In 1791, the young writer Chateaubriand began his first trip to the Americas. In the shortly following book, On Ancient and Modern Revolutions, he wrote about the experience: going into America meant "a strange revolution churning within." This seems to indicate that the title of the book does not refer to the great political-social movement of the same period, but first and foremost to the American continent as a new world, a foothold far enough to contemplate the old world. Here lives "barbarians" who are neither modern nor predate the ancients, and which exist in a true state of nature, even further than Rousseau conceived.

To some extent, Pierre Claist's Chronicle of the Guayaqui Indians also inherits this writing tradition. Similar to what Levi Strauss did in The Melancholy Tropics, Klast's description of the Indians also undertakes a critical work of the traditions of the civilization in which they live: with the study of the other of civilization, we see a different possibility.

However, perhaps the first thing we need to ask is, what is "history"? The title "Chronicles of the Guayaqui Indians" can be divided into two parts: "indiens Guayaki" and "Chronique." This formulation implies a misplacedness: as far as the Guayaqui Indians themselves are concerned, they will not have a chronicle at all. In other words, this chronicle was not written by the Guayaqui Indians, nor did they need or even imagine such a thing. When we try to grasp the Indians through chronicles, we still stand in our own history. This dislocation is a form of destiny that once dominated the idea of "universal history." The Indians were silent, and all we could hear was our own echoes.

