In paris, the cathedral where Victor Hugo gave her meaning beyond the religious dimension, making her the most popular symbol. Since the Middle Ages, she has experienced all the turmoil in the history of the capital, witnessing her splendor and decline.

Whether or not you know french history, it is a symbolic moment of horror, a historic event, a nightmare horror for anyone who loves her. It is the heart of a nation that burns before the eyes of hundreds of millions of human beings, some of whom have strolled through her temples as tourists, weaving through ancient stone pillars and altars containing countless mysteries, marveling at the solemn atmosphere that permeates the air, by the towering vaults and the magnificent rose windows. Did Paris burn? Metaphorically, yes. Surrounded by thick smoke, this merciless fire is like a painful drama, which is difficult to stop once staged.

The burning roof trusses support not only sacred domes and proud arrows, but also an important part of French identity, which is filled with memories from school textbooks and myths and legends, Charles VII and Joan of Arc, Henry IV and Bosshuy, from the Revolution to the two Bonapartes, the Liberation of Paris, Claudel, Marshal Pétain, General de Gaulle, especially in popular culture, as well as Quasimodo, Frollo and Esmeralda, the protagonists of Hugo novels, paper cultural monuments that multiply the glory of stone monuments.

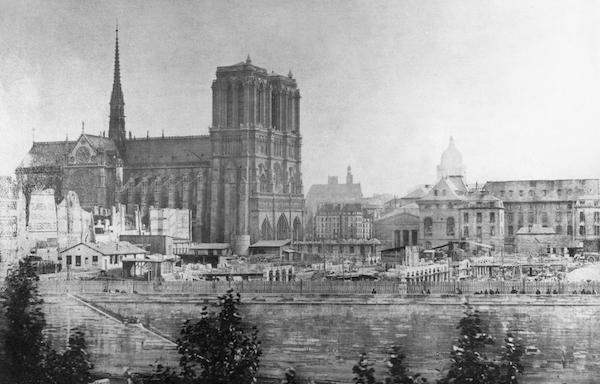

In 1878, the Main Palace Hospital and Notre Dame Cathedral were under restoration. Image source: French National Archives

As the great Hugo wrote, Notre Dame originally meant the brutal Middle Ages. She was unjustly despised, and historians justified her name, which gradually became admired by the public, and even set off a strong religious fanaticism. The bloody plot behind her is comparable to Game of Thrones, and the suffering and killing make people disbelieve in the kingdom of heaven. The giant stone ship, which is stationed in the heart of the capital's civilian district, became a household name. On this island within the city, where the ancient town of Lutetia was founded, the mighty Church built this stone sacrifice for the God who ruled over Europe. Sitting west and facing east, like many cathedrals, looking at Jerusalem, the thick twin towers, the nave lined with huge columns, the ear hall illuminated by rose windows, the altar that stretches out like a bow to the Seine, and the soaring spire overlooks Christian Paris, becoming the embodiment of the supreme power of Catholicism. Around her were crumbling shacks and poor people accustomed to being associated with misfortune, struggling to pray for shelter from the mysterious power of the crown of Jesus and other holy relics brought back by Saint Louis. Inside the stone walls of the cathedral, there are all kinds of people, from believers, rich people, noble lords, to the fallen wicked, the expelled, and the poor. It is often thought that the walls are lead-gray, but in fact, the frescoes that once shone with gold have been worn away by time, and the subsequent era believes that religion should be so serious and simple, it has never been repaired and restored.

Wedding of Henry de Nawal (future Henry IV) and Margaret de Valois (Queen Margot) in August 1572, a work of 19th-century printmaking. (Tallandier. BRIDGEMAN)Le mariage de Henri de Navarre, futur Henri IV, et de Marguerite de Valois, la «reine Margot», en août 1572, sur une gravure du XIXe siècle. (Tallandier. BRIDGEMAN)

In this living museum, major events follow closely together, marking moments in the history textbooks of the Republic. During the war with the Pope, the American man Philip (Philip IV) convened the first national tertiary council here; during the Hundred Years' War, charles VI, the young king of France and England, was crowned here, just like the later Mary Stuart (Mary I). After retaking the occupied kingdom, Charles VII celebrated the return of his capital from the British and burgundians, singing Te Deum for the first time here, and singing triumphant songs all the way thereafter. He also called a church trial to avenge Joan of Arc, who had been burned at the stake in Rouen. Queen Margot married Henry of Navarre, where the Huguenot congregation remained until six days later, when the marriage, which sought reconciliation, turned into a bloody honeymoon of st. Bartholomew's massacre. This was followed by a chant of praise for the wedding of Louis XIV, and a solemn speech by Bossuet for the death of the Prince of Grand Condé.

It was in this same place that Napoleon was crowned, taking a crown from the Pope and putting it on his head, and then putting a crown on Josephine, a scene that was forever recorded by David's brush. His nephew Napoleon III married the Empress here and later baptized the Crown Prince. During this period, the history of the Revolution had ephemerally transformed the cathedral into a "temple of reason," turned the church into a granary, melted bells to cast cannons, and attempts to abandon the Christian faith were ultimately in vain.

Photographs of victory celebrations published in Excelsior on November 17, 1918. Image credit: Roger-Viollet Pictures

The darkest hour of the occupation: Marshal Pétain was solemnly received by Cardinal Suhart amid the cheers of the Parisians in April 1944. The bright hour came, the liberation of Paris began in the square in front of the church, and on August 24, 1944, Captain Drona's armored vehicle, surrounded by a group of Spanish Republicans, occupied the headquarters of the police station, followed by the town hall a few steps away, and the final climax of the uprising was that General de Gaulle, together with the leaders of the "Free France" and the resistance, came to the cathedral and sang "Praise" and "Marseille" with the accompaniment of the organ. According to records, at the moment they entered the church, there were snipers on the roof ambushing the crowd below, while General de Gaulle remained upright and walked slowly into the main hall.

Still at Notre Dame Cathedral, Claudel said she found her faith behind a pillar where state funerals were held for Charles de Gaulle, Pompidou and Mitterrand, although Mitterrand himself preferred Saint-Denis' Cathedral and its sleeping figures of the dead. The funerals of Father Pierre and Sister Emmanuel were also held here. Far-right writer Dominique Wenner committed suicide here, and people gathered here after the November 2015 attacks in Paris.

Therefore, Notre Dame is the most important and traditional thing for our history. The same is true for our people. Hugo depicts the gloomy mood of faith, but he writes more about how the abundance of popular sentiments enlivens the church square and even the nave, where craftsmen, pickpockets, porters, and prostitutes rub shoulders, where the Roma maiden Esmeralda dances, where Quasimodo endures torture, and where he lives in the dark clock tower that has just been burning. Before him, Eugène Sue began the original story of her Secrets of Paris on the island in the city, when it was still the poorest neighborhood in Paris, and this documentary novel depicted for the first time the unfortunate lives of these forgotten people, depicting their humanity and dignity. Finally, there is a popular musical that brings the glory of this building to the world with a catchy melody, and with it a great legendary history, as well as the humanistic struggle of a people who are both pious and rebellious.

(This article was published on the evening of April 15, Paris time, and the author is the current editor-in-chief of the French newspaper "Liberation".) The compilation of the text is reproduced from the French "Liberation Newspaper", compiled by Du Su. )