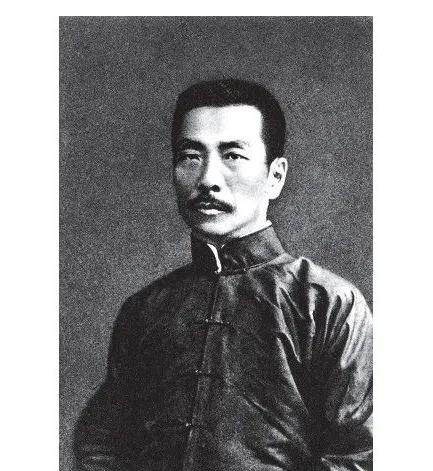

Photograph taken by Lu Xun for the Russian translation of A Q Zheng Biography (1925)

"A Q Zheng Biography" is a classic of modern Chinese literature. The image of Ah Q is thought-provoking, introspective, and places a profound criticism of China's national nature on Lu Xun. A hundred years later, it still has the charm of being read after reading.

The publication of Mr. Huang Qiaosheng's "Notes" tries to build a bridge of communication between Lu Xun and readers, not only respecting Lu Xun's original intention of creation, but also taking care of the current readers' reading feelings, in order to let today's public fully appreciate the meaning and charm of the literary classic "A Q Zheng biography".

Today, I share the afterword of "Notes" and understand this modern literary classic.

The idea of making notes for "A Q Zheng biography" (hereinafter referred to as "Zheng Chuan") has been haunting my mind for many years, and it was only done this year, which shows that I am not a good hand at notes. Notes, in the eyes of ordinary people, are far less than the writings, "Erya injects insects and fishes, and it is not a person who is not a man of the world", and the skill of gluttony is not enough to be called learned. However, the reason for my delay was precisely the fear that my trivial and chaotic knowledge would not be up to the task of annotating the Canon—i was sincerely afraid in the face of this literary classic.

Soon after the publication of "Zhengbiao", it attracted attention, and before the "Morning News Supplement" was serialized, some people speculated who the author was and who Ah Q alluded to. To this day, the work has been selected in whole or in part by secondary school and university textbooks, and has been translated into a variety of foreign languages. A hundred years later, it still has the charm of being read after reading.

At the beginning, I wanted to make a notepad, the content should be accurate, rigorous, vivid, interesting, needless to say; it is the form, but also want to take the classical (classical) way. Interesting to say, at that time, the classic image in my mind was actually traditional characters, thread binding, vertical arrangement, that is, the format of the Analects and Mencius annotations: Lu Xun's original text was in large characters, and the small characters of my notes were placed between the lines (double-line sandwich notes) or next to them (eyebrow batch), and printed on the fine rice paper. I even consulted with an alumnus who was quite well-written in italics to publish it by hand or photocopy — all in all, to give the classic the highest treatment.

2021 is the centenary of the publication of the "Zhengchuan" and the 140th anniversary of Lu Xun's birth, and the annotated version finally has the opportunity to be published.

When I started making notes, I had an idea of imagining the reader as a foreigner.

Foreigners are unfamiliar with Chinese culture and the reality of Lu Xun's era, and need the introduction of background knowledge and the interpretation of various famous objects. The reason I think so is that I think that some subtleties in the novel are difficult for foreign translations to convey. For example, in terms of currency value, "three hundred big money and nine two strings", the political term "persimmon oil party", etc., Lu Xun himself has explained to several foreign translators - including Chinese translators. For these words, foreign translators sometimes have to explain their special meaning in the form of footnotes and endnotes.

