Xu Tong

"Jingkou" is the ancient name of today's Zhenjiang City in Jiangsu Province. "Jingkou Three Mountains" refers to the three mountains located in Zhenjiang: Jinshan, Jiaoshan, and Beigushan. These three mountains are three-legged and located at the intersection of the Yangtze River and the canal, which can be described as a throat land. Compared with many famous mountains, none of these three mountains are high: Jinshan is about 42 meters high, Beigu Mountain is about 52 meters high, and the highest Jiaoshan is only about 70.7 meters. However, with the rise of tourism in the Ming Dynasty, such a seemingly inconspicuous local landscape has become a desirable scenic spot and a "Immortal Mountain" that can be reached in person.

In the middle and late Ming Dynasty, whether in prints or scroll paintings, the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" image began to increase significantly and gradually formed a classic schema, which presented different cultural meanings. This article starts from some visual images in the Jingkou Three Mountains Map, focusing on its cultural meaning of The Immortal Mountain.

The popularity of "Kyoguchi Sanzan" and its prints as a scenic spot

Zhenjiang is a mountainous place, Jinshan, Jiaoshan, Beigushan these three mountains have been extracted from many mountains and called "Jingkou Three Mountains" is after historical development precipitation. As the fame of these three mountains gradually increased, they gradually became a popular attraction that people yearned for.

In the early local chronicles of Zhenjiang, there is no concept of "Three Mountains of Jingkou", and these three mountains are mixed with many local mountains such as Garlic Mountain, Yellow Crane Mountain, and Zhaoyin Mountain[2], and even the Zhenjiangshan rivers and mountains listed in the Fang Zhi of the Yuan Dynasty do not even appear in Jinshan and Beigushan [3]. The three mountains of Jinshan, Jiaoshan and Beigushan were associated and became the fixed concept of "Jingkou Three Mountains", which did not appear until the middle and late Ming Dynasty. The concept of "Three Mountains of Jingkou" was first proposed in the Ming Dynasty's Zhang Lai (HongzhiJian Juren) series, Gu Qing(弘治癸 ugly jinshi) revised the ten-volume "Jingkou Three Mountains Chronicle". The earliest surviving inscription is the Seventh Year of Zhengde (1512), which examines the famous sites and historical evolution of Jinshan, Jiaoshan and Beigushan, and collects historical poems about these three mountains. The "Jingkou SanshanZhi" not only put forward the "Jingkou Sanshan" as a fixed concept for the first time, but also according to the main theme of Fang Zhi, for the first time in the first print, the three mountains are jointly expressed in one canvas.

In 1512, the "Jingkou Sanshan Zhi" was edited to highlight the independence of the "Jingkou Sanshan", which reflected the promotion of local consciousness of the "Jingkou Sanshan" in the middle and late Ming Dynasty and towards cultural consciousness. Before the Ming Dynasty, the image of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" was rarely painted, while in the middle and late Ming Dynasty, the images of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" increased greatly and gradually formed a solid classic pattern. This is also related to the fact that the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" became a local scenic spot at this time.

Zhang Dai (1597-1679) watched the dragon boat race in the "Three Mountains of Jingkou":

The people on the golden mountain are clustered, looking across the river, and the ants are attached to the beehive, and they are eager to move. In the evening, all boats will open together, and the two sides of the strait will boil and boil [4].

This viewing took place during the Dragon Boat Festival in 1642, and Zhang Dai's perspective on the race was not on the Golden Mountain, but on the north bank of the Yangtze River in Guazhou, taking the dragon boat race, the Golden Mountain and the sea of people on the Golden Mountain as the object of viewing. In the article "Jinshan Racing", Zhang Dai believes that the dragon boat in Guazhou is the most victorious, and Jinshan wins in "watching the dragon boat", that is, in the number and momentum of the people who come to watch. Although this kind of touristy pomp and circumstance occurs in the festival, the "Jingkou Three Mountains" represented by Jinshan, as a famous place, does attract literati and the public from all walks of life. These three mountains are only a few tens of meters high, but this does not prevent them from becoming famous places in people's minds. As Young er explained in the previous examples of the "Wonders of the Sea":

"The mountain is not high, and the mountain is not strange. The water is not deep, and the water is not different. Those who are unfamiliar with the ear, who are not accustomed to it, and whose names are not urgently praised, will eventually be a desolate mountain in the silent land, and there is no one to appreciate it. Don't dare to mix it up with your own will. ”[5]

