Sunset shore

【Editor's Note】

George Floyd, a black man in The U.S. State of Minnes, was crushed to death by a white police officer, triggering protests in at least 140 cities across the country, with a few violent protests. In the wake of the two-week protests, a complex set of topics has been widely discussed. On July 4, in the fourth issue of the online series of salons on "Racial Issues and Torn American Society" sponsored by the New York Cultural Salon and the Bay Area Cultural Salon, Sunset Shore, a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology of the University of Pennsylvania, combed the historical context of the black movement in the United States with the title of "Race and the Territory of Social Movements in the United States". The lecture is divided into three parts, the first part of which mainly discusses why the history of specific social resistance and state violence has been diluted or even erased, and the challenge and transcendence of the black power movement to the ideology of the civil rights movement after the decline of the civil rights movement. The second is the issue of race in the Left Movement in the United States, and how the racial and class contradictions exacerbated by immigrants have continued to tear apart the American tradition of radicalism over the past hundred years. Finally, enter this wave of "Black Lives Matter" movements, which can glimpse the legacy of the historical black movement from its characteristics.

Sunset Bank authorized the text of the lecture to be published by The Paper for readers' enjoyment.

Public memory of social movements and black liberation

When people talk about social movements today, they are not just talking about the movement itself, but they are shaping a historical perspective, a way of understanding and remembering the movement after the fact. All social movements are filtered by the media system and academic research at the same time, and the filtered facts are constantly evoked by the text of history as a public memory and political argument.

For example, the black power movement that emerged in the mid-1960s has not had much video record and academic research. The only full documentary is The Black Power MixTape by a Swedish television reporter, which records some fragmentary images related to the black power movement from 1967 to 1975, which was compiled into a film released in the United States ten years ago, but because there are many materials missing, some years or even no material at all, the whole perspective is not very comprehensive. But no American media outlet in the 1960s or 1970s was willing to cover the black power movement in depth, so even documentaries were done by foreigners. Moreover, at that time, the Swedish filming team was also blocked by many parties, criticized by the US government and media agencies for spreading negative energy, and could not see the progressive side of American society.

American society's memory of social movements is rigid and there is a strong racial bias. First of all, the history of social movements has a strong white-centrism. Much of the research has focused on white-dominated movements, such as the New Left movement. Similarly, Chinese translated editions of books are largely confined to the New Left movement. There is also a great deal of research that has focused on some of the movements during the civil rights movement, such as the sit-in protests against Sit-ins, which affected attitudes among white Southerners. This self-evident assumption is that the success of the black movement is determined by whites. In addition, white men dominate the historical narrative. The new left's recollections and discourses were monopolized by the white core players. As a sub-discipline of cross-sociology and political science, the study of social movements is also extremely divided into race and gender. Not to mention that tilly, Tarot, and McAdam, the three major contributors to theoretical research, are all white men, and that few women of color are active in this field, and if they engage in similar research, they will be regarded by the essentialist thinking of the academic community as merely studying race and women, rather than as scholars who study social movements in a broad sense. Ordinary social movement researchers rarely participate in the work of sports organizations themselves, and there is often a huge disconnect between research and social movement practice.

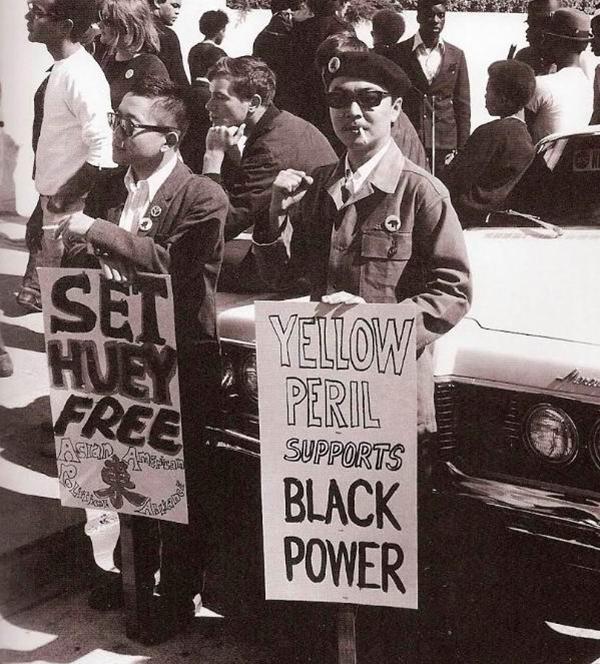

The first two factors are, of course, also subject to an important structural problem, namely, prejudice in the historical archives of social movements. White and milder black sports participants are better documented. Doug McAdam has this masterpiece called "Summer of Freedom", which tells the long-term impact of participating in the Summer of Freedom project on the lives of volunteers, and how they began to think about changing society and becoming more involved in politics in their future lives. But McAdam was able to write this almost groundbreaking book on social movements precisely because 90% of the volunteers in The Summer of Freedom were white, and then the archives were very complete. The data on black organizations, especially the radical black movement, is very fragmented, and much of it is in the hands of the FBI and the C.I.A., and even if the data is declassified, it will take years. The newly exposed story will also subvert people's perceptions, such as Richard Aoki, the only Japanese-American in the Black Panther Party at the top, and the East Asian man in the famous picture of Hello Peril supports black power, who was only exposed in 2012 as a long-term FBI informant, who successfully penetrated into multiple organizations and provided countless important intelligence to the US government.

The famous historical picture of yellow peril supports black power features Japanese-American Richard Aoki

Specific to the black liberation movement that began in the 1950s, its historical problems are more concentrated. I'll summarize five points here. The first is leader-centered memory and analysis, especially when it comes to articulating the divisions of the black movement, which brings together Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) and Malcolm Schwartz. X, it seems that everyone else's movement is a footnote to these two men. This problem exists even when talking about other organizations, such as the Black Panther Party, which thinks of Huey Newton and pays less attention to the contributions of other members, especially female members.