For example, in a more recent English translation, there is a translation of "persimmon oil party" as "Persimmon Oil Party", explained in a footnote: In Chinese, "Freedom", ziyou, sounds much like "persimmon oil", shiyou, an understandable error of hearing, therefore, by the good burghers of Weizhuang.(The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun , Julia Lovell, Penguin Books.) Even, translators sometimes put into the main text what should have been expressed in the form of footnotes or endnotes for the convenience of the reader, such as the reference to "Hong Ge" when the fake foreign devil recounts his revolutionary experience — the above English translation is my dear friend, and does not express the essence of the traditional Chinese Jieyi culture and Huidaomen culture contained in the word "brother" - followed by the following sentence: "By whom, his listeners may or may not." have been aware, he meant Li Yuanhong, one of the leaders of the Revolution.” The purpose is to let the reader better understand the political and social background of Chinese society at that time, and it is not difficult to understand with heart.

On other occasions, translators use paraphrasing to achieve better results by adding or subtracting the original text, such as "Brother Hong", a passage in a foreign language spoken by a fake foreign devil: "Let's do it!" He always says No! - This is a foreign language, you don't understand. Translated as: "'Let's strike now!' But he’d always say—here he broke into English —‘No!’ ... That’s a foreign word—you won’t understand.” Although the punctuation is somewhat complicated, the reader may not be able to figure out who the speaker is, but it is quite charming.

Gossip less, get back to business. It is doubtful whether a foreigner, no matter how connoisseur he is, can truly understand this "very Chinese" work. The literal problem is secondary, but more important is the understanding of cultural traditions and social customs. For example, Roman Roland read the "Canon" and said that the poor image of Ah Q left a deep impression on his mind, and he was particularly amused by the plot of Ah Q's chagrin that he could not draw a circle for the signature painting, which was his unique perception and some differences in the understanding of Chinese readers.

Although I assume that the target audience of the notes is foreigners, of course, the notes are mainly written to Chinese readers. What worries me more is that Chinese readers, because they are familiar with Lu Xun, do not have a sense of strangeness and novelty, but they cannot think carefully and deeply about the works. With a long-term immersion in the culture of the country, it is easy to take some things for granted. In fact, Lu Xun's purpose in writing this novel is to make readers think deeply and reflect. In this sense, I think it should be annotated in more detail, provide more references, and hope that readers can jump out of the circle, reflexively watch, and have some understanding. As for the so-called classics, different readers have different views, different perspectives will get different feelings, each reading will have new discoveries, and readers of different eras and different statuses will contribute new experiences.

Because of the long history and differences in customs, some scenes, sentences, classical and modern classics in the works (which have gradually become ancient), if not explained, even Chinese readers will inevitably have obstacles to understanding. The question is, to what extent is it better to note? There is a school of scholars who advocate "not seeking much understanding", believing that if you read a book a hundred times, you will be able to read your own experience. This is not unreasonable, and there are indeed people with such strong understanding. Moreover, I am really worried that too many annotated words will drown out the excitement of the original work, and it will not only be useless, but also annoying. Some people call "Zhengbiao" a miscellaneous cultural novel, with high cultural content and more discussion.

For example, the preface is almost a treatise on the title of a biography, which is itself a commentary on the title of the whole book. Then my note becomes a comment to the note. Or some people will think that this part of the original work can be unwanted, straight from the Zhao family prince Junxiu cai after Ah Q wants to surname Zhao, so that my notes have become an overlapping bed, the tail of the mink. Then again, reading these discussions and explanations about the title of the biography, readers can not only understand some literary and historical knowledge, but also understand Lu Xun's creative intentions from a deeper level.

The primary purpose of the note is to return to Lu Xun's original intention. Before and after Lu Xun published this work, the level of understanding and life experience changed. After the work was published, Lu Xun answered inquiries from the outside world and wrote explanations about the creative process, such as "The Causes of the True Biography of Ah Q", as well as the preface written for the foreign translation, as well as the text about the controversy of the work and the letters about the work with friends, etc., all revealed his creative intentions and ideological concepts, and played a programmatic guiding role in my notes.

The more important task of the note is to explain the ideological roots and psychological motivations of the actions of the characters in the work. Explaining the roots and motivations of Ah Q's various words and deeds, especially the connotations of his spiritual victory method, is not an easy task. In this regard, the annotated text occupies a lot of space in chapters such as "The Winning Strategy".

