Black's contemporaries mostly considered him eccentric and mediocre. However, technical weaknesses aside, Blake's innovative approach ranks him among the greatest graphic artists of all time. The William Blackett exhibition at the Tate Britannia, London will run until 2 February 2020.

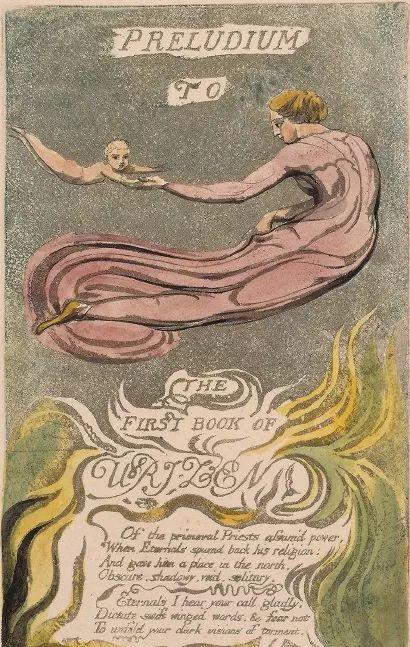

Blake's Mythical Fable The Book of Ullison, Preface Page (1795)

In February 1818, Samuel Taylor Coleridge received a copy of Songs of Innocence, william Blake's first illustrated collection of poems published thirty years earlier. The contents of the book impressed and deeply disturbed Coleridge. "You might laugh at me for calling other poets mystics." Coleridge, who was already addicted to opium at the time, wrote to a friend, "But the truth is that I am only mired in common sense compared to Mr. Black. "Of course, Coleridge is not the only one who has been confused by Blake.

From his nudism, to his self-created obscure cosmology, to his illusion of angels sitting on trees, and to the novelty of political and religious attitudes— Blake's distinctive personality became his shell, almost impenetrable. His weirdness is not a certain part of his personality traits, but his whole self, and it is this that makes people discouraged from him. Blake once said of his illustrated poems, "My design style is a species in itself." Perhaps, Blake himself is best suited to be classified as a unique species.

No matter how Blake is defined—calling him a poet, a prophet, and a sage, or, as the poster at London's Tate Britannia, dramatically declaring him "Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary"—Black was first and foremost a professional artist. For most of his life, he was a well-respected sculptor who opened his own business. He dedicated his evenings to watercolors and relief etchings—both best-selling works of art—and it was only in his quiet moments of the night that he became a poet and wrote sporadic fragments.

Happy Day (circa 1795) is an ecstatic version of Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvius

Traditionally, artists and poets have been inextricably linked. Blake's illustrated poetry collection and the relief technique he created in his illustrations also stemmed from the limitations of publishing techniques at the time. However, many of Blake's contemporaries and his supporters were deeply puzzled when they read his works such as The First Book of Urizen (1794), Europe: a Prophecy (1794), and The Book of Los (1795). But even if they can't understand these obscure verses, they can certainly understand the power of the pictures that accompany these words. Blake knew the illustrations were profitable, so he would sometimes delete the text and sell the album as a standalone work of art. Without words, these pictures can reflect universal themes. For Blake, his vision was not pure and sacrosanct.

Blake adopted the same principle of pragmatism in creating some of his works on mysterious themes. In the last decade of his life, he created 100 sketches of phantom figures. John Varley was Black's most important patron in his later years. Wally was not only a master of English watercolor painting, but also an astrologer of spiritualism. Every night from ten o'clock until three o'clock in the morning, the two will have a psychic (during which Timei will always fall asleep). Wally would have Blake draw down the ghostly image he saw in the astral realm. Blake painted figures such as British historical figures such as Watt Taylor, King David, and Solomon. Importantly, Wally would buy these drawings from Blake.

William Blake, Dante and Virgil Near the Angel of Purgatory (1824–7)

During a psychic, Wally asks Blake to keep an eye on William Wallace's ghost, and it doesn't take long for Blake to find him. "Right there, he's there, how noble he looks—get my pen and paper!" Blake began to paint as he shouted, but stopped again. "I can't finish it, Edward I is in the way of us." "I'm really lucky," Said Wally, "because I also want a portrait of Edward I." According to the painter John Linnell, Wally "believed in the reality in Blake's vision more than in Blake himself... It was Wally who inspired Blake to see or imagine portraits of historical figures. Blake, in Linnell's words, "a man who smiles at the absurd," certainly enjoys taking advantage of the sincerity and trust of his patrons.