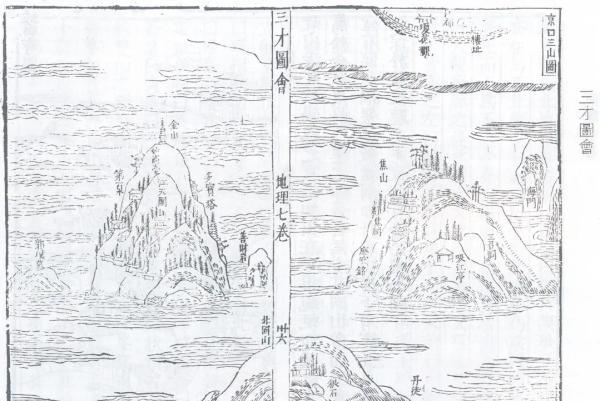

With the improvement of tourism in the Ming Dynasty and the dissemination of related publications, the fame of "Jingkou Three Mountains" was widely disseminated together with its visual image. After the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" was proposed as a fixed concept in 1512, and nearly a century later, Wang Ji (1529-1612), Wang Siyi's father and son compiled and published a print in the "Three Talents Drawing Society" in the thirty-seventh year of the Wanli Calendar (1609), including a print "Jingkou Three Mountains Map" (Figure 1). The Spectacle of Hai Nei (preface written in 1609), published around the same year or a little later, also includes the Three Mountains of Jingkou (Figure 2). The two patterns are very similar, and almost the only difference is the number of small boats floating on the Yangtze River.

Figure 1 《三才圖会・京口三山圖》

Figure 2 :Wonders of the Sea: Three Mountains of Jingkou

The "Three Mountains of Jingkou" in these two books is further integrated on the basis of previous local history prints, and the details such as the cultural landscape marked by text are retained. Compared with the actual scene, the prints in the book take into account the limitations of the layout, and the distance between the three mountains is compressed and narrowed, but as a whole, it is still centered on The North Gushan Mountain, with Jinshan mountain in its northwest and Jiaoshan Mountain in its northeast.

The publication of "Wonders of the Sea" and "Three Talents Picture Society" has a wide dissemination and influence. Published in 1609, the spectacle of Hai Nei, compiled by the bookseller Yang Erzeng (about the first half of the 17th century), was published in 1609, with print illustrations and text as a supplement, bringing together the most famous places of interest of the time, and its publication coincided with the booming trend of tourism and travel in the Ming Dynasty. "Wonders of the Sea" attracted the attention of everyone with the popular theme of "travel" of the times, coupled with sophisticated print illustrations, as the first illustrated and rich travel book, equivalent to the travel guide at that time, it was very popular after publication, and it was a very influential book at that time. The "Three Talents Picture Society" is an encyclopedic book of the Ming Dynasty, which gained a lot of recognition and influence at that time and in the future. With the publication and dissemination of these two prints in the middle and late Ming Dynasty, it should be a more popular and familiar visual image for the literati and the public who liked to travel through the landscape at that time.

By the late Ming Dynasty, the prints of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" had changed, but they continued to be published and disseminated. The Compendium of Famous Mountains and Scenic Spots in the World was engraved by Ink Painting Zhai in the sixth year of Chongzhen (1633), which also has a certain influence and dissemination, and is a popular place of interest books in the late Ming Dynasty after "Wonders of the Sea". There is also a jingkou sanshan print in this book, in which the text signs are removed and the lines are more sparse and soft. In terms of composition, Beigushan moves from the center of the lower end of the picture to the right to the corner.

In this way, Jinshan occupies one section alone, while Beigushan and Jiaoshan, together with the north bank of the Yangtze River, are arranged in another section, which highlights the importance of Jinshan. In the Ming Dynasty, Jinshan was more famous than Jiaoshan and Beigushan.[7] Suiming's emphasis on Jinshan in pictorial space is consistent with the people's perception of Jinshan's scenic spots.

"Jingkou Immortal Mountain"?

As a famous scenic spot, the "Jingkou Three Mountains" attracts literati and inkers and the public, and when people face the real scene of the "Jingkou Three Mountains" and its images, they often trigger various associations, such as the transmission of parting emotions, the feeling of the division of the north and south of the homeland in history, or the image of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" associated with the image of the distant Xianshan Mountain. This also makes a large number of Jingkou Sanshan images in the middle and late Ming Dynasty have different cultural meanings, and this article only talks about its cultural meaning of Xianshan Mountain.

