Hello everyone, here is the book slip column, this issue continues to explore with you the late Greek doctrine. Pi Lang, No. 4 (Philosophy: Everything you say is true, but I just don't necessarily believe it), No. 13 (No.13 The Origin of Lofty Ideals, the Ethics of the Stoic School) and No. 14 (No.14 Is the Stoic School, which claims to obey the laws of nature, really so "natural"? Introduced the late Greek Pilangism and the Stoic School, respectively, and in this issue, I will share with you The Epicureanism known for its "happiness" and "pleasure".

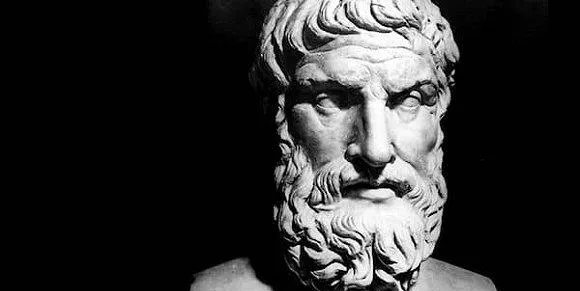

Epicurus

As stated in previous periods, the turbulent social environment forced philosophers to think about ethical questions such as how to live happily, so both the Epicureans and the Stoics needed to point out what happiness was in their view, including how the world worked, what happiness was, how to recognize this happiness, and how to achieve happiness. This kind of question makes the Doctrine of the Epicureans and the Stoic School equally cover the fields of ontology/metaphysics, logic/epistemology, and ethics, in order to answer the above questions separately.

Metaphysically, the Stoic school inherited Heraclitus's fire origin and logos doctrine, while Epicurus inherited Democritus's atomism, which holds that the world is made of atoms, that the atoms themselves have weight, that is, they are doing irregular falling motion, and the collisions between different atoms produce such a kaleidoscopic world. In epistemology/logic, the Stoic school promotes logical inference, inheriting the tradition of Aristotle dialectics; the Epicurean school further carries forward the doctrine of Democritus, the "great rebellion" of advocating sensationalism, that the source of knowledge is the feeling, that sensory perception is the basis of correct understanding, what we see, smell, taste, and feel is true, bringing about the fallacy of Plato's "opinion", only because the judgment is wrong, not the feeling is wrong, This is very similar to empiricism in modern philosophy.

Since this metaphysical and epistemological basis exists, it is also determined that the ethics of the Epicurean school are very different from those of the Stoic school. Under metaphysical derivation, the world itself is composed of disordered atoms, so the idea of "fate" and predestination is naturally untenable in The Case of Epicurus. Everyone's life is their own life, randomly, accidentally born, and randomly, accidentally died, not like the Stoic school said that "life is like a stage", then everyone has the right to decide their own life and change the trajectory of life. At the same time, from an epistemological point of view, the Epicurean school advocates the use of feelings as the basis of understanding, then for the life of the individual, the good and bad of life, nature is also the feeling of good and bad, and feelings also show that people have a natural tendency to be happy and avoid suffering. Thus, Epicurus pointed out that in ethics, good is happiness, and evil is suffering.

Precisely because of the perception of happiness as good, Epicurus's ethics is also called hedonism. From Aristotle to late Greece, the purpose of ethics was to pursue happiness. Epicurus believed that in order to live happily, it was necessary to learn ethics, just as medicine, which cannot cure physical ailments, is a useless art, and philosophy that cannot relieve the suffering of the soul is useless empty words. So, in Epicurus, happiness is the epitome of happiness. The philosophy of seeking happiness is the philosophy that relieves the soul of its suffering.

However, although hedonistic, it is not as hedonistic pleasure as we take it literally. Epicurus believed that human nature tends to seek pleasure, and that each pleasure has its own attraction, but not every pleasure is worth choosing, and likewise not all suffering needs to be avoided. For example, some happiness may be followed by the loss of happiness, or even pain, and some pain may be followed by long-term happiness, in which case the former's happiness is not worth pursuing, and the latter's pain should be borne. In addition to the difference in consequences, there is also a difference in intensity of happiness, and spiritual happiness is higher than physical happiness, and without spiritual happiness, physical happiness is impossible. Epicurus distinguished between different pleasures in two ways to illustrate which pleasures were more advanced and which were more worthy of choice.

