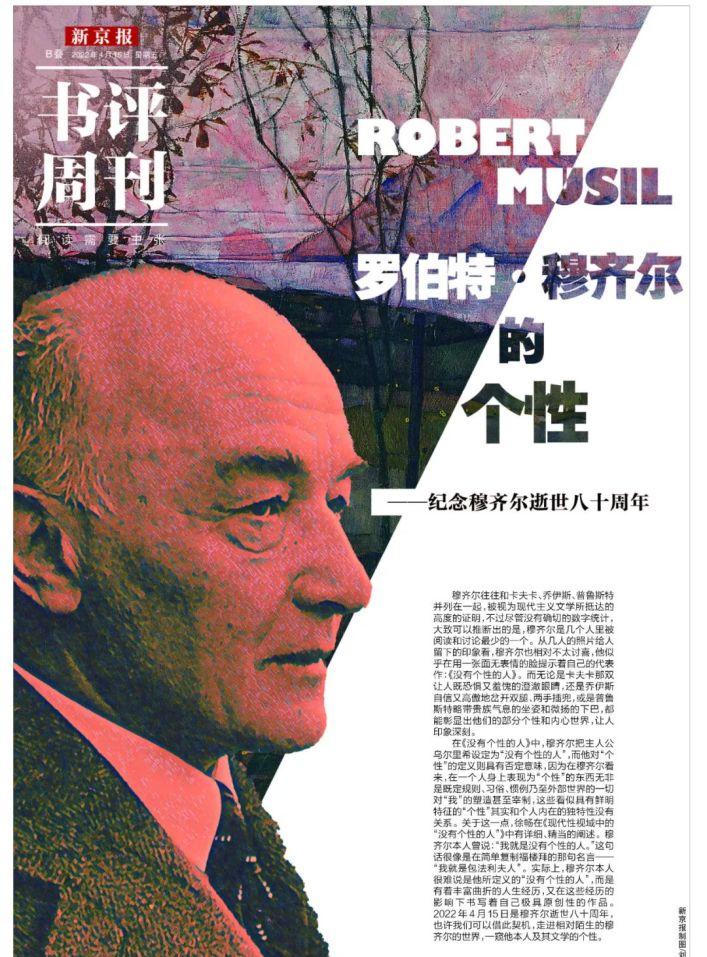

Muzier is often juxtaposed with Kafka, Joyce, and Proust as proof of the height reached by modernist literature, but although there is no exact numerical statistic, it can be roughly inferred that Muzier is the least read and discussed among several people. From the impression left by the photos of several people, Muzier is also relatively unpleasant, and he seems to be using an expressionless face to suggest his masterpiece: "The Man Without Personality". Whether it is Kafka's clear eyes that are both frightening and ashamed, or Joyce's confident and proud legs and pockets, or Proust's slightly aristocratic sitting posture and slightly raised chin, they can show part of their personality and inner world, which is impressive.

In "The Man Without Personality", Muzir sets the protagonist Ulrich as a "person without personality", and his definition of "personality" has a negative meaning, because in Muzier's view, what is expressed as "personality" in a person is nothing more than the shaping and even domination of "I" by established rules, customs, conventions and even all the external worlds.

On this point, Xu Chang has a detailed and well-described exposition in "The "Man Without Personality" in the Perspective of Modernity". Muzil himself once said, "I am a man without personality." This sentence is very much like a simple copy of Flaubert's famous quote - "I am Madame Bovary".

In fact, Muzier himself can hardly be said to be a "person without personality" as he defines it, but he has a rich and tortuous life experience, and under the influence of these experiences, he writes his own extremely original works.

April 15, 2022 marks the eightieth anniversary of Muzier's death, and perhaps we can take this opportunity to step into the relatively unfamiliar world of Muzier and get a glimpse of himself and his literary personality. (Introduction: Zhang Jin)

This article is from B02-B03 of the Beijing News Book Review Weekly's April 15 feature "Robert Muzier's Personality: Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of Muzier's Death".

"Theme" B01丨 Robert Muzier's Personality – Commemorating the Eightieth Anniversary of Muzier's Death

"Theme" B02-B03 丨 Ends with a comma: Muzier's life, personality and writing

"Theme" B04-B05丨How to settle the homeless soul of modern people?