Tu Long (1543-1605) once felt the magic of the combination of heaven and earth and the universe when he climbed the Three Mountains of Jingkou, and realized that the Three Mountains of Jingkou were like the Three Immortal Mountains on the Sea: "The Three Mountains of Yingzhou, the abbot of Penglai, as transmitted by dongfang Shuo's "Divine Anomaly Classic", are in the sea... The so-called Northern Gujin Jiao Three Mountains are in Runzhou Lingqi And the Three Mountains of Shuji Sea..." [8] In the Ming Dynasty poems on the "Three Mountains of Jingkou", there are often comparisons with the Immortal Mountains. For example, Qiao Yu (1457-1524) described Jinshan in "Travels to Jinshan": "The pavilion is ethereal like Penglai on the sea, and there is a non-worldly realm." [9] In the illustrated "Wonders of The Sea", in the text introduction before the Jingkou Sanshan Map, it is stated: "As if the so-called Three Sacred Mountains can be hoped for..." [10] And said that Jinshan "the mountain is negative and beautiful, and from jingkou it is regarded as the abbot of Penglai standing in weak water." [11] This allows the reader to see the visual image of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" and to associate with the image of the Sea Immortal Mountain.

Figure 3 (Biography) Li Tang's "Floating Jade on the Great River" is collected by the National Palace Museum in Taipei

The main body of the album "Floating Jade of the Great River" (Figure 3) is the Golden Mountain, as if it is floating in the middle of the water. The painting was previously signed as the work of Li Tang (1066-1150) according to the old inscription, and Jiang Zhaoshen believed that it may be the work of Li Guo's school between the Northern Song Dynasty Xuan and Shaoxing. Whether from the title of the painting or the image in the painting, the album of "Dajiang Floating Jade" is in line with the characteristics of Jinshan. The landscape to the south of Jinshan is depicted, surrounded by hills on both sides: Shipai Mountain to the west and Hushan Mountain to the east. In addition, the two pagodas on the mountain are also in line with the characteristics of the Golden Mountains in the Northern Song Dynasty. Zhou Bida (1126-1204) said that Jinshan "surrounds the great river, and every wind and waves are everywhere, and it is eager to fly, so the Southern Dynasty is called the Floating Jade Mountain." [13] Jinshan has many ancient names, and "floating jade" is one of them. Since ancient times, there has been more than one place called "Floating Jade". For example, the Floating Jade Mountain in the Classic of Mountains and Seas: "Looking north at the Gu District, looking east at zhubi, the water comes out of its yin, and the north flow flows into the Gu District." Later generations believed that it referred to the branch of Tianmu Mountain in Zhejiang Province[14]. Qian Xuan's "Floating Jade Mountain Residence Map" shows the Floating Jade Mountain in Huzhou. Jinshan and Jiaoshan in the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" also have the name of "floating jade". The names of these floating jades actually come from the Daozang: "Daozang Jingshan was originally named Floating Jade, and it floated from the peaks of Yujing. [15] "Yujing Mountain" is a mountain of great importance in Taoism, and above it is the highest heaven of Taoism, Luo Tian. The legendary Floating Jade Mountain is separated from the peaks of Yujing. Including Jinshan and Jiaoshan, these floating jade mountains in the world are more than the Immortal Mountain system attached to Taoism.

Figure 4 (Biography) Wen Zhengming's "Golden Mountain Map" Axis Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei

Among the images of the Three Mountains of Jingkou that appeared in large numbers in the middle and late Ming Dynasty and went to self-realization, there is a (chuan) Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) "Golden Mountain Map" (Figure 4), which places the image of Jinshan in the form of a vertical axis in the lower middle of the picture, surrounded by rivers and waters. At the top of this figure is a seven-word poem by Guo Xiangzheng (1035-1113) of the Northern Song Dynasty:

The golden mountain is in the vicissitudes, and the snow cliff icicle floating immortal palace.

Qiankun has been supported since ancient times, and the sun and moon seem to be entangled in the west and the east.

I came out of the earthly world and searched for otherworldly voyeurisms.

Once he ascended to the throne, he sighed heavily, and imagined how majestic he was at four o'clock.

The roller blind night pavilion hangs the Big Dipper, and the big whale rides the waves to blow in the sky.

Boats destroy the shore and break the number of feet, often thunderbolts pound the dragon.

The cold toad swings the Yao Sea in August, and the autumn light grinds bronze up and down.

Birds fly endlessly in the twilight sky, and fishing songs suddenly break the reed wind.

Penglai has not been heard for a long time, and the grandeur is the same.

The tide is still dawning at night, and things and numbers will be able to be poor!

A hundred years of shadow waves suffering from themselves, they wanted to settle down here.

Bai Yunnan came and went into the distance, and then returned to Xingxing with Zhenghong.

After the poem, it is also inscribed with the inscription "Jiajing Nong Noon Autumn Zhongxi Twenty-two, Dengjin Mountain Crossing Jinling Boat In the Middle Of the Ink Works, Zhengming." The poem uses phrases describing the fairyland, such as the Immortal Palace, the Earthly World, the Otherworld, the Divine Worker, the Yaohai, and the Penglai Mountains, which, together with the images of the Golden Mountains, combine an accessible real scene with the Immortal Mountains of the Birth. In this painting, the image of the golden mountain in the middle of the water matches the poem copied above, highlighting the attributes of the immortal mountain in this place.

