Clinical problems

Does schistosomiasis cause blood in the stool?

Case introduction

Patient age: 28 years

Patient sex: Male

Brief history:

Half a month for blood in the stool.

I have lived in Uganda for a few years before and often swim in the Nile.

After returning home, he had repeated diarrhea.

Three months after returning home, he underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis.

After returning home, 8 months later, intermittent blood in the stool appeared. During this time, he did not vomit, have a fever or lose weight. After evaluation, vital signs are normal, and abdominal examination shows a soft and painless abdomen.

Rectal examination is normal.

Auxiliary tests:

A complete blood count shows a normal hemoglobin level and an absolute eosinophil count of 304 cells/microlitre.

Stool microscopy, HIV fourth-generation testing, hepatitis B serology, gonorrhea, and chlamydia rectal swabs are all negative.

Colonoscopy shows granular mucous membranes in the rectum. Internal hemorrhoids are present, but there are no masses, no vascular malformations or other abnormalities.

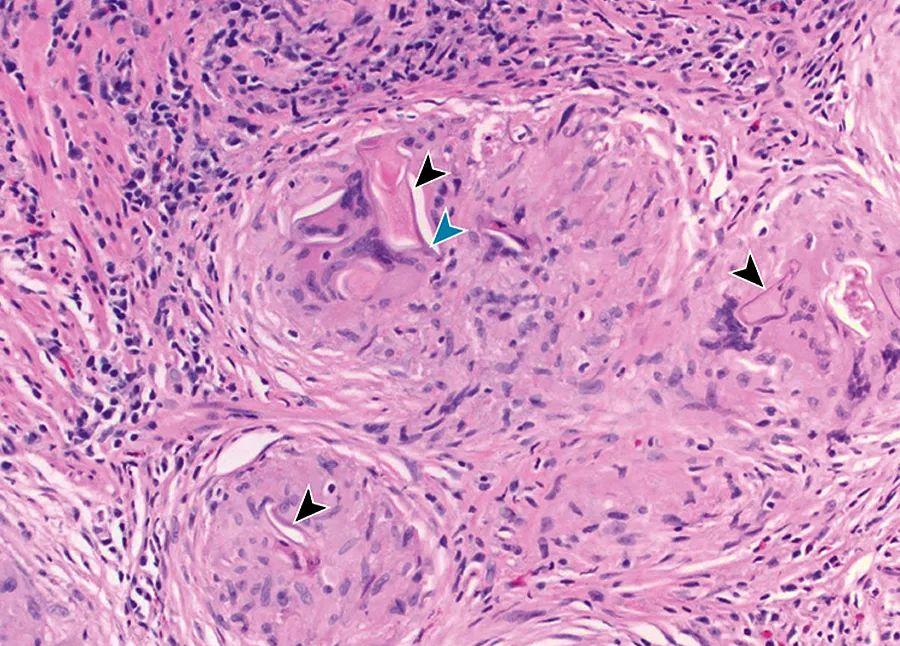

Rectal tissue biopsy; histopathological features are shown.

What's next?

A Praziquantel therapy

B Fecal parasite testing

C Interferon-γ release test

D Antituberculous therapy

===============

diagnosis

schistosomiasis

The key to a correct diagnosis in this patient is histopathology findings of granulomas (black arrows) and lateral spines (blue arrows) containing schistosomiasis eggs, consistent with Schistosomiasis Mannsii. Praziquantel is an effective therapeutic agent (option A). Stool microscopy (option B) is less likely to reveal the pathogen. Pathology confirms the presence of schistosomiasis eggs, excluding tuberculosis as the cause of granulomatous inflammation, so tuberculosis testing (option C) and treatment (option D) are unnecessary.

The patient was treated with praziquantel for 1 day, and the symptoms disappeared. After 1 year of follow-up after treatment, there was no recurrence of blood in the stool.

Case review

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic infection caused by trematodes. Found in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, S. Mansia stupa species parasitize mesenteric venules and generate an immune response to pellets deposited in these organs, leading to intestinal, liver, and/or lung disease. By wading through contact with the infection, the larvae are infected through the skin. In one study, 17% of people exposed to the waters of Uganda's Nile developed acute schistosomiasis.

Chronic schistosomiasis is more common in individuals in repeated contact and is characterized by granulomatous inflammation that can progress to tissue fibrosis. Schistosomia mans eggs are deposited in the intestinal wall, liver and lungs. Bowel disease often presents with diarrhea, which can be bloody or can lead to acute appendicitis. Of the 304 surgically treated appendicitis in South Africa, 10% had histopathological evidence of schistosomiasis. Advanced colonic involvement can lead to intestinal stenosis or protein-loss bowel disease. Liver involvement can lead to hepatosplenomegaly and abdominal pain. Chronic liver infection can lead to peri-portal fibrosis, portal hypertension, varicose bleeding, and ascites; pulmonary involvement can lead to pulmonary hypertension.

For doctors in non-endemic areas, schistosomiasis may not be considered. Checking the stool for eggs is the first step, but this method has limitations. The eggs do not fall off in the excrement until 2 months after the initial infection, and the shedding changes over time, affecting the results of stool microscopy. In endemic areas, a single sample had a low negative predictive value. When the prevalence of the disease > 20% or the degree of clinical suspicion is high, the diagnosis results of multiple sample examinations increase, but it is still possible to miss the diagnosis, especially in returning travelers, where the parasite load is usually low. In a study of travellers returning to the UK, microscopy detected only 45% of cases. Colon biopsy is usually diagnostic, and when the diagnosis is uncertain or schistosomiasis is suspected, indications are present despite a negative microscopic examination. Serology cannot distinguish between active and previous infections because antibodies can persist for years after infection.

Praziquantel is the treatment of choice. Praziquantel does not work for immature worms, so return travelers should receive treatment 6 to 8 weeks after their last exposure to contaminated water, otherwise, a repeat course may be required. If persistent symptoms or eosinophilia occur after treatment, a second course of treatment should be carried out. When microscopic eggs are positive, they should be repeated 1 to 2 months after treatment to ensure eradication. If the eggs are seen again, another course of treatment is required.

answer

What's next

A. Praziquantel

===================