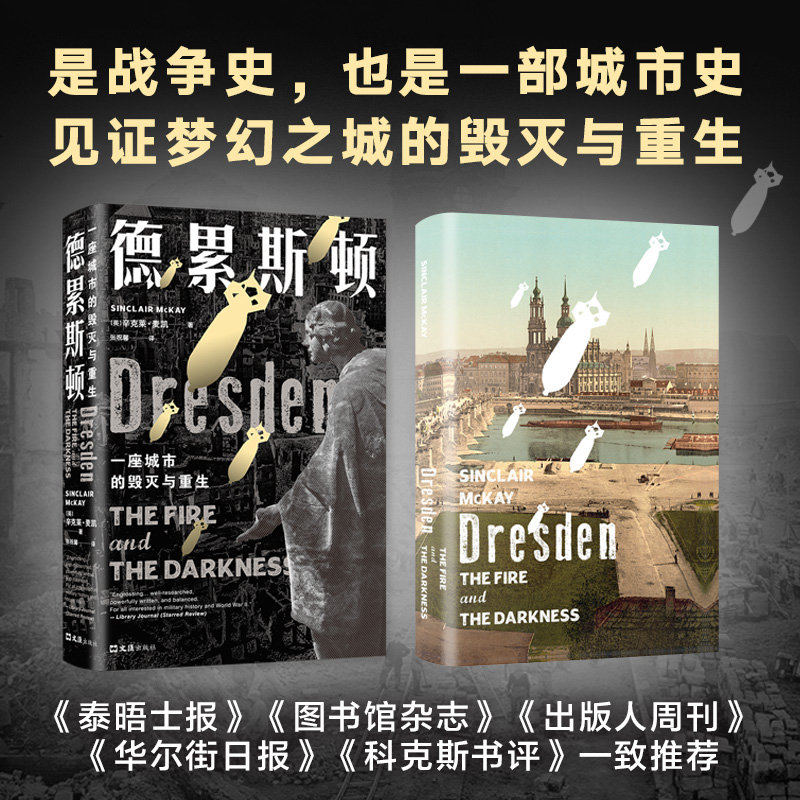

Dresden: The Destruction and Rebirth of a City

By Sinclair McKay

Translated by Zhang Zhuxin

Wenhui Publishing House

The book is both a history of the war and a history of the city: the author uses a large number of historical materials and archives, multiple characters and multiple perspectives to reconstruct the whole process of the Dresden bombing disaster, detail the moral controversies it caused, and witness the city's rebirth from the ashes from many perspectives.

>> background

On February 13, 1945, the end of the day fell from the sky, thousands of bombers flew by, and overnight, Dresden was reduced to ruins, and the "Florence on the Elbe", the center of European civilization, was blown out of the 20th century.

For Vonnegut, the event presents a brutal black humor: "Costly, well-planned, and in the end, meaningless." ”

One wonders, what is all this for?

Located in the east of Germany, in the heart of Europe, Dresden is run through the city by the winding Elbe River, bringing fashion all over Europe.

Here, the Renaissance temperament coexists with the Oriental style, the Gothic cathedral echoes the Baroque architecture, and philosophers call it "Florence on the Elbe".

Centuries later, literature and artists poured in, and Dresden was nurtured by its own unique style, nourished by multiculturalism. The Semper Theater, built in 1841, witnessed the golden age of German opera, where Wagner and Strauss presented a number of world-renowned plays and symphonic poems.

Sempa Opera House

In the 1950s, the poet Erich Castner recalled: "Dresden was full of art and history, past and present in harmony with each other. ”

By early 1945, World War II was nearing its end. No one would have imagined that this city full of artistic treasures would be the target of massive Allied bombardment. But the seeds of destruction have long been planted.

After the Nazis came to power, fascism swept through every corner of Dresden, all public buildings were draped in swastikas, and the streets were filled with SS and other minions. Even compared to the capital of the Third Reich, the level of fanaticism here is even better. Under the guidance of nazi "eugenics", 8219 sterilizations were performed in Dresden alone (6550 in Berlin in the same year). From before the war until 1945, the jewish population in the city plummeted from more than 6,000 to less than 200.

Art and education are not immune, either. In 1933, the first exhibition "Degenerate Art" was held in Dresden, and Hitler himself visited the works of art that the authorities denounced as pathological and degenerate.

Hitler visits the Fallen Art Exhibition

On all campuses, nazi organizations, from toddlers to teenagers, poisoned young minds.

