Cashier Xiao Qiu

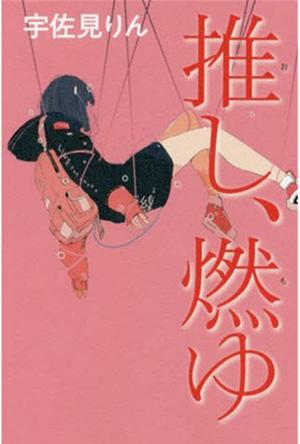

According to Japanese media reports, by the end of April, the sales of writer Usami's novel "I Push, Burn" ("Push, Burn") officially exceeded 480,000, and its translation in seven countries and regions around the world has been officially decided. Since the work won the 164th Ryunosuke Wasagawa Literature Prize on January 20 this year, it has received great attention in Japanese society. There are both anecdotes such as the author or a university undergraduate student who is the third youngest winner since the founding of the award, as well as the "traffic" that comes with the theme of the work— idols and star chasing. In fact, whether it is the "Chuang" and "Qing" two major drafts that have not yet faded in popularity, or the more daily "pink and black wars", the topic of idols and fans has become an increasingly concerned phenomenon in various countries, including China. From this point of view, both inside and outside the novel, the current situation of Japan, as the de facto founder of the "idol industry", and its star-chasing subculture have comparative significance across limited regions.

The flesh and spirit of the "fans"

"'I push' on the inflammatory. It is said that it hit the fans. ”

This is the beginning of the full text of "I Push, Burn". For people who are not very familiar with the culture of the rice circle, this first sentence probably contains half of the words that cannot be understood. The "Tui" in the rice circle comes directly from the Japanese word "Tui", which usually refers to the object that fans most support, whether it is an idol, an actor, an anime character or even an animal. The word can also be combined with other Kanji to describe different types of fans. For example, I like the "single push" of only one member of the group, and I like the "box push" of all members. The familiar "straight shot" of "Xiu Fan" is also "pushing " ( push + camera ) in Japanese. On the other hand, "Yanshang", which also comes directly from the Kanji in Japanese, is mainly used to describe idols and other words and deeds that have been criticized by society for their deviant words and deeds. In today's Internet age, the "fire-like" whipping of such public figures also comes mainly from virtual space. Although japanese idols are generally less influential in China than in the early days, these easy-to-understand and slightly "yygq" (yin and yang weird) terms that originated in the "Japanese circle" are still well known, localized and reused by other domestic rice circles to varying degrees.

Returning to the novel itself, after this exciting and suspenseful beginning, the story does not unfold according to the speculative novel-style routine of revealing the truth behind the "hot incident". Instead, the main content of the book is a depiction of the daily life of a specific fan of the accident idol "Makiri" (the original name of the protagonist is "あかり", and there is no Kanji correspondence). Here it is temporarily translated as the common "Mingli"). Akari, who is still a high school student, has always had problems with his body. Vomiting, cramping, and distracted attention are the constant torments she has experienced since she was a child. In the book, the author only mentions that her diagnosis book is lined with "two diseases", but many netizens speculate that the protagonist may be suffering from developmental disability ("gaiata disorder" in Japanese). The only thing that could bring a shred of relief to her troubled life was her "push" Ueno Masayuki. In fact, when he was very young, Akari had seen the stage plays of Makoto, who was still a child star at that time. But she really fell in love with Makoto on an afternoon when she was 16 years old and skipped class. Akari, who inadvertently re-watched the STAGE PLAY DVD, was suddenly attracted by The Luck of Playing Peter Pan in it. Since then, she has become a "single push" for Makoto, who is now a member of a mixed group of five men and women.

Young fans who have had similar experiences, especially young fans, may smile at the depiction of Mingli's star-chasing behavior in the novel: the idol's album must be bought: preservation, ornamental and "missionary" use; the idol's speech on TV, magazine or social networking sites will return to watch it and become familiar with it; although it is usually frugal, the "garbage goods" printed with idol photos will not be softly thrown at thousands of dollars... At the same time, Akari is also a small "powder head". She runs a dedicated blog about her "pushing" online with a lot of clicks. Akari actively updates the latest "material" on it and pairs it with his own "rainbow fart". And there is always a group of "loose fans" who will actively like and share their star-chasing experience.

The most distinctive or literary feature of "I Push, Burn" is its detailed depiction of Mingli's "flesh" and "spirit" in the process of chasing stars.

For Akari, his sick body has always been a burden. The book repeatedly describes how her hair and nails, etc., would grow long quickly even after trimming. This inevitable human metabolism seems to Akari like gravity that cannot be rejected. At the same time, her absent father, who went abroad, revealed from time to time an impatient mother, a generally gentle sister, and a primitive family network of grandmothers who eventually died became a shackle that she could not get rid of. This physical weight can only be liberated when you see your "pushing" true fortune. The "Peter Pan" played by Makoto when he was a child is not only always flying lightly in the air itself, but this image represents a "Neverland" that can never grow up, which may be the promised land of Akari who cannot face growth.