Of course, this work is a certain distance from Wen Zhengming's authentic handwriting, both in terms of pen and ink technique and calligraphy, but this work is still meaningful to discuss.[16] Even if this "Golden Mountain Map" axis is a forgery, this map is not only not without value for the Qianlong Emperor (1711-1799), but also very important, it still influenced the Qianlong Emperor, and even opened the Qianlong Emperor's imagination of Jiangnan. This picture is recorded in the "Shiqu Baodi Preliminary Compilation and Imperial Study". On this axis there is a royal inscription poem of the Qianlong Emperor:

Not to The Jiangtian Temple, An Zhikong Kuoqi.

Carry the personal evidence, the situation is as solid as it is.

Xin Weinan toured, carrying this frame in the middle of the line.

In February, I looked forward to sitting in jinshan jiangge because of the inscription royal pen.

It can be seen from the inscription that the Qianlong Emperor's imperial inscription was made in February of Xin Weinian (1751) (February 16), coinciding with the first southern tour. The Qianlong Emperor set out from the Beijing Division on the thirteenth day of the first month of 1751[17], and after more than a month, on the Jinshan River Heavenly Pavilion, while viewing the scenery of the Jingkou area, he took out the "Golden Mountain Map" axis he carried with him and compared it, feeling that the actual landscape of the place was just as the painting shown. The Qianlong Emperor left a number of inscriptions on his first southern tour to Jinshan, and once sighed in the poem "The First Ascent of Jinshan": "Wangu Hao Yin who creates the pole, for a time wins the Ruo Dengxian." When the Qianlong Emperor who first ascended the Golden Mountain saw the Golden Mountain, he thought of the two immortal mountains of Fangju and Yuanjiao, and this connection was just as he saw (chuan) the connection between the images in the axis of Wen Zhengming's "Golden Mountain Map" and the Song poems on it.

The Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722) also described Jinshan in the poem "Two Hopes of Jinshan" as "not letting Pengying Island go up the mountain"[19], that is, compared with Penglai and Yingzhou in the legendary Three Gods mountains on the sea in the history of Han culture. The Second Emperor of Kangqian sighed like a fairy mountain in Jinshan, but they all clearly sighed that this was the most beautiful QingJiangshan. The process of the Second Emperor's southern tour is the process of communicating between the north and south of the great river, and it is also a symbol of the unification of the Han nationality. And the golden mountain that they climbed many times, chanted and ordered to draw was located on the node of this jiangnan and jiangbei. Jinshan and even the three mountains of Jingkou are all famous scenic spots that can be owned by the Qing emperors, but they are like the Immortal Mountains that the emperors of the Warring States and the Qin and Han Dynasties have wanted to pursue but can never reach, which is also the ideal landscape under the Qing Empire.

Visual association with The Immortal Mountain

From the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" to the Sea Immortal Mountain, it did not begin in the Ming Dynasty, and there was often such an association in the dynasties and dynasties. For example, during the Southern Dynasty, the area around the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" triggered people's associations with the Immortal Mountains:

Xun Zhonglang was at Jingkou, climbing the Gushan Mountain in the north and looking at the sea and clouds: "Although he did not see the three mountains, he made people have the intention of lingyun." If the king of Qin and Han is a king, he will be clothed with his feet. [20]

Because the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" is connected by rivers and seas, the clouds are swirling, and there are three lonely mountains sitting in the middle of the rivers and seas, which looks like a fairy mountain in Xunzhong Lang Xun Xian (322-359), and believes that the kings of the Qin and Han dynasties, if they arrived here, would definitely lift their clothes and wet their feet to seek immortals. Since the pre-Qin era, China has always had the search and imagination of the Immortal Mountains. The Book of History and Feng Zen records:

Ziwei and Xuanyanzhao sent people into the sea to seek Penglai, abbot, and Yingzhou. This three sacred mountain people. Its transmission is in the Bohai Sea, and it is not far from people, and when it is troubled, the ship wind will lead it away. The one who tastes it, the immortals and the elixir of immortality are all in the making. Its objects and beasts are white, and the gold and silver are palaces, and they are not as far as the clouds, and when they reach the Three Gods Mountain, they live under the water, and the wind is leading away, and they will not be able to reach it in the end. [21]

Sima Qian records that since the Warring States Period, King Qi Wei, King Qi Xuan, and King Yan Zhao, they have continuously sent people to the sea to seek the legendary three sea sacred mountains: Penglai, Abbot, and Yingzhou. "The First Emperor thought he was at sea, but he was afraid that he would not be able to do so. Men and women who make men and women go into the sea to seek it, and when the ship is delivered to the sea, they all take the wind as the solution, and they have not arrived. [22] From the beginning of the pre-Qin era, to the later Qin Shi Huang and Emperor Wu of Han, they repeatedly sent people to search for the Sea Immortal Mountain, but they were always "unable to reach it in the end". This immortal mountain that never reached was more and more mysterious and full of imagination in people's minds. The image of the Three Mountains of Jingkou always has many similar visual elements to the image of The Immortal Mountain that people imagine.

