The original author | Anthony McGowan

Excerpt from Xiao Shuyan

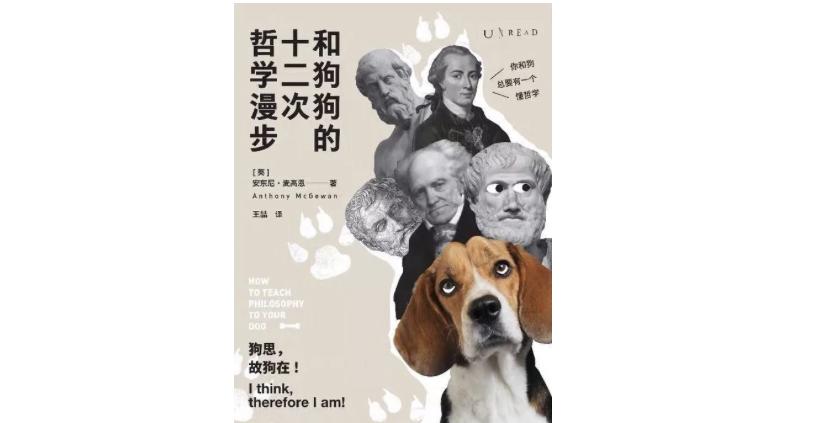

Twelve Philosophical Walks with Dogs

Author: [English] Anthony McGowan

Translator: Wang Zhe

Edition: Unread 丨 Tianjin People's Publishing House, November 2020

I have a dog named Meng Di, a scruffy Maltese dog. Meng Di looked like an incompetent white cloud that had fallen to the ground and was still rolling in the mud for a while. His eyes are black, his eyes are elusive, his nose is black, his moustache seems to have been smoked, and he is not dark, because he always likes to sniff and sniff at the scented horns, and this "horn" can refer to both body parts and geographical locations.

In terms of intelligence, the Maltese is often described as "mediocre": slightly clumsy compared to the always-alert poodle and the Collie Shepherd who can play chess, but more than one notch higher in IQ than the boxer dog that stares at the tennis ball all the time, hoping that it will survive, and the Afghan hound who is like a drug and racking its brains to prevent itself from swallowing its tongue. Meng Di will not play tricks, tell him to "come", useless, he will not even listen to "sit down", but he will quietly wait for you to walk towards him, as if there is nothing more interesting in the world.

Although I was a little harsh on Meng Di's intellectual achievements, he always had a serious and doubtful expression, as if he was trying to solve a certain set of codes in an orderly way, or seriously thinking about the hidden meaning of the universe.

I never saw a dog in a Western philosophical work until I took the initiative to look for it. Suddenly, I found them all over the place, sometimes lurking between the lines, as if I knew I was in trouble by spitting up or stealing food in a cupboard, while other times it was hiding in broad daylight.

Given the long-standing intimacy between humans and dogs, it's no surprise that dogs seep into every aspect of our intellectual culture, myths, stories, and philosophical explorations. Archaeologists have found it difficult to determine when dogs were domesticated, although the best guess is thirty or forty thousand years ago. It is likely that it was the wolf that first wandered around the dwellings of our ancestors, and then over tens of thousands of years the part of the wolf pack that resembled our modern dog diverged, a process that was produced by a combination of natural selection and artificial breeding.

Fifteen thousand years ago, we could not farm, but people and dogs were already dependent on each other. The earliest ironclad evidence of the coexistence of humans and dogs was unearthed in a German quarry, where three Paleolithic remains: a man, a woman, and a puppy were buried together. This dog had suffered from canine distemper, and only under human care could it live that long. This dog is too weak to be used for hunting, so it must have other uses in group life: it is a pet...

Looking at ancient and modern times, dogs have been revered in most human cultures. In pre-Columbian America, the Mayans and Aztecs believed that dogs were the guides and guardians of goodness, leading the dead to the world of souls. The Egyptians may be better known for their love of cats, but dogs are often buried with their owners and mummified. To this day, the first animal with a name was a personable hound named "Abuwtiyuw" (I don't know how to pronounce the name), which lived during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt (2345-2181 BC).

Stills from the anime 101 Loyal Dogs.

Looking a little closer to the time and place of the Western philosophical tradition, the Persian Zoroastrians were deeply attracted by the wisdom and integrity of the dog. The Persians believed that dogs would guard the bridge where the dead could go to heaven, which coincided with Mayan mythology. Dogs are also the main participants in the eternal battle between light and darkness, under the good god Ahurah Mazda, fighting insects, slugs, rats, lizards, frogs, and probably cats under the evil god Angra Manu. The reason why dogs stand still and stare quietly at the void in front of them is precisely because they can see evil spirits that we can't see. Therefore, if we mistreat our strong allies in this great war, we will be severely punished in this and future lives. Dog killers have to do many things to atone for their sins, including killing ten thousand cats. So, yes, Zoroastrians are undoubtedly dog lovers...