The second problem is that state repression has been heavily downplayed. The most typical example is the FBI's COunter INTELligence PROgram, or COINTELPRO, which broke the law under Hoover in the 1950s and 1970s. The project tracks organizations large and small in the civil rights movement, the New Left, the black power movement, and the radical left. The FBI also directly orchestrated the assassination of Black Panther Party rising star Fred Hampton and his bodyguard Mark Clark. Hampton, who was only 21 years old at the time, organized a very promising inter-ethnic coalition, the Rainbow Coalition, inviting radical groups of all ethnicities to join. The official refusal to admit the murder was also one of the main reasons for the dissolution of the Black Panther Party. In addition to the violent crackdown, the authorities also cracked down on the black movement by forging communications and other means, such as they would write letters to insult the Black Panther Party in disguise as members of other organizations, provoke distrust between organizations, or hype someone to be an FBI or CIA informant, a tactic also known as Bad-jacketing. The FBI's COINELPRO program is known because in 1971 eight actors infiltrated the FBI's regional offices in Pennsylvania and stole more than a thousand documents, and these activists later published them all to the major media and Congress, or else the relevant information would be released decades later. Today, although the FBI's surveillance and repression are constrained to some extent, they still have special surveillance programs for black radicals, such as the 2017 leaked text price shows that the FBI regards "black lives" as part of the "Black Identity Extremism" movement, but this movement is completely invented by them.

In mainstream discourse, black radicalism has always been considered violent, separatist, and socially divisive. Even supporters of the civil rights movement tend to hold such positions. White New Leftists such as Todd Gitlin have long claimed that black radicals have ruined the gains of the civil rights movement's reforms of ethnic unity. They also argue that black radicals betrayed the civil rights movement, leading to the rise of conservatism and cultural warfare for generations of 70 years. But in fact, if you really look at the history of the 1960s and 70s, you will find that the movement of the 1960s did not necessarily bridge the social differences at that time, and the picture of those black and white people fighting side by side had a lot of romantic elements, and the black radicals who were considered separatists did a lot of work of ethnic unity after the 70s.

The participation of women, especially women at the bottom, has been downplayed in the history of the black movement. For example, there are far fewer people who know Claudette Colvin than Rosa Parks, even though the former was the first to refuse to give up a seat to a white man. Because Parks was more in line with the stereotype of the protesters than Colvin, she was a married garment worker and worked in the local NAACP, so the NAACP intended to make her a leader at the time. But Colvin was a 15-year-old single black woman who became pregnant shortly after giving up her seat, her body was stigmatized by society, and no activist in the black community at that time was willing to publicize her story. In addition, Angela Davis has also mentioned on many different occasions that the struggle of countless ordinary black women has created MLK, such as the Montgomery bus boycott initiated by the black women's organization at the beginning, and the bus was also a large number of black women workers in the service industry who needed to commute, but later historical narratives emphasized more on the organizational work of MLK and others who intervened afterwards, and MLK became the core figure of the civil rights movement. Sociologist Belinda Robnett's research also revealed that most black organizations and black churches during the civil rights movement generally excluded women from core leadership positions, and black women were promoted to the middle at best. Therefore, the exclusion within the organization stimulates them to do more coordination, liaison, and education work, and becomes a node linking different communities. Ella Baker, the founder of the Student Nonviolence Coordination Committee at the time, was a good example of this, who did a lot of behind-the-scenes work on the movement, including unearthing and nurturing the next generation of actors. Deeply disgusted with Chrisma's leadership qualities, her more pro-grassroots style has also placed her on the margins of the civil rights movement's memory.

The final issue is the American-centrism that the United States is very good at on any topic. With the exception of the Vietnam War, historical narratives rarely place the United States in the context of global movements and the Cold War. After entering the 21st century, there are many more discussions in this regard, but in general they are still very insufficient, and many of the existing discourses are more romantic than Third World Romanticism, and there is not much analysis of the game between the more complex political movements of internationalism in the 1960s and 70s.

The American discourse of the sixties is often placed in a simplified "Good Sixties/Bad Sixties" dichotomy, which means that the first half of the sixties was good, the movement was non-violent, carried out within the institutional framework, and achieved some civil rights progress. By the rise of the black power movement in the late sixties, everything was directed toward riots and riots. There is also a lot of writing about how this dichotomy memory was solidified in the sixties. The first, called Framing the Sixties, looks at how politicians from both parties evoke memories of the 60s to serve their own party agendas from a party politics perspective. Another book, The Bad Sixties, analyzed the video works of the 1980s and 1990s, and found that the mainstream cultural community effectively dissolved the politics of the black movement by highlighting good sixties and various white subcultural products. One might admire the Black Panthers' attire and think they've created a fashion trend while opposing the ideology of black self-determination behind them. Another book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History, reflects on how American society has shirked the historical burden of slavery and apartheid by commemorating the civil rights movement. The civil rights movement was described as a kind of self-purification and redemption of American society, paving the way for the politics of Colorbindness that followed.

The rise and legacy of the black power movement

Although there was a black power trend during the civil rights movement, the rise of the black power movement as a whole was in the late 1960s, especially after 1968. Disappointment with the mainstream civil rights movement and the SNCC's efforts in electoral politics, from Malcolm S. The general despair sparked by the assassinations of X to MLK and Kennedy is a direct trigger. The Vietnam War also created an opportunity for the spread of black radicalism, because for the first time blacks, especially blacks who participated in the war, intuitively felt that their fate as oppressed people and the slaughtered Vietnamese were interconnected and isomorphic. Former SDS member Max Elbaum cited a survey in the Late 60s in the Air that showed that 30.6 percent of blacks who joined the military wanted to return to the United States to join a radical black group similar to the Black Panther Party.