(1) Mt. Mikami

The "Three Mountains of Jingkou" is located at the intersection of the Yangtze River and the canal, and the water surface is open and empty. In such an environment, the three mountains relationship of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" often triggers people's reverie of the Three Sacred Mountains on the sea.

Scholar Wu Hong believes that the three peaks of the Chinese character "mountain" provided the ancients with the basic framework for visualizing the Immortal Mountain. In early art, such as the lacquer coffin excavated from Tomb No. 1 of Mawangdui and the upper part of the painting excavated from Jinque Mountain in Shandong, there are images of three peaks, which Wu Hong believes refers to another system of Immortal Mountains in addition to the Sea Immortal Mountain System: Kunlun. This vision of the three peaks representing the image of the Immortal Mountain has always continued, and has increasingly become a symbol, and this symbolic image of the Immortal Mountain can be recognized and recognized in the visual experience of the ancients. Isles of the Blessed, now in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, is inscribed by Pu Guang, a yuan dynasty painter who was a scholar of Shōbunkan University (active in the late 13th and early 14th centuries). In the capuchin part, there are three steep peaks independent of the big waves, and these three mountains are known at a glance as typical images of immortal mountains. In such a mountain, its character activities and pavilion architecture must not be mortal, plus there are immortals driving cranes or clouds in the air. This image of the Three Peaks is associated with the meaning of the Immortal Mountain, which is common in the visual experience of the middle and late Ming Dynasty. For example, in the famous ink spectrum "Cheng's Ink Garden" during the Ming Dynasty, there is the image of "Three Sacred Mountains", that is, three isolated islands standing in the water (Figure 5). This has much in common with the image of the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" in the prints. The divinity of the Three Mountains also exists as a decorative or suggestive visual symbol. For example, yuanren's painting of the axis of the "Reed Crossing Diagram" (Fig. 6) shows the scene of Dharma crossing the river by reed leaves. In the painting, there are three mountain stones standing at the feet of Dharma in the rough waters of the river, these three stones add a mysterious atmosphere to the picture, as a recognizable visual symbol to convey a non-worldly sanctity.

Figure 5 "Cheng's Ink Garden, Three Gods Mountain"

Figure 6 Yuanren 'Reed Crossing Map' Axis Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei

(2) Lonely Mountain, Lonely Root

As mentioned above, the historical "floating jade" alias of Jin and Jiao Ershan comes from the Daozang, which is an immortal mountain floating from the Yujing Mountain, which has a very high status in Taoism. However, the name "Golden Mountain" also comes from the extraordinary sacred realm system in Buddhism. Mount Meru is a sacred mountain in Buddhism located in the center of a small world, which is also transliterated as Myoko Mountain (there is Myokodai on Jinshan Injin, Zhenjiang). In Buddhism, it is believed that Mount Meru is surrounded by seven mountains and seven seas, and the seven mountains that surround it are called The Golden Mountain. The small lonely peaks of the bronze Mount Meru, located in the lower part of the Lama Temple in Beijing today, are the symbols of the Golden Mountain, which envelop and support the tall Mount Meru in the center. Whether it is Mount Meru or the surrounding small golden mountains, the image of the peak is the appearance of a lonely mountain in the sea.

The shape of the Boshan furnace is considered by many modern scholars to be an imitation of Xianshan Mountain. The Mancheng Han Tomb unearthed the wrong gold and silver Boshan furnace, as if a steep lonely mountain in the sea, and golden flowing clouds and sea gas patterns decorated on the hearth under the "Lonely Mountain". When lit by the smoke from the smoker, the atmosphere that spreads out is like a sea fairy mountain (Picture 7). In the Axis of Wei Jiuding's "Luoshen Diagram" (Figure VIII) of the Yuan Dynasty, on the fan in Luoshen's hand, there is an image of a lonely mountain on the sea, and this symbol is also obviously a fairy mountain. Through this, it also conveys the divinity of Roselle. In the Ming Dynasty, such images of the Immortal Mountains were still inherited.