One classification is to divide the relationship between need and nature, the lowest natural and necessary pleasures, such as appetite; natural but non-essential, such as sexual desire; and unnatural and non-essential, such as vanity, honor, power, and so on. The other is distinguished between intense but unsustainable dynamic pleasure and calm and long-lasting static pleasure, the former being primarily the demand and satisfaction of desires, such as entertainment and play, and the latter being the elimination of suffering, such as not being hungry, not thirsty, and being carefree. After this distinction, continuing the tradition of Greek speculation, "static" is often higher than "dynamic", because "static" things are often lasting and peaceful, dynamic things are fleeting, such as natural but non-essential sexual satisfaction, after a short period of happiness, ushered in emptiness, as mentioned above, some happiness is accompanied by pain. Moreover, after satisfying one desire, it often brings new expectations for another desire, and in the pursuit of dynamic happiness, the happiness obtained is always increasing or weakening, and the inability to enjoy happiness will bring about the pain of mental uneasiness, and excessive enjoyment of happiness will also bring pain. Epicurus points out, "When I live by bread and water, my whole body is filled with happiness; and I despise extravagant pleasures not because of themselves, but because all kinds of things do not follow." ”

That is to say, the static pleasure advocated by Epicurus requires lasting peace, which is also in line with the ancient Greek philosophy that spiritual values are greater than carnal values. Physically, physical health is needed, and natural and necessary pleasures need to be satisfied, but there is no need to excessively pursue the enjoyment of this kind of tongue-in-cheek desire, in layman's terms, that is, eat less hungry, eat more support, just enough. Spiritually, it requires a prudent life, a quiet attitude towards everything, and an excessive pursuit of natural but non-essential and neither natural nor necessary pleasures.

Of course, this is not to say that Epicureanism, like asceticism, demanded that one lower the broad value of pleasure and simply satisfy simple pleasure. Although static happiness is higher than dynamic happiness on a theoretical level, it does not mean that dynamic happiness is not important. Instead, he argues that the stimulation of dynamic pleasure enriches the experience of different pleasures, combined into his sensory epistemology, which forms personal memories and cognitions that can be used to a certain extent to get rid of suffering. From his point of view, as long as this kind of dynamic happiness does not hinder physical health and peace of mind, then it can be pursued with confidence. He believes that it is precisely because people do not know which happiness is worth pursuing and which happiness needs to be moderate, so it is necessary to treat life with prudence and be cautious about every temptation. Like Aristotle, he believed that "virtue" was important, and that a virtuous person was a man who could weigh carefully in the pursuit of pleasure. Therefore, it is necessary to study philosophy in order to understand things, to understand nature, to understand the happiness that suits man.

The ethics of Epicureanism, in detail, did not share the same world sentiments as the Stoic school. As two doctrines of the same period, if the Stoic school is universally applicable and suitable for social and political practice, then Epicureanism aims to live a happy life in the midst of chaos, and from the perspective of personal self-cultivation, Epicurus's hedonism is beyond reproach.

Unfortunately, as long as all practical doctrines are passed on, they will inevitably be utilitarianized or vulgarized, such as the Stoic school of equality in the world over time became the official ruling doctrine of the Roman Empire, just as Confucianism changed from loving people with benevolence to ruling people with benevolence; and Epicurus's hedonism gradually became an excuse for the hedonistic escape of the children of the poor in the future, and how much like the sentiments of Ji Kang and Ruan Zhizhi of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Forest at the time of Wei and Jin Dynasties, "overstepping the name of teaching and letting nature" and "letting the waves form skeletons, getting carried away with the elephant", The bones of Wei Jinfeng, who did not conform to the dark times, were distorted by posterity as simple debauchery in the inheritance of later generations. Confucianism and Stoicism in Chinese philosophy, metaphysics and Epicureanism, are quite similar in ethics.

Three of the four philosophical schools of late Greece have been introduced to you, and the next issue is announced to usher in the New Platonism of the Trinity. Here is the book slip column, like friends to point a point of attention a thumbs up, we will see you in the next issue!

bibliography:

Zhao Dunhua, A Brief History of Western Philosophy, Peking University Press, 2001

Ti Li, Jia Chenyang Xie Benyuan Translation, History of Western Philosophy, Guangming Daily Press, 2014 edition

Russell, He Zhaowu, translated by Joseph Needham, History of Western Philosophy, The Commercial Press, 2015 edition

Feng Dawen, Guo Qiyong, "A New History of Chinese Philosophy", People's Publishing House, 2004 edition