"Theme" B06 丨 "Legacy works" in the stable life is not such a beautiful thing

"Literature" B07丨 "The Only Story" examines the obscuration of the narrative itself

"Literature" B08 丨 Mao Jian We are all the app of this era

Written by 丨 Xu Chang

Muzier, born in 1890, is an Austrian writer, one of the most important Writers of German-language literature of the twentieth century, alongside Kafka, Joyce and Proust, the most important great writers of the twentieth century. Representative works include "The Man Without Personality", "The Confusion of Student Torres", "Three Women", "Legacy works" and so on.

At noon on April 15, 1942, the Austrian writer Robert Muzier, who was exiled to Switzerland, died of a sudden cerebral hemorrhage in his temporary residence in Geneva. That morning, he was revising his manuscript at his desk, what would become known as The Man Without Personality, one of the greatest and most famous works of twentieth-century modernist literature.

Prior to this, the novel had been published in two volumes (1930/1933) with more than a thousand pages. For decades, many fans and researchers have wondered a question: If Muzier had not died young, what would have happened to "The Man Without Personality"? Of course, there is no longer any answer to this question. But Muzier said during his lifetime that he wanted to end the novel with a sentence halfway through, and that it should be a comma that ended the book.

Muzil was suddenly ill in the bathroom, and according to his widow later, the expression on his face when she found him was a "mockery and slight surprise". As an outstanding master of irony, perhaps what he thought of at the last moment before his death was precisely this irony arranged by fate: what ended first with a comma was his life.

Muzil once said, "I am a man without personality." But in fact, unlike the title of his novel's diagnosis of the mental and emotional structure of modern Europeans, Muzier himself and his writings have distinct personalities. He received a military and engineering technical education from an early age, and although he later abandoned his work and followed the literature, he always demanded his writing according to the standard of scientific "precision". At this request, he advanced the difficult thinking in the novel with almost stubborn persistence, striving to paint spiritual portraits of the various chaotic and complex ideological currents and cultural schools in Europe from the end of the 19th century to the 1930s.

Although he regards the class, professional, national and other attributes of human beings as non-authentic "other" factors in "The Man Without Personality", his own disposition and literary personality are inseparable from his growth path, educational background and life experience.

Graffiti on the façade of the Muzier Literature Museum.

Officer, engineer and experimental psychologist

Muzier was born on 6 November 1880 to a wealthy, upper-class civic family in the present-day city of Klagenfurt in the Austrian canton of Kehenten. At the time of his birth, Kernten was a principality of the Austro-Hungarian Empire under the Habsburg dynasty. His family belonged to a cultured middle-class public class, which enjoyed a high social status in the Habsburg dynasty after the nobility, and whose members often entered important positions in the country's military, administrative, cultural and educational fields through higher education. Muzier's father, Alfred Muzier, was an engineer and polytechnic professor who received the title of Counsellor of the Inner Court and was canonized as a nobleman after his retirement (shortly before the end of the Habsburg dynasty). His mother, Hermione, was the daughter of Franz Xavier Bergoor, one of Europe's rail pioneers. Other senior relatives, such as his uncle, held positions including officers in the General Staff, railroad engineers, and state court clerks. Muzir's early years of school followed the trajectory of this class and family tradition.

7-year-old Muzier.

In 1894, at the age of 13, Muzil was sent to the Military Secondary School of Merisch-Weiskiltszen in what is now the Czech Republic. Four years before him, another German-language poet who would later bring great fame to Austrian literature, Reiner Maria Rilke, also attended the school. Harsh militarized management and disregard for the emotional needs of individuals make the lives of these adolescents not good. Rilke dropped out of school early due to illness. As an adult, he wrote a short story called "Gymnastics Class" to subtly attack this military middle school education method, and some researchers believe that he has never been able to overcome the shadow of his military school life as a teenager. On the face of it, Muzier's situation was slightly different, as he successfully completed his studies at the Myrisch-Weiskiltszen Secondary School and in 1897 entered the Austro-Hungarian Military Technical Academy in Vienna as an alternate officer for further studies. However, his debut novel, The Confusion of the Student Torres, published in 1906, shows that this boarding life was also a period of confusion and pain for Muzier. The novel, which came to be considered a pre-rehearsal of the Nazi era, tells a brutal youth campus story of violence, bullying, sexuality and confusion, with the main characters and events based on real people and events from The Merish-Weiskierzen Secondary School.