Looking a little closer to the origins of philosophy, the heroic age of Greece appeared with Odysseus' loyal hound, Argos, who waited for twenty years for its owner to return home. Once walking like a fly, it is now lying on a pile of dung, hungry and tormented. But the whole of Isaki, and only it recognized Odysseus. The compensation it received was the hero's tears, and finally swallowed happily. But from another point of view, if the hero of Homer's epic is defeated, the greatest shame is to be stripped of his armor on the battlefield and thrown bare-chested to feed the dogs.

Up to now we have discussed history, myths, legends, but our first dog, which is entirely philosophical, did not appear until plato's Republic. In The Republic, Plato attempts to define justice (and many other things) and establish a set of standards for a perfect society. A key component of the ideal government is the guardian class, the philosopher warriors who lead and protect the state. What qualities should a Guardian possess? They must be kind and merciful to their people and merciless to their enemies. Where can these qualities, which contain true knowledge, be found? The answer is that it can be found in domestic dogs, which can know good and evil and distinguish between friends and foes by intuition alone, and they will lick the hands of their owners and drinkers, even if they know nothing else, but show no mercy to unwelcome invaders.

This nature of it is indeed fascinating;

Is a true philosopher.

Why?

The basis is that dogs distinguish between friend and foe entirely by whether they know it or not. How can an animal distinguish between likes and dislikes by knowing and not knowing, and say that it does not like to learn?

Indeed it is.

Isn't love of learning and love of wisdom a philosophy?

Stills from the movie "The Story of Hachiko the Loyal Dog".

Our philosophical dog debuted in this way, and it was indeed decent. But Plato's view of dogs is not always praised, and he will directly call those who disagree with him as "dogs". This brings us to the most famous dog in the field of philosophy. Today the word cynicism (the Greek word for dog) means in the Oxford English Dictionary: "A man who does not believe that man's motives and actions are sincere or good, and always expresses his views in a mocking and sarcastic way; ”

What is described above is not a positive image: a thin-lipped world-weary man who ridicules the kindness of others and constantly tears off the mask of morality and exposes the hypocrisy behind it. The modern meaning of the word is clearly embodied in the original cynics, who were a group of wandering thinkers, in the same era as Plato, but took a very different path. The cynics live simply, regard wealth and worldly success as dung, wear torn clothes, use heaven as a quilt, and use the earth as a bed, and curse the greed and materialism of the rich. Question all customs and ridicule all moral or religious traditions. But the essence of cynicism is to strive for a virtuous life, and the critique of cynicism, as destructive as it is, remains an indispensable first step toward enlightenment.

What does this have to do with dogs? There are several different versions of the origin of the name Cynicism. Probably because the first cynic, Antisty, lectured at a stadium called the Land of the White Dogs. And I'm more inclined to another story, where Plato, because he has always been provoked and teased by the greatest cynic, Antisthenes's disciple, Diogenes of Sinopa, scolds: "You are a dog!" "It amuses Diogenes, who is very happy to be a dog. A dignitary threw a bone at Diogenes and cursed the same thing, and Diogenes raised one leg and peed on the other side. In fact, Diogenes did look a little silly, and he was notorious for listening to lectures and eating loudly and farting unscrupulously during conversations with others. He's either picking teeth or provoking disputes. If he walks into the "quiet carriage", it will become a nightmare for everyone... And he'll be at ease. On one occasion, Diogenes wiped his dirty feet on Plato's beloved carpet and said, "I am trampling on Plato's vanity." Plato cleverly replied, "Diogenes, how arrogant you are to pretend not to be arrogant." This was Plato's only counterattack victory.

The main reason why cynics are labeled "like dogs" is that they have a widely criticized feature, that is, they are not ashamed of their physical functioning. Diogenes would defecate on the ground, and his disciple Klaters of Thebes went further, doing things directly in full view of everyone with his wife Hipparchia. Maybe that's why "fighting the field" is called doging in English.

Krates and Hipparchia lived long enough to sleep at the gates and colonnades of Athens. Their mentor Diogenes lived longer, and it is recorded that he lived to be in his nineties. Finally, the dog reappeared. There are several different versions of Diogenes' death, one saying that he held his breath for many days (which basically achieved his goal); another more banal version is that he ate raw cow's feet and died of food poisoning; and another version is more in line with this cynicism: it is said that Diogenes was bitten by a dog while giving his dog an octopus, and then the wound festered and died; and another is that he was infected with rabies by his dog.

