 1, the U.S. Senate passed a bill on the federal government's debt ceiling and budget, the 103rd time the U.S. Congress has adjusted the debt ceiling since the end of World War II. At present, the size of the US federal debt is about $31.46 trillion, accounting for more than 120% of its GDP, which is equivalent to 94,000 US dollars in debt per American.

When the amount of outstanding debt reaches the ceiling, if Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling, the Treasury Department will take "extraordinary measures" to temporarily keep government borrowing below the limit. This is mainly achieved by stopping investments in certain government funds. That would buy some space for the debt ceiling and allow the Treasury to borrow more.

However, this is only a delaying measure to delay time in exchange for space.

If debt continues to grow and revenues are consistently unable to fill the outstanding debt gap, the U.S. government will eventually exhaust its "extraordinary measures" and run out of funds. Once the debt ceiling is reached, the government cannot borrow to pay bills and fund projects.

In other words, if the US fails to reach an agreement to raise the debt ceiling before it runs out of money, it will either face a sovereign default or a deep cut in state spending.

Either outcome will hit the U.S. and global markets hard. Default undermines confidence in the U.S. financial system; Sharp budget cuts could trigger a deep recession in the United States.

Bernard Yaros, an economist at international rating agency Moody's, said: "This will deal a heavy blow to the economy and it will be an artificial crisis. ”

| On the cusp of default: Rich but Broke

Financial markets have begun to experience turbulence, but these ripples pale in comparison to the tsunami when a default looms.

A default can occur in two stages.

First, payments to Social Security recipients and federal employees can be delayed.

Next, the federal government will not be able to repay debt or pay interest to bondholders.

A former White House chief of staff described the debt problem facing the United States as "the most predictable economic crisis in history." ”

There is no precedent for default in U.S. history, but hitting the debt ceiling, even if that were a possibility, would pose a serious threat to the economy.

According to the calculations of research institutions and economists, whether the United States has the possibility of defaulting, close to defaulting, or actually defaulting, its scope of impact will be multifaceted, and the degree of damage will be multi-layered.

Financial markets: The 2011 debt crisis showed that approaching the debt ceiling can also have a negative impact on financial markets. At the time, the U.S. reached an agreement to raise the debt ceiling just hours before the government ran out of money, which led credit rating agency S&P to downgrade U.S. debt for the first time. Stocks plunged, with the Dow down 17% in the weeks before and after the crisis. So, what could happen in financial markets includes: runs, sell-off and trading frenzy, excessive stock market volatility, increased credit costs, rising interest rates on credit default swaps, the threat of credit rating downgrades—all of which are risks with lasting consequences years to come.

Real economy: Any type of default puts enormous pressure on the real economy. Social Security payments will be delayed. This will cause hardship for many, causing consumers to panic, stop spending, lose a lot of jobs, further slow the economy, and possibly even trigger a severe recession.

Degree of impact: The damage caused by a default will depend on how long the crisis lasts.

According to Moody's forecasts, a brief default would be "enough to disrupt an already fragile U.S. economy." The default lasts about a week and will result in the loss of 1 million jobs, including in the financial sector, which has been hit hard by the stock market decline. The unemployment rate will jump to around 5 percent and the economy will contract by nearly 0.5 percent.

The impasse will last six weeks and more than 7 million jobs will be lost, unemployment will soar to more than 8 percent and the economy will slide by more than 4 percent.

These effects are still being felt a decade later.

The far-reaching impact is difficult to fully predict, but some once "unimaginable" scenarios of catastrophe are becoming predictable: from shockwaves through financial markets to bankruptcies, recessions, and potentially irreversible damage to America's long-standing position at the center of the global economy.

| How to solve the US debt crisis

Solving the debt problem is a difficult task that can take decades. Basically, every time the U.S. government touches this self-imposed debt ceiling danger, it simply modifies it.

Politicians usually argue about it, but eventually reach a consensus to postpone the problem until later.

This is a simple and difficult decision, and it is clear that suspending or raising the debt ceiling will not fundamentally solve the problem, the key is whether the US government pays its debt and meets its obligations.

In fact, since 1978, the US has adjusted its debt ceiling at least every 9 months on average, soaring from $1 billion when it was first introduced in 1917 to $31.4 trillion today.

The two most obvious ways to reduce debt are open source and throttling, which for the United States means raising taxes and cutting spending, but neither is an easy choice.

Both higher taxes and spending cuts are a drag on economic growth. In such cases, formulating relevant plans and measures is tantamount to doing more harm than less. This is one of the reasons why political parties in the United States often have a contentious stalemate on the issue of debt.

Given that resolving the debt problem will ultimately be a complex, tricky, and lengthy process, several "simple" (fantastic) solutions have been proposed.

It has been suggested that the government might try issuing "premium bonds" to play around.

In this way, the Treasury can issue "premium" bonds to raise money at higher than market rates, thereby raising money without technically violating the statutory debt limit.

The idea was recently floated by economist Paul Krugman, which came up during the 2013 debt ceiling crisis.

This bond consists of two parts – principal and interest. Obviously, only the principal is considered part of the debt ceiling. Interest does not count.

Now, suppose there is a $100 debt ceiling. The government can issue a $100 bond and promise to repay it within a year, then pay 5 percent interest. But once it does, it has hit the debt ceiling and the government can't borrow more.

If you want to borrow $200 up to the $100 limit. What to do?

At this point, the U.S. government can issue a "premium bond" and say to the public: "Come on, we'll sell you a $100 bond, but we'll give you 110% interest!" By the end of the year, we will return you $210. ”

So actually, the face value of the bond is $100 and the interest is $110. This is the basic composition of a "premium" bond.

However, the government will only sell you for $200. So technically, they didn't break the ceiling because the debt ceiling only counts the face value of the bond, not the amount that investors pay to buy the bond. That would allow the government to pay off existing debt with an additional $100.

In addition, the Government can continue to do so each time it approaches the limit. The debt ceiling becomes irrelevant.

This method sounds too outrageous and unlikely to happen. But who knows? In 2020, oil prices fell to negative territory...

Another gimmick is the $1 trillion magic coin!

The U.S. government is bound by existing laws when issuing currency, including strict regulations on the denomination of banknotes and gold, silver, copper coins and other coins.

There is also a loophole here, the denomination of platinum coins is not limited.

Under 31 U.S.C. § 5112, the U.S. Treasury Department permits the minting of platinum coins of any denomination, at the sole "discretion" of the Secretary of the Treasury.

This means that the U.S. Treasury can mint a platinum coin worth $1 trillion, deposit it with the Federal Reserve, and use it as collateral to borrow money to pay off the national debt.

The debt ceiling problem is easily solved!

Moreover, there is simply no need to have $1 trillion worth of platinum to mint coins. It could just be a platinum commemorative coin with a denomination of $1 trillion.

Actually, this is not a new idea. It was proposed in the 90s, and during the 2011-2013 debt crisis, the idea of minting platinum coins was hotly debated online, and even launched an online campaign of #MintTheCoin.

Theoretically, this could solve the problem, but only temporarily. Because sooner or later the ceiling will be reached again.

The only problem is that this puts the United States in an awkward position. Because it is akin to the government printing new money out of thin air, which should be the responsibility of the Federal Reserve (the US central bank). If investors see that the government is interfering in the process, they may be wary of investing in the country. That will only make the bad situation worse.

So, to sum up, there are 3 simplest, direct and crude ways to solve the US debt crisis:

1) raise the debt ceiling;

2) issuance of premium bonds;

3) Mint $1 trillion of magic coins.

(Zhang Xiaoquan is Associate Dean of Business School, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Professor of Decision Science and Business Economics)