One of the often overlooked backdrops in retrospect is that even in the early days of MLK's moderate stance, american society was a handful of people who supported him. In 1966, only 28% of Americans had a favorable opinion of MLK, indicating that the civil rights movement had absolutely no basis for public opinion at that time. At the end of May 1961, Gallup's investigation into the beginning of the interstate Freedom Riders movement was opposed to 60 percent of respondents. More telling is the contrast between public opinion before and after the March on Washington in 1963, when society became more resistant to the black movement after the black nonviolent march, arguing that nonviolent resistance hurt racial equality soared from 60 percent to 74 percent. The 1966 data showed the same trend, with 85 percent of whites feeling that the civil rights movement hurt blacks' quest for equality. Therefore, the assertion by many white New Lefts that American public opinion is conservative because of black power is untenable. The defenders of racial capitalism do not place more sympathy on a social movement and legitimacy. So it was the white supremacy that had always been very strong that drove the rise of black power, not the other way around.

Comparison of public opinion before March on Washington in 1963 and half a year later.

It is generally believed that the earliest black power organization was the Rebel Action Movement (RAM), although there was no concept of Black Power at the time, but this organization has always emphasized the liberation of black people around the world since the beginning of the development of black colleges and universities, and it has also been exposed to Maoism and Leninism earlier than the Black Panther Party. Because the RAM was active at the height of the civil rights movement, they had been working semi-underground to avoid state repression, which led to the fact that although the organization was actually very large and had many branches, very little data remained, many of which were from the archives of the CIA and the FBI. For example, CIA data from the 1960s, published under the Freedom of Information Act, showed that they were officially considered the most dangerous organizations of the time. RAM also inspired the creation of Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party, the former of which was a member of RAM before the Islamic State.

The concept of black power was introduced by Stokely Carmichael, who shouted the slogan at a Mississippi rally in the March Against Fear in 1966. In his early years he was also a moderate pro-civil rights movement, participated in the Freedom Riders movement, was influenced by the aforementioned Ella Baker, and led the SNCC, but by the mid-1960s he had largely lost any illusions about the course of the civil rights movement. After Stokely shouted the slogan of black power, most civil rights leaders panicked. Roy Wilkins, then chairman of NAACP, directly said it was "the father of hate and the mother of violence", and MLK also considered the slogan "unfortunate", which Stokely retracted, which was sternly rejected by the latter. In addition to the changing factors of the times, this line divergence is also largely an intergenerational problem. Stokely was born in 1941 and MLK was in 1929, a teenager, so Stokely responded by saying that I respect Dr. King, but we young people don't have his patience. Stokely and him had some strategic cooperation before MLK's assassination, but Stokely never compromised on his position.

The 1967 Stokely speech mentioned in the CIA's declassified archives comes from: https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP83B00823R000800050002-3.pdf

MLK and Malcolm X is different, and the disagreement between the civil rights movement and the black power movement is often reduced to whether or not to accept violence. But the more fundamental difference is in the way blacks were viewed, whether they demanded that the white state empower itself and legal status, or whether it seized and defined freedom itself. One of Malcolm X's most famous words is "Nobody can give you freedom." At the same time, the black power movement should be seen as a web-like, diffuse structure with many different factions within it. Some organizations support black separatism and independent nation-building, others believe in revolutionary socialism, and some organizations, like the Nation of Islam, are religious and do not reject capitalism, for example, they will support black entrepreneurs to start their own businesses. But the black power movement is still left-wing in its overall context, and there are some common characteristics that can distinguish it from the civil rights movement.

First, black power greatly broadened the scope of the civil rights movement. Because civil rights are relatively free and narrow concepts, the latter also includes equality in a series of aspects such as economy, education, health care, housing and so on. A very typical example is the Black Panther Party's 1966 draft of the ten-point program, which deals with issues such as free health care, education, affordable housing, and black exemption from military service, and they have been practicing various community medical education policing programs when they are well funded. This radical community practice is not only an internal pilot, but also inspires radical groups of other ethnic groups, such as the other Asian-American radical group in New York, I Wor Kuen (IWK, Boxer Boxer), which has a 12-point program, and their program is more gender-conscious than that of the Black Panther Party, and may be the most explicit anti-male chauvinism among all radical organizations in the United States.

The full text of the 12-point project of the Asian-American radical group IWK in New York is from: https://asianamericanactivism.tumblr.com/post/68946140266/i-wor-kuen-12-point-platform-and-program-i-wor

The second fundamental divide between civil and black rights is similar to much of the controversy over immigration, namely whether immigrants in the United States need to gradually integrate into white society or maintain their lifestyles and politics. The issue of self-determination and independence was further discussed by black power while retaining its own ethnic and cultural politics. A typical pro-black self-determination militant group was the New African Republic (RNA), founded in Detroit in 1968, which wanted five southern states with high black populations, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, to establish independent states, demanding from the United States $10,000 in slavery compensation per black person, equivalent to the unfulfilled promises made to blacks during the Reconstruction of the United States, and asking blacks to vote for themselves whether to join the new country. The RNA project was made to Atlanta, and Robert F. Williams, a black activist in exile in China at the time, was elected interim president, and the flag was modeled after the American design but adopted pan-African red, black, and green colors. These programs sound inconceivable now, but at that time such a trend of thought was definitely not without social roots. RNA's early years of national media attention were high, and the group survived political repression until the 1990s. There has been very little research on RNA, and the only book is political scientist Christian Davenport's How Social Movements Die, which analyzes the gradual decline of RNA before state repression and internal factional division.

The land extent of the RNA project is derived from: https://christiandavenportphd.weebly.com/republic-of-new-africa.html

The third type of disagreement lies in the degree of internationalism. MLK itself would certainly say that the liberation of people around the world was important, but only the black power movement really made de facto organizational connections. The story of the Black Panther Party in Algeria is a highlight of this history, and the most complete narrative of it is currently derived from the book Algiers, Third World Capital. Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther's information minister, fled trial and went into exile in Algeria in the late 1960s, initially welcomed by the new government to form a branch that also provided office space. Although the BPP has only one branch overseas, they do a lot of international liaison work through Algeria, and he has long been funded by the North Vietnamese government. But over time, the Development of the Panther Party's branch and the Algerian government have led to many clashes of ideas and funds, with the latter always hoping to incorporate the former into its top-down management system and twice confiscating large sums of money from overseas to the Panther Party. Therefore, from this case, we can also see that on the one hand, the international perspective of the black power movement is much broader than that of the civil rights movement, but on the other hand, many international connections are embedded in the national liberation structure of the world at that time and the suppression of the black movement in the United States, and the rise and fall of this external condition is still very critical.

