Although Jacques Colin de Plancy's Dictionary of Hell, a synopsis of the immortality of demons, was a great success when it was first published in 1818, it was the beautifully illustrated final edition in 1863 that made the book a milestone in the study and depiction of demons. Ed Simon explores the work and how at its core is an unlikely but pertinent synthesis of Enlightenment and mysticism.

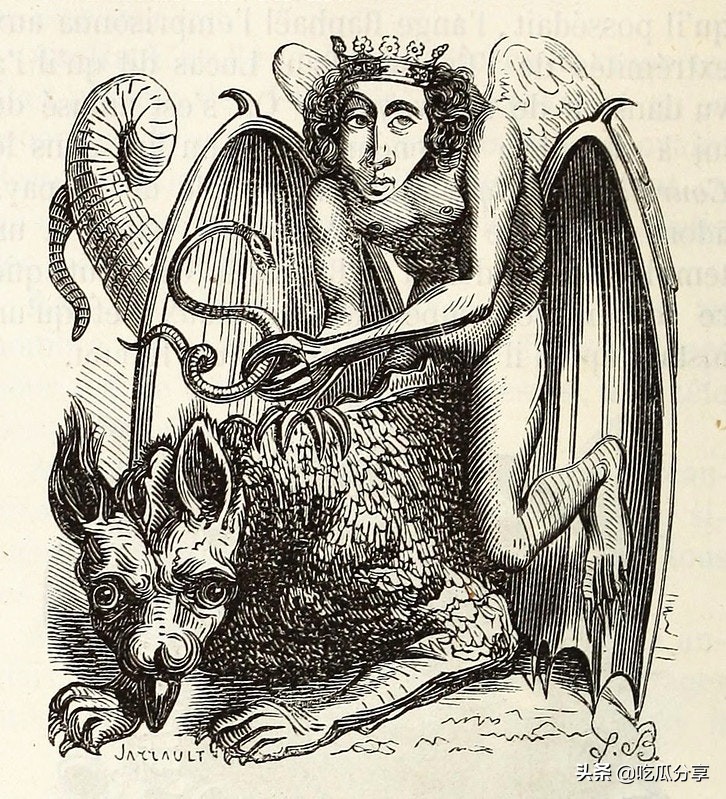

Between the entrance of a 17th-century Anglican theologian Ashton and a Mediterranean goddess, Astatt, is the demon Astaros. As depicted in the Dictionary by the French artist Louis LeBreton for his compatriot Jacques Abin-Simon Colin de Plancy, Jastaros was a skinny man with reptile claws poking at his long hands and feet, limping on the back of a wolverine with a pair of huge bat wings and a snake-like tail. Collin de Plancy described his face as a "very ugly angel," while Le Breton portrayed it as thin, almost as thin as a horse, with a contemptuous and indifferent look in his eyes, slightly sneering. Aside from Jastaros's claws and demonic mounts, his elaborately designed expression of wisdom is like the intellectuals of his youth who dined with Colin de Plancy's Enlightenment Parisian philosophy.

This is not entirely inappropriate, as dominican inquisitor Sebastian Michellis classifies the demons he encountered during the exorcism of the infamous Lauden Abbey in the 17th century as Astaros and associates it with the neo-rationalist philosophy that had just been born in France. Jastaros of Michelis was a kind of hellish Descartes who led Luton's nuns and priests astray with the vicious promise of Epicureanism and the invitation to "do what you want." Perhaps for Colin de Plancy, who was born in the revolutionary upheavals of nearly two centuries later, this thin, aristocratic reptile demon still represents some of the dangers of new knowledge, for Jastaros "is happy to answer the questions he is asked about the most secret things, and... It's easy for him to talk about creation. ”

Jastaros is the eccentric symbol of Colin de Plancy's Dictionary, because demons represent a chaos of cultural forces: rationalism and superstition, systematization and mysticism, enlightenment and romantic movements. When the Dictionary was first published in 1818, Colin de Plancy, a devoted student of Neo-Rationalism, set out to catalog what he called "deviations, bacteria, or causes of errors." However, as he struggled to write the later editions, the secular folklorist found himself increasingly attracted to the temptations of demonology, a passion that eventually led to his passionate Catholicism in the 1830s. By the final edition of the dictionary in 1863, the publisher could assure the reader that the previously emphasized "errors" had now been eliminated and that the table of contents was now fully consistent with Catholic theology. The preamble authoritatively declares that Colin de Plancy has "reconfigured his work, recognizing superstitions, foolish beliefs, mystical sects and practices... Only those who turn their backs on their faith will come. ”