Figure 7 Mancheng Han Tomb unearthed a wrong gold and silver Boshan furnace Hebei Museum

Figure 8 Wei Jiuding "Roselle Diagram" Axis Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei

In the "Three Mountains of Jingkou", Jinshan and Jiaoshan are isolated islands located in the heart of the river, and this vision often reminds people of the characteristics of Xianshan. In addition, the lower parts of sacred mountains such as Mount Meru and Mount Kunlun often have an image of a "lone root", which is just as Dongfang Shuo described Kunlun Mountain in the "Ten Continents": "The shape is like a basin, narrow at the bottom and wide on the top." [25] This image of a large, large, small, bottom with fine roots connected downwards is one of the characteristics of the traditional Chinese image of Xianshan. In a late Eastern Han Dynasty stone carving unearthed in Shandong, the Queen Mother of the West sits firmly on the broad and flat Kunlun Mountain at the top, and the roots of this Kunlun Mountain are lonely and curved. In the mural painting of Yongle Palace in the Yuan Dynasty, a fan held by an immortal is also painted with a mountain-shaped pattern of "lower narrow and upper wide", and the top of the temple on the mountain is radiant. In the "Lingbao Jade Jian" in the "Daozang", there is almost the same pattern, and the Wuming fan is painted with a mountain with a narrow upper and wide range, and there are also temples and ten thousand rays of light above. In the Ming Wanli Ink Spectrum "Cheng's Ink Garden", the visual image of the Pure Land of the Buddha's Kingdom in Buddhism, the "Suntan Sea" (Fig. 9), also adopts the shape of a mountain with a lower narrow and wide mountain, and there is a shrine on the top of the mountain, but this mountain is located in a lotus flower. It can be seen that this fusion of the image of the Immortal Mountain in the Sacred Realm of Buddhism and the popularity of this image in the visual experience of the literati of the Ming Dynasty.

Figure 9 "Cheng's Ink Garden, Tan Tan Hai"

Jinshan in Zhenjiang is a real landscape that can be visited, and in the description of the literati, it also has the characteristics of a lone root that only exists in the Immortal Mountains. Wang Anshi (1021-1086) once described Jinshan as "a lonely root and a vast underworld, except for the dragon world." [26] The Ming Dynasty scholar Wang Siren (1574-1646) also said in the "Journey to the Golden Mountains" that "reading the Records of the Three Mountains, there used to be different monks, the roots of the golden mountains, and the bottom could not be bottomed, and the cloud stems became more and more lonely, like fungi leaning on." That is to say, in the legend about the "Three Mountains of Jingkou", there was a monk who went to dig the roots of the Golden Mountain, digging deeper and deeper, and found that its roots were getting thinner and thinner, like mushrooms. The Queen Mother of the West in the Eastern Han Dynasty portrait stone carving unearthed in Shandong is sitting on such a mushroom-shaped immortal mountain.

(3) Smoke clouds and sea gas

Historically, the estuary of the Yangtze River was once in the Jingkou area, and the mouth of the ancient Yangtze River was trumpet-shaped, and since the Qin and Han Dynasties, the river surface has gradually shrunk, and the estuary has slowly moved eastward. In the aforementioned "Wonders of the Sea", the seal "Three Mountains of Jingkou" shows that the Haimen Mountain on the east side of Jiaoshan Mountain is a symbol of the place where it enters the sea. The section of "Haimen Mountain" in Ma Yuan's "Twenty Views of Painting Water" (now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei) should also depict here. The Southern Song Dynasty scholar Lou Key (1137-1213), who was probably the same period as Ma Yuan, once had a sentence in the poem "Eight Scenic Pictures of Dong Heng Dao": "Many scenes are majestic according to Jin Jiao, and the sunset is slightly illuminating Haimen Mountain." [27] That is to say, one of the eight scenes painted by Dong Hengdao is the scenery of Jinjiao Ershan Mountain and the Haimen Mountain on the east side of Jiaoshan Mountain. During the Wei and Jin Dynasties, Tang Dynasty, and Song Dynasty, it was still possible to look out over the sea. For example, in Tang poems, the Jingkou generation often depicts verses such as "opening feasts to meet the tide of the sea"[28], "Yishan near the seashore"[29] (Yishan is one of the two Haimen Mountains), and "Baibo sinking but Haimen Mountain"[30]. Although the Zhenyang River section (the Yangtze River between Yangzhou and Zhenjiang) began in the 8th century,[31] the junction of rivers and seas during the Five Dynasties and the Song Dynasty still existed. For example, Xu Xuan (916-991) said in "Looking North of Dengganlu Temple": "The wind and waves at Haimen are peanuts." ”[32]

It is also because the psychedelic sea air here often constitutes the atmosphere of people's association with the Immortal Mountain, just like the aforementioned Northern Song Dynasty Guo Xiangzheng Seven Words Poem. During the Song Dynasty, the area around Jingkou was "noisy and noisy"[33], and as time went on, the sediment accumulation of the Yangtze River estuary gradually moved eastward. In the Ming Dynasty, the area around Jingkou gradually lost its turbulent momentum. As Guo Diyun, who collected Shen Zhou's "Jinjiao Ershan Map": "Poor Yangzi crossing, I don't see the sea tide." [34] But even so, the sea-filled nature here still exists and does not affect people's reverie about the Immortal Mountain.