When I note, I pay more attention to the geographical, folklore, dialect and other words in the work. For example, the first chapter notes on "yellow wine" and the customs of atonement for sins in Shaoxing at that time; the second chapter introduces the method of "scooping rice" and "betting on the treasure" of the Shaoxing people in the old days; and the third chapter also provides some reference materials when explaining the Shaoxing local drama "The Tomb of the Little Lonely Widow" and asking Taoist priests to remove the ghosts.

Lu Xun sometimes spoke the Shaoxing dialect, but the average reader may not be able to see it. The notes refer to the research results of the academic community and make an introduction. For example, in the third chapter, Ah Q's action "Mo", Lu Xun originally planned to use the Shaoxing dialect to "squeeze", and the women in chapter six were afraid of seeing Ah Q and "drilled" everywhere.

Ancient words, of course, to explain, but the interpretation of the "present classic" is also very necessary, such as the Wuchang Uprising, fake foreign devils, the Liberal Party, etc., annotations help readers understand the background of the times and cultural atmosphere.

Reading such a rich classic work as "Zhengchuan", each reader has his own unique experience, which is the so-called "a thousand readers have a thousand A Q". My note is, of course, a hole and a bias, and I hope to be corrected by criticism. Commented on a pass, I have my own income. Because I systematically read Lu Xun's confessions and expositions on Ah Q, I realized that after the publication of the works, Lu Xun's thought has been further developed, the criticism of national nature has deepened, and the writing power is more focused and the style of writing is sharper in the later miscellaneous texts. I made an introduction in the notes, and at the same time I was deeply educated, and I felt that the shaping of the character of Ah Q did not seem to have been completed in Lu Xun's pen, and Ah Q's spirit had not yet reached its peak and was not fully developed enough. In the novel, Ah Q's successor is also Little D (Xiao Tong). If Ah Q had come to power — as Lu Xun later said in an interview, "They are still handling the state mile"— there would have been a lot of "datong" coming out.

Regarding the evaluation of the work, the opinions of several early critics are worthy of attention. Published in the Morning Post Supplement on March 19, 1922, Zhongmi (Zhou Zuoren's) "A Q Zheng Biography" captures the gist of the work in a few paragraphs. The commentators themselves later revealed that the article had been read to Lu Xun before it was published and had received approval. While praising, the article also pointed out some problems, such as the belief that Lu Xun's creative intention did not run through to the end: he originally wanted to push Down Ah Q, but in the end, instead of pushing him down, he was lifted up - Ah Q became the only lovely person in Weizhuang. I am very impressed by this note, it turns out that the image of Ah Q is not based on ugly feet, there are even uglier people around him. This reversal is chilling. The reader is proud, thinking that he is one or more than Ah Q, and when he reads the whole article, he suddenly realizes that he may be standing in the crowd watching ah Q's "reunion" ending. In this way, the reading results may also be a spiritual victory. Indeed, we should be wary: it is even more ridiculous and pathetic if we think that we have completely freed ourselves from the entanglement of ah Q's spirit and that the canon is outdated.

Classics are polished and must stand up to scrutiny. After the publication of the "Canon", comments poured in, some people said good, some people said bad. Lu Xun had read commentaries such as "Scream" by Xi Chen (Zheng Zhenduo) and "Reading "Scream" by Yan Bing (Mao Dun). Zheng Zhenduo pointed out that the novel Written by Ah Q's participation in the revolution caused a split in personality, which Lu Xun could not accept, and his defense was already reflected in the notes in this book. It was also suggested that in Chapter 9, the military and police of the brigade went into battle with light and heavy weapons to arrest a thief, which was really unnecessary and exaggerated. Lu Xun did not see it this way, and when he answered the question, he cited the actual events as evidence, and the notes in this book quoted the materials to briefly introduce the military and police system in China at that time. As for the factual errors, seasonal confusion, and inconsistencies in the "Canon", some Lu Xun himself later made corrections, and some researchers have pointed out that this note has been explained everywhere.