Colin de Plancy wrote nearly 600 pages of 65 different demons, including the favorites of Dante, Milton, and others such as Asmodius, Azazer, Belbel, Belberg, Belfigor, Belzebus, Marmon, and Morlock. The most interesting edition of the book is the last edition in 1863, exemplified by le Breton's eerie precision, whose brilliant Dole prints make the work more stable than the previous edition.

The thought of the grandeur of some of these illustrations is both inspiring and frightening. Among these little demons, for example, were "Adra Miller, the Great Prime Minister of the Underworld, the Chief steward of the Wardrobe of Demon Monarchs, the Chairman of the Devil's High Council", who "appeared in the form of a mule, sometimes even in the form of a peacock". Le Breton, in his illustrations, depicts him as a donkey-headed version of the Yazidi "peacock angel," full of conceited glory. Andusias, who has the "unicorn shape", has a voice like "tree bowing" and "commanding twenty-nine legions".

A few pages later, Amun appeared, a terrible hell beast with black eyes and a "great and mighty marquis of the Hell Empire." Its head resembles an owl, and its mouth exposes very sharp canine teeth. As if LeBreton's depiction of the beast wasn't scary enough, Colin de Plancy reminds us that this nightmarish creature "knows the past and the future."

Then there's Effieartis — a little goblin with a pug face, bird wings, wild eyes, perched on a man's chest like Fuseli's nightmare — whom Colin de Planci described in one sentence, explaining that he came from "the Greek name of the nightmare... It is a spell that inhibits sleep. ”

And then there's Eulenom, who "has long teeth, a terrible body full of wounds, and is dressed in fox skin." Le Breton portrays Eurynom as an animal with bent knees and jagged teeth, grimacing at an invisible victim and "exposing his big teeth like a hungry wolf."

And my favorite, Belfinger, he curled up there, brow furrowed, taut on the toilet, tucked between his tails, trying to.

Of course, Colin de Plancy's concern in the Dictionary about hell is not just the defecation of little devils. He also aims to provide guidance on historical and practical utility, more exalted among Satan's servants. Then there's Asmodes, who the Talmud claims to be the descendant of a banshee who slept with King David, but Colin de Planci believes he is "the ancient serpent who seduced Eve". Driven by desire, Asmodius is portrayed as a terrifying three-headed monster, and although he does not have one above King Solomon's command (believed by mystical tradition to have a special ability to control demons), he "shackles him and forces him to help build the temple of Jerusalem".

Or think of the "heavy and stupid demon" behemoth. Colin de Plancy recalls his appearance in the Book of Job, writing that some "commentators pretend it was a whale, others think it's an elephant." Le Breton chose to portray the "behemoth" as a bipedal version of the latter, clinging to his hairy, plump belly like some kind of vicious Gunnish.

There was also Bell, "the first king of hell", who had "three heads, one in the shape of a toad, another in the shape of a man, and the third in the shape of a cat", and Le Breton added some furry spider-like legs to his head.

The connection between the ideals of the Enlightenment and the old world of magic and superstition, in many ways, was made possible by Colin de Plancy himself. He was born in 1793, just four years before the culmination (or most condemnable) event of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution. Perhaps in response to that incident, he added a nobleman's "de Plancie" to the name of his original commoner. In fact, it was not just a civilian name, but a name with an active connection to the Republican Party, for Colin de Plancy's maternal uncle was none other than George Danton, the radical chairman of the Public Safety Council, who, like many of his Jacobins, finally found himself on a morning in Jerman's month when he found his severed head looking up at the guillotine blade.

Like his uncle, Colin de Plancy was initially a champion of liberty, equality, and fraternity, an avid reader of Voltaire, an avid rationalist and skeptic; Like his uncle, he will eventually see himself reconciled with the church he once rejected, despite taking a detour in the dark corners of demonology. In his dictionary, filled with many demonic fantasies, Colin de Plancy is a mixture of different parts.