On the other hand, as many readers have pointed out, the relationship between Mingli and "push" in the novel is full of religious implications on a spiritual level. Akari's room is surrounded by layers of Makoto's "member color" blue, and every once in a while she has to take pictures of the newly created perimeter in the shape of an "altar" for photos. Akari also used to watch the constellation divination of the day when he went out every day. But what she cared about was never herself, but the luck of "pushing". At the end of the story, when Makoto was forced to quit the group and entertainment circle because of beating up fans, Akari couldn't help but sigh: "My 'push' has finally become a person." In the final scene of the much-discussed novel, the desperate Akari knocks over a box of cotton swabs. Critics generally believe that the protagonist who picks up all the white cotton swabs scattered in a ball is like picking up the last white bones of the deceased at a traditional funeral. But whether this goodbye to the flesh leads to spiritual despair or redemption, different readers may have different interpretations.

The sociology of fans

In addition to the solid language skills and the literary nature of abundant symbolism, if we read it from a sociological perspective, we can also find many interesting phenomena.

First of all, from the perspective of the society within the novel "I Push, Burn". The protagonist, Akari, is obviously building his social world through the core of the relationship between "pushing" and fans. Except for her innate family, all her friends are related to star chasing. Akari thinks that if he "takes off the powder" one day, the most reluctant thing is to "push" is the fans who actively reply to their blogs every time. They usually take the initiative to share their feelings of chasing stars, and after the "push" accident, they hug each other and comfort each other. In real life, Akari's only friend, Chengmei, also met because of the common language of star chasing, although the objects of their "push" are different. But the author's retention of this very thin network of people is not a single critical attitude. Borrowing from Mingli, the author asks, "Why do all social relations need to be reciprocal?" "This question. What Akari pursues is this unreponsive love between idols and fans. Isn't it nice to just look at idols and get power?

From another point of view, the idol also goes beyond the interpersonal circle around Akari and influences her connection with the whole society. One of the most important places in the book is the small restaurant where Akari works. The metrics she uses to measure the significance of part-time work are still closely related to "pushing": working in a restaurant for an hour can buy a "bio-writing" (referring to a copyrighted idol photo), two hours can buy a CD, and at the same time, a vote can help "push" to get a higher position in the next performance. The internal logic of the market and capital is not replaced by the relationship between "pushing" and fans, but is more handy under its cover. Similarly, this kind of star-chasing behavior that is easily seen by others as a bit crazy is not entirely negative in the book. About a quarter of Japanese high school students work part-time after class. Taken together, Akari's family is not very poor. It can be said that it is because she wants to get extra income to chase stars that she has the courage to get out of her comfort zone. Only in the end, her heavy flesh still did not allow herself to persevere.

From another point of view, we can also start from the inside of the novel to reach the entertainment world of the reality outside the book.

The only friend of the protagonist mentioned above, Chengmei, originally chased after a popular idol group. But when she "pushed" to graduate and went abroad, Cheng mei immediately turned to "push" an unknown underground idol. After exchanging money for familiarity, Chengmei finally succeeded in realizing her dream of "pushing" and "privately linking" with herself by plastic surgery. In reality, the explicit grading of the Japanese idol industry may be even more brutal than in the book. The "48 series" and "46 series" in the women's group and the Janis in the boy band can be said to be at the top of the pyramid. Downwards, the "local idols" defined by each region rely on greater affinity to share a piece of the pie with local capital. Finally, a variety of "underground idols" are emerging in an endless stream. They are like the part of an iceberg below the horizon: the largest volume but never seeing the light. These people are permanent in small clubs or bars, and often have occupations other than "idols" to subsidize their families. Many people choose to quit silently after years of perseverance but still can't realize their dreams. For others, under the exploitation of the company and the squeeze of the market, they should have been the spiritual sustenance of the fans, and they had to sell their flesh to survive.

In contrast, what about real-life fans? The "typicality" of the novel's image is an element that people often talk about when commenting. Although Mingli in "I Push, Burn" has a unique family birth and character personality, her star-chasing behavior can be said to be a microcosm of the majority of fans. At the same time, another dialectic of "special" and "universal" lurks in the changing popular culture of Japanese youth over the decades.