Due to the limitation of space, the annotations do not pay much attention to the evaluation of the gains and losses of the overall conception and narrative of the work, and the book does not append the historical commentary on the work. Now, with a little space, I will quote a few articles. Because positive praise has become common for readers, the emphasis on negative criticism here is in line with the creative intention of "exposing the shortcomings" of the "Canon".

On February 10, 1922, Novel Monthly, Vol. 13, No. 2, published a correspondence between Tan Guotang and Mao Dun on literary creation. Tan Guotang wrote: "The Morning Post has published four consecutive issues of "A Q Zheng Biography", and the author's pen is really sharp, but it seems to be too sharp, slightly hurting the truth. Irony is excessive, easy to flow into mannerism, making people feel unreal, but "A Q Zheng Biography" is not perfect. The creative world is really poor! Mao Dun replied with a different opinion: "As for Mr. Dengba Ren's "A Q Zheng Biography" published in the "Morning News Supplement", although it is only published in the fourth chapter, in my opinion, it is really a masterpiece. Your husband thought it was a satirical novel, but it was not the most important. Ah Q this person, to be realistically pointed out in the current society, is impossible, but when I read this novel, I always feel that Ah Q this person is very familiar, yes, he is the crystallization of Chinese character! As I read these four chapters, I couldn't help but think of The Russian Gongarov's Oblomov! ”

The year after the publication of the novel collection Scream, which contained the Main Biography, Cheng Fangwu published a review of the Scream in the Creation Quarterly, expressing disappointment and even contempt for the collection. He believes that Lu Xun's "early works have a common color, that is, the re-enactment of the account." Not only "Diary of a Madman", "Kong Yiji", "The Story of Hair", "A Q Zheng Biography", but also other articles are nothing more than some descriptions. The purpose of these accounts is almost entirely to build up typical characters; the author's efforts do not seem to be typical of the world he describes, but of the dwellers in this world. So this one by one is built, and the world in which they live is very vague. The reason why the world praises the author's success is because his typical building has been made, but it is here that I do not know the failure of the author. The author is too anxious, too anxious to reproduce his typical, and I think that if the author can not be so eager to pursue the 'typical', he can always find a little 'universal' (allgemein) out." He therefore denounced Lu Xun's novel art as "shallow" and "vulgar", judging that most of these works were "clumsy" and "failed". But in order to give Lu Xun a little "face", he rated one of the historical novels "Bu Zhou Shan" (later retitled "Patching Up the Heavens") as a good work with "some flaws". His critical essay does not deal much with the Canon, because, according to himself, he "did not even have the patience to read it when he criticized the A Q Canon." Nevertheless, he concluded that the Canon was a "shallow biography" and "extremely poorly structured."

Tianyong (Zhu Xiang) commented on the eight novels depicting rural life in "The Scream": "Although 'The True Biography of Ah Q' is the most famous, I think it is a bit self-conscious. And the person who portrays the squire's place to write "The History of Ru Lin" can also write it, although the paragraph that writes Mrs. Zhao asking Ah Q to buy a leather vest and the paragraph about Ah Q Dou Wang Hu can be the same as the description of the earth in "Hometown". (Table No. 6, Literary Weekly, October 27, 1924, No. 145) He also considers the first chapter of the Canon to be an imitation of don Quixote:

I have long said that "A Q Zheng Biography" in "The Scream" is not as good as "Hometown", and now I have found one more piece of evidence. The first chapter of don Quixote's novel opens with an argument about the real surname of the protagonist. The book says: "Some say his surname is Quixana, and some say his surname is Quesada (there is much discussion about this). However, we can reasonably conclude that his surname is Quixana (that is, thin man). Later he said: "At the end he decided to call himself 'Don Quixote.'" Thus the author of this history of letters concluded that his real surname was Quixada, not Quesada, as other authors had asserted. Of course, this kind of "famous science" can be said to coincide, but Lu Xun's novel is also a Q word to spin back and forth, which is inevitably suspicious. And "A Q" is structurally a study of Don Quixote. So I still hold the old view: "The Biography of Ah Zheng Q" is nothing remarkable. ("On the Poems of Guo Junmoruo Again")

