Written by | Zhang Meng

In the early 1940s, during the Soviet anti-fascist war, Pasternak was evacuated with his family to Chistopol. His main job at the time was translating the literature of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller, and it was during this time that Romeo and Juliet was completed. By the way, Pasternak's translations of Shakespeare and Goethe are still unparalleled in Russian translation; however, in his free time, he composed a number of poems related to the war. To his chagrin, these poems, unlike the simple and easy-to-understand texts of Simonov and Tvaldowski, did not gain widespread popularity during the Soviet Union's wartime. In fact, Pasternak was already preparing to write novels at that time, and as early as the 1930s, he said in a letter to Gorky that he was more eager to write in prose. After several unfinished semi-finished works, he completed The Doctor Zhivago, which later won the Nobel Prize, between 1946 and 1955.

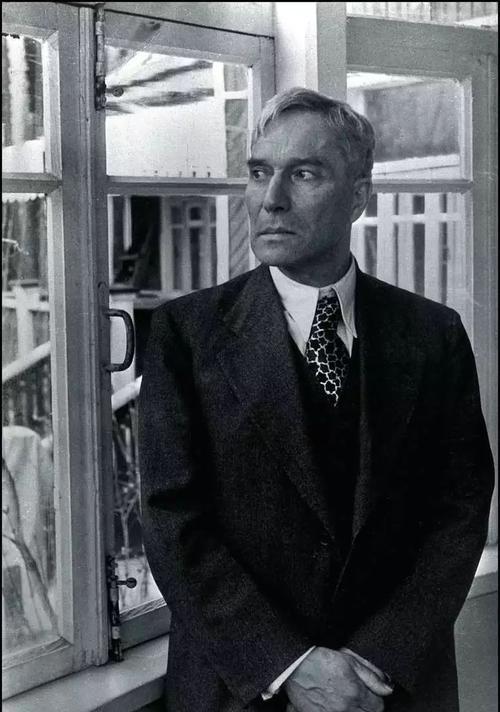

Bo Pasternak (1890–1960) was a Soviet writer, poet, and translator. Born into a family of painters. He is the author of a variety of poetry collections and translations. His masterpiece "Doctor Zhivago" won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Literature.

1. "Miracles" are the most important component of Doctor Zhivago

The love of "storytelling" was evident at an early age in Pasternak. According to De Bekov's Biography of Pasternak, once, in a dark room, Boria (Boris's nickname, Pasternak) told the story of a "Bluebeard" and made his brother "utterly stupid." Seeing that her brother's soul was about to be frightened, Boria regretted it. At that time, he believed that he had the superpower to infect other people's emotions; and narrative works were undoubtedly the best way to achieve this superpower. In Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak established for himself several qualities as a storyteller, one of which was the pursuit of "miracles."

In Bekov's view, "miracles," or "coincidences," are the most important components of Dr. Zhivago. Pasternak uses these techniques extensively, making them as prominent as possible, and with a sense of personal pleasure, stacks all kinds of contingencies and gives them rhythm. He even believes that in addition to these "crossovers of fate" in the work, the entire novel is "only left with the praised scenery, plus a few aphorisms". Bekov seems to be exaggerating here, but turning to this novel, there are indeed many such "crossovers of fate", the most typical of which may be the description of "winter nights".

Doctor Zhivago, by Boris Pasternak, translated by Lan Yingnian Gu Yu, Edition: New Classics| Beijing October Literature and Art Publishing House, April 2015

On Christmas Eve 1907, Zhivago and Tonya took a sleigh to Svenditsky's house for a Christmas party, and on Karmegorsky Street, Zhivago inadvertently glanced at the window of a family, "the window flower was melted into a circle by candlelight." Candlelight poured out from there, almost a gaze of conscious gaze at the street, and the flames seemed to be spying on passers-by, as if waiting for whom. The scene shook his heart, and he was instantly inspired to whisper, "A candle is lit on the table." Light a candle" verse. Zhivago, as the protagonist, and Pasternak, as poet and author, are linked here—a verse that later appears at the end of the book and becomes the subject of the poem Winter Nights.

Far from over, Pasternak arranges a plot unknown to both parties: on that Christmas Eve, at the moment when Zhivago was staring out the window, Lara was in the room confessing her heart to her future husband, Andipov. "The room was sprinkled with soft candlelight. On the window glass near the wax head, the window flower slowly melts into a circle. "The hero and heroine, who were originally in two time and space, were gathered together by candlelight.