Shortly after entering the Vienna Military Technical Academy, Muzir showed considerable talent in engineering and technology in ballistics courses, which prompted him to quickly adjust his career plan. In January 1898 he began studying mechanical engineering at the Deutsche Polytechnic University in Brno, and in 1901 he passed the state examination and became an engineer. The twenty years from 1890 to 1910 were a period of faith in progress and the "spirit of the modern machine", when European countries produced a number of technical officials, and the young Muzil had the ambition to become one of them. Like many of his novels, he advocates a calm, objective, rational and pragmatic engineer spirit. But it was also during this period that Muzier began to realize a fundamental ill of modern European spiritual life, namely, the severe separation of reason and emotion: on the one hand, the previous generation of engineers represented by his father reduced the needs of the mind and emotions to a sense of sentimentality that was useless, and on the other hand, the emotionalists rejected or even hostility to science and reason, and simply complained about the loss of the soul.

Muzier in his youth.

Perhaps it was at this time that the idea of trying to unify "precision and mind" was already taking shape in the mind of the young Muzier. In his view, the value of mathematical, physical and mechanical technical knowledge lies not mainly in the transformation of nature, but in the renewal of man's way of thinking and emotion, thus creating a new kind of man. Like Ulrich, who later wrote about him, he "loved science not from the point of view of science, but from the point of view of human nature", and the spheres of mind, emotion, and morality were his real concerns. Later, when he began to create "The Man Without Personality", this idea also profoundly influenced his writing style. Dissatisfied with his contemporaries' "too irrationality in the question of the mind," he sought to rationally and precisely observe, depict, and dissect everything in his work: people, spiritual types, social phenomena, and the "ghosts" of historical events. The explanation for the difference in his writing style from other writers of his generation is precisely: "Because I am an engineer." ”

In 1903, at the age of 22, Muzier gave up his position as an academic assistant at the Technical University of Stuttgart and went to Berlin, the holy land of art and science at that time, with a desire to blend scientific reason and spiritual emotion, and enrolled at friedrich Wilhelm University (now Humboldt University), majoring in philosophy and psychology, with a minor in mathematics and physics. Psychology was still a relatively young emerging discipline at the time, and Muzier's choice of specialization was probably influenced by the work of the Austrian philosopher Ernst Mach, whose advocacy of psychophysical monism undoubtedly fit his interest in blending natural science with psychic emotions. This study in Berlin also left traces in his later works, such as the description of sound perception in the short story "The Squid", the discussion of color in "The Man Without Personality", etc., which were obviously influenced by the experimental psychological research of his mentor, philosopher and psychologist Carl Stonepf.

The path of literature, war and escape from middle-class life

Along with his career path as an engineer and experimental psychologist, another trajectory in Muzier's life is developing in parallel: literature. Like most sensitive and thoughtful adolescents, Muzier wrote poetry as a teenager and, in his mid-twenties, published several short literary practices in Brno newspapers. However, without The Confusion of The Student Torres, the literary path of his life might have become deserted and eventually disappeared, as most people do.

The Confusion of Student Torres, by Robert Muzier Translator: Luo Wei, Edition: 99 Reader People's Literature Publishing House, September 2012.

Torres began writing Muzier around 1902 as an academic assistant at the Stuttgart Polytechnic University, and was published in 1906 with the praise of two heavyweight critics of the time, Alfred Kyle and Franz Blythe, with great success. Muzier had oscillated between his academic path and his status as a freelance writer, and the success of this debut led him to turn down an experimental psychology assistant position in Graz after his PhD and concentrate on literature.

More than thirty years later, Muzier, who had already completed most of his life's journey, wrote in a diary: "At that time, I had no idea how dangerous it was in life not to make full use of my opportunities. "But no one can foresee the future. At that time, Muzier may have thought that although the career of a freelance writer was not stable and certain, he still had the property of his parents to rely on, but he did not know that in just a few years, everything in his life would change dramatically.

Muzier's 1913 letter to Franz Blythe. The latter was a close friend of Kafka's.