The sea air in the Jingkou area is full of air, three peaks stand on three feet in the river, and the two isolated islands in the water of Jinjiao Ershan look at each other in the distance. The temples on the Golden Mountain are dense and splendid, and there are XiayuanShuifu under the Golden Mountain and there are many fish and dragons, which were located in the past at the mouth of the sea and were difficult to reach... These characteristics have too many similarities with the image that people have imagined for a long time. Literati and inkers described it as "a small pengying out of the heart"[35], "why look at Yingzhou"[36]... The visual experience similar to that of Xianshan has greatly increased the reputation of the "Jingkou Sanshan" and attracted more people to feel the "immortal qi".

Today, however, Jinshan is a park in the center of Zhenjiang. Tourists rub shoulders and heels, and it is difficult to feel the "fairy spirit" of that year. The loss of this "immortal qi" began at the end of the Qing Dynasty. The image of Jinshan in the "Jingkou Three Mountains Chronicle" between Tongzhi Guangxu has changed, the golden mountain has been ashore in the print, the surrounding weeds are overgrown, no longer the mysterious isolated island located in the heart of the river, there is no big wind and waves that make it difficult to get close by boat, the Yangtze River has long been diverted, and the estuary has long been moved east, at this time people can already "ride a donkey to the golden mountain". Did the people who felt that the "Three Mountains of Jingkou" resembled immortal mountains ever thought about these vicissitudes behind them?

exegesis:

[1] The data comes from the zhenjiang city history office http://szb.zhenjiang.gov.cn/.

[2] (Song) Shi MiJianxiu, (Song) Lu Xian, Jiading Zhenjiang Zhi, vol. VI, Shan Chuan, according to Song Jiading 6 (1213) Xiu, Qing Daoguang 22 (1842) Dantu Baoshi engraving photocopy, Song Yuan Fang Zhi Series, vol. 3, Zhonghua Bookstore, 1990, pp. 2353-2363.

[3] (Yuan) Yu Xilu, ed., Zhishun Zhenjiang Zhi, vol. VII, Shanshui, Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House, 1999, pp. 269-270.

[4] "Jinshan Jingdu", (Ming) Zhang Dai: "Tao'an Dream Memories West Lake Dream Search", Zhonghua Bookstore, 2007, p. 67.

[5] (Ming) Yang Erzeng: Wonders of The Sea, Zhejiang People's Fine Arts Publishing House, 2015, p. 28.

[6] These two lithographic illustrations also have an earlier source of schemas, namely Wang Shisheng (1547-1598): Printmaking Illustrations in the Five Mountains Of Grass.

[7] Yuan Yuan of the Ming Dynasty explained one of the reasons why Jinshan was so well-known: "Jinshan should be the throat of Runzhou, and those who cross the river will travel well." Jiaoshan Mountain is secluded, so tourists are particularly fresh. See Yuan Yuan: "The Tale of the Two Mountains of Jinjiao", quoted from (Qing) Chen Menglei et al., compiled the "Integration of Ancient and Modern Books", Fang Yu Compilation of Mountains and Rivers, vol. 191, photocopied by Zhonghua Bookstore, 1940, p. 50.

[8] (Ming) Tu Long: "The Chronicle of the Three Mountains", (Qing) Chen Menglei et al., compiled "Ancient and Modern Book Integration", Fang Yu Compilation of Shan Chuan Classic, Photocopy by Zhonghua Bookstore, 1940, vol. 191, p. 34.

[9] (Qing) Chen Menglei et al., compiling "Ancient and Modern Book Integration", Fang Yu Compilation of Mountains and Rivers Classics, photocopied by Zhonghua Bookstore, 1940, vol. 191, p. 38.

[10] With [5], p. 193.

[11] Same[5], p. 196.

[12] Jiang Zhaoshen, ed., Essence of Song Painting, vol. 1, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1976, p. 13.

[13] Zhou Bida: Erlaotang Magazine, quoted from (Song) Shi MiJianxiu and (Song) Lu Xianlu, Jiading Zhenjiang Zhi, Song Yuan Fang Zhi Series, vol. 3, Zhonghua Bookstore, 1990, p. 2358.