The Black Panther Party newspaper reported on the Algerian branch from: https://twitter.com/SanaSaeed/status/1279926765150928896

Pan-Africanism, which provided an international context for the black power movement, had three important points in time. In a broad sense, the Haitian revolution at the end of the 18th century took on pan-Africanist overtones. At that time, the Haitian rebel army even had a transatlantic unity with the ordinary citizens of France during the Revolution. This is described in great detail in CLR James's early book, The Black Jacobin. The modern Pan-African movement probably emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when radical currents spread rapidly around the world, from anarchism to communism. During the same period, black radicals established many transnational organizations dedicated to the liberation of African Americans around the world. Although transportation was not as convenient as it is now, the modern visa regime had not yet been established, as in the United States, which was issued in 1924 with the Johnson–Reed Act, which restricted Asian immigration, so it was somewhat easier for activists to migrate and exile across borders. Benedict Anderson also mentions in The Age of Globalization the so-called early globalization features of the time, with the telegraph, the Universal Postal Union, steamships and railroad construction all conducive to transnational population movement. By the 1960s, with the independence movement of Asian, African and Latin American countries, the existing pan-African trend of thought coincided with the black power movement, so many figures in the black power movement later participated in the pan-African movement, including Stokely himself, who even changed his name to Kwame Ture to commemorate the pan-African movement.

Jamaican Marcus Garvey was a very important figure in the early years of the Pan-African movement, founding the first Pan-African movement organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL), and when he immigrated to the United States, he established a branch in Haarlem, New York. There is a very famous black activist bookstore in Oakland, California called Marcus Book, which is named after Marcus Garvey, and this time BLM protested that their bookstore also received a lot of donations. Another important organization was the All-African People's Revolutionary Party, founded in 1968 by Ghanaian exile Nkrumah, and later the U.S. branch in 1972, for which Stokely was in charge of it since he fled to Africa in 1969. Therefore, the international connections of the social movement do not necessarily radiate from Europe and the United States to the world, many of which are initiated in other regions and then spread to the United States through international migration, and this marginal to central model pays less attention to people.

Many of the Pan-African movements were born in the Caribbean, and Stokely was born in Trinidad and Tobago. The interaction between Caribbean actors and American social movements predates the civil rights movement era. For example, in the early 20th century, there were many radical anarchists in the Caribbean who established and participated in radical labor and ethnic liberation organizations in New York, and they also played a very important role in the Haarlem Renaissance. In addition to the earlier globalization trends mentioned earlier, historian Winston James' Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia analyzes another very important reason, that is, black immigrants in the Caribbean and the West Indies have a higher average education and class consciousness than blacks in the United States, and they do not feel apartheid deeply before immigrating to the United States. After these people came into contact with whites in the United States, they began to have a sense of blackness, but at the same time they were more willing to cooperate with white radical labor activists than local black activists. That is to say, the black radicals in the Caribbean, from Marcus Garvey to CLR James, became a bridge between white radicals and black radicals in the United States, integrating racial and class issues into the politics of liberation. This is crucial, and I will explain it further later when I talk about the racial issues of the left movement.

Although many of the black power organizations mentioned above no longer exist, their former members and descendants are often still active on the front lines of the social movement or offer their views on the current movement. Many people have also started non-governmental organizations. Therefore, the movements of various cities today can often carry the characteristics of the sports of that year. For example, Emory Douglas visited the SRA site in Mexico a few years ago to talk to the actors about the relationship between art and political action, and the result of their dialogue was the publication of the book Zapantera Negra.

The ideologies within the black power movement are diverse and complex. Organizations such as the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and the New African Republic have received most of the media attention, but there are many smaller organizations. In Philadelphia, the city where I live, there is a very famous black radical organization MOV. Founded in 1972, MOVE, in addition to the program of black self-determination and liberation, has a strong green anarchist color, more opposed to industrialization, and some historians believe that they were influenced by the Rastafari Movement in Jamaica. The organization was originally very low-key, buying a row of buildings west of Philadelphia and organizing its members to live in the style of an autonomous commune. But in 1978, during a standoff with the Philadelphia police, a policeman was shot in the back of the neck and killed. For this reason, Philadelphia police insisted that the MOV side fired the gun, and MOVE said that their guns were all bad and could not be misfired, and that other police officers shot the dead. Officials didn't give MOVE much of a defense, sentencing nine people to murder, most of whom were sentenced to more than 40 years in prison, and the media called them MOV9. The current men have either died in prison or have only been released after 2018, the latest development is that delbert Africa, a member sentenced to 42 years, was released only in January this year and died of cancer in June.

In 1985, WHEN MOV and the police clashed again, because the police could not get the members to leave the residence, they simply sent a helicopter to throw a bomb at THE RESIDENCE of THE MOVE, which caused a fire at the scene, killing 6 main MOVe members and 5 minors, and damaged more than 60 houses. The 2013 documentary Let The Fire Burn is about the clash between MOVE and the police, and the title suggests that when the police realized that the house was on fire, they deliberately asked the fire truck not to carry out rescue, waiting for the fire to devour the MOV members. No police officer was tried in the final massacre. This tragedy led to the basic destruction of MOV on the one hand, and on the other hand, it also stimulated the continuation of black power ideas in Philadelphia.

Smoke from the 1985 MOV explosion, from: https://thephiladelphiacitizen.org/the-lingering-trauma-of-move/

Any social movement of the 1960s and 70s was tainted with sexism. Black feminist artist Michele Wallace wrote a controversial book that was black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman because it was the first book to expose gender oppression within the black power movement. She argues that the misogynistic plot of the black power movement is reflected in the fact that the movement reinforces the image of noble warriors or elderly statesmans, either warriors or older speakers, all of which are very masculine. And many movement organizations themselves have been stressing the need to restore the dominance of black men in society. This was actually a counterattack to a famous 1965 survey by Moynihan's The Negro Family, which argued that a quarter of the single-mother households within the black community had led to a vicious cycle of black people relying too much on the welfare system and falling into a vicious circle of economic and cultural backwardness. The report's author, Moynihan himself, actually wrote that systemic discrimination over slavery was responsible for the disintegration of black families, but the report was later completely misinterpreted as evidence that conservatives preached a "culture of poverty" among blacks. The black power movement responded to this stigmatization in an equally distorted way that sacrificed the autonomy of black women.