The success of Torres did not last, and the response to the two short works created after this was mediocre. In 1910, Muzier, who had reached the age of independence but was still not financially independent, returned to Austria, and through his father's introduction, he found a position as a librarian at the Vienna Polytechnic University, and married his wife Marta Muzier the following year. However, both the tedious work of a librarian and the married life with Marta made Muzir feel forced and constrained. In 1913, he resigned from the library with a certificate of diagnosis of "severe cardiac neurosis." Shortly thereafter, he was offered a job at the Berlin-based Magazine Novén-Zeitung, where he was responsible for connecting with and helping some of the young expressionist writers of the time. He quickly set out for Berlin and joined the New Review in January 1914. Seven months later, world war I broke out, and he went to the Italian front as a reserve officer.

In fact, Muzier could have stayed in the rear, after all, he was unable to work as a librarian a year ago due to tachycardia and neurasthenia, but he chose to go to the front. An important reason was that he was deeply influenced by the mass fervor that pervaded the pre-war German and Austrian countries, and his article in support of the war in September 1914, "European, War, German", was indisputably proof.

Schiller paintings.

Years later, he described himself as if he had contracted a disease: "War is like a disease, or rather like the high fever that accompanies the disease, which has invaded me." But there may be another reason for Muzier's rise to the front, and that is a vague desire to escape the mediocre middle-class routine of a life of immutable work and marriage.

In fact, Muzier's previous choice of freelance writers, in addition to his literary ambitions, may have been partly due to an attempt to deviate from the conformist middle-class life of his parents' generation. Perhaps from his art-loving and somewhat neurotic mother, or perhaps from a long-dormant weariness of a peaceful life in the zeitgeist, there is an element of restlessness in Muzier's personality that prompts him to deviate from the established track of his family and class again and again. This impulse to deviate and derail is reflected in the debauched and chaotic days he spent in Brno around the age of twenty, in his repeated abandonment of career paths that would bring about a stable life, in his enthusiasm for war in the summer of 1914, in the mysterious runaway from home of the protagonist of "The Squid", and in the criminal impulses deep within Ulrich – another title of the third part of "The Man Without Personality", "Entering the Kingdom of the Millennium", is "Criminals".

The Post-War Years and The Man Without Personality

After joining the army, Muzil was mainly stationed on the Italian border of austria-Hungary, which was relatively calm at the beginning of the war, but also fought fiercely later. Muzil himself has had more than one encounter with death. As described in The Squid, the near-death experience acquired a certain mystique in him, an almost proud sense of selection and baptism. In April 1916, after a serious illness, he finally left the battlefield and took over the editing of the Tyrolean newspaper Les Soldiers. At the end of the war in 1918, Muzier worked for the Military Information Department in Vienna, and during this time the relevant documents he came into contact with played a great role in insight into the background of the war and the various social and economic relations of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire, and became an important intellectual resource for him to later depict the social background of "Kakânia".

At the end of world war I, the pre-war frenzy disappeared. Muzier wrote in his diary: "Five years of war enslavement stole the best period of my life. "But the impact of war goes far beyond that. In the early post-war period, living conditions in Vienna deteriorated dramatically, and the property of Muzier's parents and wife was greatly devalued and almost shrunk. Like many of his contemporaries, Muzier simply could not maintain a pre-war standard of living, and without the educator and socialite Eugenie Schwarzwald's rescue apparatus for poor artists and intellectuals, he and his wife might not have been able to survive the two famous "winters of hunger" in German-Austrian history of 1918 and 1919. During this time, publishing essays in newspapers was an important source of income for Muzir.

Schiller paintings.

The 1920s were the beginning of Muzier's economically difficult life and the period when his creativity was at its strongest. In order to make up for the enthusiasm interrupted by the war, he drew up a large number of writing plans, and published works such as the screenplay "Utopian" and the short story "Three Women". These works were recognized by critics, earning Muzier the Kleist Prize in 1923 and the Vienna Prize for Art in 1924. But despite this, the commercial success brought about by Torres before the war did not return. Muzier's highly anticipated play, The Dreamer, failed miserably after its publication, and according to Muzier's biographer Corino, the book sold fewer than 2,000 copies in seventeen years. To make ends meet, Muzier wrote numerous theatrical reviews for the Prague media during that time.

Three Women, by Robert Muzier Translator: Zhu Liuhua, Edition: Yilin Press, August 2013.