One of Blake's most famous works, The Ghost of a Flea (1819-1820), was born. At one point, Blake told Wally that he had seen the ghost of a fleas, but could not draw it: "I wish I had painted it at the time, and I should have painted it if it appeared again!" "Behold! He looked eagerly into the corner of the room: "It's there, bring me pen and paper, I have to look at it." It's coming! It spat out its tongue impatiently, holding a cup full of donated blood, its skin golden and green, covered with scales. "Whether he saw it with his own eyes or joked with his heart, whether he was for money or whether it was true or false, the monsters he wrote were indeed disturbing.

William Blake (1757–1827)

Blake's artistic career can be said to have long sought recognition. Born in 1757 in a well-to-do family in London's Soho district, he aspired to become an artist early on. He was first encouraged by his parents to apprentice under the sculptor James Basire, and then immersed himself in rubbing at Westminster Abbey. In 1779, he entered the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) and received formal fine art training, first to learn sculpture sketching, then to paint models, and he also received training in the traditional arts of "history painting" (depicting scenes from history, biblical stories, Shakespeare literature and classical mythology) as the primary form.

Although Blake's love of Gothic art and Michelangelo (then less famous than Raphael) led him to disagree with Joshua Reynolds, the dean of the Royal Academy of Arts, he never questioned the excellence of the Academy's first-rate style. Throughout Blake's career, his work has never focused on secondary subjects such as portraits or landscapes, and his paintings can be seen as a variation of "history painting."

Around 1809, Blake spoke of his own view of art. "Oil painting is painting on canvas." He said, "And the engraving is a painting on a copperplate, that's all. Painting is an execution, nothing more, the best painter must be the best artist. "Despite Blake's high-quality training, he was never the best artist. He aspired to create frescoes and altarpieces, and to return art to Michelangelo's grandeur, power and originality. However, his own painting techniques are very basic, his understanding of technique is also very one-sided, and his paintings rarely exceed a page. As a draftsman, he also had limitations: his painting style was too pretentious—his body shape was too slender, his head depicted without obvious characteristics, and he had little interest in the combination of proportions, joints, and angles.

Blake's illustration of Thomas Gray's Eton Overlook (1742).

Inevitably, Blake's peers would have thought he was eccentric and mediocre. In 1809, he designed an illustration of Robert Blair's poem The Grave, and after a small success, he held a solo exhibition on the top floor of his brother's menswear store in Soho. "If art is the glory of a nation," he wrote, "if genius and inspiration are the most important origins and bonds of a society, the people who can best understand these truths will affirm my work and let me do my utmost duty to the country through the exhibition." No one shared this view with him: very few people came to see the exhibition, he failed to sell a painting, and the only comment was hostile, and the critic declared that the works were "wild catharsis of an unsound mind."

Blake is often described as a school of its own, an innovative and independent outsider, a prophetic form with no glory to speak of. In a way, that's who he is, but it also needs to be considered. Black was by no means the only artist of his contemporaries who was full of imagination and had a distinct style. In his art circle, Henry Fuseli, James Barry and George Romney were able to produce eccentric and powerful works, while Fuseley and Blake's classmates at the Royal Academy of Arts, John Flaxman, had a profound influence on Blake. On the European continent, Goya, a true master of art, shows her inner world full of waves through disturbing images. In Denmark, Nicolai Abildgaard's work sometimes reaches the same intensity. There is also the German painter Philipp Otto Runge, whose ideas are also mysterious.

If Blake's religious mysteries—those strong, anthropomorphic figures (e.g., Urisson, Los, Anissamon, and Thiel), a mixture of Christian, classical, and Norse mythological themes—belong to him alone, some of his perceptions of politics and society resonate more broadly. He was against slavery, against mainstream sentiment, he didn't trust orthodoxy, he didn't trust disenchanted science, he believed in individual freedom (including a degree of sexual freedom), all of which made him slightly embarrassed and not completely out of place in the Georgian era of England.

The Song of Innocence was published in 1789, and in 1794 William Blake produced The Song of Innocence and Experience, which featured two first editions of the covers that he engraved and hand-printed.

Blake's radicalism was by no means rebellious, and even his only feud with authority was not what was rumored. In 1803, Blake wrestled with a soldier. The soldier accused Blake of attacking him and endangering the law and order, claiming that Blake had shouted "The king is going to hell." Soldiers were slaves. When he was sent to circuit court in Chichester, England, magistrates quickly determined that the evidence was forged and acquitted him.

At the time of the episode, Blake lived in a cabin in Fairfarm, Sussex, England, owned by the poet William Hayley, who was commissioning Blake to draw illustrations for his book. Although the two eventually parted ways, Haley was only one of many of Blake's patrons during the first decade of the 19th century, who ensured Blake's economic independence. One of them was Nonetheless, a civil servant who supplied the army's uniforms and patronized Black for twenty years. At one point, Bartz owned more than 200 of Black's works, many of which were in the collection of a girls' school he opened. Black's other admirers and patrons included Earl Egmont III, John Linnell, the landscape painter Samuel Palmer, and a group of herders known as the "Ancients."