Sexism within the Black Panther Party is a good reflection of the problem. Elaine Brown, who wrote a memoir called A Taste of Power, was the head of the Black Panther Party in crisis in 1974-1977 and appointed her to take over because leader Huey P. Newton went into exile in Cuba to escape trial. By then, the influence of the Black Panther Party had faded, and one of its founders, Bob Seale, had resigned from the party due to internal differences, and the members of the organization had gone their separate ways, leaving fewer than 100 people. Elaine actually did a lot of organizational work in a very unfavorable situation, including expanding existing projects, enhancing cooperation with other organizations and politicians, and greatly extending the life of the Black Panther Party. But later, when looking back at the history of the Black Panther Party, people also tended to completely ignore the contributions of female members. In his memoirs, Brown directly points out that black women are considered irrelevant in the black power movement. Even women as leaders are thought to have hurt the black manhood and even the black race itself.

In addition to Elaine's memoirs, The Revolution Has Come is one of the more gender-conscious in the Black Panther Party's history books. Although 60% of the members of the Black Panther Party in their heyday were women, the gender division and discrimination in the headquarters and most of the branches were very serious, such as logistics liaison, teachers and newspapers, almost all of which were run by women, and only three people in the history of the main leadership were women, and they were promoted because of close relationships with male members. Early career promotion channels for women and men were completely separate. Centralization within the organization is also severe, and those who disagree with Newton are expelled. A very interesting phenomenon mentioned in this book is that in the later stages of the development of the organization, because the contributions of female members have been ignored for a long time, they are not considered key figures by the police who come to search for them, so in the long run, the men in the organization are arrested, and the women are finally able to fill the gap and enter the management. This is similar to the previously mentioned example of how black churches ostracize women and make them conveners at the community level, and it is how structural discrimination in society has shaped the unique political struggle patterns of female activists.

Of course, it is not that the black power movement is particularly anti-women, in fact, gender discrimination in the civil rights movement is actually more common and straightforward. When recruiting students for the Free Summer Program, a very important criterion for screening female participants is appearance. Later, when McAdam was doing research, he accidentally turned over the file of that year and found that the person in charge had been commenting on the appearance of female applicants when reviewing the applicant's information, and many people were refused to participate because of their appearance. These all constitute the background of the later feminist movement and the rise of black feminism.

Racial issues in the Left Movement in the United States

The racial issue of the left-wing movement in the United States has been talked about by many people recently, and it seems that the black movement pays more attention to race and less to class. This contradiction also arose in the CHAZ-occupied area of Seattle, which had just been cleared a few days ago, when white protesters wanted to graft in the agenda of a larger anti-neoliberal movement, but some blacks would feel that these issues would hinder the more pressing focus of black life and black liberation, although they generally recognized neoliberalism as a more fundamental undertones. This debate has always existed, such as the new republic's article "Do American Socialists Have a Race Problem" in late 2018, which uses the example of the American Social Democratic DSA, the largest left-wing radical organization in the United States, to describe the exclusion of people of color within American socialists. The article was very controversial at the time, as whites within the left rarely admitted to having problems with racism. Indeed, race and class have always been very intertwined, and in many cases even mutually exclusive issues in American politics, which is one reason why the overall political spectrum of the United States is relatively conservative compared to many advanced democracies.

Dubois famously concluded, "The negro question is the greatest test for American socialists." In many of his writings, he meticulously portrayed the racist tendencies of labor politics, and white laborers often believed that their labor rights were damaged because of the presence of blacks. In Histaken Identity, Published in 2018, Asad Haider of Viewpoint Magazine also concluded that ethnic solidarity among whites has always been higher than class solidarity among people of color in the United States.

Racism against blacks has long been the glue that binds other immigrants into the United States, and blacks are the common enemy of all new immigrants, and the logic of integrating into mainstream white society by discriminating against blacks has not changed for a hundred years. Frederick Douglas once analyzed the hatred of blacks by Irish immigrants, saying that The Irish were willing to stand with the proletarians of the world in their homeland, but were taught to hate blacks as soon as they arrived in the United States before they could become white. In The Reconstruction of The Negro in America, Dubois begins by mentioning two parallel labor movements in the United States from the influx of European immigrants in the early 19th century to the Civil War to the early 20th century: black laborers gaining legal recognition and later becoming the cause of the civil rights movement, and white immigrant laborers fighting for land and higher wages, which later evolved into many early segregation unions such as the AFL. The two movements occasionally have some unions, but in general they are conflicting. Because at different times, white immigrant laborers, including many low-level whites, believed that blacks had depressed wages and robbed them of their jobs.

There is now a lot of writing on how European immigrants became white, the earliest influential book was The Wages of Whiteness, published in 1991, and there have been many similar documents based on this line of thinking. These later documents, such as Working Toward Whiteness, will depict in greater detail how European immigrants in the United States, in addition to psychologically feeling that they were always superior to blacks, gradually whitened themselves in the United States, including how they tried to put themselves on an equal footing with local white laborers by joining unions that excluded blacks, Mexicans, and Asians, and separated themselves from blacks who could not afford to buy a house by buying property. On the other hand, various immigration laws in the United States, such as the Immigration Act of 1924, restricted the entry of immigrants from many countries, resulting in the need for more black laborers in the North to replace the jobs of previous immigrants. This has also made American society, especially many businesses, begin to compare the advantages and disadvantages of blacks and immigrant workers, so that they feel that "some immigrants are more equal than other immigrants and blacks."