Eighteen years after this scene, Zhivago and Lala experience the wash of the torrent of the times, experience love and separation from each other, and return to Moscow when the Creator/Author once again arranges the plot of the reunion in their hometown. Zhivago was destined to live in this room unknowingly and die here. When Lala revisited her homeland and stepped into the room again, she unexpectedly found the coffin placed in it, and inside lay her lover Zhivago. Lara couldn't help but recall that she had been here and had a heartfelt conversation with her future husband, but she couldn't imagine that the candlelight that night was no stranger to Yura(Zhivago).

How could she have imagined that the deceased lying on the table had seen the window opening and noticed the candle on the windowsill as he drove through the street? From the moment he saw the candlelight outside—"candles lit on the table, lit candles"—and decided the fate of his life?

The narrator's omniscient perspective here is obvious: the fates of Zhivago and Lara are full of coincidences and contingencies, and it is difficult to say that they are real characters in real life. The hero and heroine will meet several times inconceivably, and not only that, but when the political fate suddenly changes, Andipov will also meet Dr. Zhivago and talk to him and tell him the condemnation of his conscience. Such coincidences are too deliberate, and they have deviated from the track of realistic novels several times. In the view of the scholar Vlasov, "Doctor Zhivago" is "a combination of objective epic narrative and subjective lyrical narrative"; reading its subjective lyrical part reminds people of the thrilling-legendary plot techniques used by Romantic Western writers, as well as the "no coincidence is not a book" in traditional Chinese novels.

The Biography of Pasternak, by de Bekov, by Wang Ga, Edition: People's Literature Publishing House, September 2016

Countless counterintuitive encounters and reunions can continue from the beginning of the novel to the end of the protagonist's life. On the tram where Zhivago died unexpectedly, he saw an old lady sometimes walking behind the train, sometimes catching up, and couldn't help but think about the math problem he used to do at school: when two trains that had departed at different speeds would meet. From the problem of catching up with two trains, he went deep into the question of the situation of life: a few people who rushed to the road had a first and a second, what makes some people always have better luck than others, and some people catch up with others in lifespan? Obsessed with this philosophical contemplation, Zhivago did not notice that the old lady outside the tram was miss Frieli who had brokered him and Lara in the city of Melyuzeev, and what he did not expect was that soon he would die suddenly in the car, and the old lady eventually surpassed the tram for the tenth time, but she herself did not expect that she had surpassed Dr. Zhivago and had far surpassed him in life.

This deliberately arranged plot is in line with the psychological motivation of the storyteller—pasternak's initial setting of readers is not an elite intellectual, but a mass reader in the Soviet Union and the world. To write a novel acceptable to the average reader is a somewhat naïve idea of Pasternak, who had once been a Futurist poet. He aspires to make readers feel the "rift" of time and space here through disassembly and aggregation, and to experience the thrill of reading legends or fairy tales. Just as the protagonist in a fairy tale experiences a sharp change in situations and the inconsistency of time and space, Pasternak also makes his characters experience this adventure from time to time, thus giving the reader an experience similar to solving puzzles: since the context of the revolution has become so turbulent and changeable, "miracles" naturally become variables within reason.

2. Very "modern" narrative perspective

Pasternak has a passion for how to tell a "magical" story. According to the writer's son, Pasternak had conducted a systematic study of fairy tale theory during the creation of Doctor Zhivago, and he had also carefully read Propp's book "The Historical Roots of Magical Stories". This makes many readers blinded by some seemingly traditional narrative threads when they start "Doctor Zhivago", thinking that it is a continuation of a classic work of the 19th century, but in fact, Pasternak is a storyteller in the modern sense, which is a modern novel wrapped in the cloak of "Russian fairy tales" or "folk myths", and to understand the coincidences, metaphors, symbols and other narrative means, the reader needs to spend as much energy as understanding Kafka, Joyce, Proust put in the effort.

"Novel< The Narrative Art of Dr. Zhivago's >, by Sun Lei, Edition: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, December 2019

Pasternak's storytelling perspective, for example, is very "modern." In Sun Lei's monograph "Long Novels< The Narrative Art of Dr. Zhivago's >", the narrative perspective of this work has been examined, and it is believed that the entire work presents multiple perspectives of transformation, interweaving and echoing, which is very different from the traditional "protagonist perspective" or "God perspective". The plot of Lara's husband, Strynikov (Andipov), shelling the town where his wife and daughter live is told three times, but from a different perspective.