In fact, Diogenes was not the first philosopher to die of a dog. Heraclitus was one of the first philosophers and died particularly tragically. Heraclitus was a nobleman, particularly disgusted with commoners, believing that only a few could understand the truth of what he was saying. He said that the superiors were always ready to give up everything in pursuit of immortal glory, while the masses, like cattle, thought nothing but knew how to eat and drink. His fate, if not deserved, is more or less in line with his own. He developed edema and applied cow dung to treat himself, believing that cow dung could suck away excess water. At this moment, a group of dogs found him and ate him because they did not recognize him as a human.

For the next two millennia, the presence of dogs in philosophy was relatively rare, and ironically, philosophy during this period was under the domination of Plato's great disciple Aristotle, who was a very dogmatic man. By the time of the post-Renaissance, philosophy had awakened and the dog had returned.

A dog appears alone in Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, one of the greatest and most difficult works of Western metaphysics. In the following strolls we will mention Kant many times, but for now we need only know that in the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant tries to bridge a protracted divide in the history of philosophy while criticizing: there is a school of philosophers who firmly believe that knowledge comes from pure thought, while the other claims that we can only acquire knowledge that reaches the mind through the senses. To explain that the gap between ideas and sensory experience can be filled, he gives the example of a dog.

The concept of the dog indicates a law by which my imagination can trace, depict, or draw the general outline, figure, or shape of a quadruped animal, without being limited to any single or individual shape provided by experience.

Without the concept of a "dog," Kant said, the wide variety of sensory perceptions—ears, fur, hunched tongues, upturned legs—would disappear in the background noise. The idea of "dogs" is ingrained in our hearts enough to unify the fragments of the world before us and shape them into familiar friends and partners. But the word is still vague, and both the annoying little chihuahua and the arrogant Great Dane can be included.

We mentioned Wittgenstein earlier and talked about how he figured out the meaning of words in a web of language and social practice. Communication involves engaging in a series of intertwined "language games" that our knowledge of these different language games makes communication possible. As Wittgenstein explores the boundaries of "meaning," he mentions a confused dog several times—a dog that seems to have been trying to be human. But because it lacks the necessary ability to understand proper wordplay, it is neither hopeful nor fearful of the future. And dogs don't lie.

Like any other language game, lying is a language game that must be learned to be able to... Why don't dogs pretend to be in pain? Is it too honest? Can a dog teach a dog to pretend to be in pain? Perhaps, one can teach it to cry out on a particular occasion as if it were painful, though it did not hurt. But the environment required for this true pretend act is missing.

On the point that dogs can't pretend to be in pain, I think Wittgenstein was right. But surely even philosophers can't say that dogs don't "feel" pain, right? My last example of a philosophical dog can be unpleasant, but it can also be instructive. We have to go back to the seventeenth-century works of René Descartes. Descartes is notorious among animal lovers because, in his view, all non-human animals are nothing more than "natural automata," soulless mechanical devices that cannot think, feel emotions, or feel pain.

There are two often mentioned descartes anecdotes, both of which point to the consequences of his theory. One day, while strolling with his friend, the philosopher caught a glimpse of a pregnant dog. At first, he went up and scratched the dog's ears and cared for it. Then, to his companion's surprise, he kicked the dog in the stomach. Then he began to comfort his frightened and sad companions, explaining to them that the dog's wailing was nothing more than the friction of a gear, because animals do not feel pain, and they should leave this sympathy to the suffering humans.

Another, more horrible anecdote was related to his wife's pet dog. The philosopher was inspired to read about William Harvey's discovery of blood circulation and was determined to explore and observe it for himself. He waited patiently until his wife and daughter were out on business, and he picked up the little butterfly dog (the kind of dog with big ears like butterfly wings) and took it into the basement, where a terrible vivisection was performed.

As for how Descartes' wife and daughter reacted when they returned home to find the body, history does not record it.

Why is there no historical record? For Descartes had neither a wife nor a daughter. The philosopher never married. This story is completely fabricated, fictionalized by the heat of the hellfire of network stupidity. But the horrors described here did happen some two hundred years later. The perpetrator was claude Bernard (1813-1878), a well-known nineteenth-century anatomist who would unload live, conscious, unanesthetized dogs (and rabbits) into eight pieces. He was indifferent to his wife, and he actually dissected her puppy. So, the wife's anger can be imagined, she left Bernard and founded an anti-animal abuse organization. The reason why this story is put on Descartes' head is because he thinks that animals are automata.

So, what about the story of the pregnant dog? If so, it was the later French philosopher Nicolas Malebrances (1638-1715). Similarly, because Descartes was so famous, such stories are related to him.

Almost, the dog in the field of philosophy has said enough, now, let's let our dog learn some philosophy too!

Written by | Anthony McGowan

Excerpt from | Xiao Shuyan

Editor| Li Yongbo

Proofreader | Li Xiangling