In a previous lecture, Mr. You Tianlong mentioned that because of discrimination in the formal job market, Asians are often hired to be union thugs for white strikes. In fact, it was more common for blacks to be employed at the time, because black men, in addition to being paid as low wages as Asians, had always been considered stronger and more violent, and physically more tolerant of pain. In the early years of the 20th century, these desperate union thugs were hired by professional companies across states and transported by rail, so the cost of employment was further reduced. In addition, because of the exclusion of the vast majority of trade unions, black workers have a grudge against white unions, which also makes them participate in the counter-strike with some revenge. A typical example is the steel industry strike that swept the United States in 1919, where the vast majority of strike thugs were black, and the organizer side of the AFL happened to reject black members. So in the end, the strike turned into a battle between black and white laborers hired by the management, which was very effective in breaking the unity of labor. The strike was followed by a collapse of the entire steel industry labour movement, and only 15 years later did a new strike take place.

For a history of unions and racism in the United States, see also Mike Davis's classic Preisoners of the American Dream. One of his central points was that the historical racism of trade unions had made the American labor movement more conservative and bureaucratic than other continental countries, something that all left-wing thinkers had not anticipated. The bureaucratization of trade unions in the United States includes neglecting to train grassroots activists, excluding other left-wing organizations, reluctance to include female-dominated clerical positions and Southern agricultural workers with a color majority, and not cooperating with the civil rights movement.

One exception is the IWW, founded in Chicago in 1905, the World Federation of Industrial Workers. The IWW has always been mobilized across races, genders, and borders, also influenced by the anarchist trend of labor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which believed that workers all over the world, regardless of occupation, should be affiliated with the same union, so their credo was called "One Big Union". But this is definitely not the mainstream of the labor movement, the IWW even in its heyday only had 150,000 labor members, and at the same time, the AFL's large industry chapters, such as the steel industry, can have 300,000 to 400,000 people. The IWW's organization is still there, and it can be seen in some medium- and large-scale urban rallies and strikes. But beginning in the 1960s, the IWW became directly involved in the civil rights movement, and later became more of a social movement organization than a typical union. Moreover, the IWW allows workers to belong to other unions, so its management of its labor is also more loose. The History Department of the University of Washington has made an IWW database with a lot of valuable historical materials and visualizations that are recommended to everyone.

The early Communist Party of America constituted another exception in ethnic unity. In the early 20th century, the Communist Party of America actively mobilized black radicals. The most obvious example is that around 1920 there was a black secret society called African Blood Brotherhood, founded by Cyril Briggs, a journalist and publisher at the time (who was also a Caribbean immigrant), claude McKay, and Harry Haywood. People with socialist tendencies within this organization later cooperated a lot with the COMMUNIST Party of the United States, and eventually even directly became a branch of the CP. Harry Haywood is one of the most famous, having studied in the Soviet Union and meeting many people, including Ho Chi Minh. According to the organizational propaganda materials of the COMMUNIST Party in the early thirties, it can be seen that they have a distinct racial stance, supporting the self-determination of black people in the South, and are close to the RNA stance. Regrettably, however, the COMMUNIST PARTY had gradually weakened the discussion of racism since the late 1930s, and had expelled many black radicals on the grounds of spreading black secession and nationalism. It wasn't until 1959 that CPUSA officially abandoned the slogan of self-determination for black americans. They felt that as capitalism developed and deepened, white blacks would automatically unite. At that time, when the civil rights movement was in full swing, the Us Communist Party not only did not have the advantage of intervening in the black liberation movement, but the white leaders expelled Harry Haywood and a series of other black members. Basically from this point on, left-wing radical movements in the United States, at least from the point of view of the members of the organization, formed a pattern of racial differentiation, which is still the case today.

Black Self-Determination Propaganda Materials for the 1930s, source: https://wolfsonianfiulibrary.wordpress.com/2018/01/15/civil-rights-and-the-cpusa/

The history of the mainstream civil rights movement in the United States often describes the 70s as very bad, as if the social struggle has come to a complete standstill except for the conservatives led by Nixon who began to fight back, but this is completely inconsistent with the fact that the labor movement in the United States reached its peak in the mid-70s, and the arrival of this peak is inseparable from the black liberation movement. After the 1960s, with the rise of the black power movement, black radicals began to stand on their own. The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), a labor organization that developed at the Detroit Dodge Plant at the end of 1968, led a strike by its workers, the first strike since the civil rights movement to shut down the factory completely. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers, developed by DRUM, was the most important black militant group of the '70s, embroiled in almost all major strikes and mobilizing many white laborers. But at an organizational level, out of desperation for whites, these organizations only allow people of color to join. The League was also one of the first organizations to propose and raise money for rehabilitations, mobilizing white religious organizations to receive at least $200,000 in donations, so it should not be assumed that all whites instinctively reject the idea of black power movements. The National Black United Front was also founded in New York in the 1980s, and the group is still active today. Founded in Chicago in the late 1990s, the Black Radical Congress brought together many black activists, pan-Africans, and academics, including Angela Davis, who also tried to work more closely with radicals of other ethnic groups. So in fact, after the civil rights movement faded in the late 1960s, the black movement still made great progress. The key problem is that when blacks developed their own movement organizations, because the recorders of the history of the movement tended to be white, these efforts were less easily seen. Michael Dawson explains in great detail in Blacks in and out of the Left how blacks drifted away from the white left, and the white New Left has been reluctant to acknowledge the role of black power movements in ethnic liberation, and then over time black radicals have been marginalized.

Summed up, a series of reasons have collectively led to race and class tearing apart the radical movement in the United States. First of all, the historical legacy of European Marxist thought has led many leftists to believe that class struggle takes precedence and that race is only a reflection of class. Many left-wing organizations also did not read the works of black thinkers such as Du Bois and Fanon. The history of the Communist Party of The Republic of America can also be seen in the gradual departure of the core organization from the black movement in the midst of differentiation. Moreover, black radicals were subjected to widespread state violence and forced to go underground. Post-war suburbanization and residential segregation are also likely to be detrimental to left-wing politics, as the left relies heavily on face-to-face community mobilization, but residential segregation has led to a lack of mobilization of the left to lower blacks and difficulties in building inter-ethnic coalitions. These factors have had the long-term effect of white-black distrust, and the establishment of separate radical left-wing organizations between different ethnic groups has led to the increasing isolation of black radicals and their marginalization in mainstream politics.