Different prints of the poem "Song of Innocence" "The Joy of Babies"

The curators of the black exhibition also want to emphasize that Blake's wife, Catherine, is his most important assistant. She not only took care of the housework, handled the accounts for him, and coped with every economic crisis, but also helped him to emboss and color. They were in an unusual relationship. Blake, grieved by a failed relationship, confides in Catherine. "Do you pity me?" He asked her. When Catherine expressed pity for him, he said, "Then I love you." "The marriage of the two has withstood the test of time, although there is no gap in the middle. In particular, according to the poet Swinburne, on one occasion Black "proposed another wife in an already strained family because of his patriarchal complex." Still, Blake confessed to Catherine at the end of his life: "You've always been my angel. ”

In a way, such an artistic, social and family background makes Blake's work seem even more unusual. In addition to his technical weaknesses, he is considered to be the most outstanding graphic artist, with an intuitive perception of design. Most of his human-centered works are small in scale but visually grand. Of the 300 works Tate exhibited this time, the famous "The Ancient of Days" is shown, which depicts Ullison kneeling out of the sun and measuring the world with a ruler. The painting was originally an illustration of the opening volume of Europe: A Prophecy. In 1827, Blake completed the work in the last days of his life, saying " This is my best work " . Indeed, the painting is brightly colored, deepening the bright red at sunset, and the tone is deeper than Blake's other colored works, and it is arguably the most powerful exemplar. This grandiose work is very small, seemingly able to cover an entire wall, reminiscent of Blake's hero Michelangelo, but it is actually only the size of an A4 piece of paper.

Blake believes that innocence and experience are two opposing states in the human soul, such as the "tiger" in "Song of Experience" corresponding to the "lamb" in "Song of Innocence".

Blake's paintings may have a unique connection to words, mainly illustrations around the Bible, Milton, Shakespeare, Dante and Bunyan, but his greatest innovation was at the visual level. For example, his illustrated picture books, which can be said to be variations of medieval decorative manuscripts, employ the technique of relief etching. He called the technique "Hell Law" and claimed that it was taught to him in a dream by his dead brother Robert. Traditional etching uses acid to burn away the notches, while relief etching (Blake does not leave a detailed description of this technique) burns the metal plates so that the text and design patterns emerge and stand tall. Blake's unique skill was not only relief etching, he was also fascinated by the tempera method, which used egg whites and yolks instead of oil to blend pigments, but could be used simultaneously with oil and ink on peach boards. However, this strange attempt at ancient techniques does not always succeed.

Between 1795 and 1805, Blake completed a series of 12 mega works, including Newton at the bottom of the sea and the savage crawling king of ancient Babylon. This series is a further innovation of Blake, who does not paint directly on paper, but first draws design patterns on cardboard, then presses a piece of paper before starting to color, using watercolor and ink to complete the work. This blending technique, which makes the texture of the painting surface richer, cannot be achieved by other means.

From the scale of the Tate Black exhibition, you can see Blake's imagination space and amazing creativity. The drowning Urison, curled up on his knees as if he were about to plunge headlong into the pool; the terrifying images of the red dragon in the four apocalypse scenes—like Dr. Morrow in the horror movie with superhuman muscles, bat wings, horns on the top of his head, and scales all over his body. Glad Day is an ecstatic version of Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvius, presenting the natural state of humanity. Blake's images break through the sky and dance through the flames, curling up, jumping, marching, embracing, stretching, or waving gestures like the protagonists of a musical. For Blake, the human body presents a variety of shapes and has endless expressiveness.

Blake's Newton (1795– c. 1805) depicts a young Newton who is powerful and powerful. He had Newton sit on the bottom of the sea, intently drawing with a ruler, ignoring the colorful, seaweed-covered rocks behind him.

The comprehensiveness of this exhibit will even make visitors feel tired. One can see Blake's high degree of concentration on art, which has never faded throughout his artistic career. The exhibition also reflects the immortality of Blake's works beyond time and space while so deeply rooted in the social and artistic environment in which he lived. Even though Black seems out of place compared to more accepted artists like Turner and Constable, there are many connections between the three. Blake often walked in the Hampstead wilderness north of London, met Constebbel from time to time, and publicly expressed his admiration for the young painter. Despite their own characteristics, these three are all highly observant artists. If Turner and Constebbel succeed in interpreting the outside world, Black gazes unwaveringly into the imaginary world.

Compiled from

Michael Prodger,“William Blake’s design innovations”

New Statesman Magazine

Compiled/Zhang Wenjing