He combined the linear logic of Voltaire and Diderot with the long visions of symbolism and decadent poets a generation later. Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Verlaine, drunk on the streets of Paris in the rain, clutching their lilies colin de Plancy, not only convinced himself that demons were real, but he also developed a desire to control them through language, like his Predecessors of the Enlightenment, eager to classify and define words and ideas in dictionaries and encyclopedias. The demonologist is a man who hovers between logic and faith, between sharon and the Hellfire Club, who hears the screams of terrible monsters while writing with the sober pen of a naturalist.

Like its creators, the dictionary spans interest across two eras. The book is reminiscent of John Wayyer's 16th-century Fictional Monarchy or Solomon's Little Keys in the 17th century, as well as to the systematic intellectual compendium of the Enlightenment, such as Dennis Diderot's Encyclopédie. The plan of the book itself is ambiguous, for what could be more modern than a dictionary, but what could be older than the knowledge it collects?

Although there are ancient and medieval precedents in several different cultures (you can think of Aristophanes of Byzantium, who compiled a dictionary called Lexeis two centuries before the birth of Christ), dictionaries, and especially encyclopedias, are products of the 18th and 19th centuries. For Dr Johnson and his Dictionary of the English Language, or James Murray, who compiled human wills in the oxford university's manuscript room, the Oxford English Dictionary, positivist knowledge can be found in the process of collection and measurement. This dictionary is serious, rational, and practical. Etymology is like anatomy, another innovation of the Enlightenment, and dictionaries are like anatomical theaters. For Johnson, the dictionary was a reaction to "linguistic richness and disorder, energetic and irregular" that it was used to tame the vocabulary because its linguistic approach was a "reduction to method."

What about Colin de Plancy's Hell's version? Is this a dictionary written by name only, or does this kinship touch on a deeper vein? In his book The History of the Book of Magic, historian Owen Davis writes how the Book of Magic was labeled "a thirst for knowledge and an enduring urge to limit and control it," a description that certainly applies to the projects of Johnson and Murray. "Magic books exist," he continued, "because people want to create a physical record of magical knowledge that reflects people's attention to the uncontrollable and perishable ... Divine Message. "While the great experiments of the Enlightenment were thought to shine the light of reason into the shadows of superstition, the desire to gather all possible information was common to magic books and dictionaries. This desire for wholeness and all-encompassing is not just superficially similar, for magic books and dictionaries share a common belief in their obsession with words and language—that mere verbal statements have the ability to rewrite reality itself. Both types of books are proponents of Platonic philosophy, arguing that a word magic can produce transformations in real life. For rationalist lexicographers, this meant that a mastery of rhetoric and syntax could influence our lives through the ability to explain and persuade; For wizards, this means that the magic of language can change. In both cases, words have power and, if properly organized, can change the world for better or worse.

At the heart of this shared mission is that both magic and reason have an inspiring belief in the intrinsic interpretability of reality: that there is an established order in the world, and that order can be understood and controlled by the human mind. Whether this order is supernatural or natural, it is all accidental; The structure of the system is the most important. Colin de Plancy's dictionary may be a magic book, or his magic book may be a dictionary, but fundamentally, the difference between them is not as obvious as imagined.

Elan Stavance writes, "Dictionaries are like mirrors: they reflect the people who produce and consume them." If this is true, then the hell in the Dictionary is a reflection not only of Colin de Plancy (a man who lives in the shadows but longs to illuminate), but also of our modern world. Dictionaries list words like demons, focusing on the correct order and grammar (lest our spells not work), so dictionaries can be seen as modern, secular magic books. The "hell" in the Dictionary is not an ancient relic, and it reminds us that the sharp distinction between ancient and modern is ultimately meaningless. Our world has always been, and will always be, a world of demons. But, apologizing to C.S. Lewis, the magic book proves not the existence of demons, but that they can be tamed. If there's a little comfort, it's that as long as we can name our demons, we have the possibility to control them, whether they're supernatural or rationalistic—in either case, we need a dictionary.