So now, at least from the perspective of votes, liberal ideas basically dominate black politics in the United States, and The Obama year has also consolidated the illusion of many people, and so far black people are still very dependent on the Democratic Party. At the same time, because of the long-term crackdown, black radicals have been in a relatively marginal and semi-underground state, generally unable to openly recruit members like white organizations, and many communities have not registered as social organizations. But on the other hand, in recent years, the BLM movement has made it possible for the black movement to be re-radicalized, and the black activists involved in the movement generally do not think about racial liberation within the framework of bipartisan politics, and the core activists are overwhelmingly employed in other left-wing, labor, and LGBTQ organizations. For example, alicia Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrice Cullors, three black women who raised BLM slogans, have been active in various labor and immigration movements at the same time, and they have emphasized on different occasions that BLM crosses borders.

At present, the de facto apartheid of contemporary left-wing organizations in the United States is still very serious. Many members of the public also already have the stereotype that the left is white and are reluctant to associate with them more. Here are four white left-wing organizations that are more dominant and have different positions. To say that white organizations do not mean that these organizations do not have members of color, but that the proportion of non-white people is very low, and members of color within the organization often experience obvious discrimination. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is currently the nation's largest left-wing organization, with more than 70,000 paid members. It was once a relatively conservative organization, founded in the 1980s when many of the more radical groups disintegrated. It's also a long-standing problem with racism, and in the 1980s the DSA didn't support the presidential campaign of Jesse Jackson, a black democratic radical, which historians generally believe is the result of racism within the organization. In the past two years, with more new members within the organization, some divisions have more internal racist reflections. Socialist Alternative (SA) is a Trotskyist organization whose popularity in the United States was largely enhanced by Kshama Sawant, who was elected to the Seattle City Council, and Sawant currently serves on the City Council and actively supports and participates in the local Occupation movement. The Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) is largely a white Stalinist organization that often takes a more dogmatic stance, but their focus on Latin American politics is probably the strongest of any organization. Redneck Revolt (RR) is an interesting left-wing gun-owning organization. So it also helps break the stereotype that white people who own guns are all red state conservatives.

The current left-wing organizations, which are predominantly black, are also ideologically diverse. Black Socialists in America (BSA) is a black socialist organization that was only formed in 2018, in large part in response to the DSA's racial issues, of course, compared to the DSA, the BSA has a much less public activity, and its members appear anonymously. The Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement (RAM) is anarchist community that also has a ten-point program modeled after the Black Panther Party, which includes the abolition of the police force and prisons. So now there is a faction in the Defund the Police movement that really wants to abolish the police completely, and there is no need to deny and cut. Cooperation Jackson is a network of cooperatives founded by Jackson, Mississippi in 2014. The Huey P Newton Gun Club, as the name suggests, is a gun-loving organization named after the former leader of the Black Panther Party. In general, in the political map of the left in the United States, the black left will be more anarchist. Because blacks are certainly oppressed in mixed ethnic organizations that practice democratic centralism, and anarchist organizations are more decentralized and can more effectively avoid state surveillance and repression.

Black Liberation Movement with BLM2020

Party and BLM support from: https://news.yahoo.com/new-yahoo-news-you-gov-poll-support-for-black-lives-matter-doubles-as-most-americans-reject-trumps-protest-response-144241692.html

Finally, I would like to talk about some observations of the current black life at stake and their relationship to the history of the black movement mentioned earlier. Although the black life that has been going on for more than a month began with anti-police violence, it has now developed into more topics. While there may still be a lot of opposition on the Chinese network, on American soil, black lives have had the support of a majority of the population for the first time since its inception.

From the polls, the slogan of Black Lives Matter was completely unconformed when it was first proposed under Obama in 2012, which is the same fate of all black movements and even social movements in history. The high level of public support for social movements is often the result of participants constantly mobilizing, persuading, and creating leadership. Comparing the data from 2016 and this year, it can be seen that in 2016, only 27% of the US respondents surveyed by YouGov explicitly supported the movement, and this proportion has more than doubled this year. Of course, the problem here is that there is no neutral option this year, so many people may shift their attitude in the direction of support, but the number of people who are clearly opposed to the movement has also decreased a lot. Then it's interesting to note that the opinion of the centrist independent voters has changed the most, which means that the movement has mobilized most of the middle voters, but has not made the Republican voters change their opinions.

Judging from the ethnic support level summarized by Pew, in addition to the overall more supportive of the various ethnic groups, the change in the perception of Latinos is the most dramatic, directly from the more supportive than whites in 2016 to the current high support of 77%. The overall feeling is that this nationwide BLM has greatly promoted self-education and solidarity among minorities by placing the situation of blacks before other minorities and immigrants. There is no comparative data on Asians here, but a separate survey found that the decline in Asian perceptions of the police under protest was the most obvious. There has been a lot of debate lately about why Asians don't support the black movement, but for Latinos, it's just as difficult for many people to empathize with black people except for undocumented immigrants. During this protest, Latinos, especially white Latinos, also had anti-Blackness to reflect on themselves, and even how to effectively talk to parents and older generations. So in fact, Asians can also identify each other and creatively face the problem of racism within the community through association with Latinos.

2016 BLM Ethnic Support From: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/08/how-americans-view-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

The final chart shows the interaction of different demographic variables and political participation behavior in the same Pew survey, and you can see that the participation rate of Latinos and Asians is very close to that of blacks. Even in terms of donations to organizations, the proportion of Asians far exceeds that of other ethnic groups. According to the proportion of protest participation in the past month given in the chart on the right, only whites are dragging their feet, and Asian participation is the highest of all ethnic groups. We think Asian participation is low because the total number of Asians is really too small to see each other in protest. Of course, this kind of survey often only interviews Asians who speak English, so the actual proportion will be lower, but at least it shows that the enthusiasm of the younger generation for political participation is very high.