In April 1979, Qian Zhongshu answered a reporter's question about Lu Xun at a small symposium at the University of California, Berkeley: "Lu Xun's short stories are very well written, but he is only suitable for writing short-winded chapters of short breath," not for writing 'long breath' long-winded, such as A Q is too long, should be trimmed curtailed." (Crystal "Miscellaneous Notes on "Throwing Books" for Serving Money - Mr. Chung Shu of Two Times)

There are many more such opinions about reading feelings, and I will not quote them all.

The implementation of the annotated edition of the Canonical Notebook exceeded expectations. The Commercial Press publishes paperback editions, and Beijing United Publishing Company and ChongxianGuan publish traditional chinese character line editions. Paperback line loading, all are good system, simplified and traditional, smooth context. The dedication of my friends in the publishing industry to the centenary of the publication of this classic work has made me admire and encouraged.

The annotated version of the "Canon" was published by the Commercial Press, which is also fate. The first English edition of the book (and the earliest full translation into Spanish) was published by the Commercial Press. In April 1925, The Chinese-American Liang Sheqian wrote to Lu Xun proposing to translate the "Zhengchuan", and in June he sent the English translation to Lu Xun for review, and on the 20th of the same month, Lu Xun returned the translation. On November 30, 1926, Lu Xun, who was teaching at Xiamen University, received three sample books from the Commercial Press, and six more from Liang Sheqian on December 11. Lu Xun wrote to a friend at that time: "The English translation of the "True Biography of Ah Q" has been published, and the translation does not seem to be bad, but there are also a few small mistakes. He also sent several of these copies to friends, including Ayssie (Gustav Ike), a German teacher who taught in the philosophy department at the same school. This version is 32 open, hardcover on canvas, blue gilded, elegant and solemn. It is said that there is also a protective seal in addition to the hard shell.

Zhang Yiping wrote in "Essays Under the Window": "Mr. Lu Xun's "A Q Zheng Biography", the Commercial Press has an English translation of Liang Sheqian. Its book bread crust, draw a Q shape, pigtails barefoot, sitting there eating dry smoke. Smell for the German a certain king's handwriting. Once Mr. Lu Xun saw it, he smiled and said, "Ah Q is even more cunning than this, not so honest." Unfortunately, we have not seen this image of Ah Q so far, or Zhang Yiping's memory is wrong, or because the protective seal is easily separated from the book, very little has been preserved. A copy that Lu Xun gave to Ai Chenfeng, which Ai shi gave to a friend, is now in the collection of the Lu Xun Memorial Hall in Shanghai — but there is no protective seal with the image of Ah Q painted by "Deren Moujun".

It is not easy to paint a portrait of Ah Q. Soon after the publication of the Canon, painters experimented with portraits. Some Lu Xun saw it and commented on it. After Lu Xun's death, Ah Q's portrait became more prosperous and became a grand view, and many long continuous drawings appeared. This book attempts to arrange the works of several painters in a comparative arrangement, not only to show the richness and variety of A Q's statues, but also to understand the differences between the various families: not only divided into north and south, but also Chinese and foreign, not to mention the difference in professional and technical skills such as sketching comics and Chinese prints. The framing and perspective are different, but each has its own good field, and the characters and scenes such as "dragon and tiger fighting", "courtship", "trial", "shooting", etc., have emerged with new meanings through the painter's sketch rendering, and once compared, they are more interesting.

The above text is excerpted from the "Notes"

Notes on the "A Q Biography"

Lu Xun by Huang Qiaosheng Notes

Mr. Huang Qiaosheng, an expert in Lu Xun research

Interpretation of the classic chinese modern literature "The True Biography of Ah Q"