Nazi children's organization German Girls' Union

Despite its rearward position, Dresden was not far from the war, and the factories that used to produce cameras, microscopes and typewriters were now all fully powered to serve the war, and a steady supply of military supplies was constantly on the front line.

In February 1945, the fire finally arrived. Overnight, thousands of bombers poured more than 4,000 tons of explosives down, turning what was once a dream city into purgatory. After the bombing, the ruins of Dresden resembled a huge grave, and the severity of the bombing became known to the British and American people as desperate survivors searched for traces of their loved ones among the rubble and masonry. The Nazi authorities spearheaded the public opinion offensive, with Goebbels exaggerating the casualties, claiming that more than 200,000 civilians had died in the bombing and cursing the Allied actions as "terrorist attacks."

The city before and after the bombing

The British media was also shocked by the results of the airstrikes, with the Daily Telegraph writing: "The disaster in Dresden is unprecedented ... A great city was erased from the face of Europe. ”

For their part, the British Air Force had already paid a terrible price for winning the war – only 1 in 3 aviation officers survived 30 bombing missions.

In order to end the war as soon as possible and destroy the Nazis' stubborn will to fight, strategic bombing of large cities was put on the agenda, and the British high command, including Churchill, approved the plan. However, when news of the destruction of Dresden reached the country, Churchill became suspicious of the bombing, writing in his memorandum: "Bombing German cities purely for the sake of terror, this strategy should be re-evaluated." He feared that the war had turned the British into "beasts", stripped of their minds by irrational violence.

Who is responsible for the destruction of Dresden? The discussion on this issue has endured and is even more enthusiastic than the attention paid to the Hiroshima nuclear explosion. During the Cold War, the ruins of Dresden became physical evidence of the terrorist atrocities of British and American imperialism under the "Iron Curtain" and stimulated anti-war movements on both sides of the Atlantic. To this day, german right-wing groups still try to exploit this incident in the hope of portraying Germans as victims of war crimes and brushing aside fascism.

In the face of numerous controversies, the truth of the Dresden bombing became obscure by accusations and resentments between different positions. In recent years, the local archives in Dresden have also been doing their best, collecting testimonies and accounts of witnesses. These sources vary. There are communications between high-level military leaders, and there are also personal experiences of front-line pilots. There are stories told by fashionable and young people, as well as diaries, letters and words left by adults who experienced the horrors of that catastrophe.

On February 13, 77 years ago, the city was destroyed by the madness of war. Now, 77 years later, it's time to lift the fog and witness the horrific destruction and the new life that comes after it.

>> wonderful trial reading

Freeman Dyson's Dresden moment

In the 1930s, a teenage boy boarded at winchester College, a historic British public school, who looked a little odd, mainly because he liked to hide complex math textbooks in a cricket pullover when he was forced to play cricket. The amused teachers would make the boy stand on the grass, stay where the ball is unlikely to roll, where he can stand comfortably, studying the most profound mathematical theorems while everyone around him is playing cricket.

It was a child prodigy who liked to stay "absolutely elsewhere"—a popular slang phrase of the time referring to the abstract soul, derived from the research terms of physicists who began to explore new areas of quantum. A few years later, the teenager was drafted into one of the most sensitive nerve centers of war: he possessed wild mathematical abilities and a mature sense of morality, and a deep understanding of the demands and weaknesses of war. Dresden was destined to be an important part of the boy's moral and philosophical growth.

In 1942 bomber command produced a map showing the city of Dresden and its public landmarks. At the top of the map there is a warning: No attacks on hospitals are allowed. The fact that the cartographer thought it was necessary to say such a thing would make one wonder who would target a hospital? The weary bomber crew died more than most people had ever seen, but there would still be unconscious cruelty, and even if they could try to comply with the ban, the fact that precision bombing missions were not supported by available technology.