The first depiction uses an omniscient perspective to reveal the inner activities of Strelinikov (who at the time Pasternak had not yet revealed to us that he was Andipov) before the bombing. The revolutionary sentiment of meritorious service eventually led him to give up his children's love and make a move of "great righteousness and annihilation of relatives". The narrator, pretending not to know Strelinikov's true identity, does not comment on the matter, saying only that "the revolution gave him an ideological weapon." The second depiction was in Lara's conversation with Zhivago. Through Lara's perspective, the reader reads her incomprehension and complaints about her husband's behavior, "This is something I can't understand, not life... In addition to principle is discipline..." The reader will have a strong identification with this condemnation; and at the end of the Soviet-Russian Civil War, When Andipov fled the ranks in order to escape political purges, he met Zhivago unexpectedly, and in his confession, the shelling plot appeared for the third time, and the reader's evaluation of the matter turned again to find the real culprits who caused the "man-made disaster": the brutal war and the ideological politics that destroyed human nature and human feelings. In this way, Pasternak echoes through three perspectives, so that a character's personality characteristics and life forms are three-dimensional.

In addition to the above discussion, many scholars today have also made in-depth analysis of the mythological and biblical structure of the novel and the folklore characteristics of the novel, believing that this is the performance of "Doctor Zhivago" across the boundaries of the times. But readers at the time didn't pay much attention to these experimental writing techniques, and they could read more about the "cloak" of Russian folk tales and European adventure novels. They accuse these "miraculous" and repetitive arrangements of being old-fashioned, and pasternak's storytelling tone is always a little unfriendly. The scholar Mikhail Pavlovic said that Pasternak was greatly influenced by Tolstoy in the writing of novels, and he also hoped to be able to have the identity of a mentor "preacher" when telling stories, eager to use his life experience to attract readers through the disguises of coincidence, repetition, and adventure, and then discuss with him the most important themes for writers: about Christ, about faith, about the meaning of immortality and life. However, he lived in a time no longer of the late 19th century, and "after the wars, after the Gulag, Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, for many, that desire for a wise mentor has become anachronism." ”

3. Awakening fables full of metaphors and exaggerations

Among his contemporaries, there were not a few writers who sharply criticized Doctor Zhivago. In addition to the closely related female poets Akhmatova and Chukovsky, the pro-Soviet Sholokhov even believed that there was no need to ban the book in the Soviet Union. It is incumbent upon readers to generally understand how poorly this one is written. An important anchor in all the accusations is the questioning of Pasternak's ability to narrate. For example, the writer Nabokov unceremoniously describes the protagonist of Doctor Zhivago as "a sentimental doctor with a vulgar mystic desire, with a vulgar cycle of vulgarity in his speech." Apparently, Nabokov also despised the "miracle" plot of the novel.

Speaking of Sholokhov's suggestion above, in fact, in the context of the Soviet Union's prohibition of the publication of Doctor Zhivago, a section of the eleventh chapter of the novel, "The Soldier in the Woods", was still printed in the Journal of Literature; of course, it was followed by negative comments from the editorial board of the magazine New World, which Pasternak had originally contributed. It was published not to show official magnanimity, but to better demonstrate the novel's intellectual toxicity. Interestingly, the published passage also deals with the plot of the "miracle": Zhivago is forced to join the guerrillas, despite his extreme reluctance – the doctor has no right to carry weapons under international agreements. He sympathized with the White Army soldiers across the trenches, believing that they had received the same education as himself, and was full of sympathy and understanding for them. But he had to pull the trigger again when the enemy was on either side, so he aimed his gun at the dead tree and fired. Even so, someone was wounded under his strafing, and a young warrior was "killed" by him. After the fierce battle, Zhivago walked over to check on the warrior who had fallen under the gun, and accidentally found that his shot hit the amulet on the warrior's chest, thus saving him...

Such a coincidence, which is less than one in ten thousand, was encountered by Dr. Zhivago. He longed to be a neutral man on the cusp of the revolution, and such neutrality seemed unattainable. So the narrator finds a "miracle" for him, saving him from the condemnation of his conscience. It was also by virtue of his "miracles" that Dr. Zhivago survived all the chaos and returned to Moscow, preserving his poetry. At this time, the protagonist's mysterious brother Major Yevgraf Zhivago descended from the sky to help his brother collect and preserve all the poems, and eventually these poems were handed over to Zhivago's friends, and only then did they have the posthumous works that were later published... Pasternak himself explains these "arbitrary coincidences" as follows: "I want to show the freedom of existence and the almost unbelievable realism." ”

His claim seems unconvincing. However, it is impossible for an unarmed intellectual with humanistic ideals to survive in the age of great upheaval, to preserve as much as possible the ill-timed poetry, and not to resort to surreal "miracles". Bekov defines Doctor Zhivago as a satirical fable full of metaphors and exaggerations. It seems implausible because of these coincidences and chances, just as life in the midst of a mysterious historical turn. In other words, with the help of those "miracles", Pasternak hopes to cross the "impossibilities" of reality and present the "possibilities" of the spiritual world in an ideal state.

The author | Zhang Meng

Editor | Zhang Jin

Proofreader | Li Xiangling