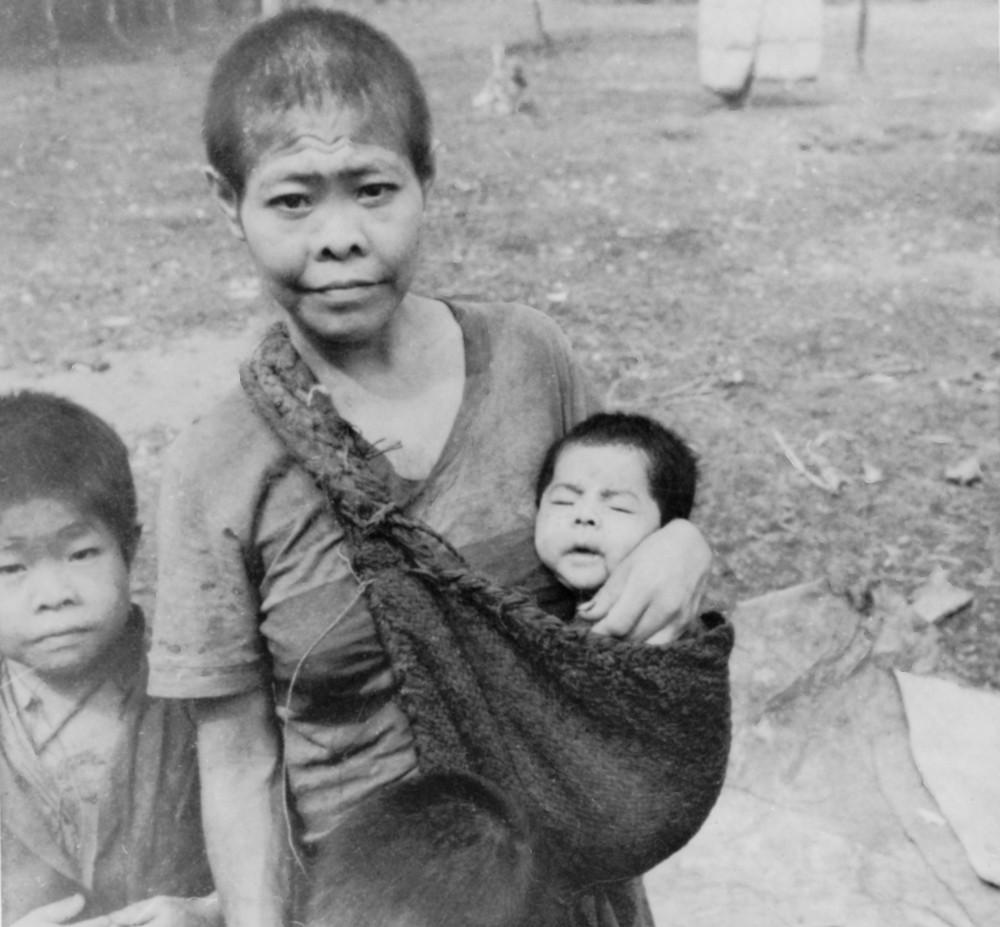

Pichuki and her baby

The presence of the Indians not only attests to the existence of an "anti-state society," but also confronts the white world in which Crest lives as a society that is still alive. The primitive society outside of history is unrecognizable and incomprehensible, but it has truly come to the present. Its life itself is a self-assertion that unquestionably emphasizes its gap with the modern civilization of whites and resists the historical consciousness of the latter. In the eyes of whites, the Indians were always silent; Klaster's work sought to show that the Indians were not merely objects of interpretation, but that they also had their own voices. He wanted the silent Indians to speak for themselves, so he deliberately retained the Indians' own vocabulary in his writing without translating them. Through these efforts, Crest is trying to present not a redefinition of indians by whites, but an understanding of indians about themselves, whites, and the world as a whole.

In other words, Crest wanted to go to the other side of the chasm. This is also the dream of almost all anthropologists, but it is not easy. Klast was well aware of this. Therefore, he did not establish a biography of the Indians according to the chronicle style. We can hardly see the Year AD, after all, there was no Jesus incarnation among the Indians. The author also rarely uses the term "age" to introduce his Indian friends. He had witnessed events, and through his observations, he knew what had happened earlier, but he had not tried to attribute them to a unified, one-way timeline. It is not so much a chronicle as a memory: both of Crest himself and of the Indian tribe in which he lived, fragmented, alive, concrete, unregulated, and at the same time perishable, error-prone, always accompanied by forgetting and fantasy.

Klast is also clear that the success of this work does not depend on himself. He quotes the proverb of Alfred de Metro: "If we are fortunate enough to study a primitive tribe, it must have begun to decay and disintegrate itself." "If we succeed in crossing the chasm, it only means that what we are crossing is not a real chasm. In fact, the whole book is shrouded in the tragic atmosphere of this sentence, which further implies that the attempt to let the Indians speak for themselves already foreshadows that they will soon lose their voices completely. Crest was able to approach and enter the Guayaqui Indians because the Acetic tribe had been sheltered by a Beeru (white) many years earlier. Thus, long before Crest, the Guayaqui Indians had entered white territory.

Young Chachuki's coming-of-age ceremony

In the beginning, it was just a relationship similar to an alliance. For the Indians, the incident did not cause much panic. It is true that whites always played the role of invaders, but after years of dealing, the Indians had learned how to place whites in their own spiritual order—

This has been the case ever since the dawn of time, when everything was distributed between the natives and the whites, between the poor and the rich. The Guarani thought the same thing: fate gave the lion's share of the lion's share to the whites, but the Indians had to keep the share that fell into their hands, and they could not give it to the whites.

All people, things, and events can be placed in this order and thus reasonably explained. It is a cyclical cosmic order, with life, old age, illness, death, hunting, sacrifice, festivals, alliances, and so on, all attributed to the constant movement of nature and destiny. Tribes are isolated as civilized places from the dangerous natural world around them, but they share the same rhythm and flow with each other. Therefore, there is no absolute distinction in the indian world: the souls of the dead are difficult to disperse, hostile tribes can be reconciled and become friends, and even fierce animals have secret ties with humans. In the legends of the Guayaqui Indians, the jaguar is not only a ferocious animal, it also symbolizes darkness and danger, it threatens not only the tribe, but also the entire cosmic order. The confrontation with the jaguar, like the existence of the jaguar itself, was eternal, and the Indians never imagined a complete victory in this confrontation once and for all. This is impossible, because the jaguar also means the destination of the human Ove (soul). After a person dies, its soul becomes an animal, sometimes a raccoon, sometimes a jaguar, sometimes a poisonous snake, and so on.

kybuchu (meaning "child")

Apparently, the appearance of whites impacted the indians' original cosmic order, but they soon incorporated it into the new order, although this inevitably brought confusion and contradiction. However, the use of integration theory to demand this order may only be the wishful thinking of modern people. For the Indians, this order retained great flexibility, which meant that the ambiguity of the world itself was presented clearly enough. Whites do not have a fixed position in the order, and in this passage whites occupy two positions at the same time: on the one hand, they are the same as the natives, and their distinction from the natives is no different from that between the poor and the rich; on the other hand, the whites' share is obtained from the lions. Comparing white people and animals, thereby excluding them from civilization as understood by the Indians, resisted, humiliated, and respected these white people. White man invades, a new danger has come, but it will not shake the cosmic order on which we depend; everything has been arranged, and the white man has become the new jaguar in this land, and we curse it, but also accept it.