The young mathematician witnessed all this and more: After the war broke out, Freeman Dyson was admitted to Cambridge University. He knew he wasn't going to be there for long, and he was sure to be pulled into some military operations department. In fact, he completed two years of reinforcement studies and learned more esoteric things like the Alpha/Beta theorem. Dyson was a skinny young man with big, piercing eyes, and at this stage he was reading Adolphus Huxley's 1937 book Of Ends and Means, a collection of philosophical treatises on nationalism, religion, war, and the cycle of aggression. "We insist that what we think of as good ends can justify what we recognize as bad means," Huxley wrote, "and we also ignore all the evidence and think that using these bad means can achieve the good results we want." He also pointed out: "In this matter, even the most intelligent people will deceive themselves." ”

In 1943, Freeman Dyson was drafted into the army. The authorities discovered his ingenuity and sent him to bomber headquarters. It is a red brick building located in the Chiltern Hills, just outside the town of Haywickcombe, Buckinghamshire. Dyson's quarters were close to town, and every morning he would ride his bike up the hill and travel five miles to bomber headquarters. Sometimes, on his way there, a limousine would pass him by, and in the back seat was Sir Arthur Harris.

Dyson was inducted into the Operational Research Division of Bomber Command. He joined the company in July 1943 during an eight-night raid in which the British Air Force successfully sparked a rare city fire over Hamburg, nearly a mile high. Dyson's division handles data analysis of all bombing missions, not the number of buildings that were blown up or the area that caused the blaze, but the death rate of crew members and how to reduce this terrible attrition — the fear that envelops every pilot and crew member who flies into the dark night sky.

Are there any factors that link bombers that were shot down or exploded in mid-air? Dyson recalled that at that time, the pilots and crew members were assured, the more experienced the flight practice, the safer they were, and the more sorties a bomber completed, the more skilled the crew were to avoid all the dangers that could be posed by the elite German defenses. Dyson analyzed statistics on non-returning planes, presenting him and his colleagues with the painful truth: Experience had no effect on survival probabilities. A pilot who has flown 29 sorties in the hinterland behind enemy lines could turn into a shiny orange fireball, as he did when he first started flying. When they flew to 30 sorties, the crews had only a 25 percent survival rate. In any air raid, an average of 5% of planes are missing, so the death toll inevitably rises after hundreds of airstrikes.

In Dyson's world, geometric theorems, which used to appear only on the blackboard, are now a matter of life and death. It took a long time for bomber command to fully understand all the dangers that the crew faced in the air. For some time in 1943 and 1944, they believed that planes that exploded without being hit by enemy fire collided with other planes in mid-air. Because the bombers were tightly formed and required all-out action, this meant that such contact was sometimes difficult to avoid.

But there was also a fatal danger factor that bomber command had not yet realized. Sometimes, when pilots return from missions, they mention the impression that their backs are chilling, and they feel that the German fighters are somehow invisible. Dyson speculated that the Germans might have implemented a technique that once existed only in theory: not stealth, but equipping their night fighters with airborne weapons that could be adjusted to angle upwards — the best angles were between 60 and 75 degrees, so that enemy aircraft flying below seemed invisible. He was right. The Germans refined the technology, calling the new night fighter "oblique music".

Dyson wasn't limited to stereotypical office work; he flew airplanes himself on several occasions, flying high in the summer and conducting aviation experiments. He had no complaints about his personal situation, and his support for the young crew members did not waver in the slightest. But in 1943 and 1944, when Arthur Harris chose more German cities as targets for high explosives and incendiary bombs, Dyson began to question the ethics of bombing operations.

He later admitted that when he was involved in the war, his ideological stance was very broad-based pacifism. However, he was also very clear that the Nazi regime must not be allowed to continue. The question then returns to the ends and means of Adous Huxley. Decades later, Dyson summed up his moral dilemma:

From the very beginning of the war, I retreated step by step from one moral position to another, and by the end of the war I had completely lost my moral position. At the beginning of the war, I... Morally oppose all violence. After a year of war, I backed down and I said, "Unfortunately, resisting Hitler in a nonviolent form is not going to work, but I am still morally opposed to bombing." A few years later, I said, "Unfortunately, bombing seemed necessary to win the war, so I was willing to go to bomber command, but I was still morally opposed to indiscriminate bombing of cities." After I arrived at bomber command, I said, "Unfortunately, it turns out that we are bombarding the city indiscriminately, but this is morally justified because it helps to win the war." A year later I said: "Unfortunately, our bombing didn't seem to really help us win the war, but at least my job was to save the lives of bomber crew members, which is morally justified." ”

But, he concluded, "in the last spring of the war, I could no longer find any excuses." ”

>> author profile

SINCLAIR McKAY is a British journalist, historical writer, literary critic and columnist for the Daily Telegraph and The Sunday Mail.

MacKay has long studied British wartime archives, represented as The Secret Life of Bletchley Garden.

Author: Sinclair? Mckay

Image source: Publisher

Edit: Jin Jiuchao