[14] Etymology, The Commercial Press, 1998, p. 974.

[15] (Song) Shi Mijianxiu and (Song) Lu Xianxiu, Jiading Zhenjiang Zhi, Song Yuan Fang Zhi Series, vol. 3, Zhonghua Bookstore, 1990, p. 1357.

[16] Wen Zhengming painted The Golden Mountain. His "Golden Jiao Falling Photograph" (Shanghai Museum collection) shows the scene of Jinshan and Jiaoshan facing each other in the heart of the river, showing its local real-life characteristics and unique emptiness.

[17] See Yang Duo, "A Study on the Southern Tour of Qianlong", Master's Thesis of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, 2004.

[18] See The Complete Imperial Poetry of Emperor Gaozong of the Qing Dynasty, vol. II, Chinese Min University Press, 1993, p. 476.

[19] See Qing Shengzu Imperial Collection, Vol. 2, Vol. 50, Forbidden City Rare Books Series, Vol. 545, Qing Dynasty Imperial Poetry Collection, Wanshou Poems, Qing Shengzu Imperial Poetry, vol. IV, Hainan Publishing House, 2000, p. 328.

[20] (Southern Dynasty Song) by Liu Yiqing and Yu Jiaxi's annotations on "The New Language of the World", Zhonghua Bookstore, 1983, p. 135.

[21] [22] Records of History, vol. 28, Feng Zen Shu No. 6, Zhonghua Bookstore, 2012, p. 1355.

[23] [24] Wu Hong: "Fine Arts in Time and Space", Life, Reading, and New Knowledge Triptych Bookstore, 2009, p. 136.

[25] Quoted from (Northern Wei) Li Daoyuan and Chen Qiaoyi's "Water Sutra Annotation Proof", vol. 1, Zhonghua Bookstore, 2007, p. 12.

[26] (Song) Wang Anshi: "Jinshan", written by Ming Xu Guochengxiu and Gao Yifu, "The Complete Chronicle of the Three Mountains of Jingkou", photocopied in the twenty-eighth year of the Ming Wanli Calendar (1600), Chengwen Publishing House Co., Ltd., p. 262.

[27] (Song) Lou Key: The Collected Works of Attacking Yuan, vol. 5, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. edited the Photocopy of wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1152, jibu vol. 91, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986, p. 338.

[28] (Tang) Zhang Zirong: "Nine Days accompanying Shao Envoy Junjun of Runzhou to ascend Beigushan Mountain", "Miscellaneous Songs of the Year", vol. 34, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, etc.: Photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1348, Volume 287, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986. p. 436.

[29] (Tang) Meng Haoran: "Yangzi Jinwang Jingkou", Yuding Quan Tang Poems, vol. 160, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. Compilation of photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1424, Volume 363, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986. p. 469.

[30] (Tang) Lu Tong: "Yang Zijin", "Yuding Quan Tang Poems", vol. 387, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. edited "Photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu" vol. 1426, volume 365, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986, p. 715.

[31] Chen Jiyu, Yun Caixing, Xu Haigen, Dong Yongfa, et al., "The Pattern of Yangtze River Estuary Development in two thousand years", Journal of Oceanography, No. 1, 1979.

[32] (Song) Xu Xuan: "Looking North of Dengganlu Temple", "Riding Province Collection", vol. 1, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. Compilation of photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1085, Jibu Vol. 24, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986, p. 5.

[33] (Song) Zhu Xi: "Climbing the Golden Mountain", Song Poetry Chronicle, vol. 48, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. Compilation of photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1485, Volume 424, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986, p. 57.

[34] (Ming) Guo Di: "Out of Yangzi Bridge to See the Colors of Jiangnan Mountains", Yuxuan Ming Poems, vol. 60, (Qing) Yong Yao, Ji Yun, et al. Compilation of Photocopy Wenyuange Siku Quanshu, vol. 1443, Volume 382, Taiwan Commercial Press, 1986, p. 516.

[35] Shao Xi's poems, see Ming Xu Guocheng Xiu and Gao Yifu: "The Complete Chronicle of the Three Mountains of Jingkou", photocopied in the 28th year of the Ming Dynasty (1600), Chengwen Publishing House Co., Ltd., 1983, p. 327.

[36] Jia Cheng's poems, see Ming Xu Guocheng Xiu and Gao Yifu: "The Complete Chronicle of the Three Mountains of Jingkou", photocopied in the 28th year of the Ming Wanli Calendar (1600), Chengwen Publishing House Co., Ltd., 1983, p. 332.

Editor-in-Charge: Han Shaohua