Pew Interaction of different demographic variables with BLM political participation behavior, Source: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/psdt_06-12-20_protests-00-10/

The high level of cross-racial support for the BLM movement is accompanied by its decentralized character. In my opinion, decentralization is specifically combined with three sub-characteristics, commercialization, urban community, and mass surveillance. But when social movements develop to a certain extent, there will be some commercial overtones, or more companies will see that public opinion is willing to support BLM's demands. In the early days, sports companies like Nike may have supported it, because there were many black people in the customer, but now Internet companies such as Amazon, Spotify, and Netflix have also joined the BLM front. Ironically, the Amazon is precisely the root cause of the continued poverty and oppression of blacks. The gentrification it has caused, the squeeze on its service workers, and the crackdown on the warehouse and WholeFoods strikes under Covid19 all illustrate the hypocrisy of its support for BLM. In 2018, Amazon was also revealed to sell one of its facial recognition software, Rekognition, to the police. Against this backdrop, there will certainly be strategic support for commercial companies within the BLM movement, as well as radicals who oppose the incorporation of capitalism. How to coordinate the position within this movement under a decentralized structure, rather than tug-of-war, is a challenge for the future movement.

This time, there were a large number of people on the streets in various places, and the slogans were also very uniform, but the potential and demands of the movement in each place were actually very different. Because the implementation of demands like Defund the Police is certainly a struggle and mediation between the participants in the movement and the local mayor, the city council, and the police department. Police department budgets are generally approved by the city council, such as the city council's approval two days ago to cut 7% of the NYPD's budget for the next fiscal year. The situation is also very different from place to place if there are racist statues and murals demolished, and some historical statues may be in other minority communities and universities, and there is also a need for coordination between protesters and community leaders, various social institutions.

Another factor in the center of the center is the different historical legacies of social movements in different cities, and I will give the example of Seattle and Philadelphia, where I live. The most special part of the Seattle protest this time is the CHAZ/CHOP occupation zone. This area was emptied a few days ago, but there are still valuable sports experiences and lessons to be learned. The success of Seattle in achieving occupation rather than simple marches has a lot to do with the decades-old occupation culture and the rise of anarchist communities. Since the 1970s, Indigenous and Latino communities have organized many occupations of wastelands and schools. In addition to the BLM people, there are also a large number of communities involved in Occupy, as well as some mutual aid organizations that have emerged under the epidemic. Because Occupy is predominantly white, there have always been racial and movement lines within the movement, such as whether the autonomy and occupation agendas would interfere with more pressing police reforms, disputes that did not ease until the end of the occupation. But overall, Seattle's history of ethnic solidarity has been very helpful to this movement.

Philadelphia's political ecology, by contrast, is very different. There is a very strong history of the black power movement, the first black power movement organization in the United States RAM was headquartered in Philadelphia, and other black power organizations also had branches in Philadelphia, and of course, MOV. In this BLM movement, the activists in West Philadelphia commemorated the thirty-fifth anniversary of the MOVE explosion and made a special short film, which shows that the social movement in Philadelphia is still strongly influenced by the history of that year, and the demands are much more radical than other places, such as the activists here who oppose the self-dwarfing slogan of "Hands up, don't shoot". While many of these protests do not attract national media attention, they have a great impact on local politics.

The final challenge is how to deal with mass surveillance. The black movement in the United States is subject to the tightest state surveillance. In this BLM demonstration everywhere, city and state police, National Guard, FBI and military have sent unmanned reconnaissance aircraft and patrol aircraft to monitor military level. The Department of Homeland Security and Customs Enforcement alone broadcast and recorded at least 270 hours of footage of protest crowds, not including archives from other local authorities. In the face of this kind of surveillance, I think american activists are still not doing enough, a lot of news and communication rely on public Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, but right-wing movements such as Boogaloo use encryption software more. The largest BLM channel on telegrams currently has fewer than ten thousand followers and is completely fragmented, which could hurt future movement coordination.

References:

Bothmer, Bernard von. 2010. Framing the Sixties: The Use and Abuse of a Decade from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush. First edition edition. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Brown, Elaine. 1993. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story. 1st Anchor Books ed edition. New York, NY: Anchor.

Davenport, Christian. 2014. How Social Movements Die: Repression and Demobilization of the Republic of New Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, Angela Y. 2016. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. 4TH PRINTING edition. edited by F. Barat. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.

Davis, Mike. 1999. Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class. Verso.

Dawson, Michael C. 2013. Blacks In and Out of the Left. Harvard University Press.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. 1998. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880. 12.2.1997 edition. New York, NY: Free Press.

Elbaum, Max. 2018. Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che. New edition. London: Verso.

Haider, Asad. 2018. Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump. London ; Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Hoerl, Kristen. 2018. The Bad Sixties: Hollywood Memories of the Counterculture, Antiwar, and Black Power Movements. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

James, C. L. R. 1989. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. 2 edition. New York: Vintage.

James, Winston. 1999. Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth Century America. Reprint, edition. London ; New York: Verso.

Leonard, Aaron J., and Conor A. Gallagher. 2018. A Threat of the First Magnitude: FBI Counterintelligence & Infiltration From the Communist Party to the Revolutionary Union - 1962-1974. London: Repeater.

McAdam, Doug. 1990. Freedom Summer. 1 edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mokhtefi, Elaine. 2018. Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers. Verso.

Robnett, Belinda. 1997. How Long? How Long?: African American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights. 1 edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Roediger, David R. 2005. Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs. New York: Basic Books.

Spencer, Robyn C. 2016. The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland. Reprint edition. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

Theoharis, Jeanne. 2018. A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Ture, Kwame, and Charles V. Hamilton. 1992. Black Power : The Politics of Liberation. New York: Vintage.

Wallace, Michele. 2015. Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman. Reprint edition. London: Verso.

Whatley, Warren C. 1993. “African-American Strikebreaking from the Civil War to the New Deal.” Social Science History 17(4):525–58.

Editor-in-Charge: Wu Qin

The Surging News shall not be reproduced without authorization. News Report: 4009-20-4009