However, the influence of the whites eventually exceeded the expectations of the Indians, who were far more terrifying than the jaguars. Faced with the traditional rituals of the tribe, the girl escaped because of fear. Klaster was keenly aware that behind her genuine fear was the disintegration of tradition, desperate to invade the tribe, and it was all because they had left the forest and come to the white man's territory. Under the onslaught of the whites, the once-convincing cosmic order had begun to lose its appeal, and the promise of the reincarnation of all things had failed, and they were horrified to see that behind these rituals, apart from empty pain, there was only a dark and bottomless death.

In the last chapter of the book, Klast talks about the Indian cannibalism, and in fact it took him a long time to learn about this most controversial and incomprehensible act of modern man. Among the Indians, cannibalism was not an act of eating for the sake of protein, but the attitude of the living towards the dead: if the dead were not eaten, their souls would linger among the living and hinder their lives. For the Indians, this "ghost" is enough to be anxious enough. But what exacerbates this anxiety is the white man's ban on cannibalism, which they must abide by, or the white man will not allow them to continue to live on the land.

This in itself caused more anxiety until the spiritual world of the entire ethnic group collapsed completely. In the author's recollection, the cannibalism event marked the decay of the Guayaqui Indians. The spiritual order they possessed was destroyed, and the world became foreign to them again. Until then, they were able to explain everything that fate had given them, which was at the heart of meaning for the entire universe. And now, the Indians have come to the real Jedi, with incomprehensible dangers ahead and a gradually lapsed cosmic order behind them. They can't understand white people, and they can't understand themselves at the same time. There's nothing more worrying than that.

The title "Chronicles of the Guayaqui Indians" recounts not history, but Crest's memories, or rather a drama formed through memories. The play begins with the birth of a baby and ends with a cannibalistic ritual. The drama shows the defeat of the Guayaqui Indians' self-assertion: they once had a grasp of the order of the whole world, but with the invasion of the whites, they were thrown into history, and everything became a dead leaf, and the last sound left was an unrecognizable elegy. The Indians fell into complete silence.

Lad Kagapuguki

Klaster's contribution is not only to give us a glimpse into the spiritual order of the Guayaqui Indians, but more importantly, he shows how this spiritual order gradually disintegrates in the midst of internal and external troubles. In fact, it is not until the epilogue of the book that he talks about "history", where he also tells the epilogue of the Indians:

What about those who survived? Like unclaimed lost objects, they left the prehistoric era in which they lived in the twilight and were thrown into a piece of history that had nothing to do with them and would only destroy them. But the truth is, none of this is a big deal: just another page of boring census reports—with increasingly precise dates, place names, and data—once again documenting the disappearance of the last Indian tribes.

The Indians were thrown into history, only in the form of destruction, because that history belongs to us but not to them. Only at the end, a "chronicle of the Guayaqui Indians," recorded in the form of "precise dates, place names, and data," could be written, premised on the demise of the Indians themselves. In this sense, Crest's writing is against this cruel, paradoxical title. Yet the Indians' "chronicle moment" came unstoppably.

Guayaqui Introduction

The Guayaqui, a group of Indians who live in the dense forests of Paraguay. They make a living hunting and gathering, and have their own language, customs and social system. Since the 16th century, Western colonists, together with local residents, have continuously occupied and devoured the territories in which they live, hiding, resisting, exile, and being "resettled"... By the end of the 1960s, the population of the tribe was less than thirty.

Chronicles of the Guayaqui Indians Author: Pierre Klast Publisher: Shanghai People's Publishing House Producer: Century Wenjing Translator: Lu Guiye

In 1963, the author of the book, the young French anthropologist Pierre Claist, entered the tribe after the Guayaqui were settled in settlements, living with them, making nuanced observations of their fertility, death, diet, courtship, tribal management, sexual identity, division of labor, etc., completing a kind of ethnography full of humanity.

Author: [French] Pierre Crest

The book has been evaluated as an objective ethnography, a swan song dedicated to the Guayaki people. The author, Pierre Clastres, born in 1934, died in a car accident in 1977.

(Editor-in-charge: Sun Xiaoning)