It was also during this time that Muzier began writing the most important work of his life, The Man Without Personality. The novel has several predecessors, and in addition to the 1920s Spies, The Rescuer, and Twin Sister, some of the characters in No date back even to 1903. Already then, Muzier had the idea of writing a "great novel." And when he regained that ambition after the war, he hoped that the novel would encompass all of his hitherto unfinished "philosophical and literary plans", including "at least a hundred characters" as "the main genre of contemporary man". However, as The Man Without Personality began to be written, Muzier also embarked on a painful journey for the second half of his life. In 1924, his parents died one after another. He then developed more and more physical, neurological, and emotional problems, and repeated writing blocks forced him to seek help from a psychiatrist. By this time he had hardly ever written theatre reviews, and he had no income other than the advance payments for novels provided by The Rovolt Press, which he had buried in his great works. In 1930, when Muzier was 50 years old, the first volume of "No" was finally completed after a delay, when he "could only survive for a few weeks at home."

"The Man Without Personality", by Robert Muzier Translator: Zhang Rongchang, Edition: Shanghai Translation Publishing House, August 2021.

In November 1931, in order to feel more directly the tensions and conflicts of german spiritual life, Muzier moved to Berlin again. During this time, as Rowhart Publishing House itself was involved in the whirlpool of economic crisis, the advance payment for "No" stopped. In 1932, Muzier, unable to make ends meet, was on the verge of suicide. Fortunately, the art historian Kurt Glaser and the banker Klaus Pincus organized an unofficial Muzier Society to provide the Muziers with the financial help they needed to make ends meet. In December 1932, the first part of the second volume of The Man Without Personality was completed. Just over a month later, Hitler came to power, followed by the May book burnings. Muzier and his Jewish wife were forced to leave Berlin and return to Vienna.

The last years of oblivion

Muzier 1935.

Whether during the Austro-Hungarian Empire or after World War I, Austrian German-speaking writers and artists relied heavily on the German cultural industry, with German publishing houses, newspapers and theatres being the biggest platforms for them to promote their work. Thus, after Hitler came to power, not only were the works of writers in Germany that did not conform to Nazi ideology banned on a large scale, but Also the German-speaking writers in Austria faced the same fate. In 1935, out of financial embarrassment, Muzier collected his short articles that he had previously published in the press and published them in a volume entitled "Living Legacy". This collection contains some outstanding satirical skits that are clearly critical of the situation. In a private letter, Muzier once said that he wanted to use the little book to send a signal that he would not be assimilated. Not surprisingly, Nazi Germany quickly caught the signal and soon banned the book in Germany. Under Nazi pressure, The Rowart Press had long since stopped promoting his other works. Since then, Muzier has gradually disappeared from public view.

"Living Legacy", by Robert Muzier Translator: Xu Chang, Version: Han fen Bookstore | The Commercial Press, February 2018.

In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria; in August, Muzier went into exile; in October, the Nazis banned The Man Without Personality throughout the German Empire; and in April 1940, all of Muzier's works were included in the "List of Harmful and Unpopular Works of the Third Reich of 1941." By this time Muzier had traveled to Geneva with his wife, but in the years in Switzerland he had not made any public comments or speeches, because if he came to the fore, he and his Jewish wife could be expelled by the declared neutral Swiss authorities. It can be said that in the last years of Muzier's life, on the war-torn European continent, almost no one remembers the existence of this writer.

It was in this state of complete oblivion that Muzier continued to work tirelessly according to his usual strict writing requirements. As a true perfectionist, he repeatedly revised proofs of the 20-chapter manuscript of The Man Without Personality, Part II, Volume II, retrieved from the publishing house before leaving Austria in 1938. Unlike the dominant brisk ironic tone of the first two novels, the third part of the novel, to which these 20 chapters belong, depicts a mysterious "other state" experienced by Ulrich and his sister Agath. A chapter entitled "The Breath of Summer," which he was revising on the day of his death, is considered by some critics to be one of the most beautiful texts in German literature.

In fact, for nearly a decade, from the end of 1932 until his death in 1942, the writing of The Man Without Personality was stagnant in the part where Ulrich spoke with Agat. Although economic hardship, health reasons, turbulent exiles, and sudden termination of life combined to make the greatest German novel of the twentieth century finally unfinished, Muzier's own personality, his strict requirements for "precision", is also a factor that leads to the slow progress of the work and even near stagnation, but it is this personality that gives The Man Without Personality an outstanding complex, deep and broad quality.

Muzier Literature Museum in Klagenfurt.