I believe many people know that in the 1990s and early 2000s, the "hot girl culture" (ギャル) was once popular among young Women in Japan. These young women, who are passionate about bright hair color, exaggerated jewelry and, most importantly, black rice dumpling complexions, are very easy to "stand out" from other groups. Although we can still find the remaining "hot girls" in specific coffee shops such as Shibuya today, the more important representatives of young women's culture have undoubtedly been replaced by the so-called "mass production type" in recent years. Most of the fans who go to idol concerts such as Janis dress very similarly: "steel bangs" that don't deform plus brown side rolls, pink blushes that focus on transparency, and dresses that are also pink and must have bows. In terms of accessories, because the fortress has a lot of its own "push" of the aid, "mass production" women will generally choose a functional large bag, but embellishment with "Melody", "Kulomi" and other Sanrio cartoon images can save some "women's power". Finally, in cyberspace, their most commonly used SNS tags are: #想和只推XX的量产型宅女联结. In other words, these young female fans are open to the seemingly pejorative term "mass production." Of course, under the framework of "mass production", there will be subdivisions such as "mine system" and "psychiatric system". Here's a slight divergence: the "psychiatric department" here comes from the Japanese "メンヘラ", which is basically the "Japanese System English" obtained by nounizing the English abbreviation of physical health plus the er suffix. Girls who use the term to describe themselves usually don't have a clinical presence except for some people who are actually as ill as Akira in the novel. It is more used to describe the combination of adding elements such as dark colors to the above-mentioned "mass production" makeup and clothing to make it appear more "dark", as well as personalities such as dependence and "sick petite" in interpersonal relationships.

As the Frankfurt School once mentioned in its critique of the capitalist mode of production, the fundamental reason for the emergence of these "mass-produced" girls is the fast-selling market that relies on large-scale media capital and its modular production principles. And the sub-classification below them is only similar to the different brands of shampoos under the same monopoly daily chemical manufacturer that seem to be competing (from a psychoanalytic point of view, "psychiatric department" is a topic worthy of further investigation). More importantly, of course, is the deep reason behind the "optimistic" acceptance of homogenization by these young female fans: the increasingly rigid social structure can no longer accommodate the space that can be so different from others.

Women and Literature Award

In the novel, we can once again find that the author has more than just critical emotions towards "mass production" fans. For the protagonist of the story, Akari, even the product of living on the assembly line already requires more effort than others. For young women in the wider reality, it is difficult to say that they actively accept the fact that they are "mass-produced" and self-deprecating it is not "the rebellion of the weak" in the context of the above social stereotypes. Their active embrace of these labels is a stressful response when they find themselves less special than they thought. Perhaps a more noteworthy point is the fact that the complexity of this young woman's identity and identity is not only being written by more and more female writers, but is also gradually being embraced by more traditional "literary circles".

In fact, in 2019, the relationship between women and literary prizes has been hotly discussed in Japanese society. In the shortlist for the Naoki Prize, announced in July of that year, all six candidates were women. This is the first time that the two major Japanese literary prizes, the Pure Literature Prize and the more entertaining Naoki Prize, have occurred since their creation before the war. According to the statistics of the Japanese media, the two awards, which are awarded twice a year, have a very uneven gender distribution among their winners. Taken together, the proportion of male winners can account for more than 70%. Although many women writers had become mainstream in the literary market before the war, it was not until the 8th Wasagawa Prize in 1938 and the 11th Naoki Prize in 1940 that women won for the first time.

The gender inequality in these literary fields did not begin to change until the 1980s of the last century. According to a commentary in the Sankei Shimbun, it was precisely with the increase in women's social participation that their status in literature increased. Indeed, Japan's Equal Employment Opportunities Act of 1986, which was enacted, legally gave the same guarantees to both sexes in the workplace. The following year, women were selected for the first time on the jury of two literary prizes. In 1996, for the first time, the winners of both awards were presented by two women at the same time. The report also quoted the literary critic Minako Saito as pointing out that in fact, at present, whether it is pure literature or entertainment literature, it is more or less facing the dilemma of being untitled. And if literature originally originated from "scars", it is not difficult to understand that women who are always facing systemic gender inequality have more inspiration and themes to write than men. Returning to "I Push, Burn", the author Usami's life experience does indeed conform to this hypothesis. Although Usami did not have the same illness as Akari, she also said in an interview that she had encountered physical and mental setbacks in her student days that made her want to drop out of school. At the same time, she still has her own "push" to this day. The actor's work has always brought her comfort.

But on the other hand, this idea that women can only write their own personal experiences is somewhat "essentialistic", so that it is still fundamentally suspected of denying women's creativity. This is reminiscent of another literary prize in Japan called the R-18 (meaning 'eighteen forbidden') literary prizes written by women for women. The award, created in 2002, aims to encourage women writers to create erotic literature. Since 2012, the organizers have removed restrictions on the subject of submissions on the grounds that women's writing "sex" is no longer rare. But at the same time, it also emphasizes the hope that the submission can show the ambiguous expression of "women's unique sensibility". As an encouragement to the winners, in addition to 300,000 yen in cash, the organizer will also come with a body fat measuring instrument. In order to achieve gender equality, should gender differences be emphasized or erased? Is "femininity" self-identification or stereotyping? These inconclusive controversies in the social sciences are equally inevitable in the field of literature.

Commenting on the "incident" of all female candidates for the 2019 Naoki Prize, Natsuo Kirino, a former winner of the award and one of the current selection committee members, said that the judges did not take gender into account in their selection, and this situation was completely "accidental". She added that "hopefully our society will one day not be surprised by similar results."

Editor-in-Charge: Fan Zhu

Proofreader: Yan Zhang